Romualdo de Toledo y Robles

Romualdo de Toledo y Robles | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Tiburcio Toledo Robles 1895 Molina de Aragón, Spain |

| Died | 1974 Madrid, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | civil servant |

| Known for | politician, education official |

| Political party | Patriotic Union (Spain), Carlism, FET y de las JONS |

Tiburcio Romualdo de Toledo y Robles (1895–1974) was a Spanish politician, civil servant and education theorist. He is known mostly as the high official of Ministerio de Educación Nacional and head of the primary education system in 1937–1951. His political allegiances changed; in the 1920s member of the primoderiverista Unión Patriótica, in the 1930s he was an active Carlist but then got fully aligned with the Franco regime. In 1933–1936 he was deputy to the republican Cortes, and in 1943–1958 he served in the Francoist parliament, Cortes Españolas. Between 1937 and 1958 he was member of the Falange Española Tradicionalista executive, Consejo Nacional. In 1925–1930 de Toledo served as councilor in the Madrid ayuntamiento, since 1929 as teniente de alcalde; in the town hall he was largely responsible for education-related issues. Since 1939 until death he was in executive board of the news agency EFE.

Family and youth

[edit]

The surname of Toledo/de Toledo is among the most popular in Spain; it was recorded already in the early medieval era. However, it is not clear what branch Romualdo descended from and there is close to nothing known about his ancestors. His father, Eduardo Toledo, held a small estate in Molina de Aragón, in the province of Guadalajara. None of the sources consulted provides information when he married Josefa Robles Arnal, a girl from the same town. The couple settled at the Eduardo's possessions. It is not clear how many children they had, yet apart from Romualdo they had at least one more son, Pascual[1] (who unlike his brother would not use the ennobled version of their surname and would appear and “Pascual Toledo Robles”) and at least one daughter, Maria de los Dolores.[2] Both Eduardo and Josefa perished during the deadly influenza epidemic, known as Spanish flu, in 1914.[3] On behalf of the children, the estate was administered by their uncle Pascual.

At the age of 11 Romualdo – at the time known rather by his first name Tiburcio – left the family home and in 1906 he became a boarder in Instituto General y Técnico in Guadalajara.[4] During the following years of 1907[5] and 1908[6] he excelled as a student; in 1909 he opted for bachillerato in algebra and trigonometry,[7] the title which he obtained in 1911.[8] In 1912[9] he moved to Zaragoza to commence university studies at Facultad de Ciencias, the faculty dedicated mostly to physics and chemistry.[10] He completed the curriculum and in 1916[11] he graduated as doctor de ciencias exactas.[12] Subject to military service, he formed part of “reemplazo de 1916” – though unclear whether he actually served – and in 1920 passed to reserve in Tropas de Sanidad Militar.[13] In the early 1920s he moved to Madrid and was employed as auxiliar de meteorología in Observatorio de Madrid; first noted at this post in 1922,[14] he would hold the job for some 10 years to come.

Prior to 1926[15] de Toledo married Remigia del Castillo Asensio (1895–1935); little is known about her except that she was related to Teruel.[16] The couple had 4 children,[17] born between the mid-1920s and the mid-1930s.[18] Remigia died prematurely in February 1935;[19] in October 1935 the widower remarried with Pilar Sanz Beneded (died 1992).[20] His second wife descended from a well-established Zaragoza family;[21] her father was an entrepreneur[22] and the retail business he started was later developed into a large-scale enterprise.[23] In the marriage with Pilar de Toledo had further 3 children.[24] None of his descendants would become a widely known personality, yet Romualdo de Toledo Sanz gained some recognition as in the 1970s and the 1980s he ascended to high management positions in the publishing house Grupo 16.[25] Among more distant relatives his maternal cousin José María Araúz de Robles was a politician an bull-breeder,[26] while his nephew-in-law Angel Sanz Briz became known for saving Hungarian Jews in 1944–1945.[27]

Dictadura: councilor and education official (1925–1930)

[edit]Political preferences of de Toledo's ancestors are unknown; there is neither any data available on his public activities in the academic period. First information on his political endeavors is related to the mid-1920s;[28] during the early period of Primo de Rivera dictatorship he joined the Madrid structures of the newly created state party, Unión Patriotica. He was an active member, and in 1925 as one of 10 vocales he entered Junta Provincial of the organisation.[29] The same year de Toledo as one of 64 alternate councilors entered the Madrid town hall,[30] in the dictatorship era not elected but appointed by the civil governor. In 1927 he became the interim councilor in the ayuntamiento[31] and assumed some administrative duties, e.g. in 1928 dealing with local calamities.[32] In 1929 the council elected him as one of 10 deputy mayors;[33] de Toledo was responsible for the Universidad district.[34] He was noted as active on numerous fields, from public transport[35] to quality of bread[36] to organizing fiestas veraniegas.[37]

Parallel to his duties in the Madrid town hall, de Toledo commenced career in central administration. In 1926 he was nominated secretario auxiliar in Ministerio de Instrucción Pública[38] and entered some internal committees within the ministry.[39] He retained this role during following years[40] and assumed positions in various dependent bodies, like Consejo Superior del Patronato de la Federación de Mutualidades Escolares.[41] He was noted conferencing on “problema escolar”,[42] writing articles,[43] and discussing issues like financing teachers by large municipalities[44] or city councils co-financing certain types of schools.[45] In the late 1920s his activities in local administration and education converged, as he became delegado de enseñanza in the ayuntamiento,[46] referred to as “paladín de la instrucción pública en nuestro activo Municipio”.[47]

