Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

| |

| Class identifiers | |

| Use | major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders |

| ATC code | N06AB |

| Biological target | Serotonin transporter |

| Clinical data | |

| Drugs.com | Drug Classes |

| Consumer Reports | Best Buy Drugs |

| External links | |

| MeSH | D017367 |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors or serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitor[1] (SSRIs) are a class of compounds typically used as antidepressants in the treatment of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders.

SSRIs are believed to increase the extracellular level of the neurotransmitter serotonin by inhibiting its reuptake into the presynaptic cell, increasing the level of serotonin in the synaptic cleft available to bind to the postsynaptic receptor. They have varying degrees of selectivity for the other monoamine transporters, with pure SSRIs having only weak affinity for the noradrenaline and dopamine transporter.

SSRIs are the first class of psychotropic drugs discovered using the process called rational drug design, a process that starts with a specific biological target and then creates a molecule designed to affect it.[2] They are the most widely prescribed antidepressants in many countries.[2] The efficacy of SSRIs in mild or moderate cases of depression has been disputed.[3][4][5]

Medical uses

The main indication for SSRIs is major depressive disorder (also called "major depression", "clinical depression" and often simply "depression"). SSRIs are frequently prescribed for anxiety disorders, such as social anxiety disorder, panic disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), eating disorders, chronic pain and occasionally, for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). They are also frequently used to treat depersonalization disorder, although generally with poor results.[6]

Depression

Antidepressants are recommended by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) as a first-line treatment of severe depression and for the treatment of mild-to-moderate depression that persists after conservative measures such as cognitive therapy.[7] They recommend against their routine use in those who have chronic health problems and mild depression.[7]

There has been controversy regarding the efficacy of antidepressants in treating depression depending on its severity and duration.

- Two meta-analyses published in 2008 (Kirsch) and 2010 (Fournier) found that in mild and moderate depression, the effect of SSRIs is small or none compared to placebo, while in very severe depression the effect of SSRIs is between "relatively small " and "substantial".[3][8] The 2008 meta-analysis combined 35 clinical trials submitted to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) before licensing of four newer antidepressants (including the SSRIs paroxetine and fluoxetine, the non-SSRI antidepressant nefazodone, and the serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine. The authors attributed the relationship between severity and efficacy to a reduction of the placebo effect in severely depressed patients, rather than an increase in the effect of the medication.[8] Some researchers have questioned the statistical basis of this study suggesting that it underestimates the effect size of antidepressants.[9][10]

- A 2010 comprehensive review conducted by NICE concluded that antidepressants have no advantage over placebo in the treatment of short term mild depression, but that the available evidence supported the use of antidepressants in the treatment of dysthymia and other forms of chronic mild depression.[11]

- A 2012 meta-analysis of the SSRIs fluoxetine and venlafaxine concluded that statistically and clinically significant treatment effects were observed for each drug relative to placebo irrespective of baseline depression severity.[12]

- In 2014 the U.S. FDA published a systematic review of all antidepressant maintenance trials submitted to the agency between 1985 and 2012. The authors concluded that maintenance treatment reduced the risk of relapse by 52% compared to placebo, and that this effect was primarily due to recurrent depression in the placebo group rather than a drug withdrawal effect.[13]

- A study examining publication of results from FDA-evaluated antidepressants concluded that those with favorable results were much more likely to be published than those with negative results.[14]

There does not appear to be a big difference in the effectiveness among the second generation antidepressants (SSRIs and SNRIs).[15]

In children there are concerns around the quality of the evidence on the meaningfulness of benefits seen.[16] If a medication is used, fluoxetine appears to be first line.[16]

Generalized anxiety disorder

SSRIs are recommended by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) that has failed to respond to conservative measures such as education and self-help activities. GAD is a common disorder of which the central feature is excessive worry about a number of different events. Key symptoms include excessive anxiety about multiple events and issues, and difficulty controlling worrisome thoughts that persists for at least 6 months.

Antidepressants provide a modest-to-moderate reduction in anxiety in GAD,[17] and are superior to placebo in treating GAD.[18] The efficacy of different antidepressants is similar.[17][18]

Obsessive compulsive disorder

SSRIs are a second line treatment of adult obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) with mild functional impairment and as first line treatment for those with moderate or severe impairment. In children, SSRIs can be considered as a second line therapy in those with moderate-to-severe impairment, with close monitoring for psychiatric adverse effects.[19] SSRIs are efficacious in the treatment of OCD; patients treated with SSRIs are about twice as likely to respond to treatment as those treated with placebo.[20][21]

Eating disorders

Anti-depressants are recommended as an alternative or additional first step to self-help programs in the treatment of bulimia nervosa.[17] SSRIs (fluoxetine in particular) are preferred over other anti-depressants due to their acceptability, tolerability, and superior reduction of symptoms in short term trials. Long term efficacy remains poorly characterized.

