SMS Don Juan d'Austria (1862)

1864 illustration of Don Juan d'Austria

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Don Juan d'Austria |

| Namesake | John of Austria |

| Builder | Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino |

| Laid down | October 1861 |

| Launched | 26 July 1862 |

| Commissioned | 1863 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Kaiser Max class |

| Displacement | 3,588 long tons (3,646 t) |

| Length | 70.78 m (232 ft 3 in) pp |

| Beam | 10 m (32 ft 10 in) |

| Draft | 6.32 m (20 ft 9 in) |

| Installed power | 1,926 indicated horsepower (1,436 kW) |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 11.4 knots (21.1 km/h; 13.1 mph) |

| Range | 1,200 nautical miles (2,200 km; 1,400 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Crew | 386 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor | Belt: 110 mm (4.3 in) |

SMS Don Juan d'Austria[a] was the third member of the Kaiser Max class built for the Austrian Navy in the 1860s. Her keel was laid in October 1861 at the Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino shipyard; she was launched in July 1862, and was completed in 1863. She carried her main battery—composed of sixteen 48-pounder guns and fifteen 24-pounders—in a traditional broadside arrangement, protected by an armored belt that was 110 mm (4.3 in) thick.

Don Juan d'Austria saw action at the Battle of Lissa in July 1866. There she was heavily engaged in the center of the melee; she traded broadsides with the Italian ironclad Re di Portogallo and was hit three times by the turret ship Affondatore, though she received little damage. After the war, Don Juan d'Austria was modernized slightly in 1867 to correct her poor seakeeping and improve her armament, but she was nevertheless rapidly outpaced by naval developments in the 1860s and 1870s. Obsolescent by 1873, Don Juan d'Austria was officially "rebuilt", though in actuality she was broken up for scrap, with only her armor plate, parts of her machinery, and other miscellaneous parts being reused in the new Don Juan d'Austria.

Design

[edit]Having already secured funding for the two Drache-class ironclads, the head of the Austrian Navy, Archduke Ferdinand Max, argued in 1862 for an expanded fleet of ironclad warships as part of the Austro-Italian ironclad arms race. He requested a total force of nine ironclads, which would counter the known construction program of the Italian Regia Marina—then at four ironclads already ordered, with more funding authorized for future vessels. For 1862, he proposed building three ironclads, along with converting a pair of sail frigates to steam frigates. The Austrian Reichsrat (Imperial Council) refused to grant funding for the program, but Kaiser Franz Joseph intervened and authorized the navy to place orders for the new ships, which became the Kaiser Max class.[3]

Don Juan d'Austria was 70.78 meters (232 ft 3 in) long between perpendiculars; she had a beam of 10 m (32 ft 10 in) and an average draft of 6.32 m (20 ft 9 in). She displaced 3,588 long tons (3,646 t). She had a crew of 386. Her propulsion system consisted of one single-expansion steam engine that drove a single screw propeller. The number and type of her coal-fired boilers have not survived. Her engine produced a top speed of 11 knots (20 km/h; 13 mph) from 1,900 indicated horsepower (1,400 kW). She could steam for about 1,200 nautical miles (2,200 km; 1,400 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[1]

Don Juan d'Austria was a broadside ironclad, and she was armed with a main battery of sixteen 48-pounder muzzle-loading guns and fifteen 24-pounder 15 cm (5.9 in) rifled muzzle-loading guns. She also carried a single 12-pounder gun and a six-pounder. The sides of ship's hull were sheathed with wrought iron armor that was 110 mm (4 in) thick and extended from bow to stern.[1]

Service history

[edit]Don Juan d'Austria was built by the Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino (STT) shipyard. She was laid down in October 1861, and her completed hull was launched on 26 July 1862. Fitting-out work was completed the following year and she was commissioned into the Austrian fleet the following year. She proved to be very wet forward, owing to her open bow, and as a result, tended to handle poorly.[1] In February 1864, the Austrian Empire joined Prussia in the Second Schleswig War against Denmark. Don Juan d'Austria was sent with the wooden ship of the line Kaiser, the screw corvette Erzherzog Friedrich, and the paddle steamer Elisabeth under Vice Admiral Bernhard von Wüllerstorf-Urbair to reinforce a smaller force consisting of the screw frigates Schwarzenberg and Radetzky under then-Captain Wilhelm von Tegetthoff. After the two groups combined in Den Helder, the Netherlands, they proceeded to Cuxhaven on 27 June, arriving three days later. The now outnumbered Danish fleet remained in port for the rest of the war and did not seek battle with the Austro-Prussian squadron. Instead, the Austrian and Prussian naval forces supported operations to capture the islands off the western Danish coast.[4]

In June 1866, Italy declared war on Austria, as part of the Third Italian War of Independence, which was fought concurrently with the Austro-Prussian War.[5] Tegetthoff, by now promoted to rear admiral and given command of the entire fleet, brought the Austrian fleet to Ancona on 27 June, in an attempt to draw out the Italians, but the Italian commander, Admiral Carlo Pellion di Persano, did not sortie to engage Tegetthoff.[6] The Italian failure to give battle is frequently cited as an example of Persano's cowardice, but in fact, the Italian fleet was taking on coal and other supplies after the voyage from Taranto, and was not able to go to sea.[7] Tegetthoff made another sortie on 6 July, but again could not bring the Italian fleet to battle.[8]

Battle of Lissa

[edit]