In the late 1920s de Toledo was gradually gaining some prestige. In 1928 he was nominated to Gran Cruz del Mérito Civil.[48] He was celebrated especially in his native Molina,[49] where in 1928 he entered the commisión which first prepared the visit of Alfonso XIII[50] and then greeted the king during his brief visit to the town.[51] He also lobbied for construction of Calatayud – Molina – Cuenca railway line,[52] the project which has never materialized, and remained engaged in some works on regulation of the water regime, carried out by Ministerio de Fomento.[53] He also kept climbing the party ladder, and in 1930 became Unión Patriotica delegate for the Guadalajara province.[54] Throughout the late 1920s he remained employed by the Madrid Observatorio[55] and even obtained the prize, awarded to meritorious auxiliares de Meteorología.[56] At the time the press started to refer to him as Romualdo rather than Tiburcio. Also, though in official documents he was noted as “Tiburcio Romualdo Toledo Robles”, increasingly frequently in newspapers he was listed as “de Toledo y Robles”.[57]

Republic: SADEL director and Cortes deputy (1930–1936)

[edit]

In 1930 de Toledo lost his seat in the ayuntamiento.[58] In 1931 he was running from the Congreso district[59] as a candidate of Unión Monárquica Nacional,[60] yet failed. Since then he focused on activity in numerous Catholic organizations, noted in Acción Católica,[61] Confederación Nacional de Familiares y Amigos de los Religiosos,[62] and Asociación Católica de Padres de Familia.[63] His activity was mostly about the education system, be it lectures[64] or articles.[65] In 1933 de Toledo co-founded SADEL, Sociedad Anonima de Ensañanza Libre; formally a commercial company, its objective was to confront secular legislation and provide institutional framework for Catholic schools.[66] Initially he entered the executive,[67] yet he shortly rose to CEO. SADEL proved a success; in the mid-1930s there were 16,318 students registered in its network.[68]

Already during his service in the ayuntamiento de Toledo approached the Traditionalists,[69] and these bonds strengthened. In early 1933 he was for the first time mentioned by the Carlist mouthpiece, El Siglo Futuro,[70] later to appear frequently on its pages as an education pundit.[71] He started to speak on schooling system during Carlist rallies, e.g. in Segovia[72] or in Valencia.[73] There is no confirmation that he formally joined Comunión Tradicionalista, though the party fielded him as candidate in the 1933 elections.[74] Running in the district of Madrid province he appeared as “agricultor” within the broad right-wing alliance.[75] With 71,463 votes de Toledo emerged triumphant;[76] in the chamber he joined the Carlist minority and became its secretary.[77] Among cohorts of lawyers, academics and journalists, he was one of only two MPs “licenciados in ciencias”.[78]

De Toledo was an active parliamentarian;[79] most of his activity revolved around education. First steps were aimed at derogating secular legislation;[80] later he worked on new laws, be it in comisión de instrucción pública,[81] comisión de presupuestos,[82] plenary sessions[83] or co-signing proposals of new laws.[84] In 1935 he demanded investigation as to teachers involved in the Asturias revolution.[85] However, he voiced also in issues like agriculture[86] and lobbied for investments in Molina, be it roads[87] or telephones.[88] He kept conferencing,[89] giving lectures at various opportunities across Spain;[90] in Covadonga he co-launched a project dubbed "Reconquista de Enseñanza".[91] At the time he no longer worked in meteo services.[92]

Active within Traditionalist structures, he kept opening new círculos[93] and took part in propaganda tours,[94] be it in Aragón[95] or Cantabria.[96] Politically he joined the Carlist faction which supported a monarchist alliance with the Alfonsists,[97] and engaged in what emerged as the National Bloc.[98] In the 1936 elections he was supposed to run on a joint Candidatura Contrarrevolucionaria ticket from Logroño[99] and was allegedly confirmed by Gil-Robles,[100] but following internal squabbles within the local Riojan alliance[101] he was eventually left out and decided to run on his own.[102] During the campaign he declared that the republic was “irreformable” and had no future.[103] As elections turned out to be chiefly a confrontation between Frente Popular and CEDA-led alliances, all independent candidates were trashed; with merely 9,442 votes gathered de Toledo failed.[104]

Early war: in hiding and in officialdom (1936–1937)

[edit]

No source provides information whether de Toledo was engaged in anti-Republican Carlist conspiracy or whether he was even aware of it. In the early summer he remained in Madrid, and on July 14 he attended the funeral of Calvo Sotelo.[105] However, 4 days later, at the moment of the July 1936 coup, de Toledo was already on vacation in the small Gipuzkoan spa of Cestona,[106] where he holidayed together with another Traditionalist politician, Joaquín Beunza. The latter was soon detained by the Anarchist militia, and de Toledo was warned that he might soon follow suit. According to his own account there was a civil governor who bothered to Cestona to get him arrested, yet at the time he was already fleeing in a train westwards. He settled in Santander, unclear whether under false identity or incognito and whether single or accompanied by the family. De Toledo spent 5 months in the Cantabrian capital.[107] It is neither known how he made it to the Nationalist zone; in June 1937, shortly after the fall of Biscay, he appeared in San Sebastián, allegedly “tras grandes peligros y persecuciones”.[108] As he was believed to had fallen victim of Republican repression, his re-appearance was sort of a media scoop. Numerous newspapers issued in the Nationalist zone published his description of Republican-held Santander, though all accounts were singularly uninformative as to details of his personal lot.[109]

