São Paulo Revolt of 1924

| São Paulo Revolt of 1924 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Tenentism | |||||||

At the top: fires in São Paulo. Middle left: machine gun position in Vila Mariana. Middle right: Cotonifício Crespi damaged by the bombings. Bottom left: effects of an air attack. Bottom right: soldiers on the roof of the 1st Battalion of the Public Force. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Revolutionary Division[2] (See order of battle) |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

On 5 July:

Mid-month: |

On 5 July:

Mid-month: | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

"ARMADURA Z29 HELMET ARMOR Z29" by OSCAR CREATIVO | |||||||

The São Paulo Revolt of 1924 (Portuguese: Revolta Paulista), also called the Revolution of 1924 (Revolução de 1924), Movement of 1924 (Movimento de 1924) or Second 5th of July (Segundo 5 de Julho) was a Brazilian conflict with characteristics of a civil war, initiated by tenentist rebels to overthrow the government of president Artur Bernardes. From the city of São Paulo on 5 July, the revolt expanded to the interior of the state and inspired other uprisings across Brazil. The urban combat ended in a loyalist victory on 28 July. The rebels' withdrawal, until September, prolonged the rebellion into the Paraná Campaign.

The conspiratorial nucleus behind the revolt consisted of army officers, veterans of the Copacabana Fort revolt, in 1922, who were joined by military personnel from the Public Force of São Paulo, sergeants and civilians, all enemies of the political system of Brazil's Old Republic. They chose the retired general Isidoro Dias Lopes as their commander and planned a nationwide revolt, starting with the occupation of São Paulo in a few hours, cutting off one of the arms of the oligarchies that dominated the country in "coffee with milk" politics. The plan fell apart: there were fewer supporters than expected and the loyalists resisted in the city's center until 8 July, when governor Carlos de Campos withdrew to the Guaiaúna rail station, on the outskirts of the city. The federal government concentrated much of the country's firepower in the city, with a numerical advantage of five to one, and began to reconquer it by the working-class neighborhoods to the east and south of the city's center, under the command of general Eduardo Sócrates.

São Paulo, the largest industrial park in the country, had its factories paralyzed by the fight, the most intense ever fought within a Brazilian city. There were food shortages and, in the power vacuum, the looting of stores began. The federal government launched an indiscriminate artillery bombardment against the city, which caused heavy damage to houses, industries and the inhabitants. Civilians were the majority of those killed and a third of the city's inhabitants became refugees. São Paulo's economic elite, led by José Carlos de Macedo Soares, president of the Commercial Association, did their best to preserve their properties and order in the city. Fearing a social revolution, the elites influenced the leaders of the revolt to distance themselves from militant workers, such as the anarchists, who had offered their support to the rebels; Macedo Soares and others also unsuccessfully tried to broker a ceasefire.

With no prospect of success in battle, the rebels still had an escape route into their occupied territory from Campinas to Bauru, but it was about to be cut off by loyalist victories in the Sorocaba axis. The revolutionary army escaped the imminent siege and moved to the banks of the Paraná River. After an unsuccessful invasion of southern Mato Grosso (the Battle of Três Lagoas), they entrenched themselves in western Paraná, where they joined rebels from Rio Grande do Sul to form the Miguel Costa-Prestes Column. The federal government reestablished the state of emergency and intensified political repression, foreshadowing the apparatus later used by the Estado Novo and the military dictatorship; in São Paulo, the Department of Political and Social Order (Deops) was created. Despite the scale of the fighting and the destruction it left, the uprising earned the nickname of "Forgotten Revolution" and does not have public commemorations equivalent to those held for the Constitutionalist Revolution of 1932.

Background

[edit]The tenentist cause

[edit]Tenentes or lieutenants and senior officers of the Brazilian Army, veterans of the 1922 Copacabana Fort revolt, were the initial nucleus of subsequent revolts, including the one in São Paulo in 1924.[8][9][10] Participation by the same individuals connects these moments,[11][12] despite new supporters and agendas in the 1924 revolt.[13] The rebellion also encompassed lower ranks of the army,[14] military personnel from the Public Force of São Paulo, and civilians.[15] Historiography addresses the tenentes as representatives of certain sectors of society (dissident oligarchies, middle classes) and also as a result of internal dynamics in the army.[16] More concerned with military honor in 1922, two years later the tenentes had already developed a political vision beyond institutional issues.[17]

These rebels or revolutionaries are more easily defined by what they were against than what they were for.[8] The 1922 revolt wanted to prevent Artur Bernardes from taking office as President of Brazil; when this failed, its 1924 successor wanted him out of office.[12] The issue was not so much the president himself, but what he represented:[18][19] the hegemony of the agrarian oligarchies of São Paulo and Minas Gerais in Brazil's politics ("coffee with milk" politics), the power of local coronelism, electoral fraud, corruption, cronyism and favoritism in public affairs, all characteristic of politics in the Old Republic.[8][20]

They were outraged by what they saw as the president's vengeful persecution of former members of the Republican Reaction, the coalition that faced him in the 1922 election.[8][21] The president submitted Rio de Janeiro to federal intervention and Bahia to a state of emergency. In Rio Grande do Sul, Bernardes prevented the re-election of Borges de Medeiros as part of the Pact of Pedras Altas, which concluded the 1923 revolution. His government had authoritarian tendencies, beginning under a state of emergency and renewing it until December 1923.[22][23][24] The 1922 rebels were subjected to a rigorous and arbitrary trial.[25]

Unlike two years earlier, the rebels of 1924 made sure to expose some proposals for the new regime in manifestos and flyers. Their ambition was the "Republic that was not", a return to an ideal that would have existed in the Proclamation of the Brazilian Republic.[26][27][28] To do so, they would break the dominance of the oligarchies over the electorate. The third manifesto published during the revolt[e] advocated a reform of the Judiciary branch, giving it independence from the Executive; public education; and secret ballots with census suffrage. Illiteracy would be eradicated, but until that was possible, voting would be limited to the most enlightened.[29]

This idea was taken further in an unpublished draft,[f] proposing a "dictatorship" until 60% of the population was literate, and then a Constituent Assembly would be convened. This document does not necessarily represent the rebels' general opinion, but it demonstrates the influence of some authoritarian thinkers of the period, such as Oliveira Viana, for whom a strong State would be necessary to prepare the population for liberalism. Other conspirators thought of corporatism.[30][29] There were a variety of reforms in mind, but they did not form a cohesive project.[31] Not all participants were ideologically motivated; some cared more about their personal commitments, economic demands[32][33][34] or dissatisfaction with their military career.[8]

Veterans decide to fight again

[edit]It is not known for certain when conspiracies for a second tenentist revolt began, but in August 1922 there were already conspiracies in Rio de Janeiro, and in the same period, in Itu, in São Paulo.[35] The atmosphere was tense and rumors circulated of further uprisings.[36] Some rebel officers of 1922 considered the matter closed, and others, although unsatisfied, were waiting for the results of the judicial trial. Meanwhile, in 1923 the revolution in Rio Grande do Sul and the reopening of the Military Club rekindled political-military discussions.[36] Many rebels awaited their sentence far from Rio de Janeiro, in conditions to join the conspiracy.[37]

In December 1923, the courts indicted the 1922 rebels on Article 107 of the Penal Code ("to change by violent means the political Constitution of the Republic or the established form of government"). Until then, there was an expectation of amnesty;[38] this procedure was traditional in previous military revolts. Precisely for this reason, the government wanted to discourage further uprisings. This refusal to grant amnesty was seen as yet another vindictive move.[39][40]

Of the 50 indicted officers, 22 were already in prison and 17, disappointed, turned themselves in. The other 11 remained underground as deserters, notably captains Joaquim Távora, Juarez Távora and Otávio Muniz Guimarães and lieutenants Vitor César da Cunha Cruz, Stênio Caio de Albuquerque Lima, Ricardo Henrique Holl and Eduardo Gomes.[41] These and other imprisoned, exiled, or clandestine officers formed a core of professional revolutionaries, for whom armed struggle seemed the only remaining option.[37] A new rebellion would need to be more sophisticated than the previous one, without improvisation and simple barracks revolts.[42] The final objective remained the seizure of power in Rio de Janeiro.[43]

