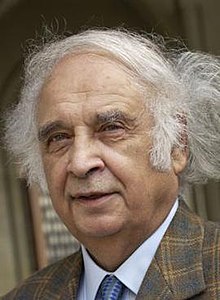

Serge Moscovici

Serge Moscovici | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Srul Herş Moscovici 14 June 1925[1] Brăila, Romania |

| Died | November 15, 2014 (aged 89) Paris, France |

| Alma mater | University of Paris |

| Occupation(s) | Psychologist Political ecology |

| Political party | Romanian Communist Party; The Greens (France) |

| Spouse | Marie Broomberg |

| Relatives | Pierre Moscovici (son) |

Serge Moscovici (June 14, 1925 – November 15, 2014)[2] born Srul Herş Moscovici, was a Romanian-born French social psychologist, director of the Laboratoire Européen de Psychologie Sociale ("European Laboratory of Social Psychology"), which he co-founded in 1974 at the Maison des sciences de l'homme in Paris. He was a member of the European Academy of Sciences and Arts and Commander of the Legion of Honour, as well as a member of the Russian Academy of Sciences and honorary member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Moscovici's son, Pierre Moscovici is the current First President of the Court of Audit and was European Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs, Taxation and Customs and Minister of Finance.

Biography

[edit]Born in Brăila, Romania to parents who were grain merchants,[3][4] His uncle was Ilie Moscovici, a leading Romanian socialist. Moscovici frequently relocated, together with his father, spending time in Cahul, Galaţi, and Bucharest.[3][4] (Later he would indicate that his stay in Basarabia had contributed to his image of a homeland.[4]) From an early age Moscovici suffered the effects of antisemitic discrimination: in 1938, he was expelled from a Bucharest high school on the basis of newly-issued antisemitic legislation.[3][4][5] In later years he commented on the impact of the Iron Guard, and expressed criticism for intellectuals associated with it (Emil Cioran and Mircea Eliade).[4]

Moscovici trained as a mechanic at the Bucharest vocational school Ciocanul.[4] Faced with an ideological choice between Zionism and Communism, he opted for the latter, and, in 1939, joined the then-illegal Romanian Communist Party, being introduced by a clandestine activist whom he knew by the pseudonym Kappa.[4]

During World War II, Moscovici witnessed the Iron Guard-instigated Bucharest Pogrom in January 1941. Later the Ion Antonescu régime interned him in a forced-labor camp, where, together with other persons of his age, he worked on construction teams until freed by the Soviet Red Army in 1944.[3][4][5] During those years he taught himself French and educated himself by reading philosophical works (including those of Baruch Spinoza and René Descartes).[3][5]

Subsequently, Moscovici travelled extensively, notably visiting Mandatory Palestine, Germany and Austria.[3] During the late stages of World War II he met Isidore Isou, the founder of lettrism, with whom he founded the artistic and literary review Da towards the end of 1944 (Da was quickly suppressed by the authorities).[5] Refusing promotion on the basis of political affiliation at a time when the Communist Party participated in Romania's governments, he became instead a welder in the large Bucharest factory owned by Nicolae Malaxa.[4]

Initially welcoming Soviet occupation, Moscovici grew increasingly disillusioned with communist politics, and noted the incidence of antisemitism among Red Army soldiers.[6] As the communist regime was taking over and the Cold War started, he helped Zionist dissidents cross the border illegally.[4] For this, he was involved in a 1947 trial held in Timișoara, and decided to leave Romania definitively.[4] Choosing clandestine immigration, he arrived in France a year later, having passed through Hungary and Austria, and having spent time in a refugee camp in Italy.[3][4][5]

In Paris, helped by a refugee fund, he studied psychology at the Sorbonne while employed by an industrial enterprise.[3][5] At the time, Moscovici became close to Paris-based writers, including the Romanian-born Jewish Paul Celan and Isac Chiva.[3][7] In reference to himself, Celan, and Moscovici, Chiva later recalled:

