Toggenburg War

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (August 2016) |

| Toggenburg War Second War of Villmergen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of European wars of religion | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Protestants |

Catholics | ||||||

The Toggenburg War, also known as the Second War of Villmergen[2] or the Swiss Civil War of 1712,[3] was a Swiss civil war during the Old Swiss Confederacy from 12 April to 11 August 1712. The Catholic "inner cantons" and the Imperial Abbey of Saint Gall fought the Protestant cantons of Bern and Zürich as well as the abbatial subjects of Toggenburg. The conflict was a religious war, a war for hegemony in the Confederacy and an uprising of subjects.[4] The war ended in a Protestant victory and upset the balance of political power within the Confederacy.

Background

[edit]The war was caused by a conflict between the prince-abbot of St Gall, Leodegar Bürgisser, and his Protestant subjects in the County of Toggenburg. It had belonged to the Imperial Abbey of St Gall since 1460 but was simultaneously connected to the Swiss Cantons of Glarus and Schwyz through Landrecht since 1436. After the Reformation, about two thirds of the Toggenburg population were Protestants, but they were not the majority in every municipality. After the transaction of sovereignty to the Imperial Abbey, the Reformed inhabitants of Toggenburg were promised by their Swiss allies of the Cantons of Zürich and Bern and by the prince-abbot that the principle of equal treatment in religious matters would be respected. However, the abbots of St Gall undertook attempts to return Toggenburg to Catholicism in the frame of the Counter-Reformation. In all municipalities, including those that were almost completely Reformed, the position of Catholics was strengthened, and new Catholic churches were built in several towns, which made the common usage of parish churches no longer required.

In the 17th century the prince-abbots and their worldly magistrates, the Landeshofmeister, began to organise the abbatial sovereign territories more strictly and to subject them to an at least tentatively modern governance in the frame of the absolutist practice of the day. That resulted in conflicts by the infringement of the Protestant clergy by the abbatial authorities. In 1663, for example, the abbatial governor of Toggenburg in Lichtensteig, Wolfgang Friedrich Schorno, sentenced a vicar, Jeremias Braun, to death because he had allegedly committed blasphemy during a Reformed sermon. Only through interference by the Protestant Canton of Appenzell Ausserrhoden was Braun's punishment reduced to banishment. Four years later, through the intervention of their protector cantons, the Toggenburgers succeeded in having abbot Gallus Alt (r. 1654–1687) remove Schorno from office.

In 1695, in the framework of the Counter-Reformation, the seven Catholic cantons of the Confederacy and the prince-abbot of St Gall formed an alliance for the salvation of Catholicism against the "un-Catholic religion". To strengthen the connections between the Imperial Abbey and Catholic Central Switzerland, Schwyz proposed to Prince-Abbot Leodegar Bürgisser (r. 1696–1717) in 1699 the construction of a new road over the Ricken Pass between Uznach and Wattwil. That would be strategically and economically important for the Catholic cantons by enabling a rapid movement of Catholic troops to Toggenburg and the Princely Lands in case of war.

After the settlement of the "Cross War" with the Reformed Imperial City of St. Gallen in 1697, Bürgisser ordered the municipality of Wattwil to start constructing the road over the Ricken Pass on the Toggenburg side through socage. The refusal of the Wattwilers to collaborate in building the road, which they regarded as a threat to their religious freedom and as leading to their financial suppression, caused a serious conflict with the prince-abbot, who eventually resorted to incarcerating the highest Toggenburg magistrate, the Landweibel Josef Germann, in order to break the opposition. Because Germann was a Catholic, the Toggenburgers' complaints were heard by the protector cantons, which began acting on behalf of the Toggenburgers. In that situation, Landeshofmeister Fidel von Thurn moved Bürgisser to seek diplomatic ties within the Holy Roman Empire, and a treaty of protection was concluded with Emperor Leopold I of Habsburg in 1702.[5] Bürgisser even received the investiture as Imperial Prince in 1706. Those events threatened to raise the conflict to a European level. Moreover, that constituted a grave breach of the structure and sovereignty of the Confederacy since the Imperial Abbey of St Gall seemed to escape all of the influence of the Confederacy (despite St Gall being a member since 1451) and to enter into the Austrian sphere of influence (the Swiss had fought for centuries to uphold their independence from the Habsburgers). Especially both Appenzells but also Zürich could not accept such a turn of affairs. Also, the Princely Lands housed the fourth greatest population within the Confederacy, and they had essential economic importance in eastern Switzerland.[6]