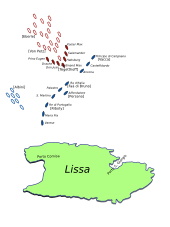

On 16 July, Persano took the Italian fleet, with twelve ironclads, out of Ancona, bound for the island of Lissa, where they arrived on the 18th. With them, they brought troop transports carrying 3,000 soldiers.[5] Persano then spent the next two days bombarding the Austrian defenses of the island and unsuccessfully attempting to force a landing. Tegetthoff received a series of telegrams between 17 and 19 July notifying him of the Italian attack, which he initially believed to be a feint to draw the Austrian fleet away from its main bases at Pola and Venice. By the morning of the 19th, however, he was convinced that Lissa was in fact the Italian objective, and so he requested permission to attack. As Tegetthoff's fleet arrived off Lissa on the morning of 20 July, Persano's fleet was arrayed for another landing attempt. The latter's ships were divided into three groups, with only the first two able to concentrate in time to meet the Austrians. Tegetthoff had arranged his ironclad ships into a wedge-shaped formation, with Don Juan d'Austria on his right flank; the wooden warships of the second and third divisions followed behind in the same formation.[9]

While he was forming up his ships, Persano transferred from his flagship, Re d'Italia, to the turret ship Affondatore. This created a gap in the Italian line, and Tegetthoff seized the opportunity to divide the Italian fleet and create a melee. He made a pass through the gap, but failed to ram any of the Italian ships, forcing him to turn around and make another attempt. Don Juan d'Austria initially attempted to follow Tegetthoff's flagship, Erzherzog Ferdinand Max, but quickly lost contact with her in the ensuing melee. Don Juan d'Austria became surrounded by Italian vessels, prompting her sister Kaiser Max to come to her aid. Don Juan d'Austria thereafter engaged Re di Portogallo for around half an hour before shifting targets back to Affondatore. The latter scored three hits on Don Juan d'Austria's unarmored bow, but they caused little damage. The first passed directly through the ship without exploding, the second struck the belt armor and failed to penetrate, and the third hit her quarterdeck.[10]

By this time, Re d'Italia had been rammed and sunk and the coastal defense ship Palestro was burning badly, soon to be destroyed by a magazine explosion. Persano broke off the engagement, and though his ships still outnumbered the Austrians, he refused to counter-attack with his badly demoralized forces. In addition, the fleet was low on coal and ammunition. The Italian fleet began to withdraw, followed by the Austrians; Tegetthoff, having gotten the better of the action, kept his distance so as not to risk his success. As night began to fall, the opposing fleets disengaged completely, heading for Ancona and Pola, respectively.[11]

Later career

[edit]After returning to Pola, Tegetthoff kept his fleet in the northern Adriatic, where it patrolled against a possible Italian attack. The Italian ships never came, and on 12 August, the two countries signed the Armistice of Cormons; this ended the fighting and led to the Treaty of Vienna. Though Austria had defeated Italy at Lissa and on land at the Battle of Custoza, the Austrian army was decisively defeated by Prussia at the Battle of Königgrätz. As a result, Austria, which became Austria-Hungary in the Ausgleich of 1867, was forced to cede the city of Venice to Italy. In the immediate aftermath of the war, the bulk of the Austrian fleet was decommissioned and disarmed.[12]

The fleet embarked on a modest modernization program after the war, primarily focused on re-arming the ironclads with new rifled guns.[13] Don Juan d'Austria was rebuilt in 1867, particularly to correct her poor sea-keeping. Her open bow was plated over and she was rearmed with twelve 7-inch (178 mm) muzzleloaders manufactured by Armstrong and two 3-inch (76 mm) 4-pounder guns. By 1873, the ship was obsolescent and had a thoroughly-rotted hull, so the Austro-Hungarian Navy decided to replace the ship. Parliamentary objection to granting funds for new ships forced the navy to resort to subterfuge to replace the ship. Reconstruction projects were routinely approved by the parliament, so the navy officially "rebuilt" Don Juan d'Austria and her sister ships. In reality, only some parts of the engines, armor plate, and other miscellaneous parts were salvaged from the ships. Don Juan d'Austria was dismantled at the STT shipyard beginning in December 1873. The new ironclads were given the same names of the old vessels in an attempt to conceal the deception.[14]

Footnotes

[edit]Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d Sieche & Bilzer, p. 268.

- ^ Sondhaus 1994, p. 72.

- ^ Sondhaus 1989, pp. 211–213.

- ^ Greene & Massignani, pp. 210–211.

- ^ a b Sondhaus 1994, p. 1.

- ^ Wilson, pp. 216–218, 228.

- ^ Sondhaus 1989, p. 253.

- ^ Wilson, p. 229.

- ^ Wilson, pp. 221–, 229–231.

- ^ Wilson, pp. 232–235, 243.

- ^ Wilson, pp. 238–241, 250.

- ^ Sondhaus 1994, pp. 1–3, 8.

- ^ Sondhaus 1994, p. 10.

- ^ Sieche & Bilzer, pp. 268, 270.

References

[edit]- Greene, Jack & Massignani, Alessandro (1998). Ironclads at War: The Origin and Development of the Armored Warship, 1854–1891. Pennsylvania: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-938289-58-6.

- Sieche, Erwin & Bilzer, Ferdinand (1979). "Austria-Hungary". In Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M. (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 266–283. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (1989). The Habsburg Empire and the Sea: Austrian Naval Police, 1797–1866. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-0-911198-97-3.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-034-9.

- Wilson, Herbert Wrigley (1896). Ironclads in Action: A Sketch of Naval Warfare from 1855 to 1895. London: S. Low, Marston and Company. OCLC 1111061.