"For us, people on the Left, but who had fled communism, the first period in Paris, in a capital where the intellectual environments were developing under full-scale Stalinist enthusiasm, was very harsh. We were caught between a rock and a hard place: on one side, the French university environment who saw us as «fascists». [...] On the other, the Romanian exiles, most of all the nationalist students, when not outright on the far right, who did not shy away from denouncing us as communist «moles» in the pay of Bucharest or Moscow."[7]

In 1955, he married Marie Bromberg who he met at the Institute de Psychologie. They had two sons, Pierre and Denis.[8]

In 1961, he completed His doctoral thesis (La psychanalyse, son image et son public). It was directed by the psychoanalyst Daniel Lagache and explored the social representations of psychoanalysis in France.[5] Moscovici also studied epistemology and history of sciences with philosopher Alexandre Koyré. He worked initially in the Social Psychology Laboratory, created on rue de la Sorbonne by Daniel Lagache.

During the 1960s, the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton invited him to the United States; he worked at Stanford University and at Yale before returning to Paris to teach at the École pratique des hautes études which became the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences.[3][5] He then co-founded in 1974 the Laboratoire Européen de Psychologie Sociale ("European Laboratory of Social Psychology") there.[9] He served as a visiting professor at the New School in New York City, at the Rousseau Institute in Geneva, as well as at the Université catholique de Louvain and at the University of Cambridge.[5]

By 1968, together with Brice Lalonde and others, he became involved in green politics, and ran in elections for the office of Mayor of Paris for what later became Les Verts.[4]

He died in Paris in 2014 at the age of 89.[10]

Research

[edit]His research focus was on group psychology and he began his career by investigating the way knowledge is reformulated as groups take hold of it, distorting it from its original form. His theory of social representations is now widespread in understanding this process of cultural Chinese whispers. Influenced by Gabriel Tarde, he later criticized American research into majority influence (conformity) and instead investigated the effects of minority influence, where the opinions of a small group influence those of a larger one.[3] He also researched the dynamics of group decisions and consensus-forming.

Social representations

[edit]Moscovici developed the theory of social representations which he defined as:

"a system of values, ideas and practices with a twofold function: first to establish an order which will enable individuals to orient themselves in their material and social world and to master it; and secondly to enable communication to take place among the members of a community by providing them with a code for social exchange and a code for naming and classifying unambiguously the various aspects of their world and their individual and group history".[11]

Minority influence

[edit]Moscovici claimed that majority influence in many ways was misleading – if the majority was indeed all-powerful, we would all end up thinking the same.[3] Drawing attention to the works of Gabriel Tarde, he pointed to the fact that most major social movements have been started by individuals and small groups (e.g. Christianity, Buddhism, the Suffragette movement, Nazism, etc.) and that without an outspoken minority, we would have no innovation or social change.

The study he is most famous for, Influences of a consistent minority on the responses of a majority in a colour perception task, is now seen as one of the defining investigations into the effects of minority influence:

- Aims: To investigate the process of innovation by looking at how a consistent minority affect the opinions of a larger group, possibly creating doubt and leading them to question and alter their views

- Procedures: Participants were first given an eye test to check that they were not colour blind. They were then placed in a group of four participants and two confederates. they were all shown 36 slides that were different shades of blue and asked to state the colour out loud. There were two groups in the experiment. In the first group the confederates were consistent and answered green for every slide. In the second group the confederates were inconsistent and answered green 24 times and blue 12 times.

- Findings: For 8.42% of the trials, participants agreed with the minority and said that the slides were green. Overall, 32% of the participants agreed at least once.

- Conclusions: The study suggested that minorities can indeed exert an effect over the opinion of a majority. Not to the same degree as majority influence, but the fact that almost a third of people agreed at least once is significant. However, this also leaves two thirds who never agreed. In a follow-up experiment, Moscovici demonstrated that consistency was the key factor in minority influence; by instructing the stooges to be inconsistent, the effect fell off sharply.