In the last months of 1923, some plotters were already sounding the possibility of an uprising in the south.[41] In December, a plan to arrest War Minister Setembrino de Carvalho on his way through Ponta Grossa, Paraná, was discovered by the authorities.[44] This plan would possibly be simultaneous to a coup d'état in Rio de Janeiro, led by colonel Valdomiro Lima.[45] The government was already expecting a revolt, though not particularly in São Paulo.[46] Over the course of several months, the president was already reading confidential reports about the conspiracy.[47] In order to dismantle the conspiracy, officers were arrested or transferred to other garrisons,[48] which was to some extent counterproductive, seeding discontent to distant regions.[10][49] To demonstrate its strength, the government often placed troops at the ready, preventing officers from leaving their posts.[36]

Preparation of the uprising

[edit]São Paulo chosen as starting point

[edit]

The rebellion intended by the conspirators would have a nationwide dimension, culminating in Rio de Janeiro. The starting point, São Paulo, was the circumstantial result of military planning. Therefore, the 1924 movement was not a paulista revolt.[8][50] The initiative belonged to outsiders,[51] and they cared little about São Paulo's political disputes.[52]

In Rio, the largest military center in the country,[53] surveillance and denunciation were constant, preventing it from being the starting point.[54] The capital's political police, part of the 4th Auxiliary Bureau, was well organized, and the Chief of Police was marshal Carneiro da Fontoura, chosen by Artur Bernardes in place of the traditional law graduates.[48] In contrast, the police apparatus was weaker in São Paulo, where the state government excessively trusted its Public Force, at the time stronger than the federal army garrison in the state. The possibility of taking the Public Force into rebellion was a decisive factor in the choice for São Paulo.[55] The number of supporters in the army and in the Public Force and the correlation of military strength seemed favorable.[56]

The city's rapid growth made it difficult to identify conspirators and fugitives.[57][58] Its approximately 700,000 inhabitants in 1924 were ten times the 65,000 present in 1890.[59][60] It was the capital of the richest state in the country and center of coffee-related commercial and banking activities.[61] Initially linked to coffee production, rapid industrialization attracted many immigrants, to the point that foreigners and their descendants represented more than half of the local population.[62] Urbanism and architecture imitated European metropolises, while poor neighborhoods sprawled unplanned on the periphery.[63]

São Paulo had the best railroad connections in the country, through which Rio de Janeiro, then the federal capital, could be reached in a few hours.[8] 22% of the country's railway network was concentrated in São Paulo at the beginning of the decade, and its capital was the junction to which the Paulista, Mogiana, Sorocabana, Santos-Jundiaí, Noroeste do Brasil and Central do Brasil railways converged.[64] Its fall would have immense national repercussions,[8] cutting off the strong arm of the federal government and coffee with milk politics, and providing the rebellion with "enormous military, economic and political resources".[58][57]

In state politics, dominated by the Republican Party of São Paulo (PRP), the moment was delicate. Governor Washington Luís had forced Carlos de Campos as his successor, to the detriment of senator Álvaro de Carvalho, generating discontent. The artificial rise in the price of coffee increased the cost of living, leading to workers' strikes for wage adjustments.[54][65] Since the 1917 general strike, the so-called "social question" was a major concern.[61]

Clandestine networks

[edit]

The clandestine conspirators worked civilian jobs under false identities.[g] To enlist new allies, including officers on active duty, they resorted to their relatives and contacts built in the Military School of Realengo and in the barracks, prisons and neighborhoods.[15] It was normal for the rebels to be colleagues at the Military School, and many others met each other when arrested.[66] Leaders traveled to barracks across most of the South and Southeast to build up support.[67][68][69] The revolutionary central committee had a plan to enlist officers, which in the case of São Paulo began to be implemented in August 1923.[70] The conspirators arrested in Rio de Janeiro found considerable freedom and corresponded with their comrades in São Paulo.[71]

Meetings were held in the barracks themselves or in private homes;[70] festivities also provided cover for contacts.[33] In São Paulo, lieutenant Custódio de Oliveira's house on Vauthier Street, in Pari, served as the "Revolutionary HQ". Joaquim Távora, considered by João Alberto Lins de Barros as the "flag, brain and soul of the movement in its initial phase", lived there illegally. The meetings were attended, among others, by major Cabral Velho, inspector of Caçapava's 6th Infantry Regiment, captain Newton Estillac Leal, quartermaster of the 2nd Military Region, and lieutenants Asdrúbal Gwyer de Azevedo and Luís Cordeiro de Castro Afilhado, from the 4th Battalion of Caçadores.[72] Custódio de Oliveira also rented a house on Estrada da Boiada,[h] where rebel plotters hid weapons stolen from military units.[73]

Other articulations took place in Travessa da Fábrica, in Sé, the residence of deserters Henrique Ricardo Holl and Victor César da Cunha Cruz.[74] A unit of intense activity was the 4th Regiment of Mounted Artillery (RAM), from Itu, commanded by major Bertoldo Klinger, an officer of great prestige, who even agreed to assume a role in the revolutionary general staff.[33] On 23 December 1923, his superior, general Abílio de Noronha, commander of the 2nd Military Region, questioned the news of a secret meeting in the unit; in response, he was assured that all officers were dispersed for the Christmas and New Year holidays.[75] The general wanted to be impartial and chose not to pursue fugitive officers living clandestinely within his jurisdiction.[76]

Plotters "studied" several senior officers in the Public Force.[77] Since 1922, tenentism had already influenced officers of this institution, who added their own demands to the movement, such as the equalization of salaries with that of army officers. The great asset of the tenentists in São Paulo was the support of major Miguel Costa, inspector of the Public Force's Cavalry Regiment,[78] a prestigious figure within and outside the institution and a friend of several army officers.[79] Costa provided blueprints for barracks and public buildings, taking an active part in planning the occupation of the city.[78]

To lead the revolt, the prestige of an older officer was needed, a role formerly played by marshal Hermes da Fonseca in 1922.[80] Due to the post-1922 purges, the high-ranking officer corps on active duty no longer had rebel sympathizers. The officer they found was retired, general Isidoro Dias Lopes, who fulfilling their conditions: he was prestigious, uninvolved in 1922 and had the political ability to win civilian trust. Other names considered were the retired officers Augusto Ximeno de Villeroy, Odílio Bacellar Randolfo de Melo and, on active duty, Bertoldo Klinger and Miguel Costa.[81] Conspirators in Rio de Janeiro considered Isidoro oblivious to the situation and preferred Klinger.[82]

Sergeants and civilians

[edit]

Historiography highlights lieutenants and senior officers in the revolt,[14] stating, for example, that revolutionary propaganda was only made among the officers; from then on, sergeants, corporals and soldiers would only need to obey.[83] However, the criminal trials opened after the 1924 revolt show sergeants within the conspiratorial nucleus.[84] In this trial, sergeants were the majority of the military personnel indicted (59%) and convicted (47%); lieutenants are in second place. On the other hand, for the court, the lower ranks were accomplices, not heads of the plot.[85] The sergeants' defenses excused participation in the rebellion as simple obedience to commanders' orders, sometimes by coercion, but promotions received by many within the revolutionary army suggested an active participation.[86]

The movement was a military one, articulated from within the units, but because it aimed at power, it was of interest outside the barracks. Plotters contacted a number of civilians and counted on them to support their uprising after its outbreak in the military. This had difficulties, as plotting outside the military was riskier and there were prejudices against civilians. Defenders of this approach argued the presence of civilians is what would legitimize the movement and distinguish it from a mere barracks uprising.[87][88]

Despite the tenentists' criticism of professional politicians, there was an alignment of interests with the Republican Reaction, whose leader, Nilo Peçanha, defended the 1922 rebels and had several meetings with Isidoro.[89][90] An attempt was made to co-opt some dissidents from the São Paulo elite, such as Júlio de Mesquita and Vergueiro Steidel, but they did not want a revolution, much less one made by elements foreign to their class.[8][91] To garner support among workers, Isidoro used Maurício de Lacerda and Everardo Dias as intermediaries.[92] Plotters approached anarchist José Oiticica, socialist Evaristo de Morais and the Brazilian Cooperative Syndicalist Confederation.[93]

Military planning

[edit]

