HESA Shahed 136

| Shahed 136 | |

|---|---|

A Shahed 136 at an exhibition | |

| Type | Loitering munition |

| Place of origin | |

| Service history | |

| Used by | |

| Wars | |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Shahed Aviation Industries |

| Manufacturer | Shahed Aviation Industries[1] |

| Unit cost | $193,000[2] (export; various estimates for domestic production cost range from $10,000 to $50,000)[3][4][5][6] |

| No. built | Unknown |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 200 kg (440 lb) |

| Length | 3.5 m (11 ft) |

| Wingspan | 2.5 m (8.2 ft) |

| Warhead weight | 50 kilograms (110 lb)[7] |

| Engine | MD-550 piston engine |

Operational range | 2,500 km (1,600 mi)[7] |

| Maximum speed | Around 185 km/h (115 mph) |

Guidance system | AI pilot,[8] GNSS, INS[9] |

Launch platform | Rocket-assisted take-off |

The HESA Shahed 136 (Persian: شاهد ۱۳۶, lit. 'Witness 136'), also known by its Russian designation Geran-2 (Russian: Герань-2, lit. 'Geranium-2'), is an Iranian-designed loitering munition,[10] also referred to as a kamikaze drone or suicide drone,[11][12][13][14] in the form of an autonomous pusher-propelled drone. It is designed and manufactured by the Iranian state-owned corporation HESA in association with Shahed Aviation Industries.[1][15][11]

The munition is designed to attack ground targets from a distance. The drone is typically fired in multiples from a launch rack. The first public footage of the drone was released in December 2021.[4] Russia has made much use of the Geran-2 in its invasion of Ukraine, especially in strikes against Ukrainian infrastructure.

Overview

Description

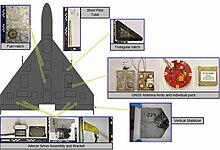

The aircraft has a cropped delta-wing shape, with a central fuselage blending into the wings and stabilizing rudders at the tips. The nose section contains a warhead estimated to weigh 30–50 kilograms (66–110 lb).[16] The engine sits in the rear of the fuselage and drives a two-bladed pusher propeller. The munition is 3.5 metres (11 ft) long with a wingspan of 2.5 metres (8.2 ft), flies at over 185 kilometres per hour (115 mph), and weighs about 200 kilograms (440 lb).[12] Range has been estimated to be anywhere from between 970–1,500 km (600–930 mi) to as much as 2,000–2,500 km (1,200–1,600 mi).[6][17][14] The U.S. Army unclassified worldwide equipment guide states that the Shahed 136 design supports an aerial reconnaissance option,[18][19] although no cameras were noted in the Geran-2 in Russian service.[20]

A British report presented to the United Nations Security Council states that a version of the Shahed 136 was used in 2023 against moving vessels in the Gulf of Oman, which required a sensor to lock onto the moving target, and/or an operator in the loop with a real time sensor feed. An Iridium satellite phone SIM card was found in the debris, indicating possible control beyond line of sight.[21]

Deployment

Because of the portability of the launch frame and drone assembly, the entire unit can be mounted on the back of any military or commercial truck.[12]

The aircraft is launched at a slight upward angle and is assisted in initial flight by rocket launch assistance (RATO). The rocket is jettisoned immediately after launch, whereupon the drone's conventional Iranian-made Mado MD-550 four-cylinder piston engine (possibly a reverse-engineered German Limbach L550E, also used in other Iranian drones such as the Ababil-3[citation needed]) takes over.[22]

Comms and guidance system

December 2023 remains from the drones were found with SIMs and 4G modems of the type used in mobile phones.[23]

Electronics

Despite no markings, experts believe the munition uses a computer processor manufactured by the American company Altera, RF modules by Analog Devices and LDO chips by Microchip Technology.[24]

Inspection of captured drones used by Russia during the 2022 invasion of Ukraine revealed that some Shahed-136 electronics were manufactured from foreign made components, such as a Texas Instruments TMS320 processor, a Polish made fuel pump on behalf of UK-based company TI Fluid Systems and a voltage converter from China.[25][26][27][28][excessive citations]

The Jewish Chronicle reported that dual-use technologies through British universities are used in development.[29]

In December 2023, the Ukrainian National Agency on Corruption Prevention stated that the Russian-produced Geran-2 included 55 parts made in the United States, 15 from China, 13 from Switzerland, and 6 from Japan.[30]

Geran-2

| Geran-2 | |

|---|---|

Remains of Geran-2 in March 2024 | |

| Type | Loitering munition |

| Place of origin | |

| Service history | |

| Used by | |

| Wars | |

| Production history | |

| Manufacturer | JSC Alabuga[31] |

| Unit cost | $30,000 to $80,000[32] |

| No. built | Unknown |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | maximum of 240 kg (530 lb)[33] |

| Length | 3.5 m (11 ft) |

| Wingspan | 2.5 m (8.2 ft) |

| Warhead weight | 52 kg (115 lb) and 90 kg (200 lb) options |

| Engine | MD-550 piston engine |

Operational range | 2,500 km (1,600 mi) or 1,000 km (620 mi) with 90 kg warhead[33] |

| Maximum speed | Around 185 km/h (115 mph) |

Guidance system | GNSS, INS[9] |

Launch platform | Rocket-assisted take-off |

Geran-2 is the name of the weapon in Russian service and later versions manufactured in Russia.[14][31] A The Times of Israel correspondent notes that the Iranian navigation system made from civilian components has been replaced with a Russian manufactured flight control unit and microprocessors, using the Russian GLONASS satellite navigation system rather than US civilian grade GPS, seemingly improving its loitering munition capability.[34][35] Geran-2 has labeling and paint color matching Russian rather than Iranian munitions,[36] some painted black for night operations.[33] No cameras or short-range sensors were noted in 2022.[20]

By November 2022, Russia and Iran had agreed to the Russian manufacture of the munition, with Iran exporting key components.[36][37] The Russian manufacturing facility is in the Alabuga Special Economic Zone, Tatarstan, with a target of building 6,000 Geran-2s by summer 2025.[38][39]

