Run, Nigger, Run

"Run, Nigger, Run" (Roud 3660) is a folk song first documented in 1851. It is known from numerous versions. Responding to the rise of slave patrols in the slave-owning southern United States, the song is about an unnamed black man who attempts to run from a slave patrol and avoid capture. The song was released as a commercial recording several times, beginning in the 1920s, and it was included in the 2013 film 12 Years a Slave.

History and documentation

In the mid-nineteenth century, black slaves were not allowed off their masters' plantations without a pass, for fear that they would rise against their white owners; such uprisings had occurred before, such as the one led by Nat Turner in 1831. However, it remained common for slaves to slip away from the plantations to visit friends elsewhere. If caught, running from the slave patrols was considered better than attempting to explain oneself and facing the whip. This social phenomenon led the slaves to create a variety of songs regarding the patrols and slaves' attempts to escape them.[1] One such song is "Run, Nigger, Run", which was sung on plantations in much of the Southern United States.[2]

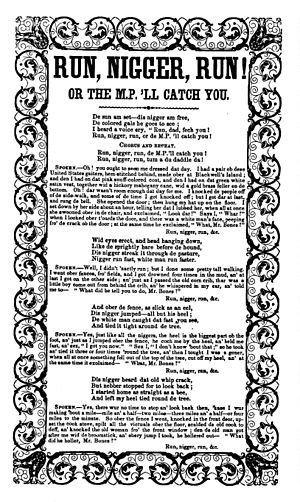

It is not certain when the song originated, although John A. Wyeth describes it as one of the oldest of the plantation songs, songs sung by slaves working on Southern plantations.[2] Larry Birnbaum notes lyrical parallels in some versions to earlier songs, such as "Whar You Cum From", first published by J. B. Harper in 1846.[3] According to Newman Ivey White, the earliest written documentation of "Run, Nigger, Run" dates to 1851, when a version was included in blackface minstrel Charlie White's White's Serenaders' Song Book.[1]

After the American Civil War, the song was documented more extensively. Joel Chandler Harris included a version of it in his Uncle Remus and His Friends (1892), and in 1915, E. C. Perrow included a version with his article "Songs and Rhymes from the South" in The Journal of American Folklore. Dorothy Scarborough and Ola Lee Gulledge, in their book On the Trail of Negro Folk-songs, included two versions, collected from two different states, and in his book American Negro Folk-Songs (1928), Newman Ivey White includes four different variations.[4] Folklorist Alan Lomax recorded folk versions from at least two different sources, one in 1933 from a black prisoner named Moses Platt, and another in 1937 from a white fiddler named W. H. Stepp.[3]

Commercial recordings of the song began in the 1920s, many by white singers. In 1924, Fiddlin' John Carson recorded his version of the song. By the end of the decade at least another three recordings had been produced, by Uncle Dave Macon (1925), Gid Tanner and the Skillet Lickers (1927), and Dr. Humphrey Bate and His Possum Hunters (1928).[3]

In 2013 the song was used in 12 Years a Slave, Steve McQueen's film adaptation of the memoir by Solomon Northup. In the film, a white carpenter named John Tibeats (portrayed by Paul Dano) leads a group of slaves in a rendition of the song. Hermione Hoby of The Guardian described the scene as "nauseating",[5] and Dana Stevens of Slate found it to be "hideous".[6] Kristian Lin of the Fort Worth Weekly wrote that, though the song had initially been used by black slaves to encourage escapees and warn them of the dangers involved, when performed by the character of Tibeats it became a taunt, "like a prison guard who jingles the keys for the prisoners to hear, reminding them of what they don't have".[7]

Contents and versions

Various versions of the song exist, though all focus on a (usually unnamed) black person running away from, or to avoid, slave patrols (referred to as a "patter-rollers" or "patty-rollers" in the song).[8] The White's Serenaders' Song Book version is presented as a narrative, with both sung and spoken parts. In this version, the evader is caught temporarily, but escapes at great speed after he "left my heel tied round de tree".[9]

Scarborough and Gulledge record a later version as follows:

