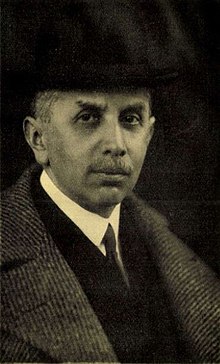

Samu Stern

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Hungarian. (August 2018) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Samu Stern | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal life | |

| Born | Samu Stern - Hungarian usage Stern Samu January 5, 1874 |

| Died | June 8, 1946 (aged 72) |

| Nationality | Hungarian |

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Judaism |

| Denomination | Neolog |

| Synagogue | probably Dohány Synagogue |

| Position | President |

| Organisation | Hungary's Neologue Community |

Samu Stern[1][2] (Hungarian: Stern Samu; 5 January 1874 – 8 June 1946) was a businessman, banker, advisor to the royal court, and head of Hungary's Neolog Jewish Community from 1929 to 1945.

After the March 1944 German occupation, Stern was a member of the German-created Jewish Council (Judenrat, Zsidó tanács) along with Orthodox Community leader Pinchas Freudiger. The Jewish Council was among recipients of the Vrba–Wetzler report, also known as the Auschwitz Protocols, the Auschwitz Report. It detailed the atrocities in Auschwitz.[3] Much like Rezső Kasztner (aka Rudolf), members of the Jewish Council failed to publicize the atrocities and warn the Jews of Hungary of their fate. Although Stern supported Jewish causes, he received criticism for dealing willingly with the German occupying authorities and their Hungarian collaborators.[4]

Early life

[edit]Samu Stern was born into a Neolog Jewish farming family in Nemesszalók, Veszprém County on 5 January 1874. His parents were Lipót Stern and Fáni Hoffmann. His father farmed on a large estate and traded in agricultural products. Samu Stern attended a yeshiva for two years, but then he enrolled in a trade school, against his parents' wishes.

During the Holocaust

[edit]Nazi Germany invaded the Kingdom of Hungary on 19 March 1944. The arriving Germans, altogether was known as the Eichmann-Kommando under the leadership of Adolf Eichmann, Hermann Krumey and Dieter Wisliceny sought to avoid panic in the ranks of the Jewish leadership. Hours after the occupation, Schutzstaffel (SS) officers arrived at Síp utca 12, where PIH was holding its annual general assembly, which abruptly adjourned, when news of the German invasion spread.[5] The Nazis demanded the convening of Neolog and Orthodox religious community leaders for the next day. On the morning of 20 March, they appeared at the headquarters of the PIH, fearing arrest or massacre. There, SS-Obersturmbannführer Hermann Krumey claimed that there will be "restrictions", but there is no need to fear deportation, if a centralized Jewish leadership cooperate. Upon their demand, the Jews presented a list of eight members of a Jewish council (Judenrat) to be set up.[6] According to Stern and Freudiger, the Jewish council was appointed by the Germans, while Ernő Munkácsi, the secretary-general of PIH, the entire list was compiled by Stern.[7] The Nazis insisted on the participation of actual community leaders from all denominations, but Stern granted a free hand to naming the specific people to become council members.[8] Samu Stern and his two colleagues from PIH, Ernő Pető and Károly Wilhelm formed an inner circle within the council. In the absence of formal meetings, they made most immediate, emergency decisions.[9]

Samu Stern wrote in his memoirs in 1946 that "I considered it a cowardly, unmanly and irresponsible behavior, a selfish escape and running away, if I let my fellow believers down now, right now, when leadership is needed the most, when the sacrificial work of experienced and politically connected men could perhaps help them". Regarding the latter, Stern trusted his personal connections, above all with Regent Miklós Horthy, whom he had known for two decades.[10] Stern and his colleagues were convinced that they could hold together the network of religious communities and aid organizations, and if they do not lead the council, then a some far less competent and influential staff worsens the Jews' chances of survival.[11]

On 21 March 1944 the Germans accepted Stern's list, establishing the Central Council of Hungarian Jews (Hungarian: Magyar Zsidók Központi Tanácsa), to which jurisdiction covered the whole country (i.e. national Jewish affairs) have been assigned. Stern was selected president of the new body. On 31 March, Adolf Eichmann informed Stern and his deputies that he would also include converted Jews under the jurisdiction of the Central Council of Hungarian Jews, recognizing it as the only representative body of the Jewish population in Hungary, regardless their religion.[12][13] The Jewish council took over the employees of the religious communities one by one. Samu Stern estimated the number of employees at 1,800.[14]