In July 2023, UK based Conflict Armament Research studied the remains of two Geran-2s used in Ukraine, concluding they were a new variant manufactured in Russia. They found "major differences in the airframe construction and in the internal units" compared to earlier examples studied, including a fuselage now made of fiberglass over woven carbon fiber rather than lightweight honeycomb. A third of the components showed manufacturing dates from 2020 to 2023, and three Russian components showed dates from January to March 2023. Twelve components showed dates after the start of the invasion in February 2022. Some internal modules were the same as in other Russian weapon systems, including the Kometa satellite navigation module.[40][41]

The Russian-manufactured Geran-2 is believed to have a "state-of-art antenna interference suppression" system that suppresses jamming of the satellite navigation position signal, designed by Iran using seven transceivers for input and an FPGA and three microcontrollers to analyse and suppress any electronic warfare emissions.[42] As of late September 2023, Russian forces have started packing warheads with tungsten ball shrapnel. Given that they are now manufacturing their own Shaheds Russian modifications include "new warheads (tungsten shrapnel), engines, batteries, servomotors and bodies", according to Ukrainian officials who research such weapons. The use of tungsten shrapnel is similar to the warhead on HIMARS GMLRS.[43]

As of October 2023, Russia had significantly hardened and upgraded the Geran-2 in several iterations, though the authors of an occasional paper in 2024 estimated this had increased the production cost from $30,000 to about $80,000. One such upgrade is for a scout Geran-2 to conduct an electromagnetic spectrum survey, transmitting back to assist in safer route planning for follow-on munitions.[32]

In May 2024, a version of the Geran-2 with a heavier 90 kg warhead was reported. This version has relocated internals and a smaller fuel tank, so has a reduced range likely greater than 1,000 kilometres (620 mi), still capable of reaching all areas of Ukraine. A 52 kg thermobaric warhead option was also reported. This version may be painted black for night operations.[31][33]

In July 2024 the CEO of Polish state-owned company WSK Poznan, which had supplied parts to Iran Motorsazan Company, was under investigation because in 2022 the parts ended up in a Geran-2 drone.[44]

Combat history

Yemeni Civil War

The drone has reportedly been used by the Houthis in the Yemeni Civil War during 2020.[45][better source needed]

There were some reports of its use in the 2019 attack of Saudi oil plants at Abqaiq and Khurais,[46][better source needed] however The Washington Post reported that other types of drone were used in that attack.[19] A British report to the United Nations Security Council states that a Shahed 131 was used, not a 136.[21]

Russian invasion of Ukraine

During the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russia has used loitering munitions bearing the name Geran-2 (Russian: Герань-2, literally "Geranium-2") against Ukraine. These Geran-2 drones are considered by Ukraine and its Western allies to be redesignated Iranian-made Shahed-136 drones.[47][48][49][50][excessive citations]

In the months prior to the confirmation of their use, US intelligence sources and Ukrainian officials have claimed that Iran had supplied Russia with several hundred drones including Shahed-136s, although Iran has repeatedly rejected the claims that it had sent drones for use in Ukraine, saying it is neutral in the war.[50][51][52][47][excessive citations] However, on 2 September 2022 the Commander of the IRGC General Hossein Salami said at a Tehran arms show that "some major world powers" had purchased Iranian military equipment and his men were "training them to employ the gear".[53] Russia stated it uses unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) of domestic manufacture.[54] This may reflect domestic production of these drones within Russia.

On 21 November 2022, a British government minister stated that the number of Shahed-136 loitering munitions used in Ukraine was estimated to be in the low hundreds.[55] In May 2023, the White House National Security Council spokesman suggested roughly 400 had been used so far, saying "Iran has provided Russia with more than 400 UAVs primarily of the Shahed variety".[56]

First appearances

On 13 September 2022, initial use of the Shahed 136 was indicated by photos of the remains of a drone inscribed with Russian: Герань-2, lit. 'Geranium'-2,[12] operated by Russian forces.[57] According to Rodion Kulahin, the Ukrainian artillery commander of the 92nd Brigade, Shahed 136 drones destroyed four howitzers and two BTRs during the Kharkiv counter-offensive.[58] On 23 September, further use of the drones was recorded in Odesa, where videos of their flyover and subsequent impact were uploaded on various Telegram channels. Notably, the drones were audibly engaged with small arms fire, which did not seem to have shot down any of the aircraft. On 25 September, videos posted on social media shows intensified use of the drone by the Russian forces around Odesa and Dnipro cities. This time, along with small arms, some form of anti-aircraft rotary cannon was employed, along with surface-to-air missiles, downing at least one Geran-2. A number of the drones were able to hit unknown targets, although there are claims the Ukrainian Navy Headquarters in Odesa was hit.[citation needed]

On 5 October 2022, a Geran-2 struck barracks hosting soldiers from the 72nd Mechanized Brigade in Bila Tserkva.[59]

Ukrainian soldiers said they can be heard from several kilometers away and are vulnerable to small arms fire.[60]

Ukrainian sources stated they deployed MiG-29 fighter aircraft to shoot down these drones with success, and that they used a similar strategy to shoot down cruise missiles such as the Kalibr.[61] However, on 13 October 2022, a Ukrainian MiG-29 crashed in Vinnytsia while attempting to shoot down a Geran-2. According to Ukrainian sources, the drone detonated near the jet and shrapnel struck the cockpit which forced the pilot to eject.[62][63]

October waves

Geran-2 drones participated in the October 2022 missile strikes that disabled large sections of the Ukrainian power grid.[64] Ukraine's military said it shot down the first Shahed 136 on September 13, and that 46 of the drones were launched on October 6, 24 on October 10, and 47 on October 17.[14]