Similar recommendations apply to binge eating disorder.[17] SSRIs provide short term reductions in binge eating behavior, but have not been associated with significant weight loss.[22]

Clinical trials have generated mostly negative results for the use of SSRI's in the treatment of anorexia nervosa.[23] Treatment guidelines from the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence[17] recommend against the use of SSRIs in this disorder. Those from the American Psychiatric Association note that SSRIs confer no advantage regarding weight gain, but that they may be used for the treatment of co-existing depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders.[22]

Stroke recovery

SSRIs have been used in the treatment of stroke patients, including those with and without symptoms of depression. A recent meta analysis of randomized, controlled clinical trials found a statistically significant effect of SSRIs on dependence, neurological deficit, depression, and anxiety. There was no statistically significant effect on death, motor deficits, or cognition.[24]

Premature ejaculation

SSRIs are effective for the treatment of premature ejaculation. Chronic administration is more efficacious than on demand use.[25]

Adverse effects

Side effects vary among the individual drugs of this class. However certain types of adverse effects are found broadly among most if not all members of this class:

- increased risk of bone fractures by 1.7 fold[26]

- akathisia[27][28][29][30]

- suicidal ideation (thoughts of suicide) (see below)

- photosensitivity[31]

Sexual dysfunction

SSRIs can cause various types of sexual dysfunction such as anorgasmia, erectile dysfunction, diminished libido, genital numbness, and sexual anhedonia (pleasureless orgasm).[32] Initial studies found the incidence of sexual side effects from SSRIs not significantly different from placebo, but since these studies relied on unprompted reporting, the frequency was underestimated. In more recent studies, doctors have specifically asked about sexual difficulties, and found that they are present in most patients.[33][34]

Sexual dysfunction occasionally persists after discontinuing SSRIs. The frequency with which this happens is unknown.[35]

The mechanism by which SSRIs cause sexual side effects is not well understood. In part, it is thought that stimulation of postsynaptic 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors decreases dopamine and norepinephrine release from the substantia nigra. A number of (non-SSRI) drugs are not associated with sexual side effects (such as bupropion, mirtazapine, tianeptine, agomelatine and moclobemide.[36][37]

There is no FDA-approved treatment for SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction and there has been a lack of randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind studies of potential treatments. There is evidence for the following management strategies: for erectile dysfunction, the addition of a PDE5 inhibitor such as sildenafil; for decreased libido, possibly adding or switching to bupropion; and for overall sexual dysfunction, switching to nefazodone.[38]

Several small studies have suggested that SSRIs may adversely affect semen quality.[39]

Cardiac

SSRIs do not appear to affect the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) in those without a previous diagnosis of CHD.[40] A large cohort study suggested no substantial increase in the risk of cardiac malformations attributable to SSRI usage during the first trimester of pregnancy.[41] A number of large studies of people without known pre-existing heart disease have reported no EKG changes related to SSRI use.[42] The recommended maximum daily dose of citalopram and escitalopram was reduced due to concerns with QT interval prolongation.[43][44][45] In overdose, fluoxetine has been reported to cause sinus tachycardia, myocardial infarction, junctional rhythms and trigeminy. Some authors have suggested electrocardiographic monitoring in patients with severe pre-existing cardiovascular disease who are taking SSRI's.[46]

Bleeding

SSRIs interact with anticoagulants, like Warfarin and Aspirin.[47][48][49][50] This includes an increased risk of GI bleeding, and post operative bleeding.[47] The relative risk of intracranial bleeding is increased, but the absolute risk is very low.[51] SSRIs are known to cause platelet dysfunction.[52][53] This risk is greater in those who are also on anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents and NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), as well as with the co-existence of underlying diseases such as cirrhosis of the liver or liver failure.[54][55]

Discontinuation syndrome

Serotonin reuptake inhibitors should not be abruptly discontinued after extended therapy, and whenever possible, should be tapered over several weeks to minimize discontinuation-related symptoms which may include nausea, headache, dizziness, chills, body aches, paresthesias, insomnia, and electric shock-like sensations. Paroxetine may produce discontinuation-related symptoms at a greater rate than other SSRIs, though qualitatively similar effects have been reported for all SSRIs.[56][57] Discontinuation effects appear to be less for fluoxetine, perhaps owing to its long half-life and the natural tapering effect associated with its slow clearance from the body. One strategy for minimizing SSRI discontinuation symptoms is to switch the patient to fluoxetine and then taper and discontinue the fluoxetine.[56]

Suicide risk

Children and adolescents

Meta analyses of short duration randomized clinical trials have found that SSRI use is related to a higher risk of suicidal behavior in children and adolescents.[58][59][60] For instance, a 2004 U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) analysis of clinical trials on children with major depressive disorder found statistically significant increases of the risks of "possible suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior" by about 80%, and of agitation and hostility by about 130%;[61] According to the FDA, the heightened risk of suicidality is within the first one to two months of treatment.[62][63][64] The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) places the excess risk in the "early stages of treatment".[65] The European Psychiatric Association places the excess risk in the first two weeks of treatment and, based on a combination of epidemiological, prospective cohort, medical claims, and randomized clinical trial data, concludes that a protective effect dominates after this early period. A 2012 Cochrane review found that at six to nine months, suicidal ideation remained higher in children treated with antidepressants compared to those treated with psychological therapy.[66]

A recent comparison of aggression and hostility occurring during treatment with fluoxetine to placebo in children and adolescents found that no significant difference between the fluoxetine group and a placebo group.[67] There is also evidence that higher rates of SSRI prescriptions are associated with lower rates of suicide in children, though since the evidence is correlational, the true nature of the relationship is unclear.[68]

In 2004, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in the United Kingdom judged fluoxetine (Prozac) to be the only antidepressant that offered a favorable risk-benefit ratio in children with depression, though it was also associated with a slight increase in the risk of self-harm and suicidal ideation.[69] Only two SSRIs are licensed for use with children in the UK, sertraline (Zoloft) and fluvoxamine (Luvox), and only for the treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder. Fluoxetine is not licensed for this use.[70]

Adults

It is unclear whether or not SSRIs affect the risk of suicidal behavior for adults.