The Toggenburgers sought and found allies, mainly in their protector cantons, Schwyz and Glarus, with which they renewed their Landrecht in 1703 and 1704. Moreover, the Protestant outposts of Zürich and Bern were becoming more and more supportive of the Toggenburg cause. In 1707, they presented the prince-abbot with a mediation proposal in which Toggenburg would be granted far-reaching autonomy, but Bürgisser did not respond. A series of events then began, which would eventually escalate to war.[5]

Escalation of crisis

[edit]

The first step towards escalation was made by the Toggenburgers, with the approval of Bern and of Zürich, by adopting a design for a constitution on 23 March 1707 at a Landsgemeinde at Wattwil, which installed an autonomous governance for Toggenburg and maintained the sovereignty of the Imperial Abbey of St Gall over it. The Toggenburgers thus acted upon the example given by Appenzell as a Landsgemeinde democracy. All abbatial magistrates and the governor were extradited and freedom of religion was promulgated, which obviously threatened the Catholic cantons' interests. The Catholic protector canton of Schwyz defected to the camp of the prince-abbot, and the conflict now assumed a clearly religious character. The Confederacy chose sides along its fault lines of faith for either the prince-abbot of St Gall or the Reformed Toggenburgers. Attempts at mediation by both Imperial and French envoys to the Confederacy failed, and the Reformed cantons urged for settling the conflict before the end of the War of the Spanish Succession to reduce the chance of a foreign intervention.

The struggle reached such a peak that the Toggenburgers armed themselves with the support of Zürich, and they occupied the abbatial fortresses at Lütisburg, Iberg and Schwarzenbach in 1710. Religious strife was now splitting the Toggenburgers themselves along religious boundaries in the moderate "Lime Tree" (Linde) and the radical "Pine" (Harte). In 1711, several Catholic municipalities once again subjected themselves to the abbot. The "Pines" then militarily occupied the municipalities, the abbatial goods and the monasteries of Magdenau and Neu St. Johann with the tacit approval of Bern and Zürich. That incident definitively forced the prince-abbot to take military counteractions and spread the crisis throughout Confederacy.

On 13 April 1712, Bern and Zürich published a manifesto against the prince-abbot of St Gall and so revealed their support for the Toggenburgers. The five Catholic inner cantons of Lucerne, Schwyz, Uri, Zug and Unterwalden published a countermanifesto, and armed themselves for war. Bern and Zürich found support with the city of Geneva and the Principality of Neuchâtel as well as its allies in the Prince-Bishopric of Basel: Biel, Moutier and La Neuveville. The five cantons found support with Valais[1] and in their Vogteien in Ticino as well as in the Freie Ämter. The remaining cantons stayed neutral, the Catholic cantons of Fribourg and Solothurn without regard to Bern and France, the Reformed city of St Gallen was surrounded by the abbatial territory and Glarus was internally divided. The Three Leagues mobilised in favour of the Protestant cause because of their alliance with Zürich from 1707, but they did not participate in any combat actions.

Course of war

[edit]As Bern and Zürich had long been preparing for war, they seized the offensive. Bern opened the first war phase on 26 April, when its first troops crossed the river Aar at Stilli to support Zürich with the occupation of Thurgau and the assault on the abbatial lands. In mid-May, about 3000 Zürichers, 2000 Bernese, 2000 Toggenburgers and 1800 Protestant Thurgauers marched into the Princely Lands. They hit upon the abbatial city of Wil, which fell on 22 May after a short siege.[7] The allies then pushed forward to St. Gallen and occupied the Abbey of Saint Gall and the Vogtei Rheintal. The abbot fled to Neuravensburg, a lordship north of Lake Constance that the abbey had acquired in 1699. The five Catholic cantons occupied Rapperswil, but initially left the abbot without any support. According to the time's laws of war, the abbey and its goods were put an under a military governance, and its chattel and riches were sent to Bern and Zürich.

Just like in the First War of Villmergen, the Canton of Aargau became the most important scene of combat. The five cantons occupied the cities of Baden, Mellingen and Bremgarten with their strategic fords and thereby threatened to drive a wedge between Zürich and Bern. The Bernese immediately launched a counteroffensive under the command of General-Major Jean de Sacconay. On 22 May, the forces had clashed in the County of Baden near Mellingen. The battle went in favour of the Bernese, who then took the city. On 26 May, they were also victorious at the Battle of Fischbach, and occupied Bremgarten. United with the Zürcher troops, the Bernese marched towards Baden, which was forced to surrender on 1 June. The fortress of the Catholic city, the Stein, which had been built after the First War of Villmergen despite protests from the Reformed cantons, was immediately destroyed to symbolise the Protestant victory. Bern and Zürich had now successfully prevented the five cantons from splitting them in Aargau. The five cantons moved towards peace negotiations on 3 June, and on 18 July 1712, Zürich, Bern, Lucerne and Uri signed a treaty in Aarau. It decided that the five cantons would lose their share in the Gemeine Herrschaften of the County of Baden and (partially) the Freie Ämter.