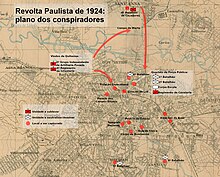

Despite the improvisations in its execution, the 1924 uprising was planned in detail and at length.[94] The conspirators took stock of the support across different units and classified them on maps as "friendly", "helpful", "easy to defect" and "enemy" forces. Under strict deployment schedules, these forces would concentrate at strategic points, controlling or destroying rail, telegraph, and telephone connections. The war would be violent and decisive; according to the plan, "cunning and mobility will be the preferred weapons".[95] As long as the forces were outnumbered, they would avoid direct combat.[96]

Outside São Paulo, the movement was expected in Minas Gerais, Paraná, Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul, with isolated support in Mato Grosso, Goiás and Rio de Janeiro.[97] In Paraná, Juarez Távora estimated the defection of 80% of the garrison, with enough officers to dominate the state, sympathy from the soldiers and civil support.[98] The 1st Military Region as a whole, in Rio de Janeiro, was considered hostile,[43] but there were written orders for the unit in Valença.[96] For logistical reasons, there was no plan for a revolt in northern Brazil.[99]

The plan stated that "the revolutionary movement will begin with the military takeover of the city of São Paulo, which must necessarily be consummated in a few hours". Participating units would be few, all from the city and the surroundings, to allow a quick and unexpected coup, leaving the loyalists without reaction.[100][101] The next major objective would be Barra do Piraí, in the interior of Rio de Janeiro,[102] to which a vanguard commanded by Joaquim Távora would hurry before dawn.[103] It would consist of a battalion of 550 men from the 6th Infantry Regiment, from Caçapava. Reinforcement platoons would stay at the Cruzeiro and Barra Mansa junctions. One company would be deployed beyond Santana station, and another to Entre Rios. With the help of civilian elements, telephone and telegraph connections to Petrópolis and Além Paraíba would be cut. In 24 hours, the rebels would gather 3,870 men in Barra do Piraí; in 36 hours, that would be 5,494. They would be in control of the Serra do Mar gorges, through which the Central, Auxiliar, Leopoldina and Oeste railroads passed. The Federal District would be isolated, but the plan did not clarify how it would be occupied.[104]

On other fronts, rebel units were expected to reinforce the offensive against Rio de Janeiro,[105] or at least distract the government.[97] To avoid a loyalist amphibious invasion, it would be necessary to occupy São Francisco do Sul, Paranaguá and Santos, or at least the Serra do Mar between Santos and São Paulo. In Rio Grande do Sul, the objective would be to prevent loyalist reinforcements from Porto Alegre to São Paulo.[54][105]

Date setting

[edit]

Through 1924, conspiracy leaders met several times in Jundiaí and São Paulo to set starting dates for the movement. This definition, and the compromises of who would go first, were complicated.[58] On 24 February, a faction led by Joaquim Távora advocated an early date, while another faction, represented by Bertoldo Klinger, considered the action premature. Távora's faction prevailed.[106]

The chosen date, 28 March,[107] would allow them to react to the imminent federal intervention in Bahia, where it would even have the support of governor J. J. Seabra.[54] According to one of the police documents, Seabra himself financed the conspirators.[108] But discussing collective decisions was very difficult, either because of inexperience or fear of repression.[15] The plan had to be postponed due to Klinger, who withdrew from the conspiracy, and doubts about the loyalty of the 4th Infantry Regiment.[109] To make matters worse, Klinger wrote a letter to Curitiba denying his participation and saying that there was nothing concrete in São Paulo. This was a disaster for the conspiracy in Paraná; according to Juarez Távora, the damage was doubled, as troops from Paraná would later come to fight the rebels.[98] Seabra lost his government in Bahia and Nilo Peçanha died on 31 March, further dismaying the conspiracy.[110] Without reliable support to the south, efforts were concentrated in São Paulo.[111]

By this time, rumors of the revolt had already reached general Noronha,[75] who demanded pledges of loyalty from his commanders.[58] Meanwhile, the conspirators set new dates, but did not use any due to lack of guarantees from one or another unit.[58][i] The date of 26 June was canceled due to the arrest of several fugitives in Rio de Janeiro. The surveillance of security agencies was increasingly stronger.[112] The plotters almost lost two units, the 2nd Pack Artillery Group and the 5th Battalion of Caçadores, as the removal of their commanders was requested by Abílio de Noronha to the Ministry of War on 28 June. Before it was carried out, the revolt broke out.[113]

On 30 June, Joaquim Távora put the conspirators in São Paulo on alert, warning them of the imminent arrival of "Severo" (Isidoro).[91] Rumors of an uprising in Rio de Janeiro emerged on 2 July, but these were just inspections and transfers of military personnel to break up the conspiracy.[93] On the same day, major Carlos Reis, former head of personal security for Artur Bernardes, came to São Paulo on a special mission. General Estanislau Pamplona, artillery commander in the state, ordered the Quitaúna batteries that the exercises outside the barracks should not last more than two hours and should not come closer to São Paulo than the neighborhood of Pinheiros.[112] On 3 July, the revolutionary high command set the start date at zero hour on the 5th.[112] This date, chosen in desperation, took advantage of the symbolism of the anniversary of the 1922 revolt.[58] On the night of 4 July, Carlos de Campos conferred with army and Public Force officers to unify the diverse information they had about the conspiracy.[114]

Urban warfare sets in

[edit]On 5 July there was no march to Rio de Janeiro,[115] and expected defections did not go as planned. Instead of a few hours, the fall of the city took four days, until governor Carlos de Campos withdrew to the Guaiaúna station, on the outskirts of the city. From a simple instrument in the plotters' plan, the city became a victim of urban warfare,[116] the most intense in the history of Brazil, with scenes reminiscent of the First World War.[117]

Execution of the plan

[edit]

At 04:30 in the morning of 5 July, general Noronha was notified that officers foreign to the garrison had moved 80 men from the 4th Battalion of Caçadores (BC), in Santana. The news was relayed to the state government and the Ministry of War.[118] The rebel force was led to Luz, headquarters of the main barracks complex of the Public Force, which was occupied, without resistance, with Miguel Costa's action from the inside. General Isidoro installed the revolutionary command in the general headquarters of the Public Force, and command of that corporation was assumed by Miguel Costa.[119][120] Detachments of the Public Force occupied the Sorocabana, Luz, Norte and Brás railway stations.[121]

In the early hours of this movement, rebel officers won several victories without firing a shot, but to their surprise, the loyalists did the same. General Noronha went to the headquarters of the 4th Battalion of the Public Force (BFP), in Luz, where he dismissed about 30 soldiers from the 4th BC — and they obeyed. Imprisoned loyalist officers were released. General Noronha was arrested by the rebels on his way back to his headquarters. But the damage was done: Joaquim and Juarez Távora, Castro Afilhado and other rebels, not realizing that the battalion had changed sides, entered the building and were arrested.[118][122]

In the words of Juarez Távora, "all the predictions laboriously discussed and weighed over several months would cruelly crumble, in a few hours, under the reality of insignificant unforeseen events".[123] Reinforcements from Quitaúna's 4th Infantry Regiment (RI) stood still by the absence of their internal contact, lieutenant Custódio de Oliveira, whose missions were delayed by the delay in Isidoro's arrival at the capital and by a cannon wheel that passed over his foot.[j] The conspirators forgot to cut telegraph and telephone communications, and the National Telegraph Bureau was occupied late and briefly. Lieutenant Ari Cruz, responsible for occupying the building, changed the guard to a company of the Public Force, not realizing that these "reinforcements" were loyalists.[124][125]

In Santos, plotters were left without guidance, also due to Isidoro's delay.[126] There were telegrams with orders for captain lieutenant Soares de Pina, commander of the School of Sailor Apprentices and naval reservist training in Santos, and for lieutenant Luis Braga Mury, of the 3rd Coast Artillery Group of Itaipu Fort, both in the Baixada Santista. The telegrams were intercepted and uprising's leaders, arrested before they even received them.[127][128]

In order to occupy the Government Palace, the conspirators relied on lieutenant Villa Nova — in reality, a government informant.[k] The Campos Elíseos Palace, residence of the state president, had a guard of just 27 men, but they were already warned and managed to repel a first occupation attempt, at 7:30 am.[129] A few hours later the rebels bombed the palace and, in the process, missed several shots and killed civilians in the vicinity.[130] Carlos de Campos insisted on staying in place, even when targeted by the enemy, and received a large number of visits.[8][131]

Results of the plan's failure

[edit]