The new German-installed government led by Döme Sztójay passed a number of decrees restricting Jews in the following days. According to the decree of 7 April, all Jews outside Budapest, regardless of gender and age had to be transported to designated internment camps (ghettos). On 19 April 1944, Samu Stern and his colleagues wrote a memorandum to Sztójay, in which they requested an extraordinary investigation and applied for personal audience with the prime minister. Interestingly, the council members signed the paper on behalf of their former affiliation (e.g. Stern as president of MIOI and Kahan-Frankl as president of OIKI).[15] Due to restrictions on travel permits, the flow of information between Budapest and the countryside became difficult for Jews. After the war, Pető claimed that "it was not possible to communicate with the Jews in the countryside". Stern stated information came only from those who secretly fled to Budapest.[16][17] The Jewish councils had to function in complete isolation from each other from the very beginning, because the Jews were deprived of all means of communication (e.g. termination of telephone lines, mail censorship and travel ban) soon after the invasion of Hungary.[5] Under Stern, the Central Jewish Council repeatedly sent financial aid to the Jewish residents of rural ghettos. Regarding the ghettos and atrocities (i.e. deportations) in countryside, the council addressed a series of submissions to the Ministry of the Interior and other departments (including police and gendarmerie), as they were not received in person. These initiatives were pointless, since the council asked those bodies to investigate these atrocities, who were the initiators and executors of them.[18]

A ministerial decree of Andor Jaross on 22 April 1944 re-organized the Central Jewish Council as the nine-member Association of Hungarian Jews Provisional Executive Committee (Hungarian: Magyarországi Zsidók Szövetségének Ideiglenes Intéző Bizottsága) with the effect of 8 May 1944.[19] The new regulation also involved personnel changes: Béla Berend, the chief rabbi of Szigetvár, became a member on the recommendation of Zoltán Bosnyák, director of the anti-Semitic Jewish Question Institute. From the beginning, this created general distrust between him and Stern's circle. On the orders of latter, some confidential documents had to be destroyed, because it was known that "Berend had entered the Jewish Council as a traitor".[20] Because of Stern's illness, Samu Kahan-Frankl presided the inaugural meeting of the "second council" on 15 May 1944. They prepared the organization's statute on May 22, but it was never approved by the Ministry of the Interior.[21][22]

Overall the Jewish Council of Budapest was powerless in any attempt to influence events of the Holocaust in Hungary. Apart from sending memoranda, they didn't have many tools, as a result many Jewish intellectuals committed suicide.[23] A council's memorandum with the date 8 June to the Sztójay cabinet urged the suspension of deportations and recommended the Jews' active participation in physical work and labour service. The council was clearly playing to gain time, since the approach of the Soviet army was increasingly expected.[24] Some Zionists encouraged resistance in leaflets, but found no supporters among the Jews.[25] Samu Stern and his fellow council-members initially supported the idea, but in the end they backed off because they were afraid of collective retort.[26] An armed resistance was a stillborn idea: most of the young and healthy Jews were forced into labor service units and even significant non-Jewish armed (partisan) resistance took no place in Hungary during that period.[27] Instead, the council tried to make embassies aware of the content of the smuggled Auschwitz Protocols.[28] Sándor Török, the Converted member of the council successfully delivered the collection of eyewitness accounts to Regent Miklós Horthy via the latter's daughter-in-law Ilona Edelsheim-Gyulai on 3 July 1944.[25][29]

This process also contributed to the fact that Horthy suspended and prevented the deportation of Budapest's Jews on 7 July 1944. Historian László Bernát Veszprémy highlighted that the Central Jewish Council played a major role in the implementation of the so-called Koszorús campaign, when armor-colonel Ferenc Koszorús and the First Armour Division, under Horthy's orders, resisted the gendarmerie units and prevented the deportation of the Jews of Budapest. Koszorús blocked the roads with his army and instructed Secretary of State for the Interior László Baky to drive the gendarmes out of Budapest, who were allegedly preparing for a coup d'état against Horthy. According to Ernő Pető's recollections from 1946, Stern, Wilhelm and him held negotiations with László Ferenczy more times to implement the plan.[30] Stern and Wilhelm confirmed this in Ferenczy's trial in the same year, although the dates are often confused. Through Zoltán Bosnyák, Béla Berend liaised Ferenczy with members of the Jewish council prior to that, as Berend recalled. Captain Leó László Lulay, Ferenczy's interpreter confirmed that these meetings had taken place. According to him, the members of the Jewish council handed over such documents to Ferenczy that caused Horthy "took an unshakable stand against further deportations". Ferenczy testified the so-called "Baky coup" was a mere fabrication invented by Horthy's staff and the Jewish council together to prevent the deportations in Budapest. The plan was drafted in the apartment of Samu Stern.[31]