- A 2005 meta-analysis of drug company data found no evidence that SSRIs increased the risk of suicide; however, important protective or hazardous effects could not be excluded.[71]

- A 2005 review observed that suicide attempts are increased in those who use SSRIs as compared to placebo and compared to therapeutic interventions other than tricyclic antidepressants. No difference risk of suicide attempts was detected between SSRIs versus tricyclic antidepressants.[72]

- On the other hand, a 2006 review suggests that the widespread use of antidepressants in the new "SSRI-era" appear to have led to highly significant decline in suicide rates in most countries with traditionally high baseline suicide rates. The decline is particularly striking for women who, compared with men, seek more help for depression. Recent clinical data on large samples in the US too have revealed a protective effect of antidepressant against suicide.[73]

- A 2006 meta analysis of random controlled trials suggests that SSRIs increase suicide ideation compared with placebo. However, the observational studies suggests that SSRIs did not increase suicide risk more than older antidepressants. The researchers stated that if SSRIs increase suicide risk in some patients, the number of additional deaths is very small because ecological studies have generally found that suicide mortality has declined (or at least not increased) as SSRI use has increased.[74]

- An additional meta-analysis by the FDA in 2006 found an age-related effect of SSRI's. Among adults younger than 25 years, results indicated that there was a higher risk for suicidal behavior. For adults between 25 and 64, the effect appears neutral on suicidal behavior but possibly protective for suicidal behavior for adults between the ages of 25 and 64. For adults older than 64, SSRI's seem to reduce the risk of both suicidal behavior.[58]

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

SSRI use in pregnancy has been associated with a variety of risks with varying degrees of proof of causation. As depression is independently associated with negative pregnancy outcomes, determining the extent to which observed associations between antidepressant use and specific adverse outcomes reflects a causative relationship has been difficult in some cases.[75] In other cases, the attribution of adverse outcomes to antidepressant exposure seems fairly clear.

SSRI use in pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of spontaneous abortion of about 1.7-fold.[76][77]

A systematic review of the risk of major birth defects in antidepressant-exposed pregnancies found a small increase (3% to 24%) in the risk of major malformations and a risk of cardiovascular birth defects that did not differ from non-exposed pregnancies.[78] A study of fluoxetine-exposed pregnancies found a 12% increase in the risk of major malformations that just missed statistical significance.[79] Other studies have found an increased risk of cardiovascular birth defects among depressed mothers not undergoing SSRI treatment, suggesting the possibility of ascertainment bias, e.g. that worried mothers may pursue more aggressive testing of their infants.[80] Another study found no increase in cardiovascular birth defects and a 27% increased risk of major malformations in SSRI exposed pregnancies.[77]

The FDA issued a statement on July 19, 2006 stating nursing mothers on SSRIs must discuss treatment with their physicians. However, the medical literature on the safety of SSRIs has determined that some SSRIs like Sertraline and Paroxetine are considered safe for breastfeeding.[81][82][83]

Maternal SSRI use may be associated with autism.[84] A large cohort study published 2013 found no significant association between SSRI use and autism in offspring.[85]

Neonatal abstinence syndrome

Several studies have documented Neonatal abstinence syndrome, a syndrome of neurological, gastrointestinal, autonomic, endocrine and/or respiratory symptoms among a large minority of infants with intrautarine exposure. These syndromes are short-lived, but insufficient long term data is available to determine whether there are long term effects.[86][87]

Persistent pulmonary hypertension

Persistent pulmonary hypertension (PPHN) is a serious and life-threatening, but very rare, lung condition that occurs soon after birth of the newborn. Newborn babies with PPHN have high pressure in their lung blood vessels and are not able to get enough oxygen into their bloodstream. About 1 to 2 babies per 1000 babies born in the U.S. develop PPHN shortly after birth, and often they need intensive medical care. It is associated with about a 25% risk of significant long term neurological deficits.[88] A 2014 meta analysis found no increased risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension associated with exposure to SSRI's in early pregnancy and a slight increase in risk associates with exposure late in pregnancy; "an estimated 286 to 351 women would need to be treated with an SSRI in late pregnancy to result in an average of one additional case of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn.".[89] A review published in 2012 reached conclusions very similar to those of the 2014 study.[90]

Overdose

SSRIs appear safer in overdose when compared with traditional antidepressants, such as the tricyclic antidepressants. This relative safety is supported both by case series and studies of deaths per numbers of prescriptions.[91] However, case reports of SSRI poisoning have indicated that severe toxicity can occur[92] and deaths have been reported following massive single ingestions,[93] although this is exceedingly uncommon when compared to the tricyclic antidepressants.[91]

Because of the wide therapeutic index of the SSRIs, most patients will have mild or no symptoms following moderate overdoses. The most commonly reported severe effect following SSRI overdose is serotonin syndrome; serotonin toxicity is usually associated with very high overdoses or multiple drug ingestion.[94] Other reported significant effects include coma, seizures, and cardiac toxicity.[91]

The SSRIs, in decreasing toxicity in overdose, can be listed as follows:[95]

- Citalopram (due to the potential for QT interval prolongation)

- Fluvoxamine

- Escitalopram

- Paroxetine

- Sertraline

- Fluoxetine

Contraindications and drug interactions

The following drugs may precipitate serotonin syndrome in people on SSRIs:[96][97]

- linezolid

- methylene blue dye

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) including moclobemide, phenelzine, tranylcypromine, selegiline and methylene blue

- Lithium

- Sibutramine

- MDMA (ecstasy)

- Dextromethorphan

- Tramadol

- Pethidine/meperidine

- St. John's wort

- Yohimbe

- Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs)

- Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)

- Buspirone

- Triptan

- Mirtazapine

Painkillers of the NSAIDs drug family may interfere and reduce efficiency of SSRIs and may compound the increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeds caused by SSRI use.[48][50][98] NSAIDs include:

There are a number of potential pharmacokinetic interactions between the various individual SSRIs and other medications. Most of these arise from the fact that every SSRI has the ability to inhibit certain P450 cytochromes.[99][100]

| Drug Name | CYP1A2 | CYP2C9 | CYP2C19 | CYP2D6 | CYP3A4 | CYP2B6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citalopram | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 |

| Escitalopram | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 |

| Fluoxetine | + | ++ | +/++ | +++ | + | + |

| Fluvoxamine | +++ | ++ | +++ | + | + | + |

| Paroxetine | + | + | + | +++ | + | +++ |

| Sertraline | + | + | +/++ | + | + | + |

Legend:

0 — no inhibition.