Works

[edit]Social psychology

[edit]- Le scandale de la pensée sociale (edited by Nikos Kalampalikis). Editions de l'EHESS, 2013

- Raison et cultures (edited by Nikos Kalampalikis). Editions de l'EHESS, 2012

- The Making of Modern Social Psychology: The Hidden Story of How an International Social Science was Created (with Ivana Markova). Polity Press, 2006.

- Social Representations: Explorations in Social Psychology (edited by Gerard Duveen), Polity Press, 2000

- Conflict and Consensus: General Theory of Collective Decisions (with Willem Doise; trans W.D.Hall) SAGE Publications, 1994

- La Machine à faire les dieux, Fayard, 1988 / The invention of society: psychological explanations for social phenomena, Cambridge, Polity Press, 1993

- Changing conceptions of conspiracy (with C.F. Graumann), New York: Springer, 1987

- L'Age des foules: un traité historique de psychologie des masses, Fayard, 1981 / The age of the crowd: a historical treatise on mass psychology. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1985

- Psychologie des minorités actives, Presses Universitaires de France, 1979

- Social influence and social change, Academic Press, 1976

- L’expérience du mouvement. Jean-Baptiste Baliani, disciple et critique de Galilée, Éditions Hermann, 1967

- Reconversion industrielle et changements sociaux. Un exemple: la chapellerie dans l'Aude, Armand Colin, 1961

- La psychanalyse, son image et son public, PUF, 1961/ new edition 1976 / Psychoanalysis. Its image, its public, Polity Press, 2008

Ecology

[edit]- De la Nature. Pour penser l'écologie, Métailié, 2002

- Réenchanter la nature (Interviews with Pascal Dibie), Aube, 2002

- Hommes domestiques et hommes sauvages, Union Générale d’éditions, 1974

- La société contre nature, UGE-Seuil, 1972 / Society against nature: the emergence of human societies. Hassocks, Harvester Press - Atlantic Highlands, N.J., Humanities Press, 1976

- Essai sur l’histoire humaine de la nature, Groupe Flammarion, 1968/1977

Autobiographies

[edit]- Mon après-guerre à Paris: Chronique des années retrouvées (Texte établi, présenté et annoté par Alexandra Laignel-Lavastine) Grasset, 2019

- Chronique des années égarées: récit autobiographique, Stock, 1997 / Cronica anilor risipiţi Romanian, Polirom, 1999

Honours and legacy

[edit]Honorary degrees

[edit]- University of Geneva; University of Glasgow; University of Sussex; University of Seville; University of Brussels; University of Bologna; University of London; University of Rome; University of Mexico; University of Pecs; University of Lisbon; Jönköping University; University of Iasi; (rejected)[12] University of Brasília; University of Buenos Aires; University of Evora[13]

International awards

[edit]- 1980 - In Media Res Prize of the Felix Burda Foundation

- 1988 - European Amalfi Prize for Sociology and Social Sciences for La Machine à faire les dieux

- 2000 - Ecologia Award

- 2003 - Balzan Prize[3]

- 2007 - Wilhelm Wundt-William James Award by the American Psychological Foundation and the European Federation of Psychologists' Associations[14]

- 2010 - Premio Nonino "Maestro del nostro tempo" ("Master of our Time")[15]

National awards

[edit]Prizes

[edit]In commemoration of his elaborate and significant contribution to the world of psychology and society in general, several awards, medals, lectures have been established. Notable among these are:

- Serge Moscovici Medal awarded by the European Association of Social Psychology (EASP)[16]

- "Serge Moscovici" Values-Based Leadership Award by the Aspen Institute Romania.[17]

Network

[edit]A network has been established to continue his work:

- Réseau Mondial Serge Moscovici[18]

Further reading

[edit]- Bonnes, M. (ed.), Moscovici, La Vita, il percorso intellettuale, i temi, le opere, Milano, FrancoAngeli, 1999.