In the upcoming weeks, Miklós Horthy kept promising Edmund Veesenmayer, the Reich plenipotentiary in Hungary, and the collaborationist Ministry of the Interior that the deportations would continue, but he always pushed back the deadlines. According to Veszprémy, a mock plan was drawn up, with the cooperation of the Jewish council, that the Jews of Budapest are gathered in internment camps beyond the city limits. Beside Stern and his colleagues, Ottó Komoly also took part in the negotiations throughout in August 1944. This plan also served to bide time until the Red Army crossed the country's border. This dangerous plan caused serious controversy within the council. Ernő Boda, an old-new member of the council, strongly opposed the activity of Stern, Pető and Wilhelm in this case.[32] Stern personally negotiated with Horthy in early September. Both Stern and Berend recalled that Ferenczy actively participated in the process, which served to deceive the Germans. Stern later dissuaded the regent from this plan, because concentrating the Jews in one place would have made it easier for the Gestapo to deport or annihilate them, as Pető and Stern himself remembered.[33] Wilhelm argued, however, that Horthy abandoned the plan under the pressure of Franklin D. Roosevelt. By late August, Ottó Komoly and Rudolf Kastner also opposed the plan. According to Béla Berend, general distrust between the council and Horthy's staff (mainly the gendarmes Ferenczy and Lulay) ended this project.[34]

In the second half of September 1944, now under the premiership of Géza Lakatos in a more optimistic situation, the Central Jewish Council attempted to contact the Hungarian Front, an illegal anti-fascist resistance network of banned parties and organizations. Stern claimed that they even provided financial aid to the organization.[35] However the Arrow Cross Party took power on 15 October, when Nazi Germany launched the covert Operation Panzerfaust which resulted the arrest of Miklós Horthy. Following the Arrow Cross Party's coup, the Central Jewish Council was largely inactive for the next ten days. The new council consisted of president Samu Stern, his deputy Lajos Stöckler, and six members.[36] Ernő Pető and Károly Wilhelm went into hiding, therefore, their participation was omitted. Soon, Samu Stern followed them. They were informed that Ferenczy wanted to arrest and kill all three of them, because they knew compromising things (see above) about him in the eyes of the Germans.[37] Therefore, after 28 October, Stöckler acted as de facto chair of the body, but Stern remained the nominal head of the Jewish Council of Budapest.[36] During the establishment of the Budapest Ghetto in November 1944, its leaders Béla Berend and Miksa Domonkos was in contact with the ailing Stern and Wilhelm, knowing their hiding place, a damp cellar.[38]

Later life

[edit]The accusations began immediately after the World War II in connection with the evaluation of the activities of the Jewish Council of Budapest.[39] To prevent accusations, several former members of all Jewish councils wrote their memoirs, including Samu Stern (with the title Versenyfutás az idővel!, lit. "A Race with Time").[40]

The surviving members of the Jewish councils were became subjects instantly in the show trials prepared by the Communist-dominated people's courts. In May 1945, an investigation was launched against Samu Stern too. In November 1945, investigators searched the apartments of Stern and Károly Wilhelm, where they allegedly seized foreign currencies and Wilhelm was arrested. Szabad Nép, the official newspaper of the Hungarian Communist Party (MKP) connected the amounts to the collaborative behavior of the once Jewish Council of Budapest, who "only helped rich Jews" at that time. Journalist and party member Oszkár Betlen determined that there are two types of Jews: "worthy" workers and "spineless" ones. For the latter, "any kind of suffering can't be excused, we have to liquidate them and we will do it." The satirical Ludas Matyi mocked the activity of Stern and the Jewish council during the Holocaust with caricatures. Samu Stern died on 8 June 1946, at the age of 72, which thus made the unfolding of the show trial impossible. The investigation was officially closed only in August 1948.[41]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "YIVO | Stern, Samu".

- ^ "Dr. Samuel Stern, Leader of Hungarian Jewry, Dies in Budapest". 1946-06-17.