+ — mild inhibition.

++ — moderate inhibition.

+++ — strong inhibition.

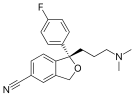

List of agents

Drugs in this class include (trade names in parentheses):

- citalopram (Celexa, Cipramil, Cipram, Dalsan, Recital, Emocal, Sepram, Seropram, Citox, Cital)

- dapoxetine (Priligy)

- escitalopram (Lexapro, Cipralex, Seroplex, Esertia)

- fluoxetine (Depex, Prozac, Fontex, Seromex, Seronil, Sarafem, Ladose, Motivest, Flutop, Fluctin (EUR), Fluox (NZ), Depress (UZB), Lovan (AUS), Prodep (IND))

- fluvoxamine (Luvox, Fevarin, Faverin, Dumyrox, Favoxil, Movox, Floxyfral)

- indalpine (Upstene) (discontinued)

- paroxetine (Paxil, Seroxat, Sereupin, Aropax, Deroxat, Divarius, Rexetin, Xetanor, Paroxat, Loxamine, Deparoc)

- sertraline (Zoloft, Lustral, Serlain, Asentra, Tresleen)

- zimelidine (Zelmid, Normud) (discontinued)

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

File:Paroxetine.svg |

|

|

|

Related agents

SSRIs form a subclass of serotonin uptake inhibitors, which includes other non-selective inhibitors as well. The serotonergic Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors are also commonly used as antidepressants.

Mechanism of action

In the brain, messages are passed between two nerve cells via a chemical synapse, a small gap between the cells. The (presynaptic) cell that sends the information releases neurotransmitters (including serotonin) into that gap. The neurotransmitters are then recognized by receptors on the surface of the recipient (postsynaptic) cell, which upon this stimulation, in turn, relays the signal. About 10% of the neurotransmitters are lost in this process; the other 90% are released from the receptors and taken up again by monoamine transporters into the sending (presynaptic) cell (a process called reuptake).

SSRIs inhibit the reuptake of serotonin. As a result, the serotonin stays in the synaptic gap longer than it normally would, and may repeatedly stimulate the receptors of the recipient cell. In the short run this leads to an increase in signalling across synapses in which serotonin serves as the primary neurotransmitter. On chronic dosing, the increased occupancy of pre-synaptic serotonin receptors signals the pre-synaptic neuron to synthesize and release less serotonin. Serotonin levels within the synapse drop, then rise again, ultimately leading to down-regulation of post-synaptic serotonin receptors.[101] Other, indirect effects may include increased norepinephrine output, increased neuronal cyclic AMP levels, and increased levels of regulatory factors such as BDNF and CREB.[102] Owing to the lack of a widely accepted comprehensive theory of the biology of mood disorders, there is no widely accepted theory of how these changes lead to the mood-elevating and anti-anxiety effects of SSRIs.

Pharmacogenetics

Large bodies of research are devoted to using genetic markers to predict whether patients will respond to SSRIs or have side effects that will cause their discontinuation, although these tests are not yet ready for widespread clinical use.[103] Single-nucleotide polymorphisms of the 5-HT(2A) gene correlated with paroxetine discontinuation due to side effects in a group of elderly patients with major depression, but not mirtazapine (a non-SSRI antidepressant) discontinuation.[104]

SSRIs versus TCAs

SSRIs are described as 'selective' because they affect only the reuptake pumps responsible for serotonin, as opposed to earlier antidepressants, which affect other monoamine neurotransmitters as well, and as a result, SSRIs have fewer side effects.

There appears no significant difference in effectiveness between SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants, which were the most commonly used class of antidepressants before the development of SSRIs.[105] However, SSRIs have the important advantage that their toxic dose is high, and, therefore, they are much more difficult to use as a means to commit suicide. Further, they have fewer and milder side effects. Tricyclic antidepressant also have a higher risk of serious cardiovascular side effects, which SSRIs lack.

SSRIs act on signal pathways such as cAMP (Cyclic AMP) on the postsynaptic neuronal cell, which leads to the release of Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF). BDNF enhances the growth and survival of cortical neurons and synapses.[102]

Society and culture

Controversy

David Healy has argued that warning signs were available for many years prior to regulatory authorities moving to put warnings on antidepressant labels that they might cause suicidal thoughts.[106] At the time these warnings were added, others argued that the evidence for harm remained unpersuasive[107][108] and others continued to do so after the warnings were added.[109][110]

See also

- Dopamine reuptake inhibitor (DRI)

- Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (NaSSA)

- Norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI)

- Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (NRI)

- Serotonin-norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor (SNDRI)

- Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI)

- Serotonin releasing agent (SRA)

- Serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI)

- Trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1)

References

- ^ Barlow, David H. Durand, V. Mark (2009). "Chapter 7: Mood Disorders and Suicide". Abnormal Psychology: An Integrative Approach (Fifth ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. p. 239. ISBN 0-495-09556-7. OCLC 192055408.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Preskorn SH, Ross R, Stanga CY (2004). "Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors". In Sheldon H. Preskorn, Hohn P. Feighner, Christina Y. Stanga and Ruth Ross (ed.). Antidepressants: Past, Present and Future. Berlin: Springer. pp. 241–62. ISBN 978-3-540-43054-4.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Dimidjian S, Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC, Fawcett J (January 2010). "Antidepressant Drug Effects and Depression Severity". JAMA : The Journal of the American Medical Association. 303 (1): 47–53. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1943. PMC 3712503. PMID 20051569.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kramer, Peter (7 Sep 2011). "In Defense of Antidepressants". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ Pies R (April 2010). "Antidepressants Work, Sort of-Our System of Care Does Not". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 30 (2): 101–104. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181d52dea. PMID 20520282.

