Running Springs, California

Running Springs | |

|---|---|

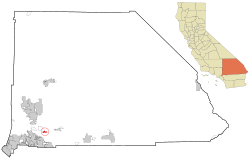

Location in San Bernardino County and the state of California | |

| Coordinates: 34°12′28″N 117°6′30″W / 34.20778°N 117.10833°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | San Bernardino |

| Area | |

• Total | 4.213 sq mi (10.912 km2) |

| • Land | 4.204 sq mi (10.889 km2) |

| • Water | 0.009 sq mi (0.023 km2) 0.21% |

| Elevation | 6,109 ft (1,862 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 5,268 |

| • Density | 1,253.1/sq mi (483.8/km2) |

| Demonym | Running Springser |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| ZIP code | 92382 |

| Area code | 909 |

| FIPS code | 06-63316 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1661346 |

Running Springs is a census-designated place (CDP) in San Bernardino County, California, United States. The population was 5,268 at the 2020 census, up from 4,862 at the 2010 census. Running Springs is situated 17 miles west of the city of Big Bear Lake.

Running Springs is home to the 3,400-acre National Children’s Forest, which offers interpretive programs, educational tours and more.[2][3] Snow Valley Mountain Resort was established here in the 1920s and was the first ski resort in the San Bernardino Mountains.[4][5]

History

[edit]The first people to settle here were the Serrano people (“mountain people”). They got their name from Spanish priest Father Garces in 1776, but called themselves Yuhaviatam (“people of the pines”). Numerous mortar holes can be seen throughout the area, made by the Serranos grinding acorns into meal. Native Americans settled here due to the rich natural resources. They gathered acorns and herbs, also hunting deer, rabbits and other wildlife.[6]

Running Springs was originally known as Hunsaker Flats, named for Abraham Hunsaker, an early member of the Mormon Battalion. The area was developed after improvements to the state highways in the 1920s.[7]

Geography

[edit]Running Springs is located at 34°12′28″N 117°6′30″W / 34.20778°N 117.10833°W (34.207739, -117.108285).[8]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the CDP has a total area of 4.2 square miles (10.9 km2), 99.79% of it is land and 0.21% is water.

Demographics

[edit]2010

[edit]At the 2010 census Running Springs had a population of 4,862. The population density was 1,154.0 inhabitants per square mile (445.6/km2). The racial makeup of Running Springs was 4,325 (89.0%) White (79.8% Non-Hispanic White),[9] 23 (0.5%) African American, 47 (1.0%) Native American, 50 (1.0%) Asian, 6 (0.1%) Pacific Islander, 146 (3.0%) from other races, and 265 (5.5%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 695 people (14.3%).[10]

The whole population lived in households, no one lived in non-institutionalized group quarters and no one was institutionalized.

There were 1,944 households, 611 (31.4%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 1,026 (52.8%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 171 (8.8%) had a female householder with no husband present, 106 (5.5%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 114 (5.9%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 38 (2.0%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 477 households (24.5%) were one person and 140 (7.2%) had someone living alone who was 65 or older. The average household size was 2.50. There were 1,303 families (67.0% of households); the average family size was 2.99.

The age distribution was 1,119 people (23.0%) under the age of 18, 375 people (7.7%) aged 18 to 24, 1,157 people (23.8%) aged 25 to 44, 1,672 people (34.4%) aged 45 to 64, and 539 people (11.1%) who were 65 or older. The median age was 41.7 years. For every 100 females, there were 105.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 103.4 males.

There were 3,729 housing units at an average density of 885.1 per square mile, of the occupied units 1,419 (73.0%) were owner-occupied and 525 (27.0%) were rented. The homeowner vacancy rate was 5.3%; the rental vacancy rate was 12.6%. 3,450 people (71.0% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 1,412 people (29.0%) lived in rental housing units.

According to the 2010 United States Census, Running Springs had a median household income of $59,111, with 9.3% of the population living below the federal poverty line.[11]

2000

[edit]At the 2000 census there were 5,125 people, 1,903 households, and 1,366 families in the CDP. The population density was 1,286.1 inhabitants per square mile (496.6/km2). There were 3,686 housing units at an average density of 925.0 per square mile (357.1/km2). The racial makeup of the CDP was 87.7% White, 0.5% African American, 1.7% Native American, 0.9% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 4.1% from other races, and 5.1% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 11.1%.[12]

Of the 1,903 households 35.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 56.2% were married couples living together, 10.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 28.2% were non-families. 21.5% of households were one person and 5.3% were one person aged 65 or older. The average household size was 2.61 and the average family size was 3.04.

The age distribution was 27.4% under the age of 18, 7.4% from 18 to 24, 28.8% from 25 to 44, 27.6% from 45 to 64, and 8.7% 65 or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females, there were 102.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 102.3 males.

The median household income was $50,524 and the median family income was $56,855. Males had a median income of $45,172 versus $34,492 for females. The per capita income for the CDP was $22,231. About 7.0% of families and 8.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 7.7% of those under age 18 and 9.9% of those age 65 or over.

Government

[edit]In the California State Legislature, Running Springs is in the 19th Senate District, represented by Republican Rosilicie Ochoa Bogh, and in the 34th Assembly District, represented by Republican Tom Lackey.[13]

In the United States House of Representatives, Running Springs is in California's 23rd congressional district, represented by Republican Jay Obernolte.[14]

Surroundings and economy

[edit]Running Springs is a mountain community in the San Bernardino Mountains. It is an inholding in the San Bernardino National Forest. Situated at the junction of State Route 18 and State Route 330, it is a major gateway to the mountain communities of Lake Arrowhead, Arrowbear, Green Valley Lake, and Big Bear and is the closest community to Snow Valley Mountain Resort. It lies some 16 miles (26 km) northeast of the city of Highland, California, up State Route 330, at an elevation of 6,080 feet (1,850 m). While there is no primary industry in Running Springs, there are service industries geared to the tourism market, as the San Bernardino National Forest is a year-round tourist destination.