Run, nigger, run; de patter-roller catch you

Run, nigger, run, it's almost day

Run, nigger, run, de patter-roller catch you

Run, nigger, run, and try to get away

Dis nigger run, he run his best

Stuck his head in a hornet's nest

Jumped de fence and run fru the paster

White man run, but nigger run faster[10]

Some versions of this song include events which occur to the slave during his escape. A version recorded in Louisiana, for instance, has the escapee losing his Sunday shoe while running, while another version has the black man lose his wedding shoe. In other versions, the runner is described as tearing his shirt in half. Still others have the runner point out another slave, one who is hiding behind a tree, in an effort to distract his pursuer.[11] E. C. Perrow records the following verses, found in Virginia:

Es I was runnin' through de fiel',

A black snake caught me by de heel.

Run, nigger, run, de paterrol ketch yuh!

Run, nigger, run! It's almos' day!

Run, nigger, run! I run my bes'

Run my head in a hornet's nes'.

Run, nigger, run![12]

Themes

White finds parallels between "Run, Nigger, Run" and African-American spiritual songs, in which themes of a hunted person running, seeking a place of safety and asylum, were common. These themes, he writes, may be derived from the sermons of slavemasters and campfire songs sung by groups of slaves. White records one song from North Carolina with the refrain "Run, sinner, run, an' hunt you a hidin' place", repeated as in "Run, Nigger, Run".[13] He likewise finds a "psychological connection" between this song and a spiritual often called "City of Refuge", which features the refrain

They had to run, they had to run

They had to run to the City of Refuge

They had to run.[1]

The act of running itself is a common theme in slave literature and folklore, taking both literal and metaphorical forms. The ability for blacks to run faster than whites was considered of such importance that a common proverb of the time went "What you don' hab in yo' haid, yuh got ter' hab in yo' feet".[14] Slave folksongs praised blacks for their running capabilities, comparing them to "a greasy streak o' lightning" or stating that one "ought to see that preacher [nigger, man] run".[15] The black runner's ability to escape white pursuers is rarely in doubt, and consequentially the escape is ultimately successful. These conventions carried over, through the slave narrative genre, into written African-American literature.[14]

See also

References

- ^ a b c White 1928, p. 168.

- ^ a b Scarborough & Gulledge 1925, p. 23.

- ^ a b c Birnbaum 2013, p. 84.

- ^ White 1928, pp. 168–69.

- ^ Hoby 2014, Paul Dano.

- ^ Stevens 2014, Entry 13.

- ^ Lin 2013, Further Thoughts.

- ^ Scarborough & Gulledge 1925, p. 24.

- ^ LOC, Run, nigger, run!.

- ^ Scarborough & Gulledge 1925, p. 25.

- ^ Scarborough & Gulledge 1925, p. 24–25.

- ^ Perrow 1915, p. 138.

- ^ White 1928, p. 78.

- ^ a b Dance 1987, p. 4.

- ^ Dance 1987, p. 3.

Works cited

- Birnbaum, Larry (2013). Before Elvis: The Prehistory of Rock 'n' Roll. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-8638-4.

- Dance, Daryl Cumber (1987). Long Gone: The Mecklenburg Six and the Theme of Escape in Black Folklore. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-0-87049-512-0.

- Hoby, Hermione (4 January 2014). "Paul Dano: there's light at the end of his journeys into darkness". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- Lin, Kristian (31 October 2013). "Further Thoughts on '12 Years a Slave'". Fort Worth Weekly. Archived from the original on 22 December 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- Perrow, E.C. (1915). "Songs and Rhymes from the South". The Journal of American Folklore. 28 (108): 129–90. doi:10.2307/534506. JSTOR 534506.

- Run, nigger, run! or the M. P. 'll catch you. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 9 January 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- Scarborough, Dorothy; Gulledge, Ola Lee (1925). On the Trail of Negro Folk-songs. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. OCLC 1022728.

- Stevens, Dana (17 January 2014). "Entry 13: My problem with 12 Years a Slave". Slate. Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- White, Newman Ivey (1928). American Negro Folk-Songs. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674012592. OCLC 411447.