After these setbacks, the rebel command decided to concentrate on fighting inside São Paulo.[115] This gave the federal government time to close the Itararé rail branch, the Baixada Santista and the Paraíba Valley. On 6 July, a Navy task force headed by the battleship Minas Geraes docked in Santos.[l] On the following day, loyalist reinforcements from Minas Gerais and Rio de Janeiro led by general Eduardo Sócrates gathered in Barra do Piraí. Sócrates established his headquarters in Caçapava, later transferred to Mogi das Cruzes, with a command post further on in Guaiaúna.[132] Army loyalists occupied São Caetano, between Santos and São Paulo.[133]

The fighting spread in São Paulo,[134] approaching the center, where the Anhangabaú valley and the Paissandu, Santa Ifigênia and São Bento squares were fought over. Scattered groups of fighters fought across the tops of buildings and hills.[135] In the 4th BFP, forty loyalists were still under siege.[131] Positions were won and lost, and the situation remained indefinite.[136] On 7 July, 70 loyalists attacked the southeastern flank of the revolutionary forces' heartland, the barracks of Luz. They were repulsed and besieged at the Light power plant, where they were still a threat.[137]

By the morning of 5 July, both sides had approximately 1,000 fighters.[138] Defections outside São Paulo, with a direct effect on the struggle, only occurred in some units of the 2nd Military Region, and even then, belatedly.[139] On the 6th, the loyalists received reinforcements from the army, but part of them (the 6th Infantry Regiment and a company from the 5th Infantry Regiment) joined the revolt. On 7 July, Further reinforcements from the army, the Public Force and a contingent of sailors arrived on the following day, but neither side achieved decisive numerical superiority.[138]

Consequences for the population

[edit]The morning of 5 July began like any other for civilians, but the sound of gunfire soon scared inhabitants of the center. Going out into the street in hot spots was too dangerous, and for safety, their residents stayed at home. Many were unable to reach their destination because of the fighting.[140] Trenches proliferated across the landscape;[141] in all, 309 were built in the city.[142] The population was unaware of the leaders and objectives of the revolt,[143] and it was difficult to identify which side fighters belonged to; Army and Public Force uniforms were of different colors, but there were rebels and loyalists in both corporations.[144] The setting of war in the center on 8 July was described by Estado de S. Paulo journalists Paulo Duarte and Hormisdas Silva as follows:[8]

We could not go down the slope of São João, towards the Red Cross, on Rua Líbero, because of the firefight that the forces of captain Guedes da Cunha sustained, from the top of the slope, in Praça Antônio Prado, with the rebel forces in Largo do Paissandu. Through São Bento square, impossible to pass. The fusillade there was more intense. We left the car in front of the Estado's office and, close to the walls, we ventured down the slope. A few bullets whistled around us.

Raw materials for the factories and foodstuffs from the interior could hardly arrive, as the train stations were occupied. As a result, factories came to a standstill and the distribution of goods was disorganized.[145][146] Almost everything stopped — most businesses, trams, schools and government offices. The phones and power supply still worked, but poorly.[8] Private vehicles were requested by both sides,[147] and civilians were forcibly recruited.[148] Few newspapers circulated, as paper, energy, and even employee movement were limited. Both the government and rebels censored the press.[149][150]

By 9 July, food shortages were already being felt.[151] Bakeries could not get flour, and milkmen turned back when they found trenches.[152] Bars, restaurants, and cafes operated behind closed doors for fear of stray bullets.[143] The population tried to stock as much food as possible,[152] but warehouses only accepted payment in cash,[151] and the federal government, fearing a run on the banks, declared a holiday until the 12th.[153]

Withdrawal of the state government

[edit]

In Campos Elíseos, the rebels conquered positions closer to the government's palace on 7 July and on the next day carried out a new, more effective bombardment. Advised by general Estanislau Pamplona to withdraw to a safer location, governor Carlos de Campos went to the Pátio do Colégio complex of government buildings, where police and sailors were concentrated.[135] This place was equally harassed by rebel artillery, which did not know of the governor's decision, but noticed the concentration of high-ranking officers. Oswald de Andrade mocked the situation: "for the first time in military history, instead of the bullet looking for the target, it was the target that looked for the bullet".[154]

The governor again withdrew, this time to the Guaiaúna railway station, in Penha, the last of the Central do Brasil that still communicated with Rio de Janeiro. It also had loyalist reinforcements commanded by general Eduardo Sócrates.[8] The governor was housed in a special locomotive belonging to the railroad administration,[155] which served at the same time as a mobile headquarters and provisional seat of the state government.[156]

By this time morale in the rebel leadership was at an all-time low. General Isidoro, noting the troops' exhaustion and fearing mass desertions, wanted to withdraw the entire revolutionary army to Jundiaí. Miguel Costa insisted on continuing the fight in the urban terrain to which the troops were accustomed. Isidoro ordered the withdrawal for the morning of 9 July, but Miguel Costa spent the night organizing the defenses. He wrote a letter to the governor, taking full responsibility for the uprising and asking for amnesty in exchange for his surrender. If his conditions were not accepted, he would fight to the end. But there was no one to receive the letter; on the morning of the 9th, the government's palace was empty. Its ruins soon filled with curious folk.[154][157]

Not only the governor, but also loyalist forces abandoned their positions or surrendered.[145][158] Isidoro, although victorious, considered resigning, resentful of Miguel Costa's insubordination, but the latter convinced him to remain at the head of the movement.[159] The rebels celebrated this turn of events,[154] considered by Isidoro to be a work of chance rather than a military feat.[159] Many years after the conflict, the decision to withdraw was still controversial; the rebels "were so certain of defeat, and yet they received, on a silver platter, the target that they considered unattainable".[160] According to Abílio de Noronha, loyalist commanders abandoned their subordinates, causing a disorderly retreat.[161]

Occupation of São Paulo

[edit]

After the departure of the state government, for a moment the city appeared to return to normality,[143] as hostilities were momentarily interrupted. The rebels did not take advantage of their enemies' low morale at the time of withdrawal and did not carry out their offensive plans.[162] If there was any illusion that the city would function normally, leaving them to deal only with the military front, it was shattered.[163] The city was bombed, the population looted the warehouses and fires consumed the factories. In addition to resisting the new loyalist offensive, the revolutionary command had to deal with the suffering of the population and reorganize the government, ceding responsibilities to civilians.[164]

Power vacuum

[edit]

General Isidoro proclaimed himself head of a "provisional government".[165][166] The state government was expelled from its headquarters, but this was not the original objective of the revolutionaries; if the Campos Elíseos Palace had been occupied without resistance, they would possibly have kept Carlos de Campos in power. General Isidoro declared in a manifesto that the revolution had no regional or personal objectives; the movement was solely against the federal government. Thus, mayor Firmiano de Morais Pinto was kept in office.[167] His responsibilities increased, filling the gap left by the state government.[168] This attitude contrasted with that of the municipal legislature, whose councilors did not meet at any time during the conflict.[169]

Respecting the mayor's term showed weakness, but allowed the rebels to focus their attention on the military front.[170][171] More than a tactical maneuver, the decision can be interpreted as coherence.[172] Firmiano Pinto was tasked with offering Fernando Prestes de Albuquerque, vice-president of São Paulo, to take the place of the governor expelled from Campos Elíseos. Prestes replied that "he would accept the government transmitted by Dr. Carlos de Campos by his own free will and never by the hands of the revolutionaries"; the mayor agreed. This refusal was no surprise; the vice-president was a powerful coronel from Itapetininga, with a known allegiance to the Republican Party of São Paulo, and he was organizing a loyalist resistance in the interior. The rebels then offered the government to José Carlos de Macedo Soares, president of the Commercial Association of São Paulo, in a triumvirate with lieutenant leaders, but he refused.[173][174]

Looting of stores

[edit]Living conditions continued to deteriorate:[175]

Countless dead and wounded enter the blood hospitals. Garbage accumulates in the streets. Filth reigns. Despite the fixed prices for foodstuffs, hunger prevails, like an immobilizing plague. (...) In various parts of the city, dead and abandoned horses are displayed. A pestilent smell invades the air, foreshadowing an epidemic, and tortures the nose...[176]