In the morning of 17 October Kyiv was attacked again.[14] The drones were engaged by small-caliber ground fire as well as dedicated air-defense systems, but the drones reportedly hit several locations, including the offices of Ukrenergo. Other energy infrastructure facilities were also reported to be attacked, leading to blackouts around the affected infrastructure. Ukrainian Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal said the strikes hit critical energy infrastructure in three regions, knocking out electricity to hundreds of towns and villages.[65][66][67] At least 8 people were killed during the day's attack.[14]

The cost–benefit analysis of these drones compared to defending surface-to-air missile systems is in favor of the Shahed drones.[5] Loitering munitions downed after they have reached cities can lead to large-scale collateral damage from falling wreckage. Initially, the price of a Shahed-136 drone was estimated at between $20,000 and $50,000.[5] Leaked Iranian documents later indicated that in 2022, Iran had sold 6,000 Shahed-136s to Russia at a unit price of $193,000. According to the documents, Russia expected the unit cost to drop to $48,000 for drones manufactured domestically.[68] However, significant upgrades and hardening of the drones have increased the unit production cost to around $80,000 as of April 2024.[69]

The US Department of Defense has stated that a number of Iranian experts were deployed to Crimea to provide technical support for the drones used in the attacks.[70]

Ukrainian sources claim that more than 220 of these drones were shot down since 13 September.[19]

In December use of the munitions resumed after a three-week pause. Ukraine suggested the suspension was to modify them for cold weather,[71] but the British Ministry of Defence stated it was likely due to the exhaustion of previous stock followed by a resupply.[72] On 14 December, a Shahed-136 drone that exploded in Kyiv had “For Ryazan“ written on in Russian, a reference to attacks on the Dyagilevo air base in Ryazan.[73]

Ukrainian defense

While Ukraine's ground-based air defence covers the whole country at low to high altitude, the 'extra-low' altitude flight of the drones means that Ukraine's conventional ground-based air defences are at a disadvantage. The nation has implemented virtual observation posts, an alert app which allows civilians to submit drone sightings, and mobile fire groups that specialise in defending against drone attacks using missiles and various guns. One pilot describes the combination as 'pretty effective'.[citation needed]

Because the drones are small, slow, and fly at low altitude, they are hard to spot on MiG-29 radar. One Ukrainian MiG-29 pilot described the drone's appearance on radar as similar to a flock of birds. Ukraine's Soviet-era R-73 heat seeking missiles cannot lock on to targets inside clouds, while its R-27R semi-active radar homing missiles of similar age require a dangerously close approach when attacking drones. Ukrainian aircraft can intercept these drones using their 30mm cannon, but only in daylight and clear weather. With either guns or missiles, there are risks of severe damage to defending aircraft.[74]

Ukrainian forces introduced a system of networked microphones that would allow them to track the acoustic signature of incoming drones. Some 10,000 microphones are believed to be a part of the wireless network. The system is networked through a computer that turns the data into flight paths for Shahed drones. The microphone system was originally developed by two engineers in their garage. The microphones cost $4-500 per unit according to U.S. Air Force General James Hecker. The United States and Romanian militaries have shown interest in the system. Called "Sky Fortress" the estimated total value of the system is cheaper than "a pair of Patriot air-defense missiles".[75][76]

Night interceptions are harder as blackout conditions mean pilots have to rely on GPS to know whether they are over a population centre, lest a crashing drone cause collateral damage to civilian areas. In most such cases all the pilots can do is contact ground based air defences to intercept these drones.[77]

Ukraine's Air Force also believe that the drones are used to test the effectiveness of defences prior to missile attacks, to probe for weaknesses. Ukrainian pilot Vadym Voroshylov was credited with downing 5 Shahed drones in a week. However the explosion of the final drone downed his own MiG-29. Ukraine claims an interception rate of "65% and 85%".[78][79][80][81][excessive citations]

A Ukrainian defense attaché in the United States stated that SA-8 missiles and both the Soviet-era ZSU-23-4 and the German-supplied Flakpanzer Gepard SPAAGs have been used to "great effect" against these "relatively crude" drones.[82]

In early November 2022, Forbes reported on Ukrainian efforts to seek "Shahed catchers." Because legacy anti-aircraft weapons are less suited to intercepting swarms of cheap drones, various dedicated counter-UAS systems are being acquired. One is the Anvil made by Anduril Industries, which uses a suite of sensors powered by the company's AI Lattice system to detect and track threats then passes information to Anvil interceptors, which weigh 12 lb (5.4 kg) and have backwards-facing propellers to ram into a target at over 100 mph (160 km/h). Another is the NiDAR made by MARSS, which has a similar networked sensor package and uses ducted fan quadcopter interceptors that have a top speed of more than 170 mph (270 km/h). There are also domestic Ukraine options such as the Fowler. All systems are similar in that they use a large number of small interceptors to be able to counter drones launched en-masse simultaneously approaching from different directions.[83]

DShK machine guns fitted with thermal imaging or cameras are among the most cost effective weapons for shooting down these drones. Some are working with searchlights like during World War 2.[84][85][86]

According to a Wall Street Journal analysis of data from the Ukrainian Air Force Command in May 2024, Russia had launched 2,628 Shahed drones in the previous six months, some to test Ukrainian air defenses before other missiles were launched, of which Ukraine had intercepted over 80%. However the Wall Street Journal also noted "Ukraine uses such statistics for propaganda purposes".[87]

During August 2024 a Ukrainian Mi-8 used a machine gun to shoot down a Shahed drone. Earlier a Mi-24P used its twin GSh-30K 30mm cannons to also shoot down a drone. Such weapons are considered more cost effective compared using air defence missiles.[88]

On 8 September 2024, Russian drones entered both Romanian and Latvian airspace. Romanian scrambled two F-16s to monitor the drone's progress, it landed "in an uninhabited area" near Periprava, according to the Romanian Ministry of Defence. The drone that entered Latvian airspace from Belarus crashed near Rezekne. This comes as the ISW noted increased success in Ukrainian electronic warfare against Russian drones that resulted in "several Russian Shahed drones (that) recently failed to reach their intended targets for unknown reasons." Two Kh-58s also reportedly failed to reach their targets. The ISW also claimed that use of electronic warfare also saved air defence resources.[89][90][91]

