SHANK3

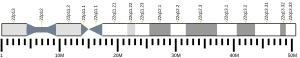

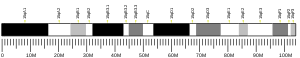

SH3 and multiple ankyrin repeat domains 3 (Shank3), also known as proline-rich synapse-associated protein 2 (ProSAP2), is a protein that in humans is encoded by the SHANK3 gene on chromosome 22.[5] Additional isoforms have been described for this gene but they have not yet been experimentally verified.

Function

[edit]This gene is a member of the Shank gene family. The gene encodes a protein that contains 5 interaction domains or motifs including the ankyrin repeats domain (ANK), a src 3 domain (SH3), a proline-rich domain, a PDZ domain and a sterile α motif domain (SAM).[6] Shank proteins are multidomain scaffold proteins of the postsynaptic density that connect neurotransmitter receptors, ion channels, and other membrane proteins to the actin cytoskeleton and G-protein-coupled signaling pathways. Shank proteins also play a role in synapse formation and dendritic spine maturation.[7]

Clinical significance

[edit]Mutations in this gene are associated with autism spectrum disorder.[8] This gene is often missing in patients with 22q13.3 deletion syndrome (Phelan–McDermid syndrome),[9] although not in all cases.[10]

Interactions

[edit]SHANK3 has been shown to interact with ARHGEF7.[11]

Mouse models

[edit]Mouse models of SHANK3 include N-terminal knock-outs[12][13] and a PDZ domain knock-out[14] all of which also show social interaction deficits and variable other phenotypes. Most of these mice are homozygous knock-outs whereas all the human SHANK3 mutations have been heterozygous.

In an inducible knockout, restoration of SHANK3 expression in adult mice promoted dendritic spine growth and recovered normal grooming behaviour and voluntary social interaction.[15] However, the reduced locomotion, anxiety and rotarod deficits remained. Germline restoration of the gene's expression rescued all measured phenotypes. Experiments on different developmental windows suggested that early intervention was more effective in restoring behavioural traits.

Rat models

[edit]A rat model of SHANK3 was developed using zinc finger nucleases targeting exon 6 of the ankyrin (ANK) repeat domain. The deletion (-68bp) resulted in reduction of the full length SHANK3a protein. It is unclear if the expression of other isoforms (b and c) of SHANK3 is affected in this rodent model. The shank3 mutant rats have deficits in long-term social recognition memory but not short-term social recognition memory as well as deficits in attention.[16] These mutants also have impaired synaptic plasticity. In humans, 5 patients have been described harboring varying mutations in exon 6 of the SHANK3 protein.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000251322 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000022623 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: SHANK3 SH3 and multiple ankyrin repeat domains 3".

- ^ Sheng M, Kim E (June 2000). "The Shank family of scaffold proteins". Journal of Cell Science. 113 ( Pt 11) (11): 1851–6. doi:10.1242/jcs.113.11.1851. PMID 10806096.

- ^ Boeckers TM, Bockmann J, Kreutz MR, Gundelfinger ED (June 2002). "ProSAP/Shank proteins - a family of higher order organizing molecules of the postsynaptic density with an emerging role in human neurological disease". Journal of Neurochemistry. 81 (5): 903–10. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00931.x. PMID 12065602. S2CID 19894590.

- ^ Brown, EA; et al. (2018). "Clustering the autisms using glutamate synapse protein interaction networks from cortical and hippocampal tissue of seven mouse models". Molecular Autism. 9 (48). BioMed Central: 1–16. doi:10.1186/s13229-018-0229-1. PMC 6139139. PMID 30237867.

- ^ Sarasua SM, Dwivedi A, Boccuto L, Rollins JD, Chen CF, Rogers RC, Phelan K, DuPont BR, Collins JS (November 2011). "Association between deletion size and important phenotypes expands the genomic region of interest in Phelan-McDermid syndrome (22q13 deletion syndrome)". Journal of Medical Genetics. 48 (11): 761–6. doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100225. PMID 21984749. S2CID 28620399.