- ^ Randolph L. Braham: The Politics of Genocide, 1990, p. 711f.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2003-11-30. Retrieved 2024-12-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b Braham 1981, p. 419.

- ^ Braham 1981, p. 421.

- ^ Munkácsi 1947, p. 17.

- ^ Kádár & Vági 2008, p. 73.

- ^ Braham 1981, p. 422.

- ^ Schmidt 1990, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Kádár & Vági 2008, p. 78.

- ^ Molnár 2002, p. 99.

- ^ Munkácsi 1947, pp. 28–33.

- ^ Veszprémy 2023, pp. 127–130.

- ^ Molnár 2002, p. 103.

- ^ Schmidt 1990, pp. 69, 74, 329.

- ^ Molnár 2002, p. 107.

- ^ Braham 1981, p. 450.

- ^ Munkácsi 1947, pp. 71–73.

- ^ Schmidt 1990, pp. 75, 326.

- ^ Molnár 2002, p. 104.

- ^ Munkácsi 1947, p. 75.

- ^ Munkácsi 1947, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Karsai 1967, pp. 173–176.

- ^ a b Veszprémy 2023, pp. 152–155.

- ^ Munkácsi 1947, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Kádár & Vági 2008, p. 83.

- ^ Schmidt 1990, pp. 71, 75.

- ^ Kádár & Vági 2008, p. 89.

- ^ Schmidt 1990, pp. 83, 86–90.

- ^ Veszprémy 2023, pp. 156–165.

- ^ Schmidt 1990, pp. 130, 144–146.

- ^ Schmidt 1990, p. 94.

- ^ Veszprémy 2023, pp. 166–170.

- ^ Kádár & Vági 2008, p. 77.

- ^ a b Braham 1981, p. 469.

- ^ Schmidt 1990, p. 96.

- ^ Veszprémy 2023, pp. 182–184.

- ^ Munkácsi 1947, p. 40.

- ^ Schmidt 1990, p. 100.

- ^ Veszprémy 2023, pp. 211–212.

Sources

[edit]- Braham, Randolph L. (1981). The Politics of Genocide: The Holocaust in Hungary. Vol. 1–2. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-04496-8.

- Kádár, Gábor; Vági, Zoltán (2008). "Compulsion of Bad Choices. Questions, Dilemmas, Decisions: The Activity of the Hungarian Central Jewish Council in 1944". In Kovács, András (ed.). Jewish Studies at the Central European University, 2005–2007. CEU Press. pp. 71–89. ISBN 978-9637326721.

- Karsai, Elek (1967). Vádirat a nácizmus ellen. Dokumentumok a magyarországi zsidóüldözés történetéhez [An Indictment against Nazism. Documents for the History of the Persecution of Jews in Hungary] (in Hungarian). Vol. 3. Budapest: National Representation of Hungarian Israelites (MIOK).

- Molnár, Judit (2002). "The Foundation and Activities of the Hungarian Jewish Council, March 20 – July 7, 1944". Yad Vashem Studies. 30: 93–123. ISSN 0084-3296.

- Munkácsi, Ernő (1947). Hogyan történt? Adatok és okmányok a magyar zsidóság tragédiájához [How It Happened: Documenting the Tragedy of Hungarian Jewry] (in Hungarian). Budapest: Renaissance.

- Schmidt, Mária (1990). Kollaboráció vagy kooperáció? A Budapesti Zsidó Tanács [Collaboration or Cooperation? The Jewish Council of Budapest] (in Hungarian). Budapest: Minerva. ISBN 963-223-438-3.

- Veszprémy, László Bernát (2023). Tanácstalanság. A zsidó vezetés Magyarországon és a holokauszt, 1944–1945 [Bereft of Council. Jewish leadership in Hungary during the Holocaust in 1944–1945] (in Hungarian). Budapest: Jaffa Kiadó. ISBN 978-963-475-731-3.

External links

[edit]- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2003-11-30. Retrieved 2024-12-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Historical Background: The Jews of Hungary During the Holocaust". www.yadvashem.org. Retrieved 2024-12-16.

Publications

[edit]- Nathaniel Katzburg, Shemu’el Shtern: Ro’sh kehilat Pesht, in Pedut: Hatsalah bi-yeme sho’ah (Ramat Gan, Isr., 1984)

- Mária Schmidt, Kollaboráció vagy kooperáció? (Budapest, 1990), pp. 49–111

- Samu (Samuel) Stern, A Race with Time: A Statement, Hungarian Jewish Studies 3 (1973): 1–48