- ^ Medford, Nick. "Understanding and treating depersonalization disorder". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment (2005). Retrieved 2011-11-11.

- ^ a b "www.nice.org.uk" (PDF).

- ^ a b Kirsch I, Deacon BJ, Huedo-Medina TB, Scoboria A, Moore TJ, Johnson BT (February 2008). "Initial Severity and Antidepressant Benefits: A Meta-Analysis of Data Submitted to the Food and Drug Administration". PLoS Medicine. 5 (2): e45. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050045. PMC 2253608. PMID 18303940.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Horder J, Matthews P, Waldmann R (June 2010). "Placebo, Prozac and PLoS: significant lessons for psychopharmacology". Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England). 25 (10): 1277–88. doi:10.1177/0269881110372544. PMID 20571143.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fountoulakis KN, Möller HJ (August 2010). "Efficacy of antidepressants: a re-analysis and re-interpretation of the Kirsch data". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology / Official Scientific Journal of the Collegium Internationale Neuropsychopharmacologicum (CINP). 14 (3): 1–8. doi:10.1017/S1461145710000957. PMID 20800012.

- ^ Depression: The NICE Guideline on the Treatment and Management of Depression in Adults (Updated Edition) (PDF). RCPsych Publications. 2010. ISBN 1-904671-85-3.

- ^ Gibbons RD, Hur K, Brown CH, Davis JM, Mann JJ (June 2012). "Benefits from antidepressants: synthesis of 6-week patient-level outcomes from double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trials of fluoxetine and venlafaxine". Archives of General Psychiatry. 69 (6): 572–9. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2044. PMC 3371295. PMID 22393205.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD; et al. (January 2010). "Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis". JAMA. 303 (1): 47–53. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1943. PMC 3712503. PMID 20051569.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Turner EH, Matthews AM, Linardatos E, Tell RA, Rosenthal R (January 2008). "Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy". The New England Journal of Medicine. 358 (3): 252–60. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa065779. PMID 18199864.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Morgan LC, Thaler K, Lux L, Van Noord M, Mager U, Thieda P, Gaynes BN, Wilkins T, Strobelberger M, Lloyd S, Reichenpfader U, Lohr KN (December 2011). "Comparative benefits and harms of second-generation antidepressants for treating major depressive disorder: an updated meta-analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 155 (11): 772–85. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-155-11-201112060-00009. PMID 22147715.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hetrick SE, McKenzie JE, Cox GR, Simmons MB, Merry SN (Nov 14, 2012). "Newer generation antidepressants for depressive disorders in children and adolescents". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11: CD004851. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004851.pub3. PMID 23152227.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e "www.nice.org.uk" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-02-20. Cite error: The named reference "urlwww.nice.org.uk" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Kapczinski F, Lima MS, Souza JS, Schmitt R (2003). Kapczinski, Flavio FK (ed.). "Antidepressants for generalized anxiety disorder". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD003592. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003592. PMID 12804478.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Obsessive-compulsive disorder: Core interventions in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorder" (PDF). November 2005

- ^ Arroll B, Elley CR, Fishman T, Goodyear-Smith FA, Kenealy T, Blashki G, Kerse N, Macgillivray S (2009). Arroll, Bruce (ed.). "Antidepressants versus placebo for depression in primary care". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD007954. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007954. PMID 19588448.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Medscape Log In". [dead link]

- ^ a b "National Guideline Clearinghouse | Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders".

- ^ Flament MF, Bissada H, Spettigue W (March 2012). "Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of eating disorders". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology / Official Scientific Journal of the Collegium Internationale Neuropsychopharmacologicum (CINP). 15 (2): 189–207. doi:10.1017/S1461145711000381. PMID 21414249.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mead GE, Hsieh CF, Lee R, Kutlubaev MA, Claxton A, Hankey GJ, Hackett ML (2012). Mead, Gillian E (ed.). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for stroke recovery". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11: CD009286. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009286.pub2. PMID 23152272.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Waldinger MD (November 2007). "Premature ejaculation: state of the art". The Urologic Clinics of North America. 34 (4): 591–9, vii–viii. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2007.08.011. PMID 17983899.

- ^ Wu Q, Bencaz AF, Hentz JG, Crowell MD (January 2012). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment and risk of fractures: a meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies". Osteoporosis International : A Journal Established as Result of Cooperation Between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 23 (1): 365–75. doi:10.1007/s00198-011-1778-8. PMID 21904950.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stahl SM, Lonnen AJ (2011). "The Mechanism of Drug-induced Akathsia". CNS Spectrums. PMID 21406165.

- ^ Lane RM (1998). "SSRI-induced extrapyramidal side-effects and akathisia: implications for treatment". Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England). 12 (2): 192–214. doi:10.1177/026988119801200212. PMID 9694033.

- ^ Koliscak LP, Makela EH (2009). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced akathisia". Journal of the American Pharmacists Association : JAPhA. 49 (2): e28–36, quiz e37–8. doi:10.1331/JAPhA.2009.08083. PMID 19289334.

- ^ Leo RJ (1996). "Movement disorders associated with the serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 57 (10): 449–54. doi:10.4088/JCP.v57n1002. PMID 8909330.