- ^ Simenson K, Õiglane-Shlik E, Teek R, Kuuse K, Õunap K (March 2014). "A patient with the classic features of Phelan-McDermid syndrome and a high immunoglobulin E level caused by a cryptic interstitial 0.72-Mb deletion in the 22q13.2 region". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A. 164A (3): 806–9. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.36358. PMID 24375995. S2CID 7917552.

- ^ Park E, Na M, Choi J, Kim S, Lee JR, Yoon J, Park D, Sheng M, Kim E (May 2003). "The Shank family of postsynaptic density proteins interacts with and promotes synaptic accumulation of the beta PIX guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Rac1 and Cdc42". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (21): 19220–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M301052200. PMID 12626503.

- ^ Wang X, McCoy PA, Rodriguiz RM, Pan Y, Je HS, Roberts AC, Kim CJ, Berrios J, Colvin JS, Bousquet-Moore D, Lorenzo I, Wu G, Weinberg RJ, Ehlers MD, Philpot BD, Beaudet AL, Wetsel WC, Jiang YH (August 2011). "Synaptic dysfunction and abnormal behaviors in mice lacking major isoforms of Shank3". Human Molecular Genetics. 20 (15): 3093–108. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddr212. PMC 3131048. PMID 21558424.

- ^ Bozdagi O, Sakurai T, Papapetrou D, Wang X, Dickstein DL, Takahashi N, Kajiwara Y, Yang M, Katz AM, Scattoni ML, Harris MJ, Saxena R, Silverman JL, Crawley JN, Zhou Q, Hof PR, Buxbaum JD (December 2010). "Haploinsufficiency of the autism-associated Shank3 gene leads to deficits in synaptic function, social interaction, and social communication". Molecular Autism. 1 (1): 15. doi:10.1186/2040-2392-1-15. PMC 3019144. PMID 21167025.

- ^ Peça J, Feliciano C, Ting JT, Wang W, Wells MF, Venkatraman TN, Lascola CD, Fu Z, Feng G (April 2011). "Shank3 mutant mice display autistic-like behaviours and striatal dysfunction" (PDF). Nature. 472 (7344): 437–42. Bibcode:2011Natur.472..437P. doi:10.1038/nature09965. PMC 3090611. PMID 21423165.

- ^ Mei Y, Monteiro P, Zhou Y, Kim JA, Gao X, Fu Z, Feng G (February 2016). "Adult restoration of Shank3 expression rescues selective autistic-like phenotypes". Nature. 530 (7591): 481–4. Bibcode:2016Natur.530..481M. doi:10.1038/nature16971. PMC 4898763. PMID 26886798.

- ^ Harony-Nicolas, H.; Kay, M.; Du Hoffmann, J.; Klein, M. E.; Bozdagi-Gunal, O.; Riad, M.; Daskalakis, N. P.; Sonar, S.; Castillo, P. E.; Hof, P. R.; Shapiro, M. L.; Baxter, M. G.; Wagner, S.; Buxbaum, J. D. (2017). "Oxytocin improves behavioral and electrophysiological deficits in a novel Shank3-deficient rat". eLife. 6: e18904. doi:10.7554/eLife.18904. PMC 5283828. PMID 28139198.

Further reading

[edit]- Shcheglovitov A, Shcheglovitova O, Yazawa M, Portmann T, Shu R, Sebastiano V, Krawisz A, Froehlich W, Bernstein JA, Hallmayer JF, Dolmetsch RE (November 2013). "SHANK3 and IGF1 restore synaptic deficits in neurons from 22q13 deletion syndrome patients". Nature. 503 (7475): 267–71. Bibcode:2013Natur.503..267S. doi:10.1038/nature12618. PMC 5559273. PMID 24132240.