One scholar claims that when back in October 1936 Franco formed his quasi-government, Junta Técnica del Estado, de Toledo was along Joaquín Bau one of the “two of the more ‘collaborationist’ Carlists” who headed its departments, namely this of education.[110] Also some other historians confirm this claim,[111] but the source referred in these works does not.[112] The first sourced information on his entry into Junta Técnica is from late July 1937, around a month after his appearance in the Nationalist zone; he was nominated “consejero de la Comisión de Cultura”[113] in Comisión de Cultura y Ensañanza, sort of quasi-ministry of education, at the time headed by José María Pemán. Almost immediately de Toledo started publishing various articles on education, repeated in numerous press titles; the first one was printed in August 1937.[114] It is not clear whether he resumed activity within Carlism, especially that at the time Comunión Tradicionalista was formally amalgamated into Falange Española Tradicionalista. None of numerous works on wartime Carlism mentions him as taking part in party operations, and specifically whether he supported or opposed the unification.[115] In October 1937 Franco decided to appoint members of Consejo Nacional, the FET executive supposed to advise the caudillo. In the nomination decree among 50 appointees de Toledo was listed on position 49.[116] He was among 11 Carlists nominated[117] (according to other source among 12 Carlists).[118]

Early Francoism: Head of Primary Education (1938–1951)

[edit]

In February 1938 de Toledo was nominated "subsecretario de primera enseñanza"[119] within the ministry of education, headed by Pedro Sainz Rodríguez in the first regular Nationalist government. In March his position was renamed to "Jefe del Servicio Nacional de Primera Enseñanza".[120] His immediate tasks were purging and re-constructing the teacher corps, forming the new curriculum, and work on the future primary education law. According to some scholars, with Sainz and José Ibañez Martín he was among 3 key people in the ministry.[121] At the same time he became also "asesor in cuestiones educativas" within Auxilio Social.[122] Also in 1938 he formed part of a commission, tasked with "demonstrar la illegalidad de los poderes actuantes en la República en 18 julio de 1936".[123] Moreover, de Toledo was among “consejeros fundadores” of the semi-official news agency EFE,[124] and in January 1939 he was noted as consejero de la agencia.[125]

In August 1939 Saenz Rodríguez had to go; the ministry of education was taken over[126] by Ibáñez Martín. De Toledo was confirmed at his post, and together with Pemán (higher education) he headed two most important departments of the ministry.[127] His official title changed from "Jefe del Servicio" to "Directór General de Primera Enseñanza".[128] In September de Toledo was nominated to II. Consejo Nacional of FET, though the decree, which listed appointees according to what appeared as prestige, named him on position 77 out of 90 and among 13 Carlists in the body.[129] In the early 1940s Don Javier viewed these who joined Francoist structures without formal approval as half-traitors, yet de Toledo was not listed among these (like Rodezno or Bilbao) whose re-admission to Comunión Tradicionalista was out-of-the-question.[130] However, none of the sources consulted provides information that apart from personal relations he maintained any links to organized Carlist structures.[131]

In 1942 de Toledo was confirmed as member of the Francoist elite when re-appointed on position 46[132] to III Consejo Nacional.[133] When during first major redressing the system a quasi-parliament Cortes Españolas was set up, in 1943 by virtue of membership in Consejo de Toledo automatically became its member.[134] This sequence of appointments continued; in 1946 he was nominated to IV. Consejo Nacional (position 22)[135] which triggered nomination to the II. Cortes,[136] while the 1949 nomination (position 21)[137] guaranteed his seat in the III. Cortes.[138] Throughout all these years he remained Director General de Primera Enseñanza and one of the most influential people shaping the education system. His term came to the end after 12 years, when in 1951 Ibáñez Martín ceased as minister of education and was replaced by Joaquín Ruiz-Giménez Cortés. It is not clear whether de Toledo was forced to resign or whether he decided to go himself; following a solemn farewell ceremony, he left the ministry in July 1951.[139]

Mid- and late Francoism: half-retiree and retiree (1952–1974)

[edit]

De Toledo's departure from the Ministry did not mean falling from grace. In 1952 he was nominated to VI. Consejo Nacional (for the first time the appointees were listed in alphabetical order),[140] which translated to membership in the IV. Cortes,[141] where he assumed presidency of commission working on the Spanish Guinea budget.[142] In 1954 he was received by Franco.[143] The year of 1955 brought nomination to VII. Consejo[144] and V. Cortes.[145] These bodies held little decision-making power, yet in the mid-1950s he was active in budgetary debates, e.g. in 1955 about housing[146] and in 1956 about real estate rental.[147] Historians note him particularly for the 1957 budgetary debate, when de Toledo was among chief opponents of the fiscal reform planned. He tried to block it with hundreds of amendments,[148] launched a counter-proposal of prolonging the existing budget,[149] claimed to defend “soberanía de las Cortes” and lambasted “persecución contra la gran propiedad”.[150] At the time he owned 80 ha in Motilla del Palancar, but it is not clear whether this conditioned his Cortes stand.[151]

Since 1937 de Toledo was not active in Carlist structures, though he cultivated personal relations with the collaborationist faction which sought rapprochement with the Alfonsists, led by conde Rodezno;[152] the latter once noted “Romualdo, tan identificado conmigo”.[153] De Toledo maintained these links also after death of Rodezno, e.g. when meeting Bilbao in 1955.[154] In early 1957 de Toledo was for the first time listed as one of “personalidades del Tradicionalismo” who took part in the Martires de la Tradición celebrations,[155] noted in this role also afterwards.[156] Later the same year he joined a large group of Traditionalist politicians who openly rebelled against dynastic leadership of the claimant Don Javier. He appeared in Estoril and declared Don Juan the legitimate Carlist heir,[157] yet there was no follow up on his part. It is not clear whether the episode contributed to him not being appointed in 1958 to the VIII. Consejo Nacional, which translated to expiration of his Cortes ticket;[158] thus, his 21-year term in Consejo and 15-year term in the parliament came to the end.