On 10 October 2024, a Neptune missile struck an ammunition depot in Oktyabrsky, Krasnodar. Ukrainian intelligence claimed to have destroyed over 400 Shahed UAVs.[92]

Production in Russia

Russia acquired the right to produced Shahed drones domestically. Due to labor shortage, African labor is present on the production line, under strict surveillance, deceitful remuneration and poor safety conditions.[93]

Reactions

In response to the initial attacks, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has denounced it as "a collaboration with evil". Diplomatic ties between Iran and Ukraine were subsequently reduced as a consequence of the attacks.[94]

On 18 October 2022 the U.S. State Department accused Iran of violating United Nations Security Council Resolution 2231 by selling drones to Russia, agreeing with similar assessments by France and the United Kingdom. On 22 October France, Britain and Germany formally called for an investigation by the UN team responsible for UNSCR 2231.[95] Iran's ambassador to the UN responded that these accusations were an erroneous interpretation of paragraph 4 of annex B of the resolution, which clearly states it applies to items that "could contribute to the development of nuclear weapon delivery systems", which these drones could not.[96][97] Resolution 2231 was adopted after the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) was signed. The U.S. withdrew from the agreement under the Donald Trump administration in 2018.[98][52][51] The embargo on conventional Iranian arms ended in October 2020, but the restrictions on Iran regarding missiles and related technologies are in place until October 2023.[99]

An Iranian Major-General said 22 countries requested to purchase Iranian drones.[100][101]

Multiple critics including a senior researcher of the Center for Security Studies called the weapon tactically useless, and said that its role is as a weapon of terror against civilians.[102][103][104][105][excessive citations] Others said it can be used to carried out devastating strikes to Ukrainian forces but are unlikely to be a game-changer for the war.[106]

Iran denied sending arms for use in the Ukraine war and Iranian foreign minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian said Iran will not remain indifferent if it is proven that Russia used Iranian drones in the war against Ukraine.[107][108][109] On 5 November 2022, Abdollahian said Iran shipped "a small number" of drones to Russia before the war. He repeated Iran will not remain indifferent if proven Russia used Iranian drones against Ukraine. He denounced Ukraine for not showing up at talks to discuss evidence of Russian use of Iranian drones.[110] Iran foreign ministry continued to deny sending weapons for use in the war.[111]

2022 Syria and Iraqi Kurdistan

The U.S. military believes groups allied to Iran used the Shahed 136 in August 2022 against a U.S.-run military base at Al-Tanf in Syrian opposition controlled territory in the Syrian Desert.[19]

In 2022, the IRGC Ground Forces used the Shahed 136 drone in attacks on headquarters of Kurdish separatist group in the Kurdistan region of Iraq.[112]

2023 Indian Ocean

On 24 November, it was suspected that an Iranian Shahed 136 had been used to attack the CMA CGM bulk carrier Symi in the Indian Ocean according to a US defense official. The attack caused damage to the ship but did not injure any of the crew.[113]

2024 Iranian strikes on Israel

On 13 April 2024, Iran carried out a missile and drone attack against Israel, which used the Shahed 136 among other long range weapons. The attack was largely intercepted and thwarted by missile interception systems of Israel, the United States, Jordan, the United Kingdom and France on 14 April.[114] The direct line distance from the Iranian border to one of the targets, Nevatim Airbase, is about 1,050 kilometres (650 mi).[115] On 18 April, the United States imposed new sanctions on sixteen Iranian individuals as well as two companies associated with Iran's drone program.[116]

Classification controversy

The classification of the Shahed 136 as a loitering munition has been disputed due to an apparent lack of loitering capability.[117] In January 2023, the Royal United Services Institute, a British defense and security think tank, called into question the classification of the Shahed 136 as a loitering munition.[17] RUSI noted that the Shahed 136 had mainly been used for point-to-point suicide missions similar to cruise missiles, rather than loitering around a target area before striking a target. However, RUSI also stated that the Shahed 136 may have been used during the attacks on the MT Mercer Street and Pacific Zircon, hinting at the existence of a loitering munition variant even if the original Shahed 136 does not have that capability.[17] An Oil Companies International Marine Forum report assessing the Shahed 136 attacks on those ships stated that the wreckage of the drones used in the attacks did not produce any sensors or a laser seeking equipment found on traditional loitering munitions. However, the report also noted, based on photographic evidence, that the drone that struck the Pacific Zircon was equipped with a GNSS antenna.[118]

Relations with other Shahed drones

Shahed 131

The Shahed 136 is visually similar to the smaller Shahed 131, differing mainly by its wingtip stabilisers extending up and down rather than only up on the Shahed 131.[119] The Shahed 131 has a simple inertial navigation system (INS) and a GPS with some electronic warfare protection, which the Shahed 136 may also have.[120]

Shahed 238

In September 2023, a trailer for an Iranian state TV documentary on Iranian drone development revealed the existence of a Shahed 136 version powered by a turbojet engine. Jet propulsion would give the one-way attack UAV greater speed and altitude, making it more difficult to intercept compared to the propeller-driven version, a large percentage of which have been able to be shot down in Ukraine by anti-aircraft cannons and even small arms. It also has a nose-mounted camera which could improve navigation or enable terminal guidance. A jet version would be more expensive and complex to manufacture, have reduced range, and have a larger thermal signature making it vulnerable to infrared-guided missiles.[121][13] The jet-powered strike drone was publicly unveiled on 20 November 2023 as the Shahed 238.[122]

Operators

In September 2023, the president of Iran, Ebrahim Raisi, denied providing the drones to Russia for use in Ukraine.[123]

The drones will also be foreign produced at Gomel, Belarus and they are produced in the drone factory in Yelabuga.[125][126]

According to leaked documents, the provenance of which are unclear, the Russian military in 2022 paid $1.75 billion in gold bullion for the import of 6000 Shahed 136 units.[127] These documents also state that with near full Russian localization the projected cost is $48,800 per unit.[128] Based on these documents, Anton Gerashchenko stated the cost of each Shahed 136 was believed to be $193,000 per unit when ordering 6,000 drones and about $290,000 per unit when ordering 2,000.[2]