Starving, working-class families noticed the lack of policing.[177][178] On 9 July, a wave of popular looting of commercial establishments began in the farthest neighborhoods (Mooca, Brás and Hipódromo), later reaching the center.[179] The city's government recorded 61 looted establishments, 6 looted and set on fire, and 6 robbed throughout the month.[180] Almost all shops, emporiums, and warehouses were attacked.[179] The most affected companies were Sociedade Anônima Scarpa, Matarazzo & Cia, Ernesto de Castro, Nazaré e Teixeira, Motores Marelli, Maheifuz & Cia, Moinho Gamba, Moinho Santista, Reickmann & Cia and J.M. Melo.[181]

Oxen loaded onto a Central do Brasil train were released, slaughtered and quartered in the street.[179] In the factories and mills of the Matarazzo family, in Brás, Italian orators spoke during the sacking, calling the owners "usurers and exploiters of the people".[179] About this case, José Carlos de Macedo Soares reported that the crowd "carried every last board of the shelves, breaking the glass, making the scales, cabinets, display cases and counters unusable, everything was broken and carried away".[182]

The looting had a moral dimension, expressing popular indignation at rising prices and previous discontent with their bosses.[183] Some of the industries that suffered the greatest looting, such as Matarazzo and Gamba, had experienced strikes in January and February of the same year.[184] Looting was also a way to satisfy hunger and, for some, to make easy profits. Witnesses saw all sorts of goods being carried, such as crockery, silk stockings, typewriters, and electrical wires, not just food.[185][182] Even the journal A Plebe, a periodical with a less negative view of the looting, noted "many people who took advantage of the occasion without being in need, as well as a lot of wastage and spoilage of food".[186]

Both men and women participated, and little coordination and planning was required.[187] It is not known for sure who started the lootings; they may have been a spontaneous movement, but some sources attribute their initiation to João Cabanas, a lieutenant in the revolutionary army.[188] In his account, Cabanas claimed to have caught and shot two looters in the act.[189] Finding the Municipal Market surrounded by an angry crowd, he ordered the doors to be broken down and the goods distributed to the poor, taking care only to avoid abuse, which was not entirely possible. According to the judicial trial, the rebels began looting to supply their troops, and the people seized the opportunity.[190] There is also a report of a popular sack supported by the loyalist army in Vila Mariana.[191]

In this sense, there was acquiescence from the rebels with the attacks on commercial buildings,[190] but the leaders distanced themselves from any looting or depredations,[192] promising to arrest the rioters, and at the same time, demanding that merchants not exaggerate in prices.[191] Cavalry from the Public Force patrolled the streets, and Army soldiers guarded banks, large export companies, and diplomatic representations.[193] The Revolutionary Police Command, headed by major Cabral Velho, demanded the return of the looted items, threatening to arrest those responsible based on photographs and denunciations.[194]

New frontlines

[edit]

Much of the country's combat strength was sent to São Paulo. Loyalist reinforcements from the Army and the Public Forces, coming from several states, expanded the loyalist army to 14–15 thousand men by mid-month, armed with the most modern equipment of the Armed Forces. The rebels were outnumbered by five to one, with at most 3 to 3,500 effective fighters. The loyalists organized themselves into a division commanded by general Sócrates and composed of five infantry brigades and one divisional artillery brigade.[195][196] The rebels divided into four defensive sectors and two flank guards.[197]

The loyalists came from Rio de Janeiro, via the Central do Brasil railway, and from Santos via the São Paulo Railway, conditioning their distribution in a semicircle extended from Ipiranga, to the south, to Vila Maria, to the east.[198] The front line thus fell in working-class neighborhoods on the periphery.[199] According to general Sócrates, enemy defensive positions were strong. General Noronha had the opposite opinion, emphasizing the precariousness of the street barricades.[200] But several sources emphasize the defensive value of some points, notably factories.[m]

At Ipiranga, the Arlindo brigade left its left flank exposed to an attack from Cambuci and Vila Mariana on 10 July, but managed to repel the offensive.[201][202] With its right flank secured by advances from the Tertuliano Potiguara brigade in Mooca, the Arlindo brigade occupied positions in Cambuci and Liberdade on 14 July.[203] Meanwhile, on the banks of the Tietê River, the Florindo Ramos brigade had its advance blocked by the defenders of the Maria Zélia Factory.[204]

According to Abílio de Noronha, coordination between the loyalist brigades was very precarious, leaving flanks exposed to rebel attacks. Applying the principle of concentration of forces, the rebels kept a large part of their strength as a motorized reserve.[196][205] Thus, on 14 July, the Potiguara brigade advanced too far, exposed its flanks and was forced to retreat. This exposed the flanks of the Telles and Arlindo brigades, respectively to its right and left. By 16 July, the Arlindo brigade's gains were reversed.[203][206] During this counteroffensive, the rebels suffered a great loss: Joaquim Távora was mortally wounded in the attack on the barracks of the 5th BFP, in Liberdade.[207]

Loyalist bombardment

[edit]

Artillery fire was the main cause of death in the conflict.[208] The government had a material advantage in this armament, with numerous, more modern and larger caliber guns. Against about 20 Krupp guns of 75 and 105 millimeters, the loyalists had more than a hundred Krupp, Schneider and Saint-Chamond guns, including 155 millimeter howitzers. The insurgents' artillery could not compete with the government's longer-ranged guns, well positioned on the ridges around the city.[5][209]

On 8 to 9 July, loyalist artillery attacked Luz, where the revolutionary headquarters was located, and Brás. The bombardment intensified from the 10th to the 11th, also hitting Mooca and Belenzinho. Many other neighborhoods were hit throughout the month, such as Liberdade, Aclimação, Vila Mariana,[210] Vila Buarque, Campos Elíseos,[211] Paraíso[212] and Ipiranga.[213] The hardest hit were Luz and the working-class neighborhoods of the east,[214] but the wealthier residential neighborhoods, while much less affected, were not spared.[215] The bombardment was continuous, day and night;[216] on 22 July, 130 artillery shells were fired per hour.[217]

Densely populated areas devoid of military targets were hit. The shells collapsed walls and roofs, destroying the houses. Terror dominated the population, who took refuge in cellars.[218] Civilians were the majority of those killed.[210][219] An emblematic case was the Teatro Olympia, in Brás:[220] although located half a kilometer from the nearest trench, it was hit on the 15th, burying dozens of homeless families.[221][222] The government did not seem to mind the collateral damage.[223] The rebels also showed little regard for civilian casualties,[224] but caused much less damage.[225]

Many industries were damaged, such as Companhia Antarctica Paulista, Biscoitos Duchen, and Moinhos Gamba.[226] Most shocking was the symbol of São Paulo's industrial power, the Cotonifício (Cotton Factory) Crespi,[227] which housed rebel troops and displaced families. It was set on fire as many as five times and partially destroyed.[220][228] By the 22nd, plumes of smoke were visible for miles around.[229] Fires consumed several parts of the city, attributed to both bombing and looting.[145] The Criminal Court was also set on fire, which may have been a destruction of records, unrelated to the bombing.[194]

Militarily, bombing may have been a way to progressively wear down the enemy and spare loyalist troops.[230][231] However, it had little effect on the defenses;[n] Abílio de Noronha concluded it was an attack at random, without regulation and correction of fire, disobeying the principles of artillery.[232] The Minister of War condemned his enemies for "fighting under the moral protection of the civilian population",[233] but promised that he would not cause unnecessary material damage.[234] Carlos de Campos was tougher in his rhetoric: "São Paulo would rather see its beautiful capital destroyed than legality in Brazil destroyed".[235]

Historians discuss the bombing as deliberate violence against the civilian population, a "terror bombing" or "German-style bombing".[236][210][237][238][239] This could be a way to pressure the rebels to leave the city, hastening a capitulation,[240][238] a return to the brutal methods used in the Canudos and Contestado wars,[241] and/or a punishment of the workers for their association with the rebels,[242][222] or for the looting.[243]

International law of the period condemned indiscriminate bombing, without regard for civilians, as a war crime. In the years after the revolt, the legality of the decision was hotly debated among jurists.[244][245]

Population exodus

[edit]

Fleeing the violence, the population, especially in the most bombed regions, moved en masse to neighborhoods farther from the center, such as Casa Verde, Lapa, Perdizes and Santo Amaro, and to the interior of the state.[246] The prefecture registered 42,315 people sheltering in hospitals, schools, churches and other institutions.[247] Many other evacuees stayed in tarpaulin barracks.[8]