- ^ September 23, 2012. "SSRIs and Depression". Emedicinehealth.com. Retrieved 2012-09-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Bahrick, Audrey (2008). "Persistence of Sexual Dysfunction Side Effects after Discontinuation of Antidepressant Medications: Emerging Evidence" (PDF). The Open Psychology Journal. 1: 42–50. doi:10.2174/1874350100801010042. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ Montejo AL, Llorca G, Izquierdo JA, Rico-Villademoros F (2001). "Incidence of sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressant agents: a prospective multicenter study of 1022 outpatients. Spanish Working Group for the Study of Psychotropic-Related Sexual Dysfunction". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 62 Suppl 3: 10–21. PMID 11229449.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hu XH, Bull SA, Hunkeler EM, Ming E, Lee JY, Fireman B, Markson LE (2004). "Incidence and duration of side effects and those rated as bothersome with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment for depression: patient report versus physician estimate". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 65 (7): 959–65. doi:10.4088/JCP.v65n0712. PMID 15291685.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "www.accessdata.fda.gov" (PDF).

- ^ Clayton, Anita H. (2003). "Antidepressant-Associated Sexual Dysfunction: A Potentially Avoidable Therapeutic Challenge". Primary Psychiatry. 10 (1): 55–61.

- ^ Kanaly KA, Berman JR (December 2002). "Sexual side effects of SSRI medications: potential treatment strategies for SSRI-induced female sexual dysfunction". Current Women's Health Reports. 2 (6): 409–16. PMID 12429073.

- ^ Balon R (2006). "SSRI-Associated Sexual Dysfunction". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 163 (9): 1504–9, quiz 1664. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.9.1504. PMID 16946173.

- ^ Koyuncu H, Serefoglu EC, Ozdemir AT, Hellstrom WJ (September 2012). "Deleterious effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment on semen parameters in patients with lifelong premature ejaculation". Int. J. Impot. Res. 24 (5): 171–3. doi:10.1038/ijir.2012.12. PMID 22573230.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Oh, SW; Kim, J; Myung, SK; Hwang, SS; Yoon, DH (Mar 20, 2014). "Antidepressant Use and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease: Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 78 (4): 727–37. doi:10.1111/bcp.12383. PMID 24646010.

- ^ Huybrechts, Krista F.; Palmsten, Kristin; Avorn, Jerry; Cohen, Lee S.; Holmes, Lewis B.; Franklin, Jessica M.; Mogun, Helen; Levin, Raisa; Kowal, Mary; Setoguchi, Soko; Hernández-Díaz, Sonia (2014). "Antidepressant Use in Pregnancy and the Risk of Cardiac Defects". New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (25): 2397–2407. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1312828. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 24941178.

- ^ Goldberg RJ (1998). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: infrequent medical adverse effects". Archives of Family Medicine. 7 (1): 78–84. doi:10.1001/archfami.7.1.78. PMID 9443704.

- ^ FDA. "FDA Drug Safety".

- ^ Citalopram and escitalopram: QT interval prolongation—new maximum daily dose restrictions (including in elderly patients), contraindications, and warnings. From Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Article date: December 2011

- ^ "ref2" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-09-23.

- ^ Pacher, P; Ungvari, Z; Nanasi, PP; Furst, S; Kecskemeti, V (Jun 1999). "Speculations on difference between tricyclic and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants on their cardiac effects. Is there any?". Current medicinal chemistry. 6 (6): 469–80. PMID 10213794.

- ^ a b Weinrieb RM, Auriacombe M, Lynch KG, Lewis JD (March 2005). "Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors and the risk of bleeding". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 4 (2): 337–44. doi:10.1517/14740338.4.2.337. PMID 15794724.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Taylor, D; Carol, P; Shitij, K (2012). The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9780470979693.

- ^ Andrade C, Sandarsh S, Chethan KB, Nagesh KS (December 2010). "Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Antidepressants and Abnormal Bleeding: A Review for Clinicians and a Reconsideration of Mechanisms". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 71 (12): 1565–1575. doi:10.4088/JCP.09r05786blu. PMID 21190637.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b de Abajo FJ, García-Rodríguez LA (July 2008). "Risk of upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and venlafaxine therapy: interaction with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and effect of acid-suppressing agents". Archives of General Psychiatry. 65 (7): 795–803. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.79. PMID 18606952.

- ^ Hackam DG, Mrkobrada M (2012). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and brain hemorrhage: a meta-analysis". Neurology. 79 (18): 1862–5. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318271f848. PMID 23077009.

- ^ Serebruany VL (February 2006). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and increased bleeding risk: are we missing something?". The American Journal of Medicine. 119 (2): 113–6. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.03.044. PMID 16443409.

- ^ Halperin D, Reber G (2007). "Influence of antidepressants on hemostasis". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 9 (1): 47–59. PMC 3181838. PMID 17506225.

- ^ Andrade C, Sandarsh S, Chethan KB, Nagesh KS (2010). "Serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants and abnormal bleeding: a review for clinicians and a reconsideration of mechanisms". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 71 (12): 1565–75. doi:10.4088/JCP.09r05786blu. PMID 21190637.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ de Abajo, FJ (2011). "Effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on platelet function: mechanisms, clinical outcomes and implications for use in elderly patients". Drugs & Aging. 28 (5): 345–67. doi:10.2165/11589340-000000000-00000. PMID 21542658.

- ^ a b "PsychiatryOnline | APA Practice Guidelines | Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder, Third Edition".