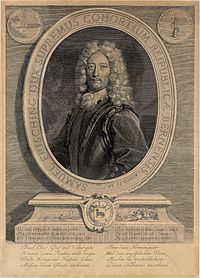

The second and much bloodier phase of the war was triggered by the Landsgemeinden of Schwyz, Zug and Unterwalden who, after being influenced by the papal nuncio, Giacomo Caracciolo, had rejected the Treaty of Aarau. In Lucerne and Uri, the people also demanded from the government to take up arms once more against the Protestant cantons. On 20 July, the first strike of the forces of the five cantons on the Bernese armed bands occurred at Sins, which then retreated to join the main guard of Bern at Muri (Battle of Sins). On 22 July, the Schwyzer and Zuger troops launched a failed attack against the Zürcher redoubts at Richterswil and Hütten. On 25 July, Villmergen once again became the site of the decisive battle. The 8000-strong Bernese companies under the command of Samuel Frisching, Niklaus von Diesbach and Jean de Sacconay fought against 12,000 men from Central Switzerland under command of Franz Konrad von Sonnenberg and Ludwig Christian Pfyffer. The long-undecided battle was finally determined by the intervention of a fresh corps from Seengen and Lenzburg as well as the superior Bernese artillery. During the battle 2,000 Catholics were killed.[8]

After their victory in the Second Battle of Villmergen, the Bernese and the Zürichers advanced into the Lucernese territory, the land of Zug, across the Brünig Pass to Unterwalden and via Rapperswil to the Linthebene. That made the resistance of the five cantons finally collapse.[9]

Peace of Aarau or "Fourth Landfrieden"

[edit]At the Peace of Aarau of 11 August 1712, the Fourth Landfrieden in the history of the Confederacy, Bern and Zürich secured their rule over the Gemeine Herrschaften. The political hegemony of the Catholic cantons in the Gemeine Herrschaften since 1531 thus came to an end.[10] That simultaneously meant the restoration of a compromised religious peace within the Old Confederacy.

The territorial conditions for peace were somewhat sharpened from those of the first peace treaty:

- Zürich and Bern, together with Glarus, maintained their ownership of the County of Baden and the lower Freie Ämter, limited by a line between Oberlunkhofen and Fahrwangen. That secured the military connection between Zürich and the Bernese land of Aargau and blocked the Catholic cantons' access to the north.

- The lordship of Rapperswil was acquired by Zürich, Bern and Glarus.

- The Schwyzer Hurden (in Freienbach) became a Gemeine Herrschaft of Zürich and Bern.

- Bern now had coruled in all Gemeine Herrschaften in which it had not had a share: Thurgau, the Vogtei Rheintal, the County of Sargans and the upper Freie Ämter.

- In the Gemeine Herrschaften and Toggenburg, subjects kept their right to exercise both the Catholic and the Protestant religions.

Zürich's further claims to the County of Uznach, Höfe (lost in the Old Zürich War) and the Vogtei Gaster were not supported by Bern and the other cantons.

Juridically, the Fourth Landfrieden made the Second Landfrieden of Kappel of 1531, confirmed at the Third Landfrieden in 1656, cease to function. Therefore, Protestantism was formally treated equally before the law in the Tagsatzung as well as in the governance of the Vogteien, and all conflicts in which both religions were concerned now had parity. In the Landvogteien Thurgau, Baden, Sargans and Rheintal, the Reformed municipalities kept the guarantee of their religious exercise under Zürcher sovereignty, and the rights of the Catholics were secured. Instead of mere tolerance, the Protestants now received equal treatment before the law to the traditionally-favoured Catholic religion. A "Landfriedliche Kommission", composed of representatives from Zürich, Bern, Lucerne and Uri, began to oversee matters of religion.[11]

The prince-abbot of Saint Gall, Leodegar Bürgisser, went into exile with his convent on 29 May to Neuravensburg Castle, the residence of a new lordship of St Gall north of Lindau. Zürich and Bern occupied the Princely Lands and governed it together. Many of the monastic movable goods that were left behind in St. Gallen, including parts of the archive and the library, were taken away by them. Because of what he considered to be outrageous damage to the rights of the Imperial Abbey, as well as the danger posed to the Catholic religion in Toggenburg, Bürgisser obtained the Peace of Rohrschach, which was finally approved on 28 March 1714 after a series of negotiations with Zürich and Bern. After the death of Bürgisser, a new treaty, the Peace of Baden, was concluded with his successor, Joseph von Rudolphi (r. 1717–1740) on 16 June 1718. The Imperial Abbey of St Gall was restored, including its rule over Toggenburg, and its autonomy and freedom of religion were confirmed.