See also

Related development

- HESA Ababil

- Shahed drones

- Shahed 121

- Shahed 129

- Shahed 131, or Geran-1

- Shahed 149 Gaza

- Shahed 171 Simorgh

- Shahed 238

- Italmas

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- AeroVironment Switchblade

- Garpiya

- IAI Harop

- IAI Harpy

- Samad (UAV)

- WB Electronics Warmate

- ZALA Lancet

Related lists

References

- ^ a b "Treasury Targets Actors Involved in Production and Transfer of Iranian Unmanned Aerial Vehicles to Russia for Use in Ukraine". U.S. Department of the Treasury (Press release). 15 November 2022. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

Shahed Aviation Industries Research Center (SAIRC), subordinate to the IRGC ASF, has designed and manufactured several Shahed-series UAV variants, including the Shahed-136 one-way attack UAV ...

- ^ a b Buncombe, Andrew (7 February 2024). "Russia paid Iran 'in gold bullion' for drones used in attacks on Ukraine". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ Segura, Cristian (12 October 2022). "Iranian 'suicide' drones: Russia's new favorite weapon in Ukraine war". El Pail. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ a b Newdick, Thomas. "Russia Bombards Ukraine With Iranian 'Kamikaze Drones'". The Drive. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ a b c Boffey, Daniel (19 October 2022). "Financial toll on Ukraine of downing drones 'vastly exceeds Russian costs'". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ^ a b Gordon, Chris (20 January 2023). "Cheap UAVs Exact High Costs". Air & Space Forces Magazine. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ a b "IRGC confirms specs for Shahed-136 attack UAV". Janes Information Services. 17 May 2023. Archived from the original on 28 May 2023.

- ^ https://en.defence-ua.com/weapon_and_tech/whats_the_russias_new_ai_powered_shahed_136_and_what_its_capable_of-13011.html

- ^ a b Dangwal, Ashish (19 October 2022). "Russia Has 'Upgraded' Iranian Shahed-136 Kamikaze Drones to Boost Its Lethality & Accuracy -- Military Experts". eurasiantimes.com. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ Kahn, Lauren (26 October 2022). "Can Iranian Drones Turn Russia's Fortunes in the Ukraine War?". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 26 November 2023.

The Iranian-produced Shahed-136 (renamed by Russia as the Geran-2) is a loitering munition, although it is sometimes misleadingly referred to in media as a kamikaze or suicide drone.

- ^ a b "UK sanctions Iran over kamikaze Russian drones". gov.uk. 18 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Iranian Shahed-136 Kamikaze Drones Already Used By Russia". Defense Express. Kyiv. 13 September 2022. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ^ a b Iran Unveils Jet-Powered Version Of Shahed Kamikaze Drone. Forbes. 27 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Barrie, Douglas (17 October 2022). "Explainer: Russia Deploys Iranian Drones". United States Institute of Peace. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- ^ "Ukrainian experts identify Iranian producer of Shahed drones" (Press release). Kyiv: Ukrinform. 10 December 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

The Shahed-131\136 type one-way attack drones, which Russia has been using to attack Ukraine since September 2022, are produced by the Iranian state-run Iran Aircraft Manufacturing Industrial Company

- ^ "How are 'kamikaze' drones being used by Russia and Ukraine?". BBC News. 18 October 2022. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- ^ a b c "Russia's Iranian-Made UAVs: A Technical Profile". Royal United Services Institute. 13 January 2023.

- ^ "Shahed-136 Iranian Loitering Munition Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)". OE Data Integration Network (ODIN). U.S. Army. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

Camera Equipment: design supports photographic equipment providing still and / or real-time image / video results

- ^ a b c d Harris, Shane; Lamothe, Dan; Horton, Alex; DeYoung, Karen (20 October 2022). "U.S. has viewed wreckage of kamikaze drones Russia used in Ukraine". Washington Post. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

The Houthis claimed to have used Samad-3 drones to attack a refinery in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, last spring, and launched Samad-1 drones at Saudi Aramco facilities in other parts of the country. Those drones are distinct from the weapons used by Russia in Ukraine.

- ^ a b Latynina, Yulia (24 October 2022). "A portrait of a Shahed in the sky of Ukraine". Novaya Gazeta Europe. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- ^ a b "UK presentation of evidence of UNSCR 2231 violations" (PDF). United Nations Security Council. 18 May 2023. S/2023/362. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ "Shahed-136: іранські дрони-камікадзе, які видають звук "мопеда" та вибухають у вказаній точці" [Shahed-136: Iranian kamikaze drones that make a "moped" sound and explode at a specified point]. ТСН.ua (in Ukrainian). 5 October 2022. Archived from the original on 12 October 2022. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ^ "Shahed-136 with Cellular Modem Found in Ukraine: What It Means". 30 November 2023.

- ^ "An Advanced Radio Communication Device on American Processors Found in the Shahed-136". Defense Express. Kyiv. 6 October 2022. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ^ Milmo, Cahal; Kirby, Dean (10 May 2022). "Iranian drones 'manufactured with British and US components' used to bombard Ukraine". headtopics.com.

- ^ Nissenbaum, Dion (12 June 2023). "Chinese Parts Help Iran Supply Drones to Russia Quickly, Investigators Say". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "China providing parts to Iran drones for Russia invasion, report reveals". Middle East Monitor. 13 June 2023. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ Ladden-Hall, Dan (12 June 2023). "Chinese Parts Helping Iran's Speedy Supply of Drones to Russia: Report". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ Rose, David; Pope, Felix (8 June 2023). "Iran's 'suicide drones' being developed at UK universities". The Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ Fornusek, Martin (19 December 2023). "Most of 2,500 foreign components Ukraine found in Russian weapons come from US". The Kyiv Independent. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ a b c Albright, David; Burkhard, Sarah; Faragasso, Spencer (9 May 2024). "Alabuga's Shahed 136 (Geran 2) Warheads: A Dangerous Escalation" (PDF). Institute for Science and International Security. pp. 6–13. Retrieved 6 August 2024.