- Tu JC, Xiao B, Naisbitt S, Yuan JP, Petralia RS, Brakeman P, Doan A, Aakalu VK, Lanahan AA, Sheng M, Worley PF (July 1999). "Coupling of mGluR/Homer and PSD-95 complexes by the Shank family of postsynaptic density proteins". Neuron. 23 (3): 583–92. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80810-7. PMID 10433269.

- Sheng M, Kim E (June 2000). "The Shank family of scaffold proteins". Journal of Cell Science. 113 ( Pt 11) (11): 1851–6. doi:10.1242/jcs.113.11.1851. PMID 10806096.

- Boeckers TM, Kreutz MR, Winter C, Zuschratter W, Smalla KH, Sanmarti-Vila L, Wex H, Langnaese K, Bockmann J, Garner CC, Gundelfinger ED (August 1999). "Proline-rich synapse-associated protein-1/cortactin binding protein 1 (ProSAP1/CortBP1) is a PDZ-domain protein highly enriched in the postsynaptic density". The Journal of Neuroscience. 19 (15): 6506–18. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-15-06506.1999. PMC 6782800. PMID 10414979.

- Hirosawa M, Nagase T, Murahashi Y, Kikuno R, Ohara O (February 2001). "Identification of novel transcribed sequences on human chromosome 22 by expressed sequence tag mapping". DNA Research. 8 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1093/dnares/8.1.1. PMID 11258795.

- Bonaglia MC, Giorda R, Borgatti R, Felisari G, Gagliardi C, Selicorni A, Zuffardi O (August 2001). "Disruption of the ProSAP2 gene in a t(12;22)(q24.1;q13.3) is associated with the 22q13.3 deletion syndrome". American Journal of Human Genetics. 69 (2): 261–8. doi:10.1086/321293. PMC 1235301. PMID 11431708.

- Soltau M, Richter D, Kreienkamp HJ (December 2002). "The insulin receptor substrate IRSp53 links postsynaptic shank1 to the small G-protein cdc42". Molecular and Cellular Neurosciences. 21 (4): 575–83. doi:10.1006/mcne.2002.1201. PMID 12504591. S2CID 572407.

- Bonaglia MC, Giorda R, Mani E, Aceti G, Anderlid BM, Baroncini A, Pramparo T, Zuffardi O (October 2006). "Identification of a recurrent breakpoint within the SHANK3 gene in the 22q13.3 deletion syndrome". Journal of Medical Genetics. 43 (10): 822–8. doi:10.1136/jmg.2005.038604. PMC 2563164. PMID 16284256.

- Durand CM, Betancur C, Boeckers TM, Bockmann J, Chaste P, Fauchereau F, Nygren G, Rastam M, Gillberg IC, Anckarsäter H, Sponheim E, Goubran-Botros H, Delorme R, Chabane N, Mouren-Simeoni MC, de Mas P, Bieth E, Rogé B, Héron D, Burglen L, Gillberg C, Leboyer M, Bourgeron T (January 2007). "Mutations in the gene encoding the synaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3 are associated with autism spectrum disorders". Nature Genetics. 39 (1): 25–7. doi:10.1038/ng1933. PMC 2082049. PMID 17173049.

- Moessner R, Marshall CR, Sutcliffe JS, Skaug J, Pinto D, Vincent J, Zwaigenbaum L, Fernandez B, Roberts W, Szatmari P, Scherer SW (December 2007). "Contribution of SHANK3 mutations to autism spectrum disorder". American Journal of Human Genetics. 81 (6): 1289–97. doi:10.1086/522590. PMC 2276348. PMID 17999366.

- Mei Y, Monteiro P, Zhou Y, Kim JA, Gao X, Fu Z, Feng G (February 2016). "Adult restoration of Shank3 expression rescues selective autistic-like phenotypes". Nature. 530 (7591): 481–4. Bibcode:2016Natur.530..481M. doi:10.1038/nature16971. PMC 4898763. PMID 26886798.