After 1958 de Toledo held no political role, though he continued as member of the EFE managing board,[159] in the mid-1960s hailed as “consejero más antiguo”.[160] There were some schools named after him,[161] few streets[162] and a “Premio José Ibañez Martin y Romualdo de Toledo y Robles”, awarded to the best Grupo Escolar.[163] He kept cultivating personal links with heavyweight collaborationist Carlists, who appeared at weddings of his children, e.g. Iturmendi, Oriol (Antonio) or Bau in 1967.[164] His last political engagement took place in 1969, when prince Carlos Hugo, son to the Carlist king-claimant, was expulsed from Spain. As a propagandistic measure, intended to demonstrate that Traditionalists kept supporting the regime, a group of “prohombres de la Comunión Tradicionalista” was assembled to offer “fervorosa adhesion” to the dictator; the event received massive press coverage. Together with Zamanillo, Oriol (JL), Oreja (R), Carcér and Ramírez Sinues, there was also de Toledo present.[165]

In historiography

[edit]

In historiography de Toledo appears mostly as one of key individuals responsible for development of the Francoist primary school system and one of 3-5 most important people in the Ministry of Education during early stages of the regime.[166] He is usually mentioned as the one who did his best to dismantle the Republican system, including purges among teachers.[167] Some authors claim he worked in line with Sainz Rodriguez and advanced the same model based on “national and Catholic ideals of the movement”,[168] others suggest he went further than Sainz when undoing the Republican legislation,[169] namely attempting to remove all traits of Rousseaism.[170] Scholars claim that his key objective was to build education system based on Catholic teaching,[171] going back to the model of St. Benedict[172] though saturating it with the Hispanic tradition.[173] To some he tried to ensure “ideological dominance of Catholicism rather than Fascism in all Spanish education”,[174] yet he might appear also in an opposite role, as “el artífice de la bases de la educación franquista, de clara inspiración fascista”.[175] Single authors prefer rather to mention Traditionalism as his point of reference[176] and one sees him as “encargado de llevar el nuevo espíritu totalitario y católico a las escuelas”.[177] He is usually criticized for implementing what is presented as outdated system, built on discipline and hierarchy[178] and stained by adherence to traditional social roles, nationalism and imperialism.[179]

Apart from educational practice, de Toledo is mentioned as one of major architects of Ley de Primera Ensañanza, adopted in 1945. Until then he regulated primary schooling mostly by means of ministerial circulars,[181] though work on the law commenced in already 1938 and Ley Orgánica of 1942 – unclear to what extent drafted by de Toledo - specified some organization foundations of the system.[182] He headed one of two competitive commissions, preparing their own drafts; (the other one was led by Sainz Rodríguez).[183] They were different both in terms of general spirit and structural design of the schooling system. Eventually the law “adopta un criterio ecléctico”[184] and with some modifications of 1965 and 1967 it remained in force until so-called “Ley Villar” was adopted in 1970.[185] One of its characteristic features was sex segregation, which prevailed until the late 1960s.[186] The popular present-day opinion is that the law institutionalized “retroceso importante” in the Spanish education.[187] In terms of numbers, during de Toledo's tenure the illiteracy rate dropped from 23% in 1940 to 17% in 1950,[188] while the gross enrolment ratio in primary education rose from 53% in the schooling year of 1940/41[189] to 69% in 1951.[190] This was possible, among others, by buildup of de Toledo-designed Servicio Español de Magisterio, the corporative system of educating primary-school teachers,[191] with 23,000 – mostly females – enrolled in the cursillos already in 1939.[192] Historians note that its characteristic feature was focus on rural counties, yet they claim that separate paths for teachers in urban and rural areas might have been counter-productive when it comes to erasing educational inequality across Spain.[193]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ La Unión 14.08.14, available here. Pascual was present as weddings of some of Romualdo’s children, e.g. Josefina, Hoja Oficial de Lunes 23.11.53, available here. He was representing Molina in Cámara de Propiedad Rústica in 1929, La Palanca 11.12.29, available here

- ^ she is listed as the sister when attending the second wedding of Romualdo, La Nacion 16.10.35, available here. She married a local lawyer, later to become a judge, Santiago Vigil de Quiñones, Nueva Alcarria 16.06.45, available here

- ^ unclear in what sequence. Upon her passing away the local newspaper did not mention Eduardo, La Unión 14.08.14, available here

- ^ La Region 02.10.06, available here

- ^ La Torre de Aragon 20.06.07, available here

- ^ La Union 06.06.08, available here

- ^ Flores y abejas 03.10.09, available here

- ^ Flores y abejas 25.06.11, available here

- ^ Toledo Robles, Tiburcio Romualdo entry, [in:] PARES website of Archivo Historico Nacional, available here

- ^ Jose Luis Cebollada Gracia, La seccion de quimicas de Zaragoza en las primeras decadas del siglo, [in:] Luis Español González (ed.), Estudios sobre Julio Rey Pastor: (1888–1962), Zaragoza 1990, ISBN 8487252648, pp. 327-339

- ^ Toledo Robles, Tiburcio Romualdo entry, [in:] PARES website of Archivo Historico Nacional, available here

- ^ ABC 25.05.74, available here. In Spanish academia of the time, this "ciencias exactas" stood mostly for mathematics, physics and chemistry