- ^ a b Bronk, Justin; Watling, Jack (11 April 2024). "Mass Precision Strike: Designing UAV Complexes for Land Forces" (PDF). Royal United Services Institute. p. 31,37. ISSN 2397-0286. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d Wolf, Fabrice (15 July 2024). "GERAN-2, From low-cost missile to lurking ammunition". Meta-defense Publication. France. Retrieved 6 August 2024.

- ^ Portnoy, Alexander (30 October 2022). "Do Iranian drones attack Ukraine? Myths and truth". The Times of Israel blog. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- ^ Bryen, Stephen (26 October 2022). "Israel's strategic interest in Ukraine is changing because of Iran". Center for Security Studies. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- ^ a b Warrick, Joby; Mekhennet, Souad; Nakashima, Ellen (19 November 2022). "Iran will help Russia build drones for Ukraine war, Western officials say". Washington Post. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- ^ Abrahams, Jessica; Kilner, James (20 November 2022). "Moscow strikes deal with Iran to build own kamikaze drones in Russia". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ Bennett, Dalton; Ilyushina, Mary (17 August 2023). "Inside the Russian effort to build 6,000 attack drones with Iran's help". Washington Post. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ Cook, Chris; Seddon, Max; Stognei, Anastasia; Schwartz, Felicia (6 July 2023). "Russia deploys 'Albatross' made in Iran-backed drone factory". Financial Times. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ Ismay, John (10 August 2023). "Russia Is Replicating Iranian Drones and Using Them to Attack Ukraine". New York Times. Retrieved 14 October 2023.

- ^ "Documenting the domestic Russian variant of the Shahed UAV". Conflict Armament Research. August 2023. Retrieved 14 October 2023.

- ^ Albright, David; Burkhard, Sarah (14 November 2023). "Electronics in the Shahed-136 Kamikaze Drone" (PDF). Institute for Science and International Security. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ HOWARD ALTMAN (28 September 2023). "Russia's Shahed-136 Drones Now Feature Tungsten Shrapnel". The War Zone. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ Ptak, Alicja (19 July 2024). "Polish state firm sold parts used in Iranian "suicide drones" deployed by Russia in Ukraine".

- ^ a b O'Connor, Tom (13 January 2021). "Exclusive: Iran deploys "suicide drones" in Yemen as Red Sea tensions rise". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ^ Hambling, David (13 September 2022). "Russia Is Now Using Iranian 'Swarming' Attack Drones In Ukraine — Here's What We Know". Forbes contributor. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ a b Beaumont, Peter (29 September 2022). "Russia escalating use of Iranian 'kamikaze' drones in Ukraine". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 September 2022. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ^ "Russia-Ukraine war News: Ukraine to reduce Iran embassy presence over Russia drone attacks". Al Jazeera. 24 September 2022. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- ^ Hird, Karolina; Bailey, Riley; Mappes, Grace; Barros, George; Kagan, Frederick W. (12 October 2022). "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, October 12". Institute for the Study of War. Washington, DC. Archived from the original on 14 October 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ a b Motamedi, Maziar (19 October 2022). "Iran says ready to talk to Ukraine on claims of arming Russia". aljazeera.com. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ^ a b Kanaani, Nasser (18 October 2022). "Iranian foreign ministry spokesman reacts to some claims about shipment of arms including military drones by Iran to Ukraine". Iranian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- ^ a b Kennedy, Niamh; Mahmoodi, Negar; Kottasová, Ivana; Raine, Andrew (16 October 2022). "Iran denies supplying Russia with weapons for use in Ukraine". CNN. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- ^ "IRGC Chief: Iran Selling Arms to World Powers". No. 106464. kayhan.ir. 2 September 2022. Archived from the original on 2 September 2022.

Iran has sold homegrown military equipment to foreign customers, including some major world powers, and is training them to employ the gear, Commander of the Islamic Revolution Guards Corps (IRGC) Major General Hussein Salami said. During a visit to an exhibition of the air defense and electronic products of the Iranian Defense Ministry on Thursday, the IRGC commander said efforts by local elites and experts in the military and defense industries have resulted in the development of indigenous technologies.

- ^ "Kremlin has no information about purchase of Iranian drones for Russia — spokesman". TASS. Moscow. 18 October 2022. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- ^ Heappey, James (21 November 2022). "Russia: Iran". UK Parliament. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Madhani, Aamer; Long, Colleen; Miller, Zeke (15 May 2023). "Russia aims to obtain more attack drones from Iran after depleting stockpile, White House says". Associated Press. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ Dangwal, Ashish (13 September 2022). "1st Evidence Of Russia-Operated Iranian Suicide Drone Emerges in Ukraine; Kiev Claims Downing Shahed-136 UAV". Latest Asian, Middle-East, EurAsian, Indian News. Archived from the original on 19 September 2022. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ "Russia's Use of Iranian Kamikaze Drones Creates New Dangers for Ukrainian Troops". The Wall Street Journal. 17 September 2022. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ Malsin, Jared; Coles, Isabel (5 October 2022). "Russia Uses Iranian-Made Drones to Strike Military Base Deep Inside Ukraine". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Ukrainian soldiers tell how they deal with Iranian kamikaze drones used by Russia". The New Voice of Ukraine. 7 October 2022. Archived from the original on 7 October 2022. Retrieved 8 October 2022 – via Yahoo! Finance News.