- Fabrice Buschini, Nikos Kalampalikis (eds.), Penser la vie, le social, la nature. Mélanges en l'honneur de Serge Moscovici, Paris, Editions de la Maison des sciences de l'homme, 2001.

- Kalampaliki, N., Jodelet, D., Wieviorka, Moscovici, D., & Moscovici, P. (eds.). Serge Moscovici. Un regard sur les mondes communs, Paris: Editions de la Maison des sciences de l'homme, 2019.

- Papastamou, S., & Moliner, P. (eds.), Serge Moscovici's work. Legacy and perspective, Paris: Editions des archives contemporaines, 2021.

External links

[edit]- (in English and French) European Laboratory of Social Psychology website

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Augusto, Polmonari (2015). "Serge Moscovici". European Bulletin of Social Psychology. 27 (1): 15–22.

- ^ "Serge Moscovici, figure de la psychologie sociale, est mort". Le Monde.fr. November 16, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "2003 Balzan Prize for Social Psychology". Fondazione Internazionale Premio Balzan (International Balzan Prize Foundation). Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m (in Romanian) Lavinia Betea, "Moscovici, victima regimului Antonescu" Archived 2013-09-28 at the Wayback Machine, in Jurnalul Naţional, October 24, 2004 (retrieved June 17, 2007)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i (in French) Serge Moscovici. Repères bio-bibliographiques Archived 2007-08-04 at the Wayback Machine, at the Institut de Psychologie (retrieved June 17, 2007)

- ^ (in Romanian) Ştefan Ionescu, În umbra morţii. Memoria supravieţuitorilor Holocaustului în România, at Idee Communication Archived 2012-02-06 at the Wayback Machine (retrieved June 17, 2007)

- ^ a b (in Romanian) Isaac Chiva, "Pogromul de la Iaşi", in Observator Cultural (retrieved June 17, 2007)

- ^ Moscovici, Serge (2019). Mon apres-guerre a Paris. Paris: Grasset. p. 377. ISBN 9782246820727.

- ^ Moscovici, Serge. "Disparition de Jean-Claude AbricRIC". ADRIPS.org. Retrieved July 1, 2024.

- ^ Perez, Juan; Kalampalikis, Nikos; Lahlou, Saadi; Jodelet, Denise; Apostolidis, Thémis (2015). "In memoriam Serge Moscovici (1925-2014)". Bulletin de psychologie, Groupe d'étude de psychologie. 68 (2).

- ^ Moscovici, Serge (1968–1973). "Foreword". In Claudine Herzlich (ed.). Health and Illness - A social psychological analysis. London: Academic Press. pp. ix–xiv. ISBN 0123441501.

- ^ "Tatal raportorului Moscovici a fost terorizat de Brucan". March 25, 2005.

- ^ REMOSCO (2015). "In memoriam: Serge Moscovici (1925-2014)". European Bulletin of Social Psychology. 27 (1): 3–14.

- ^ "Wilhelm Wundt-William James Award". European Federation of Psychologists' Associations. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "Serge Moscovici". Premio Nonino. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ "Serge Moscovici Medal". European Association of Social Psychology. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- ^ ""Serge Moscovici" Leadership Award". Aspen Institute Romania. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- ^ "Réseau Mondial Serge Moscovici". Réseau Mondial Serge Moscovici. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

- 1925 births

- 2014 deaths

- Romanian Jews

- Romanian magazine editors

- Romanian magazine founders

- 20th-century French memoirists

- French political writers

- 20th-century French psychologists

- People from Brăila

- Political philosophers

- Romanian communists

- Romanian emigrants to France

- French people of Romanian-Jewish descent

- Social psychologists

- University of Paris alumni

- Academic staff of the University of Paris

- Foreign members of the Russian Academy of Education

- Commanders of the Legion of Honour

- The Greens (France) politicians

- French sociologists

- Members of the European Academy of Sciences and Arts

- French male writers

- Forced labourers under German rule during World War II