- ^ Boletin Oficial de la Provincia de Guadalajara 18.06.20, available here

- ^ Guía Oficial de España 1922, available here

- ^ in 1926 “distinguida esposa de nuestro buen amigo D. Romualdo de Toledo” is noted as giving birth to a child, to be named Eduardo, La Nacion 12.08.26, available here. In her later obituary notes when listing children Eduardo is listed after Josefina, which suggests that he had an older sister, born no later than in 1925

- ^ the daughter of Cipriano and Juana, related to Teruel, Teruel 17.12.28, available here

- ^ Josefina in 1953 married Carlos Maldonado, Hoja Oficial de Lunes 23.11.53, available here (it is not clear why she is listed as “Josefina de Toledo y Sanz”; back in 1945 when noted as cursillista, she was referred to as “Josefina de Toledo y del Castillo”, Anuario del Maestro 01.01.47, available here), Eduardo married María del Carmen Martínez de Galinsoga; he also appears as “Eduardo de Toledo y Sanz”, El Diario Palentino 08.10.50, available here, María del Carmen in 1950 married Pedro Areitío y Rodrigo, Hoja Oficial de Lunes 09.10.50, available here, María Dolores married Luis Serrano de Pablo

- ^ Josefina, Eduardo, Carmen and Dolores are listed as children of Romualdo and Remigia in La Epoca 11.02.35, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 11.02.35, available here. It is not clear whether her premature death was related to car accident, suffered in 1931, El Debate 07.06.31, available here

- ^ ABC 10.12.92, available here l

- ^ for “distinguida familia aragonesa” see Ahora 17.10.35, available here

- ^ her father was Felipe Sanz Espuis, her brother was Felipe San Beneded, the one who developed the business, see Mariano García, El Bazar X, el gran teatro de los sueños de los zaragozanos durante 70 años, [in:] Heraldo 08.04.24, available here

- ^ developed later by his son, and romualdo’s brother in-law Felipe Sanz Beneded, see El Bazar X de Zaragoza, [in:] ZaraGozala service 03.09.24, available here. For Felipe San Beneded as brothers-in-law to Romualdo see Hoja Oficial de Lunes 18.05.53, available here

- ^ Pilar in 1959 married Juan Miguel Antoñanzas, Romualdo (born 1938) in 1967 married Esperanza González Green, and Blanca married Ricardo de Juanes y Lagonot, Romualdo de Toledo y Robles entry, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ Diario de Burgos 13.03.86, available here, El adelantado 22.09.87, available here. He was later imprisoned and trialed with fraud charges advanced, José Díaz Herrera, Pedro J. Ramírez, al desnudo, Madrid 2009, ISBN 9788496797338, pp. 28-29

- ^ de Toledo and Arauz de Robles were cousins since their mothers, respectively Josefa Robles Arnal and Maria Robles Arnal, were sisters (children of Vicente Robles and Dolores Arnal)

- ^ he was son of Felipe San Beneded, the brother of de Toledo's second wife, see Angel Maximo Sanz Briz entry, [in:] Geni service, available here

- ^ one historian counts de Toledo among Carlists “claramente vinculados al sistema de la restauracion liberal y alfonsina”, Manuel Martorell Pérez, Nuevas aportaciones históricas sobre la evolución ideológica del carlismo, [in:] Gerónimo de Uztariz 16 (2000), p. 104. It is not clear what is the basis of this claim, since de Toledo was not active in public before 1923, i.e. before the regime of liberal democracy was replaced with dictatorship

- ^ El Debate 12.12.25, available here

- ^ Diario de la Marina 07.11.25, available here

- ^ La Nacion 19.12.27, available here

- ^ La Nacion 24.09.28, available here

- ^ there were 51 votes cast in support, 3 votes blank and 0 votes against, El Debate 20.07.29, available here

- ^ Guía Oficial de España 1930, available here

- ^ e.g. in 1929 discussing taxi fares, La Nacion 11.07.29, available here

- ^ El Debate 01.11.29, available here

- ^ La Nacion 29.07.29, available here

- ^ La Nación 13.08.1926

- ^ La Voz de de Peñaranda 24.04.26, available here

- ^ La Nacion 11.07.29, available here, also La Nacion 17.10.27, available here

- ^ La Libertad 07.05.27, available here

- ^ La Nacion 03.08.29, available here

- ^ La Escuela Moderna 07.08.29, available here

- ^ El Liberal 03.10.29, available here

- ^ La Voz 08.10.29, available here

- ^ El dia grafico 22.05.30, available here

- ^ La Voz 08.10.29, available here

- ^ Unión Patriótica 15.11.28, available here. There there is no confirmation he received the honour, apart from the Gran Cruz awarded to him in 1945, Diario de Burgos 01.07.45, available here

- ^ La Palanca 18.05.27, available here

- ^ El Debate 06.06.28, available here

- ^ Renovacion 07.06.28, available here

- ^ Flores y abejas 18.11.28, available here

- ^ La Correspondencia Militar 09.08.28, available here

- ^ Union Patriotica 15.07.30, available here

- ^ for 1927 see Guía Oficial de España 1927, available here for 1929 see Guía Oficial de España 1929, available here

- ^ El Imparcial 08.09.26, available here

- ^ the first case identified is dated 1925, El Heraldo de Madrid 07.11.25, available here

- ^ in late 1930 he was already noted as ex-consejal, El Iris 29.09.30, available here

- ^ El Debate 10.03.31, available here

- ^ El Debate 06.10.30, available here

- ^ namely in its Asamblea Nacional, La Epoca 06.11.30, available here

- ^ where he served as treasurer, La Epoca 21.12.31, available here

- ^ where he gave a lecture “Estudio sobre la organización escolar en Madrid”, La Epoca 03.05.32, available here