257,981 refugees were counted by the prefecture, about a third of the city's 700,000 inhabitants;[152] some figures go up to 300,000 refugees.[175] Comparing the population of the municipality in the 2010s, with 11 million inhabitants, there would be 4 million refugees.[o] The main destination was Campinas, with smaller flows to Jundiaí, Itu, Rio Claro and even more distant municipalities such as Bauru.[248][249] The rich preferred their farms or Santos.[250] Cities such as Campinas began to have supply problems.[251]

Refugees left by any means possible: in automobiles, carts, wagons or on foot.[252] The main means of transport was the railroad, used by 212,385 refugees, according to the prefecture.[152] Rail connections with the interior were re-established on 12 July, but they were irregular and risky.[251] Families crowded into the Luz and Sorocabana stations, and the trains left with refugees hanging from the railings outside the wagons.[253]

Relations with society

[edit]Economic elite

[edit]

The bombings, fires and looting caused plenty of losses to São Paulo's economic elite, who acted actively to defend their properties and prevent the collapse of the city. The rebels overthrew political power (i.e. the governor), but they still had to deal with economic power — the Industrial Center, Rural Society, Association of Banks and Commercial Association. The latter declared support for Carlos de Campos at the start of the revolt, but cooperated with the rebels when they became the real authority in the city.[242][254]

The looting was a major factor in friction between the rebels and the bankers, farmers, industrialists, and merchants.[255] Policing the streets with soldiers who could have been on the front lines was not in the interest of the rebels. On 10 July, general Isidoro attended a meeting of the Commercial Association, where it was decided that the City Hall would organize a Municipal Guard[256][257] and a Supply Commission.[258] The Guard was organized with 981 volunteers, among them more than a hundred students from the Faculty of Law of the University of São Paulo, the "Academic Brigade".[259] These measures alleviated the problem of looting.[260]

Formal power rested with the mayor, but the most important decisions came to be taken at Association meetings.[261] Its president, José Carlos de Macedo Soares, developed a cordial relationship with general Isidoro and took on a leading role among "citizens in good standing",[8] who the courts later praised for performing "services to the community, performing functions essential to the maintenance of order, in the absence of legally constituted authorities".[88] Another important example in this group was Júlio de Mesquita. He was critical of the Republican Party of São Paulo,[8] but his collaboration and that of other representatives of the elite, much criticized by more loyalist elements such as vice-mayor Luiz de Queirós, did not mean siding with the rebels.[254]

On 11 July, the Board of the Association of Banks discussed an extension of the holidays with general Isidoro. There was no financial disconnection; financial operations were not under the control of the rebels, who allowed bankers to negotiate with the federal government. Industrialists and traders also wanted a moratorium, which would consist of extending the deadlines for paying off bank commitments, but this measure was only granted after the end of the conflict. The concern was the difficulty of paying wages to workers, which could result in disturbances.[262] The scarcity of money was partly overcome by the circulation of bonds issued in the name of the revolution.[263]

Workers

[edit]

The participation of workers in the revolt, in different forms, was remarkable.[264] At least 102 railroad workers collaborated with the rebels' logistics in the interior.[265] In the railway workshops in São Paulo, other workers, directed by foreign technicians, improvised bombs, grenades, armored cars and even an armored train.[266][267][268]

After 20 July,[269] up to 750 immigrants enlisted in the revolutionary army, forming three foreign battalions (German, Hungarian, and Italian).[270] The volunteers were mostly factory workers who had lost their wages due to the shutdown of factories. Some were World War I veterans with valuable experience for the war in São Paulo.[269] Foreign "mercenaries" were one of the most controversial elements of the revolt;[271] the loyalist press labeled them a threat to the Brazilian population and associated them with the immigrants' reputation in Brazil for political radicalism.[272]

In general, workers joined in an improvised way, as simple residents and not as members of class organizations.[273][274] Some rallies called by individuals of other classes tried to mobilize this segment of the population,[275] which, in turn, tried to include their agendas in the demands of the revolt.[276] In organized civil society, the greatest support, even if only moral,[277] came from guilds, unions, and associations dominated by anarchists and libertarian socialists in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. On 15 July, some of these militants pleaded for their sympathy in a "Motion by workers' militants to the Revolutionary Forces Committee", noting that the rebels' manifesto had given guarantees for the demands of the population.[186][278] In Rio de Janeiro, the typography of Antônio Canellas, a former leader of the Brazilian Communist Party, published the pro-revolt newspaper O 5 de Julho.[93]

Fears of revolution

[edit]

The war degraded workers' living conditions, and the tenentists' political program did not offer demands such as the minimum wage and the eight-hour workday.[275] Anarchists admitted not having the revolution they dreamed of, but they saw revolutionary potential in the process. Their objective would be "a revolution as close to ours as possible", in the words of the newspaper A Plebe, which was optimistic over the looting and flight of the elite "in fear of a popular revenge". Orators encouraging looting, and volunteering in the revolutionary army, would also be indications of this potential.[186] In 1925, the communists also considered the possibility of co-opting the tenentists' revolution,[280] but during the revolt in São Paulo, they still opted for prudence, neither supporting nor criticizing the movement.[278]

On the other side of the conflict, radicalization to the point of a revolution like the one that took place in Russia in 1917 was feared by the federal government, aware of the history of labor conflicts in São Paulo.[281] Within the city, social unrest, not just immediate damage, was what motivated the Commercial Association to maintain order and minimize the damage of war.[282] In the words of Macedo Soares, "the workers are already agitating and the Bolshevik aspirations are openly manifested. Later the unemployed will certainly attempt the subversion of social order".[166][283]

For this reason, the Commercial Association and other representatives of the elite demanded that the federal government suspend the bombing, and at the same time, warded off the tenentist leadership from the workers' movements, warning about subversion and civil war.[284][285] Under pressure, the leaders were divided. The involvement of wealthy civilians was welcome, while that of blue-collar workers was controversial; Isidoro was more conservative in this regard, and Miguel Costa was less so. As soldiers, the tenentists were part of an institution of state repression, and workers' involvement distorted what they understood as order. A more elitist tendency prevailed, and the movement paid more attention to merchants and political authorities than to workers' representatives.[286][287][288]

In the desired "revolution with order",[289] popular support could only come in favor of its political project in specific, or at least, without interfering in it. Therefore, recruiting foreign battalions was not a problem, but when the anarchists offered to form autonomous battalions, without military discipline and interference, they were refused by general Isidoro. According to tenente Nelson Tabajara de Oliveira, "this would distort the original motive of the movement"; "therefore, they were not interested in the presence of leftists in the fighting cadres, even if they came to reinforce the revolution".[186][288][p] Earlier, in planning the uprising, the Communists had offered to organize guerrilla warfare, and were similarly rebuffed.[290] Later in 1924, the communist Octávio Brandão blamed this attitude for the defeat, classifying it as petty-bourgeois, positivist and narrow-minded.[287]

Degree of popular support

[edit]

Plans for the revolt specified that "the people's material and, above all, moral support for the revolution is a very important factor for victory".[291] Although tenentism is considered primarily a military movement, civilian involvement in the revolt was extensive. Civilians accounted for 61% of those indicted in court for participating in the movement, against 29% of military personnel from the army and 9% from the Public Force.[292] Among them were many elements of the middle class, such as teachers, students, shopkeepers, and officials.[293]

Aside from these active participants, observers' opinions varied widely, ranging from approval to outright condemnation.[294] In the secondary literature, some sources present popular reaction as uncooperative or enthusiastic,[207][295] with minimal support to the rebellion.[296] Others describe popular support,[297][223][298][299] and even an increasing mass participation.[289] Reasons cited for the lack of support include the leadership's own lack of interest in negotiating with the proletariat,[296] and the need to requisition food from the population.[207] For the contrary thesis, the revolt attracted all sectors distressed by the political and economic situation,[300] convincing by ideological affinities and the moralizing character of the movement.[293] Loyalist bombing created antipathy to federal authorities.[301]

Supporting evidence is found in the declarations to the courts after the revolt,[293] and in several accounts of fraternization in the trenches.[302][299] According to shoemaker Pedro Catalo, "in any house that these soldiers asked for food, coffee or other emergency favors, they were met with sympathy and enthusiasm".[289] Isidoro was even praised in popular songs in viola caipira.[303]