- ^ "For the First Time Ukrainian Air Force Uses MiG-29 Fighters to Eliminate Drones Against Shahed-136". Defense Express. Kyiv. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ "ДБР з'ясовує причини падіння військового літака на Вінниччині під час знищення ворожих безпілотників (ВІДЕО) - Державне бюро розслідувань" [The SBI investigates the reasons for the downing of a military plane in Vinnytsia during the destruction of enemy drones (VIDEO) - State Bureau of Investigation]. dbr.gov.ua. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ^ Newdick, Thomas (13 October 2022). "Ukraine Claims MiG-29 Pilot Downed Five Drones Before Ejecting". The Drive. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ "Zelensky: Russia used Iran-made drones, missiles in deadly strikes on several cities". Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 10 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ ""Suicide drones" attack Kyiv, other Ukrainian cities". CBS News. 17 October 2022. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ Khurshudyan, Isabelle; Timsit, Annabelle; Khudov, Kostiantyn (17 October 2022). "Drones hit Kyiv as Russia aims to destroy Ukraine power grid before winter". The Washington Post. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- ^ "Energy facilities in Ukraine's north, center damaged by Russian strikes – Ukrenergo". Ukrinform. 17 October 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- ^ Yaron, Oded (21 February 2024). "Gold for Drones: Massive Leak Reveals the Iranian Shahed Project in Russia". Haaretz.

- ^ Bronk, Justin; Watling, Jack (11 April 2024). "Mass Precision Strike: Designing UAV Complexes for Land Forces" (PDF). Royal United Services Institute. p. 31. ISSN 2397-0286.

- ^ Wright, George (21 October 2022). "Ukraine war: Iranian drone experts 'on the ground' in Crimea - US". BBC News. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- ^ "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, December 7". Institute for the Study of War. 7 December 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "UK Defense Ministry: Russia likely started using new batch of Iranian drones in Ukraine". The Kyiv Independent. 9 December 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Balmforth, Tom; Polityuk, Pavel (14 December 2022). "Russia launches drone attack on Kyiv, Ukraine hails air defences". Reuters. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ Newdick, Thomas (13 December 2022). "Inside Ukraine's Desperate Fight Against Drones With MiG-29 Pilot "Juice"". thedrive.com. Retrieved 7 September 2024.

"It's pretty effective because they are spread around the country, and they have good readiness as our command-and-control network is warning them,"

- ^ Audrey Decker (13 July 2024). "Ukraine's cheap sensors are helping troops fight off waves of Russian drones". Defense One. Retrieved 7 September 2024.

- ^ JOSEPH TREVITHICK (12 February 2024). "Ukraine Using Thousands Of Networked Microphones To Track Russian Drones". TWZ. Retrieved 7 September 2024.

- ^ THOMAS NEWDICK (13 December 2022). "Inside Ukraine's Desperate Fight Against Drones With MiG-29 Pilot "Juice"". TWZ. Retrieved 7 September 2024.

With a cruise missile, the higher speed and resulting Doppler effect mean the MiG's radar has an easier job of detecting the threat, but a slow-flying Shahed can easily get lost among the rooftops and other ground clutter.

- ^ Newdick, Thomas (15 December 2022). "A MiG-29 Pilot's Inside Account Of The Changing Air War Over Ukraine". thedrive.com. Archived from the original on 15 December 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ Balmforth, Tom (23 December 2022). "Ukraine's 'cat and mouse' battle to keep Russian missiles at bay". Reuters. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ Cenciotti, David (8 December 2022). "Maj. Vadym Voroshylov snapped a selfie after a night ejection from his MiG-29 Fulcrum". The Aviationist. Archived from the original on 25 December 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ Knights, Michael; Almeida, Alex (10 November 2022). "What Iran's Drones in Ukraine Mean for the Future of War". The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ Sprenger, Sebastian (6 October 2022). "Ukraine to target Russia's bases of Iran-supplied explosive drones". defensenews.com. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- ^ Hambling, David (2 November 2022). "'Shahed Catchers': Ukraine Will Deploy Interceptor Drones Against Russian Kamikazes". Forbes. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ Satam, Parth (5 January 2023). "Ukraine Uses Powerful Searchlights & Anti-Aircraft Guns To Neutralize Russian Geran-2 UAVs Used During Night Strikes". eurasiantimes.com. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ^ Newdick, Thomas (13 December 2022). "Inside Ukraine's Desperate Fight Against Drones With MiG-29 Pilot "Juice"". thedrive.com. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ^ Roblin, Sebastien (11 December 2022). "To Stop Killer Drones, Ukraine Upgrades Ancient Flak Guns With Consumer Cameras And Tablets". forbes.com. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ^ MacDonald, Alistair; Brinson, Jemal R.; Brown, Emma; Sivorka, Ievgeniia (13 May 2024). "Russia's Bombardment of Ukraine Is More Lethal Than Ever". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 13 May 2024.

- ^ OLENA MUKHINA (23 August 2024). "Pentagon reveals details of new US military aid package to Ukraine". euromaidanpress. Retrieved 23 August 2024.

- ^ "NATO members Romania, Latvia report Russian drones breach airspace". Reuters. 9 September 2024. Retrieved 10 September 2024.

- ^ OLHA HLUSHCHENKO (9 September 2024). "Ukraine successfully adapting and developing capabilities to counter Russian UAVs – ISW". Reuters. Retrieved 10 September 2024.

- ^ Christina Harward; Riley Bailey; Nicole Wolkov; Davit Gasparyan; George Barros (8 September 2024). "RUSSIAN OFFENSIVE CAMPAIGN ASSESSMENT, SEPTEMBER 8, 2024". ISW. Retrieved 10 September 2024.

- ^ Kapil Kajal (10 October 2024). "400 Shahed UAVs burned as Ukraine hits Russian drone base with new cruise missile". Interesting Engineering. Retrieved 10 October 2024.

- ^ "Africans recruited to work in Russia say they were duped into building drones for use in Ukraine". AP News. 10 October 2024. Retrieved 10 October 2024.

- ^ Ljunggren, David (23 September 2022). "Ukraine to slash ties with Iran over 'evil' drones supply to Russia". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 September 2022. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ^ "European countries urge UN probe of Iran drones in Ukraine". France 24. 22 October 2022. Archived from the original on 22 October 2022.

France, Britain and Germany called Friday in a letter to the United Nations for an "impartial" investigation into Iranian drones the West says Russia is using in the war in Ukraine. "We would welcome an investigation by the UN Secretariat team responsible for monitoring the implementation of UNSCR 2231," the UN ambassadors of the three countries wrote.