Additionally, Running Springs, together with surrounding communities, form a bedroom community for commuters who are employed in San Bernardino.

Running Springs is a member community of the Rim of the World, an inhabited stretch of the San Bernardino Mountains and wholly contained in the San Bernardino National Forest. The Rim (as it is locally known) extends from Crestline to Big Bear, a distance of some 30 miles (48 km). Running Springs is served by Rim of the World High School and Mary Putnam Henck Intermediate School situated in Lake Arrowhead.

Logging in the San Bernardino Mountains was once done on a large scale, with the Brookings Lumber Company operation the largest. It operated on 8,000 acres (32 km2) between Fredalba and Hunsaker Flats (present-day Running Springs), and extending northward to Heap's Ranch and Lightningdale (near Green Valley Lake) between 1899 and 1912. It built a logging railroad to bring logs to the mill at Fredalba. The Shay locomotives had to be disassembled and hauled by wagon up the mountain, since the railroad operated in the high country but did not connect to other railroads in the lowlands. About 60% of the finished lumber was hauled by wagon down the steep grades to the Molino box factory in Highland, which made packing crates for the citrus grown in the area. The remaining 40% went to the company's retail lumber yard in San Bernardino. In 1912, the company dismantled the Fredalba sawmill and moved much of the machinery to Brookings, Oregon.[15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23]

Education

[edit]It is in the Rim of the World Unified School District.[24]

In popular culture

[edit]Film producer David O. Selznick lived in Running Springs and decided to use neighboring Big Bear Lake for scenes in his 1939 film Gone With the Wind.[25] Movies filmed in Running Springs include Next (2007), When a Stranger Calls (2006), Communion (1989),[26] Small Town Saturday Night (2010), I'm Reed Fish (2006), Messenger of Death (1988), Demon Legacy (2014), The Bigfoot Project (2017) and Cold Cabin (2010).[27]

The film Running Springs was set and filmed in the Running Springs area.[28]

Sister cities

[edit] Sehmatal, Germany [citation needed]

Sehmatal, Germany [citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "2010 Census U.S. Gazetteer Files – Places – California". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "Children's Forest Visitor Center opens for season". Big Bear Grizzly. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ Kath, Laura and Pamela Price (2011). Fun with the Family Southern California: Hundreds of Ideas for Day Trips with the Kids. Rowman & Littlefield. Page 133. ISBN 9780762774753.

- ^ Weeks, John Howard (2008). Inland Empire. Arcadia Publishing. Page 83. ISBN 9780738559070.

- ^ Burwell, Maria Teresa (2007). Fodor's 2008 Los Angeles: Plus Disneyland & Orange County. Fodor's Travel Publications. Page 250. ISBN 9781400018062.

- ^ Bellamy, Stanley E. (2007). Running Springs. Arcadia Publishing. Page 10. ISBN 9780738546797.

- ^ "The history of Running Springs". The Rim of the World Historical Society. Archived from the original on December 26, 2009. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "U.S. Census website".

- ^ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - Running Springs CDP". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ "Census.gov". Census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Cite web |url= https://gis.data.ca.gov/maps/CDEGIS::legislative-districts-in-california-2/about |title=Statewide Database |publisher=GregnCA |access-date=May 16, 2024

- ^ "California's 23rd Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- ^ Barnhill, John, "Logging No Easy Task," Trainboard Web site (http://www.nps.gov/gosp/photosmultimedia/photogallery.htm) Retrieved 6-19-11.

- ^ "Forests of Inland Southern California," San Bernardino County Museum Web site ("Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 26, 2011. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)) Retrieved 6-19-11 - ^ "Lima Machine Works," photo of Brookings Lumber Co. locomotive (http://www.shaylocomotives.com/data/lima/sn-154.htm) Retrieved 6-19-11.

- ^ "Logging the San Bernardino Mountains," Big Bear History Web site ("Big Bear History". Archived from the original on March 25, 2012. Retrieved August 20, 2014.) Retrieved 6-19-11.

- ^ Garrett, Lewis, Place Names of the San Bernardino Mountains, pp. 37, 47, 77-78, Big Bear Valley Historical Society, Big Bear City, CA, 1998.

- ^ Robinson, John W., The San Bernardinos: The Mountain Country from Cajon Pass to Oak Glen: Two Centuries of Changing Use, pp. 25-47, Big Santa Anita Historical Society, Arcadia, CA, 1989.

- ^ Core, Tom, Big Bear: The First 100 Years, pp. 306-8, The Core Trust, Big Bear City, CA, 2002.

- ^ Belden, L. Burr, "Brookings Turns Lumbering Into Big Business," San Bernardino Sun-Telegram, San Bernardino, CA, Nov. 29, 1953.

- ^ La Fuze, Pauliena B., Saga of the San Bernardinos, Hogar Pub. Co., 1984.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: San Bernardino County, CA" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. p. 8 (PDF p. 9/12). Retrieved October 4, 2024. - Text list

- ^ Bellamy, Stanley E. and Russel L. Keller (2006). Big Bear. Arcadia Publishing. Page 119. ISBN 9780738531113.

- ^ Cozad, W. Lee (2006). More Magnificent Mountain Movies. Page 299. ISBN 9780972337236.

- ^ "Filming Location Matching "Running Springs, California, USA" (Sorted by Popularity Ascending)". IMDb.

- ^ "Running Springs". Retrieved August 3, 2020 – via www.imdb.com.