- ^ e.g. during Semana de Estudios Pedagógicos, La Escuela Moderna 16.12.31, available here, or at the conference of Padres de Familia, El Siglo Futuro 07.02.33, available here

- ^ El Universo 17.02.33, available here

- ^ “destacó durante la guerra escolar como uno de los máximos dirigentes de la ofensiva católica contra las reformas republicanas”, Francisco Morente Valero, Política educativa y represión del Magisterio en la España franquista (1936–1943), [in:] Spagna contemporanea 16 (1999), p. 65

- ^ La Nacion 23.08.33, availale here

- ^ of which 58% paid and 42% were admitted according to various free schemes, Esto 25.04.35, available here

- ^ already in 1929 at the sitting of the Madrid city council he proposed that a plaza be named after Marqués de Cerralbo, a deceased Carlist political leader, El Debate 15.09.29, available here. Also in the town hall, in 1929 he co-organised some events fiestas jointly with a Carlist, Jaime Chicharro, La Nacion 29.07.29, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 10.01.33, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 13.05.33, available here

- ^ Ahora 14.03.33, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 18.03.33, available here

- ^ “candidatos afiliados a la Comunión Tradicionalista”, El Siglo Futuro 11.11.33, available here

- ^ in the press the alliance was named “candidatura agraria”, El Heraldo de Madrid 26.10.33, available here, “Coalición Antirevolucionaria”, Renovacion Española November 1933, available here, “candidatura antimarxista”, El Universo 03.11.33, available here, or “Unión de Derechas”, El Siglo Futuro 10.11.33, available here

- ^ see his 1933 ticket at the official Cortes service, available here All candidates on the list received a very similar number of votes, a mark of electors block-voting regardless of specific party afiliations of individuals on the list, see Luz 05.12.33, available here

- ^ La Nacion 16.12.33, available here

- ^ There were 177 lawyers, 32 engineers, 24 writers/journalists, 23 doctors, 15 landowners, 15 workers, 6 religious, 4 military and only 2 “licenciados en ciencias”, La Voz 20.12.33, available here

- ^ he was an important member of the Carlist parliamentary group; when the leader of the minority Rodezno fell sick, it was de Toledo who pronounced on behalf of the entire minority, Víctor Manuel Arbeloa Muru, De la Comisión Gestora a la Diputación Foral de Navarra, (1931–1935), [in:] Príncipe de Viana 260 (2014), p. 614

- ^ La Nacion 29.12.33, available here

- ^ Luz 07.01.34, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 20.06.34, available here. He demanded that the government stops crediting National Council of Culture as 37 of its 57 members were hostile left-wingers, Carolyn P. Boyd, Historia Patria. Politics, History, and National Identity in Spain, 1875–1975, Princeton 2020, ISBN 9780691222035, p. 199. In 1935 he also entered comisión investigadora in the Nombela affair, La Epoca 30.11.35, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 02.02.34, available here, or especially El Siglo Futuro 02.12.35, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 01.03.34, available here, La Nacion 16.11.34, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 29.01.35, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 12.05.34, available here

- ^ Labor 17.02.34, available here

- ^ El Sol 28.03.34, available here

- ^ and writing, see El Siglo Futuro 26.06.34, available here

- ^ for San Sebastian see El Siglo Futuro 24.08.34, available here

- ^ launched in Covadonga, it united various Catholic organisations; de Toledo was among its most outspoken leaders, El Siglo Futuro 10.07.34, available here

- ^ de Toledo was last mentioned among te observatorio staff in 1930, Guía Oficial de España 1930, available here. In 1935 he was released from Cuerpo Técnico de Auxiliares de Meteorología, Boletín oficial de la Dirección General de Aeronáutica July 1935, available here

- ^ e.g. in Murcia, see El Siglo Futuro 30.04.35, available here

- ^ in 1934 the claimant Alfonso Carlos nominated de Toledo “adjunto de la Delegación especial de Propaganda”, Melchor Ferrer, Historia del tradicionalismo español, vol. XXX/2, Sevilla 1979, p. 36

- ^ e.g. during the Carlist propagande week in September 1935 in Aragón he spoke on 21. in Jaca, on 22. in Sariñena and Fraga, and on 29. in Huesca, El Siglo Futuro 04.09.35, available here

- ^ for numerous locations listed see El Siglo Futuro 24.09.35, available here

- ^ e.g. in 1934 he took part in a banquet to honor Goicoechea, with other members of the faction Rodezno and Bilbao also present, La Nacion 21.04.34, available here

- ^ in National Bloc de Toledo was listed as one of Carlists who “play a significant part”, along Rodezno, Pradera, Bau, Lamamie, Palomino, Comin and Arellano, Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931–1939, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 9780521086349, pp. 190-191

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 20.01.36, available here. In early 1935 one newspaper referred to de Toledo as “profesor de la Universidad Central”, Ahora 28.01.36, available here, yet no other source confirms he was indeed member of the university staff

- ^ the year of 1934 produced a notorious Cortes exchange between de Toledo and Gil Robles; when listening to intervention of the latter, the former interrupted with “this is Traditionalism!”; Gil-Robles replied that Traditionalism is not exclusively owned by the Carlists, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 158

- ^ for the version that it was the local CEDA leader Tomás Ortiz de Solórzano who supported the offshot Carlist branch known as Cruzadistas and excluded de Toldeo from the list see El Siglo Futuro 07.02.36, available here. More details, which seem to confirm this version, in Francisco Bermejo Martín, La 2a República en Logroño. Elecciones y contexto politico, Vitoria 1984, ISBN 9788400059446, pp. 368-371