- ^ Iravani, Amir Saeid (19 October 2022). "Letter dated 19 October 2022 from the Permanent Representative of the Islamic Republic of Iran to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General" (PDF). United Nations Security Council. S/2022/776. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Iravani, Amir Saeid (24 October 2022). "Letter dated 24 October 2022 from the Permanent Representative of the Islamic Republic of Iran to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council" (PDF). United Nations Security Council. S/2022/794. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine war: US says Iranian drones breach sanctions". BBC News. 18 October 2022. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- ^ Lederer, Edith M. (19 October 2022). "Ukraine accuses Iran of violating UN ban on transferring drones". PBS. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "The rise of Iran's drone industry". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ "22 countries seek to buy Iranian drones: general". Tehran Times. 18 October 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Gsteiger, Fredy (19 October 2022). "Russland setzt auf Kamikaze-Drohnen aus Iran" [Russia bets on kamikaze-drones from Iran] (in German). SRF. Retrieved 22 October 2022. ["These dones don't win a battle but it is possible to terrorize the population" (minute 4:30)]; "Kamikaze-Drohnen sind militärisch nutzlos – aber trotzdem wirksam" [Kamikaze-Drones are militarily useless - but nevertheless effective] (in German). SRF. 19 October 2022. Retrieved 22 October 2022. [«The iranian Schahed-136-Drones fired by Russia are neither maneuverable nor precise.»]

- ^ "Russland-Experte vermutet Plan, der den Westen treffen soll: Bringen Kamikaze-Drohnen Putin die Kriegs-Wende?" [Russia expert suspects plan that should hit the West: will kamikaze drones bring the war to Putin?]. merkur.de. 24 October 2022.

- ^ "EXPLAINER: Killer drones vie for supremacy over Ukraine". Associated Press. 18 October 2022.

Instead, the Shahed is simply launched in bunches in order to overwhelm defenses, particularly in civilian areas. 'They know that most will not make it through,' he said.

- ^ "Wie einst Hitler mit der V1-Rakete: Russland sucht sein Heil in billigen Terrorwaffen" [Like Hitler with the V1 rocket: Russia seeks salvation in cheap terror weapons]. watson. 17 October 2022.

- ^ Trofimov, Yaroslav; Nissenbaum, Dion (17 September 2022). "Russia's Use of Iranian Kamikaze Drones Creates New Dangers for Ukrainian Troops". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ "Iran says won't remain 'indifferent' if Russian use of its drones in Ukraine proven". Al Arabiya English. AFP. 24 October 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ Iran Foreign Ministry [@irimfa_en] (25 October 2022). "We have not handed over any drones or weapons to #Russia to be used in the war against #Ukraine" (Tweet). Retrieved 2 November 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ Iran Foreign Ministry [@irimfa_en] (25 October 2022). "We are confident that there is no change in the position of the Islamic Republic of #Iran regarding the war in #Ukraine and there will be no change in future either" (Tweet). Retrieved 2 November 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ Peleschuk, Dan; Ljunggren, David (5 November 2022). "Iran acknowledges drone shipments to Russia before Ukraine war". Reuters. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ "Iran opposes Ukraine war, supports peace and a ceasefire". Mehr News Agency. 11 November 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "VIDEO: Moment when Shahed-136 drone hits terrorists bases". Mehr News Agency. 2 October 2022. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ "An Israeli-owned ship was targeted in suspected Iranian attack in Indian Ocean, US official tells AP". AP News. 25 November 2023. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ Rothwell, James (13 April 2024). "The Shahed drone: Iran's low-cost but deadly weapon of choice". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- ^ "Iranian border to Nevatim Airbase" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- ^ Liptak, Kevin (18 April 2024). "US slaps new sanctions on Iran's drone program as Israel considers response to weekend attack". CNN. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ Sof, Eric (20 October 2022). "HESA Shahed 136: A cheap and deadly Iranian kamikaze drone". Spec Ops Magazine. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Loitering Munitions – The Threat to Merchant Ships" (PDF). August 2023.

- ^ Binnie, Jeremy (29 September 2022). "Ukraine conflict: Details of Iranian attack UAV released". Janes. IHS. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ^ "Not Only Shahed-136: a Detailed Study of Another Iranian Shahed-131 Kamikaze Drone Used by Russia". Defense Express. Kyiv. 24 September 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ^ "IRGC documentary shows jet-powered Shahed-136 UAV variant". Janes Information Services. 3 October 2023. Archived from the original on 5 October 2023.

- ^ Iran officially unveils new jet-powered Shahed-238 drone. Army Recognition. 22 November 2023.

- ^ "Iranian President addresses relationship with Russia". NBC News.

- ^ "Tripling of Iraqi Militia Claimed Attacks on Israel in October | The Washington Institute". www.washingtoninstitute.org. Retrieved 24 October 2024.

- ^ Starr, Michael (10 May 2023). "Iran may produce Shahed drones for Russia in Belarus - report". Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ Post, Kyiv; Struck, Julia (28 May 2024). "Russian Plant in Tatarstan to Produce 6,000 Shahed Drones Annually". Kyiv Post. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ Altman, Howard (8 February 2024). ""What Does a Shahed-136 Really Cost"". The WarZone. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ "The cost of Shahed-136 for Russia has been reported". Ukrainian Military Center. 6 February 2024. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

External links

Media related to Shahed 136 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Shahed 136 at Wikimedia Commons- Animated Video: Kamikaze drone Iran Shahed 136 | How it Works #AiTelly's channel on YouTube. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- HESA aircraft

- Shahed aircraft

- Military equipment of Iran

- Unmanned aerial vehicles of Iran

- Unmanned military aircraft of Iran

- Aircraft manufactured in Iran

- Iranian military aircraft

- Single-engined pusher aircraft

- High-wing aircraft

- V-tail aircraft

- Military equipment of the Russian invasion of Ukraine

- Loitering munition