Zürich and Bern ratified the Peace on 11 August 1718. The fact that Pope Clement XI soon denounced the peace in a letter no longer had any effect on the settlement of the conflict. Abbot von Rudolphi returned to the monastery of St Gall on 7 September 1718 after a six-year exile. On 23 March 1719, he managed to retrieve a large part of the library that was removed to Zürich at the start of the war. Further objects from the Bernese spoils of war were returned to St Gallen in 1721. However, several valuable pieces of the monastic library of St. Gallen remained in Zürich, including manuscripts, paintings, astronomy tools and the globe of St. Gallen. The conflict on the cultural goods (Kulturgüterstreit) between Zürich and St. Gallen flared up in the 1990s but was finally settled amicably in 2006.

The animosity between the Imperial Abbey and Toggenburg increased further until the abolishment of the monastic state in 1798, after two abbatial magistrates had been murdered in 1735 and after a 1739 conference in Frauenfeld between the parties had failed to yield any results.

See also

[edit]- First War of Kappel (1529)

- Second War of Kappel (1531)

- First War of Villmergen (1656)

- Sonderbund War (1847)

References

[edit]- ^ a b At the time, Valais (known as the Republic of the Seven Tithings) was still an associate of the Confederacy, not a Swiss canton, and so there were only five cantons on the Catholic side. It was only in 1815 that Valais became a full member of the new Swiss Confederacy.

- ^ (in Dutch) Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "Zwitserland. §5.2 Reformatie". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- ^ Graham Nattrass, The Swiss civil war of 1712 in contemporary sources The British Library Journal 19 (1993), pp. 11–33; Nattrass, "Further sources for the Swiss civil war of 1712 in the British Library's collections", The British Library Journal 25 (1999), pp. 164–79.

- ^ (in German) Im Hof: Ancien Régime. 1977, p. 694.

- ^ a b Second War of Villmergen in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ Im Hof: Ancien Régime. (1977) p. 695.

- ^ Walter Schaufelberger, "Blätter aus der Schweizer Militärgeschichte", Schriftenreihe der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft für Militärhistorische Studienreisen (GMS) Volume 15 (Frauenfeld 1995) p. 158. Huber. ISBN 3-7193-1111-2.

- ^ Clodfelter, Micheal (1992). Warfare and Armed Conflicts. Jefferson, North Carolina and London: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 16. ISBN 0-89950-814-6.

- ^ "Villmergerkriege", in: Historisch-Biographisches Lexikon der Schweiz. Band 7: Tinguely – Zyro. Administration des historisch-biographischen Lexikons der Schweiz (Neuchâtel 1934), p. 259f.

- ^ "Aarauer Friede." In: Historisch-Biographisches Lexikon der Schweiz. Band 1: A – Basel. (Neuchâtel 1921), p. 8. Administration des historisch-biographischen Lexikons der Schweiz.

- ^ Im Hof: Ancien Régime. (1977) p. 699.

Literature

[edit]- (in German) Gottfried Guggenbühl, Zürichs Anteil am Zweiten Villmergerkrieg, 1712 (= Schweizer Studien zur Geschichtswissenschaft, Band 4, Nr. 1, ZDB-ID 503936-8[permanent dead link]). Leemann, Zürich-Selnau 1912 (Zugleich: Zürich, Universität, Dissertation, 1911/1912).

- (in German) Ulrich Im Hof, Ancien Régime. In: Handbuch der Schweizer Geschichte. Band 2. (Zürich 1977) p. 673–784. Berichthaus. ISBN 3-8557-2021-5.

- (in German) Hans Luginbühl, Anne Barth-Gasser, Fritz Baumann, Dominique Piller 1712. Zeitgenössische Quellen zum Zweiten Villmerger- oder Toggenburgerkrieg. Merker im Effingerhof (Lenzburg 2011) ISBN 978-3-8564-8139-1 (2nd print, Lenzburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-8564-8141-4).

- (in German) Martin Merki-Vollenwyder, Unruhige Untertanen. Die Rebellion der Luzerner Bauern im zweiten Villmergerkrieg (1712) (= Luzerner historische Veröffentlichungen. Band 29). Rex-Verlag, (Luzern 1995) ISBN 3-7252-0614-7 (Zugleich: Zürich, Universität, Dissertation, 1995).

- (in German) Thomas Lau, Villmergerkrieg, Zweiter (2013). Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.