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 13.02.36, available here

- ^ Manuel Álvarez Tardío, Roberto Villa García, 1936. Fraude y violencia en las elecciones del Frente Popular, Barcelona 2017, ISBN 9788467049466, p. 223

- ^ in the Logroño electoral district the most-voted right-wing candidate got 45,761 votes, and the most-voted Popular Front candidate got 37,208 votes, Álvarez Tardío, Villa García 2017, p. 589

- ^ El Dia de Palencia 14.07.36, available here

- ^ according to his own account, referred after Pensamiento Alaves 01.07.37, available here

- ^ Pensamiento Alaves 01.07.37

- ^ La Rioja 25.06.37, available here

- ^ e.g. in November 1936 press in the rebel zone listed de Toledo among these, “por cuya suerte todos abrigamos temores”, Mirobriga 22.11.36, available here

- ^ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 272

- ^ Juan Carlos Peñas Bernaldo de Quirós, El Carlismo, la República y la Guerra Civil (1936–1937). De la conspiración a la unificación, Madrid 1996, ISBN 9788487863523, p. 224, also Hugh Thomas, The Spanish Civil War, London 2012, ISBN 9780141011615, p. 412

- ^ the authors point to Boletín Oficial del Estado of October 2, 1936 as their source; however, the issue in question does not contain any information on de Toledo’s nomination, compare BOE 02.10.36, available here. Until late 1936 it was Fidel Dávila who kept signing as Presidente de la Comisión de Cultura y Ensañanza, his last identified document is dated December 9, 1936, compare Boletin Oficial de la Provincia de Soria 15.12.36, available here. In December 1936 it was Pemán started to sign, initially with confused timing overlapping with Dávila’s documents, for December 7, 1936 see Boletin Oficial de la Provincia de Soria 15.12.36, available here

- ^ La Rioja 28.07.37, available here

- ^ El Luchador 28.08.37, available here

- ^ compare Blinkhorn 2008, Peñas Bernaldo 1996, also Aurora Villanueva Martínez, El carlismo navarro durante el primer franquismo, 1937–1951, Madrid 1998, ISBN 9788487863714; Ramón María Rodón Guinjoan, Invierno, primavera y otoño del carlismo (1939–1976) [PhD thesis Universitat Abat Oliba CEU], Barcelona 2015; Manuel Martorell Pérez, La continuidad ideológica del carlismo tras la Guerra Civil [PhD thesis in Historia Contemporanea, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia], Valencia 2009. The period is also covered in less detail in Francisco Javier Caspistegui Gorasurreta, El naufragio de las ortodoxias. El carlismo, 1962–1977, Pamplona 1997, ISBN 9788431315641, and Daniel Jesús García Riol, La resistencia tradicionalista a la renovación ideológica del carlismo (1965–1973) [PhD thesis UNED], Madrid 2015

- ^ El Adelanto 22.10.37, available here

- ^ Villanueva Martínez 1998, p. 53, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 361

- ^ Jordi Canal, El carlismo, Madrid 2000, ISBN 8420639478, p. 340

- ^ El Diario de Avila 03.02.38, available here

- ^ it was part of a unit named Inspección de Primera Enseñanza y Maestros Nacionales

- ^ along the minister Sainz Rodríguez and the head of CSIC Ibañez Martin, Jorge Caceres-Munoz, Tamar Groves, Mariano Gonzalez-Delgado, Progressive Education on the Eve ot the Civil War and the Question of Its Destruction by the Franco Regime, [in:] Raanan Rein, Susanne Zepp (eds.), Untold Stories of the Spanish Civil War, New York 2024, ISBN 9781032539300, p. 233

- ^ of FET, Falange 02.04.38, available here

- ^ composed of some 40 members, La Ultima Hora 22.12.38, available here

- ^ Hoja Oficial de Lunes 13.01.69, available here

- ^ Diario de Burgos 18.01.39, available here

- ^ following a brief interim rule in the ministry by de Toledo’s fellow Carlist code Rodezno; for their ideological proximity compare “Romualdo, tan identificado conmigo”, Manuel de Santa Cruz, Apuntes y documentos para la historia del tradicionalismo español, vols. 1-3, Sevilla 1979, p. 122

- ^ Julián Casanova, Carlos Gil Andrés, Twentieth-Century Spain. A History, Cambridge 2014, ISBN 9781107016965, p. 241. Other – supposedly less important departments of the ministry – were managed by Augusto Krahe (vocational education), Eugenio d’Ors (arts) and Javier Lasso de Vega (archives and libraries), Lorenzo Delgado Gómez-Escalonilla, Imperio de papel. Acción cultural y política exterior durante el primer franquismo, Madrid 1992, ISBN 9788400072438, p. 85

- ^ Heraldo de Zamora 15.09.39, available here

- ^ Villanueva Martínez 1998, p. 65

- ^ Villanueva Martínez 1998, p. 178

- ^ compare Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, Villanueva Martínez 1998, Martorell Pérez 2009, Rodón Guinjoan 2015, García Riol 2015

- ^ Correo de Mallorca 24.11.42, available here

- ^ Villanueva Martínez 1998, p. 178

- ^ compare his 1943 ticket at the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ La Almudaina 02.05.46, available here

- ^ compare his 1946 ticket at the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ Diario de Burgos 05.05.49, available here

- ^ compare his 1949 ticket at the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ El Diario Palentino 30.07.51, available here

- ^ Imperio 10.05.52, available here

- ^ compare his 1952 ticket at the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ El Adelanto 17.12.52, available here

- ^ Pueblo 17.02.54, available here

- ^ Pueblo 11.05.55, available here

- ^ compare his 1955 ticket at the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ Diario de Burgos 23.11.55, available here