- ^ Renoir T (2013). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant treatment discontinuation syndrome: a review of the clinical evidence and the possible mechanisms involved". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 4: 45. doi:10.3389/fphar.2013.00045. PMC 3627130. PMID 23596418.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Stone MB, Jones ML (2006-11-17). "Clinical review: relationship between antidepressant drugs and suicidal behavior in adults" (PDF). Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). FDA. pp. 11–74. Retrieved 2007-09-22. Cite error: The named reference "FDA2" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Levenson M, Holland C (2006-11-17). "Statistical Evaluation of Suicidality in Adults Treated with Antidepressants" (PDF). Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). FDA. pp. 75–140. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

- ^ Olfson M, Marcus SC, Shaffer D (August 2006). "Antidepressant drug therapy and suicide in severely depressed children and adults: A case-control study". Archives of General Psychiatry. 63 (8): 865–72. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.865. PMID 16894062.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hammad TA (2004-08-116). "Review and evaluation of clinical data. Relationship between psychiatric drugs and pediatric suicidal behavior" (PDF). FDA. pp. 42, 115. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Antidepressant Use in Children, Adolescents, and Adults".

- ^ "FDA Medication Guide for Antidepressants". Retrieved 2014-06-05.

- ^ Cox GR, Callahan P, Churchill R, Hunot V, Merry SN, Parker AG, Hetrick SE (2012). "Psychological therapies versus antidepressant medication, alone and in combination for depression in children and adolescents". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 11: CD008324. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008324.pub2. PMID 23152255.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "www.nice.org.uk" (PDF).

- ^ Cox GR, Callahan P, Churchill R; et al. (2012). "Psychological therapies versus antidepressant medication, alone and in combination for depression in children and adolescents". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 11: CD008324. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008324.pub2. PMID 23152255.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Meta-Analysis of Aggression and/or Hostility-Related Events in Children and Adolescents Treated with Fluoxetine Compared with Placebo Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. October 2007; 17(5) 713–718. doi:10.1089/cap.2006.0138.

- ^ Gibbons RD, Hur K, Bhaumik DK, Mann JJ (November 2006). "The relationship between antidepressant prescription rates and rate of early adolescent suicide". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 163 (11): 1898–904. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.11.1898. PMID 17074941.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Report of the CSM expert working group on the safety of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants" (PDF). MHRA. 2004-12-01. Retrieved 2007-09-25.

- ^ "Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs): Overview of regulatory status and CSM advice relating to major depressive disorder (MDD) in children and adolescents including a summary of available safety and efficacy data". MHRA. 2005-09-29. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ^ Gunnell D, Saperia J, Ashby D (February 2005). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and suicide in adults: meta-analysis of drug company data from placebo controlled, randomised controlled trials submitted to the MHRA's safety review". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 330 (7488): 385. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7488.385. PMC 549105. PMID 15718537.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fergusson D, Doucette S, Glass KC, Shapiro S, Healy D, Hebert P, Hutton B (February 2005). "Association between suicide attempts and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: systematic review of randomised controlled trials". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 330 (7488): 396. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7488.396. PMC 549110. PMID 15718539.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rihmer Z, Akiskal H (August 2006). "Do antidepressants t(h)reat(en) depressives? Toward a clinically judicious formulation of the antidepressant-suicidality FDA advisory in light of declining national suicide statistics from many countries". Journal of Affective Disorders. 94 (1–3): 3–13. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.04.003. PMID 16712945.

- ^ Hall WD, Lucke J (2006). "How have the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants affected suicide mortality?". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 40 (11–12): 941–50. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1614.2006.01917.x. PMID 17054562.

- ^ Malm H (December 2012). "Prenatal exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and infant outcome". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 34 (6): 607–14. doi:10.1097/FTD.0b013e31826d07ea. PMID 23042258.

- ^ Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M (2006). "Pregnancy outcomes following exposure to serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a meta-analysis of clinical trials". Reproductive Toxicology (Elmsford, N.Y.). 22 (4): 571–575. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2006.03.019. PMID 16720091.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Nikfar S, Rahimi R, Hendoiee N, Abdollahi M (2012). "Increasing the risk of spontaneous abortion and major malformations in newborns following use of serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy: A systematic review and updated meta-analysis". Daru : Journal of Faculty of Pharmacy, Tehran University of Medical Sciences. 20 (1): 75. doi:10.1186/2008-2231-20-75. PMC 3556001. PMID 23351929.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Einarson TR, Kennedy D, Einarson A (2012). "Do findings differ across research design? The case of antidepressant use in pregnancy and malformations". Journal of Population Therapeutics and Clinical Pharmacology = Journal De La Thérapeutique Des Populations Et De La Pharamcologie Clinique. 19 (2): e334–48. PMID 22946124.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Riggin L, Frankel Z, Moretti M, Pupco A, Koren G (April 2013). "The fetal safety of fluoxetine: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada : JOGC = Journal D'obstétrique Et Gynécologie Du Canada : JOGC. 35 (4): 362–9. PMID 23660045.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Koren G, Nordeng HM (February 2013). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and malformations: case closed?". Seminars in Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 18 (1): 19–22. doi:10.1016/j.siny.2012.10.004. PMID 23228547.

- ^ "Breastfeeding Update: SDCBC's quarterly newsletter". Breastfeeding.org. Retrieved 2010-07-10. [dead link]

- ^ "Using Antidepressants in Breastfeeding Mothers". kellymom.com. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ Gentile S, Rossi A, Bellantuono C (2007). "SSRIs during breastfeeding: spotlight on milk-to-plasma ratio". Archives of Women's Mental Health. 10 (2): 39–51. doi:10.1007/s00737-007-0173-0. PMID 17294355.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ USA (2012-05-24). "Antidepressant use during pregnancy and ... [Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011] – PubMed – NCBI". Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2012-09-23.