In July, Macedo Soares assessed that the population "bitterly compares the generous treatment it has received from the revolutionaries with the useless inhumanity of the uninterrupted bombing".[279] Monteiro Lobato wrote in August that "the state of mind of the Brazilian people is one of open revolt", and the proof of this would be Carlos de Campos: "a government falls completely, destroyed in all its parts, and no one appears to defend it".[304][305] In an open letter to the governor, he and other prominent paulistas, including figures from the PRP, warned that "loyalism does not exist in private", and civil servants, merchants, industrialists and academics sympathized with the revolution.[306]

Humanitarian measures

[edit]

Public charity ensured the subsistence of part of the population.[307] Even before the creation of the Public Supply Commission, the Red Cross, the Nationalist League and other institutions already provided services to the population. The City Commission checked food, fuel and firewood stocks, fixed prices and organized the transport of food and population to safer areas of the city. The prefecture identified 182 aid stations, where 581,187 meals were distributed.[308] A representative traveled to Santos, but admiral Penido, who commanded the city, vetoed any food purchases.[309]

While the fires raged, the Fire Department was inoperative, as its members fought in the loyalist army and, after the withdrawal of the state government, they left the city or remained as prisoners. At the request of Macedo Soares, general Isidoro released these prisoners, and the City Hall managed to reorganize the service on 25 July.[259][310] Medical care took place at the Umberto Primo and Samaritano Hospitals, and Santa Casa de Misericórdia.[311] The public cleaning sector buried or incinerated the dead animals, while the City Hall's Hygiene Department organized the burials.[308] The bodies collected in the city were piled up at the Vila Mariana tram garage, where dozens of people inspected each corpse, looking for their missing family members. The number of bodies exceeded the gravediggers' working capacity and the supply of burial urns to the point that some were buried wrapped in sheets.[312]

The conflict broadens

[edit]Interior of São Paulo

[edit]

87 municipalities in São Paulo had a record of revolt, and another 32 had demonstrations of support. Of the municipalities with revolt, in 21 it started with the initiative of civilians. Local political elites belonged to the Republican Party of São Paulo and tended to support the government, to the point of organizing patriotic battalions to fight the revolt. But the municipalities were very dependent on central power, which left them helpless. The opportunity was great for local dissidents, many of whom joined the revolutionaries. The mayors and delegates of 35 municipalities joined the revolt or were replaced by "governors" appointed by the rebels.[313][314][315]

On 9 July, the rebels already controlled Itu, Jundiaí, Rio Claro and Campinas; the first three municipalities were dominated by local army units when they joined the revolt.[316] By itself, Campinas already had great value as a railway junction and economic base.[317] Alderman Álvaro Ribeiro, head of the municipal opposition, was appointed governor of the city and given authority to intervene in others.[318]

Three loyalist brigades were sent to cut the rebels' rearguard: general Azevedo Costa came from Paraná, João Nepomuceno da Costa from Mato Grosso, and Martins Pereira from Minas Gerais. In response, on 17–19 July the revolutionary command sent three detachments to the Sorocabana, Mogiana, Paulista and Noroeste railways.[319] In addition to these three, smaller groups of sergeants and civilian allies occupied several municipalities.[320] At the end of the month, the rebels occupied the triangle between São Paulo, Campinas and Sorocaba, as well as a cone towards Bauru and Araraquara.[319]

The most valuable objective was Bauru, an almost obligatory railway junction on the way to Mato Grosso, and where there was also strong local opposition.[321] On 18 July, the city was occupied by captain Muniz Guimarães and his improvised column, made up of volunteers enlisted along the way. There were no exhausting fights. 300 soldiers from the Public Force could have defended the city, but they had been sent away amid panic and rumors about Carlos de Campos leaving the center of the capital.[322] The Mato Grosso brigade, which could also have defended Bauru, would only arrive the following month, delayed by the precariousness of mobilization and the revolutionary sympathies of its officers.[323][324][325]

At Mogiana, lieutenant João Cabanas led an initial force of 95 men against general Martins Pereira's nearly 800 regulars.[326] But the loyalists spread their forces too thinly and acted passively, while Cabanas had an experienced troop, which he kept concentrated and constantly on the move, using psychological warfare to mislead the opponent as to their direction and manpower.[327][328] His contingent, which was nicknamed the "Death Column", was victorious in Mogi Mirim, on the 23rd, and Espírito Santo do Pinhal, on the 26th, frustrating Martins Pereira's intention to advance against Campinas.[329]

Only in Sorocabana were the loyalists victorious. Captain Francisco Bastos left the rebels in a positional defense, giving the loyalists plenty of time to organize.[330] General Azevedo Costa was reinforced at Itapetininga by three patriotic battalions organized by Fernando Prestes. On 19 July, he organized the Southern Operations Column or Southern Column, with which he sent a vanguard to Itu and another to São Paulo. En route to São Paulo, the second vanguard defeated strong resistance at Pantojo and Mairinque on 26–27 July.[331][332]

Parallel uprisings

[edit]

The São Paulo revolt was the propagating focus of a series of tenentist uprisings in other regions of Brazil,[333] collectively referred to as the "1924 uprisings"[q] or "1924 revolts".[334][335] Each had its own particularities.[336] These were not, however, the support expected by the São Paulo conspirators, but few, dispersed and unsuccessful outbreaks of rebellion.[337]

The parallel uprisings were a way to divert government reinforcements on their way to São Paulo, relieving pressure on the São Paulo rebels.[338] Several battalions of caçadores from the current North and Northeast regions received orders to embark for Rio de Janeiro, but only the 19th, from Salvador, got to fight in São Paulo.[r] The 20th, 21st, 22nd and 28th, respectively from Maceió, Recife, Paraíba (now João Pessoa) and Aracaju, were preparing to embark when the 28th rebelled on 13 July, and the others were redirected to fight it in Sergipe.[339] On the same day, boarding orders for the 24th, 25th and 26th, respectively from São Luís, Teresina and Belém, were cancelled.[340] New arrangements were made with the 26th and 27th, from Manaus, but these also rebelled, respectively, on the 26th and 23rd of July.[341]

An uprising in Pará quickly failed in combat with the State Military Brigade.[342] The Sergipe and Amazonas uprisings went further than the São Paulo one, installing new state governments.[343][344] Both movements were defeated in August, after the loyalist victory in the city of São Paulo.[345][346] In the case of Amazonas, the federal government had to send 2,700 soldiers to the North,[347] from battalions in the Northeast, Espírito Santo and Rio de Janeiro.[s]

Only in Mato Grosso did the plans of the conspiracy in São Paulo have a concrete result. The commander of the 1st Mixed Brigade himself, lieutenant colonel Ciro Daltro, may have delayed the movement to São Paulo to benefit the rebels. On 12 July, the 10th Independent Cavalry Regiment, in Bela Vista, revolted, but it was contained by the unit's sergeants.[348]

Loyalist victory in the capital

[edit]The fighting in the city of São Paulo lasted until the night of 27 July, when the rebels withdrew by train towards the interior. In Isidoro's assessment, it would still have been possible to resist for another ten or fifteen days inside the city.[349]

Final combats

[edit]

Each side resorted to novelties in military technology. Loyalist Military Aviation began flying over the city on 19 July. It operated little, but its bombings had a psychological impact. Naval Aviation stayed with the fleet in Santos. The rebels used requisitioned civilian planes, but only for reconnaissance and propaganda distribution.[350][351]

The Assault Car Company, with eleven Renault FT-17s, attacked the rebels in Belenzinho from the 23 July; there are reports of initial success, later mitigated by the lack of infantry support for these tanks.[352] Brazil's first attempt to build armor took place in workshops in rebel territory, but the resulting two cars were too heavy to move.[353] There was more success with an armored train, used in raids on loyalist positions in Central do Brasil until 26 July, when it was derailed by an artillery ambush.[354] On the São Paulo Railway, the Navy improvised railway artillery with cannons from the ships.[355]

On 23 July, after days of intense combat, loyalists captured two strongholds, Largo do Cambuci and the Antarctica Factory, in Mooca; on the other hand, their offensive at Vila Mariana was defeated.[356][296] The broad loyalist offensive resumed on 25 July, when the Military Brigade of Rio Grande do Sul approached another redoubt, Cotonifício Crespi.[357] The following day, the Public Force of Minas Gerais dominated the Hipódromo da Mooca, and on the next the Central do Brasil warehouse, already preparing to occupy the North Station.[358] In Brás, Cambuci and Liberdade, defensive sectors retreated.[359]

On 26 July, loyalist planes distributed bulletins from the Ministry of War over the city urging the population to leave the city as "to spare themselves the effects of military operations, which, in a few days, will be carried out". The mood of panic increased; in the interpretation of Macedo Soares, that was "the threat of a general bombardment, of complete destruction of the city, indistinct, without respite, over the built area". Even worse, for him, the 400,000 inhabitants left in the city had no way to get out.[233][360]

Negotiation attempts

[edit]Since the start of the loyalist bombing, welfare institutions, representatives of merchants and industrialists, and foreign diplomats had tried to negotiate a ceasefire. This intervention had humanitarian motives and, equally, interests at stake.[361][362] On 12 July, Macedo Soares, Júlio Mesquita, Dom Duarte Leopoldo e Silva, the Archbishop of São Paulo, and Vergueiro Steidel, president of the Nationalist League, sent the following telegram to the President of Brazil:[363]

We ask Your Excellency for charitable intervention to stop the bombardment against the defenseless city of S. Paulo, since the revolutionary forces agreed not to use their cannons to the detriment of the city. The commission does not have any political intention but exclusively compassion for the population of São Paulo.

Minister of War Setembrino de Carvalho replied that the moral damage caused by the revolt was much worse than the material damage to the city. He proposed that the rebels spare the population, leaving the city to fight in the open.[223][364] Another response came from general Sócrates, when asked by the consuls of Portugal, Italy, and Spain: he would spare the civilian areas, as long as the rebels indicated where their troops were.[200][365]

On 16 July, Macedo Soares communicated with general Noronha, a prisoner of the rebels, asking him to intercede with the president. The general agreed to be a go-between for an armistice and the next day he read Isidoro's demands. The first: "immediate handover of the Federal Government to a provisional government composed of national names of recognized probity and confidence of the revolutionaries. Example: Dr. Venceslau Brás". Noronha dismissed it completely; the resignation of Artur Bernardes, under these conditions, would be for him a "blow to national sovereignty by the edge of bayonets".[366]

In a new proposal on 27 July, the rebels, already on the verge of defeat, had a single demand, amnesty for the rebels of 1922 and 1924.[367] Macedo Soares wrote a letter to general Sócrates, arguing that "the victory of any of the fighting parties, if it is not immediate, will no longer save the State of S. Paulo and, therefore, Brazil, from the most desolate ruin". For him, the danger of social unrest was more serious than military rebellion, and so he requested a 48-hour armistice so that Abílio de Noronha could negotiate. Journalist Paulo Duarte delivered the letter in Guaiaúna, where it was read by Carlos de Campos. The governor, irritated, accused the negotiators of making common cause with the rebels and promised to increase the bombings.[368][369]

Rebels withdraw from the city

[edit]

On 27 July, the revolutionary high command took an unforeseen decision, but which seemed to be the only way to prolong the movement: withdraw the army from São Paulo, waging a war of movement in the interior.[370][371] In Mato Grosso, they still hoped to reinforce the movement with local sympathizers, or, at worst, to go into exile in Paraguay or Bolivia.[372] The only road to Campinas was about to be cut, trapping them in the capital,[373][374] where further combat would only result in the destruction of the rebels themselves and the population.[49] Negotiations failed,[375] and the only possibility of victory would be with new uprisings in Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais. The fighters were worn out, many of them wounded;[376] there are conflicting reports about troop morale.[t]

Pressure from the loyalist division was supposed to pin the rebels in combat, preventing a retreat, which is a laborious and risky military operation. Ordnance was loaded on trains starting at 14:00, but the troops withdrew at night, and loyalists had no night patrols or contact with enemy infantry. The revolutionary army escaped largely intact, with all its supplies; only a few elements of the southern detachment were left behind. The loyalists did not realize the withdrawal until the morning of 28 July. In Jundiaí, the South Column cut the road to Campinas at noon, but at 07:00 the last train had passed through Itirapina. A day's difference would have prevented the escape.[377][378][379]

At 10:00 on the 28th, Carlos de Campos reopened his office at the Campos Elíseos Palace.[380] The city's deoccupation celebrated with fanfare and military parades through the central streets.[381] According to Macedo Soares, the population received them coldly;[382] Monteiro Lobato compared the loyalist parades with the "German army entering Paris".[305] Several newspapers criticized the behavior of loyalist soldiers during the reoccupation,[383] and the anarchist press denounced the occurrence of rapes.[384] There are reports of looting of commercial stores by soldiers from the Public Forces of Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais.[385] Due to these accusations, the Public Force of Minas Gerais expelled 17 soldiers, but incorporated them again when an investigation concluded that they were innocent or inculpable.[386]

By the beginning of August, industries and services were back in business, numerous workers were clearing the rubble and the damaged buildings were being rebuilt. Scouts looked for corpses buried in backyards, squares and gardens, and families from the countryside, out of curiosity, visited the abandoned trenches.[387]

Continuation of the revolt

[edit]The rebels of 1924 went much further than those of 1922,[298] and the movements started in 1924 dragged on until 1927, as part of the Miguel Costa-Prestes Column.[388] But in this flight to the interior, the tenentes distanced themselves from Rio de Janeiro, which they never managed to threaten.[53]

From São Paulo to the Paraná River

[edit]

The revolutionary army arrived in Bauru on 28 July, where it was reorganized into three brigades commanded by Bernardo de Araújo Padilha, Olinto Mesquita de Vasconcelos and Miguel Costa.[389] The Noroeste Railroad's passage to Mato Grosso, in Três Lagoas, was already blocked by the loyalists. The only option was the Sorocabana branch, through Botucatu to Presidente Epitácio.[379] A detachment was sent to Araçatuba, in the Northwest, to delay the Mato Grosso brigade. The battalions of Juarez Távora and João Cabanas were defending the rear during the passage through Botucatu, when they were attacked at the top of the mountain range by the loyalist vanguard. General Malan d'Angrogne recorded heavy losses on the defenders (73 prisoners), but they ensured the escape of the bulk of their army.[390]

The rebel vanguard stopped in Assis on 5 August, when a ceremony celebrated one month of the revolt and the newspaper O Libertador was published.[391] The following day it occupied Porto Tibiriçá, in Presidente Epitácio, on the banks of the Paraná River, imprisoning several vessels and a small loyalist contingent.[392]

Rearguard actions would still take 42 days along the 1,200 kilometers of road, on which several battles were still fought against pursuing loyalist columns, notably in Santo Anastácio. This mission fell to the "Death Column", which systematically destroyed the railway infrastructure on the way to delay the loyalist advance. This was a military necessity, but created controversy in the press.[393] João Cabanas became famous and infamous, accused of numerous depredations, threats and murders in the police investigation of the rebellion. In his writings, Cabanas prided himself on the terror his name created among his opponents, but claimed to have harshly punished, even with shootings, crime among his soldiers.[394]

Battle of Três Lagoas

[edit]

On the banks of the Paraná river, the revolutionary command was divided over strategy: colonel João Francisco wanted to go downstream and, in western Paraná, connect with officers committed to the movement in Rio Grande do Sul. Isidoro preferred to go up to Três Lagoas and invade Mato Grosso.[395][396] There, João Cabanas believed in the viability of a "Free State of Brasilândia", financed by tariffs on the export of yerba mate. Easily defended by the Paraná River, the rebels would have time to rebuild their forces and reconquer São Paulo,[397] or at least force the government to negotiate.[398]

The invasion force landed on 17 August, under the command of Juarez Távora,[399] with 570 men, including a shock force composed mainly of foreigners.[400] But Três Lagoas was better defended than they thought. The Mato Grosso loyalists had withdrawn the troops sent to Bauru to defend their own territory, and were reinforced by colonel Malan d'Angrogne and his column from Minas Gerais.[401][402] What has been called the bloodiest battle of the São Paulo revolt took place on 18 August, with the invaders defeated with heavy losses by the 12th Infantry Regiment and the Public Force of Minas Gerais.[403][404] However, the loyalists had concentrated too much forces to the north, and the way to Paraná was left open.[405]

Link with the Rio Grande do Sul rebels