- ^ Hviid A, Melbye M, Pasternak B (19 December 2013). "Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy and risk of autism". The New England Journal of Medicine. 369 (25): 2406–2415. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1301449. PMID 24350950. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fenger-Grøn J, Thomsen M, Andersen KS, Nielsen RG (September 2011). "Paediatric outcomes following intrauterine exposure to serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a systematic review". Danish Medical Bulletin. 58 (9): A4303. PMID 21893008.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kieviet N, Dolman KM, Honig A (2013). "The use of psychotropic medication during pregnancy: how about the newborn?". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 9: 1257–1266. doi:10.2147/NDT.S36394. PMC 3770341. PMID 24039427.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Persistent Newborn Pulmonary Hypertension".

- ^ Grigoriadis S, Vonderporten EH, Mamisashvili L, Tomlinson G, Dennis CL, Koren G, Steiner M, Mousmanis P, Cheung A, Ross LE (2014). "Prenatal exposure to antidepressants and persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 348: f6932. doi:10.1136/bmj.f6932. PMC 3898424. PMID 24429387.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ 't Jong GW, Einarson T, Koren G, Einarson A (November 2012). "Antidepressant use in pregnancy and persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN): a systematic review". Reproductive Toxicology (Elmsford, N.Y.). 34 (3): 293–7. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2012.04.015. PMID 22564982.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Isbister GK, Bowe SJ, Dawson A, Whyte IM (2004). "Relative toxicity of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in overdose". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology. 42 (3): 277–85. doi:10.1081/CLT-120037428. PMID 15362595.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Borys DJ, Setzer SC, Ling LJ, Reisdorf JJ, Day LC, Krenzelok EP (1992). "Acute fluoxetine overdose: a report of 234 cases". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 10 (2): 115–20. doi:10.1016/0735-6757(92)90041-U. PMID 1586402.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Oström M, Eriksson A, Thorson J, Spigset O (1996). "Fatal overdose with citalopram". Lancet. 348 (9023): 339–40. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)64513-8. PMID 8709713.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sporer KA (1995). "The serotonin syndrome. Implicated drugs, pathophysiology and management". Drug Safety : An International Journal of Medical Toxicology and Drug Experience. 13 (2): 94–104. doi:10.2165/00002018-199513020-00004. PMID 7576268.

- ^ White N, Litovitz T, Clancy C (December 2008). "Suicidal antidepressant overdoses: a comparative analysis by antidepressant type" (PDF). Journal of Medical Toxicology : Official Journal of the American College of Medical Toxicology. 4 (4): 238–250. doi:10.1007/BF03161207. PMC 3550116. PMID 19031375.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ener RA, Meglathery SB, Van Decker WA, Gallagher RM (March 2003). "Serotonin Syndrome and Other Serotonergic Disorders". Pain Medicine (Malden, Mass.). 4 (1): 63–74. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03005.x. PMID 12873279.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Boyer EW, Shannon M; Shannon, M (2005). "The serotonin syndrome" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (11): 1112–1120. doi:10.1056/NEJMra041867. PMID 15784664.

- ^ Solomon H. Snyder. "J.L. Warner-Schmidt et.al "Antidepressant effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are attenuated by antiinflammatory drugs in mice and humans" PNAS 2011". Pnas.org. Retrieved 2012-09-23.

- ^ Brunton, L; Chabner, B; Knollman, B (2010). Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th ed.). McGraw Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0071624428.

- ^ Ciraulo, DA; Shader, RI (2011). Pharmacotherapy of Depression (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 49. doi:10.1007/978-1-60327-435-7. ISBN 978-1-60327-435-7.

- ^ Goodman, Louis S. (Louis Sanford); Brunton, Laurence L.; Chabner, Bruce.; Knollmann, Björn C. (2001). Goodman Gilman's pharmacological basis of therapeuti. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 459–461. ISBN 0-07-162442-2.

- ^ a b Kolb, Bryan and Wishaw Ian. An Introduction to Brain and Behavior. New York: Worth Publishers 2006, Print.

- ^ Rasmussen-Torvik LJ, McAlpine DD (2007). "Genetic screening for SSRI drug response among those with major depression: great promise and unseen perils". Depression and Anxiety. 24 (5): 350–7. doi:10.1002/da.20251. PMID 17096399.

- ^ Murphy GM, Kremer C, Rodrigues HE, Schatzberg AF (October 2003). "Pharmacogenetics of antidepressant medication intolerance". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 160 (10): 1830–5. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1830. PMID 14514498.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Anderson IM (April 2000). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus tricyclic antidepressants: a meta-analysis of efficacy and tolerability". Journal of Affective Disorders. 58 (1): 19–36. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(99)00092-0. PMID 10760555.

- ^ Healy D; Aldred G (2005). "Antidepressant drug use and the risk of suicide" (PDF). International Review of Psychiatry. 17: 163–172. doi:10.1080/09540260500071624.

- ^ Lapierre YD (September 2003). "Suicidality with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: Valid claim?". J Psychiatry Neurosci. 28 (5): 340–7. PMC 193980. PMID 14517577.

- ^ 12668373

- ^ Kaizar EE, Greenhouse JB, Seltman H, Kelleher K (2006). "Do antidepressants cause suicidality in children? A Bayesian meta-analysis". Clin Trials. 3 (2): 73–90, discussion 91–8. doi:10.1191/1740774506cn139oa. PMID 16773951.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gibbons RD, Brown CH, Hur K, Davis J, Mann JJ (June 2012). "Suicidal thoughts and behavior with antidepressant treatment: reanalysis of the randomized placebo-controlled studies of fluoxetine and venlafaxine". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 69 (6): 580–7. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2048. PMC 3367101. PMID 22309973.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- PROZAC Product/Prescribing Information at Eli Lilly and Company

- Serotonin+uptake+inhibitors at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)