- ^ El Diario Palentino 04.03.56, available here

- ^ Francisco Comín Comína, Rafael Vallejo Pousada, La reforma tributaria de 1957 en las Cortes franquistas, [in;] Investigaciones de Historia Económica 8 (2012), p. 156

- ^ Comín Comína, Vallejo Pousada 2012, p. 158

- ^ together with Rafael Díaz Llanos, Luis Arellano and Dionisio Martín. According to them, the measures proposed would go “en contra de toda la política agraria de la concentración” and against “productividad”, Comín Comína, Vallejo Pousada 2012, p. 161

- ^ the estate, named El Romeral, amounted to at least 80 ha, Diario de Burgos 19.07.56, available here. At that time he lived in the mansion in Torrelodones (some 30 km from centre of Madrid), which covered some 1,200 square metres, included a garden of 0.5 ha and a swimming pool. The mansion was designed by a well-known architect, Javier Lahuerta Vargas. De Toledo sold it in the late 1960s, J. M. Otxotorena Elizegi (ed.), Javier Lahuerta Vargas, Pamplona 1996, ISBN 9788489713024, p. 59

- ^ “Romualdo de Toledo pertenecía a la corriente posibilista del Conde Rodezno que se mostraba favorable a un pactismo que reconociese a Juan de Borbón Battenberg como pretendiente tradicionalista”, also “ambos [with Bau] no pertenecían a la linea oficial representada por Fal Conde, sino a la colaboracionista del conde de Rodezno”, José Luis Orella Martínez, El origen ideológico del personal del primer franquismo. El equipo de Burgos, [in:] Manuel Ortiz Heras (ed.), Memoria e historia del franquismo: V Encuentro de investigadores del franquismo, Madrid 2005, ISBN 8484273830, referred after the online draft, available here, p. 4

- ^ Santa Cruz 1978, p. 122

- ^ El Diario Palentino 12.02.55, available here

- ^ Diario de Burgos 10.03.57, available here

- ^ for 1965 see Pueblo 10.03.65, available here

- ^ Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, p. 25

- ^ compare his 1955 ticket at the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ during a brief period he served even as the interim president of EFE, Soon Jin Kim, EFE. Spain's World News Agency, New York 1989, ISBN 9780313267741, p. 114

- ^ Diario de Burgos 24.02.67, available here; in 1969 he still counted among members of the EFE board, Pueblo 03.12.69, available here

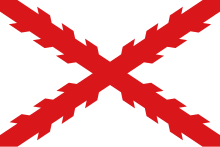

- ^ for Torres de Berrellin see El Diario Palentino 14.11.49, available here, for Jadraque see Nueva Alcarria 10.06.50, available here, for Almeria see Colegio público Romualdo de Toledo, [in:] DoCoMoMo service, available here, for Instituto Pedagogico in Valencia see BOE 11.07.50, available here, for Donostia see Herrera ikastetxea historia blog, available here. Until today almost all these institutions have been renamed, with the exception of Jadraque. Some claim its existence is incompatinle with Historical Memory Law, see Carmen Bachiller, Ocho colegios de Toledo mantienen nombres franquistas que incumplen la Ley de Memoria, [in:] ToledoDiario service 22.01.20, available here

- ^ at least one identified, in Lugo, Diario de Burgos 23.09.66, available here

- ^ El Diario Palentino 04.05.60, available here

- ^ Hoja Oficial de Lunes 17.04.67, available here

- ^ Libertad 26.03.60, available here

- ^ either with Sainz and Ibañez Martín, see along Caceres-Munoz, Groves, Gonzalez-Delgado 2024, p. 233, or with Ibanez, Peman, Krahe, d’Ors and Javier Lasso de Vega, Delgado Gómez-Escalonilla 1992, p. 85

- ^ e.g. de Toledo was prepared to purge the Barcelona schooling system already prior to Nationalist takeover of the city, The War in Spain 18.02.39, available here. As the result of purges, in 1939 April he was struggling to find enough enough teachers, El adelantado 25.04.39, available here. Nevertheless, he declared that “serán eliminados, con serenidad, pero con la máxima energía, todos aquellos maestros que, al envenenar la conciencia de nuestros niños, pretendieron formar una generación al servicio del ateísmo, marxismo, materialismo y antipatria, que han sido derrotadas por nuestro glorioso Ejército, a las órdenes de nuestro Caudillo”, quoted after Alberto Reig Tapia, La depuración "intelectual" del nuevo estado franquista, [in:] Revista de estudios políticos 88 (1995), p. 197

- ^ Caceres-Munoz, Groves, Gonzalez-Delgado 2024, p. 233

- ^ “para Sainz Rodríguez, la formación del maestro en este aspecto debe ser similar a la de otras profesiones que requieren estudios de rango universitario. Coincide, en este sentido, con la concepción de la reforma llevada a cabo en la Segunda República y con las que se están realizando en ese momento en algunos países europeos. Sin embargo, la tendencia representada por Romualdo de Toledo concibe la formación del maestro siguiendo el modelo tradicional francés, en el que esta preparación no requiere los estudios previos del bachillerato y los contenidos culturales necesarios”, María Dolores Peralta Ortiz, Los antecedentes de los estudios universitarios de Magisterio. Influencia del Plan Profesional de 1931, [in:] Tendencias pedagógicas 1 (1998), p. 211

- ^ Antonio Polo Blanco, Gobierno de las poblaciones en el primer franquismo (1939–1945), Cadiz 2006, ISBN 9788498280906, pp. 195-196. See also “due to lack of more detailed educational guidelines, during the early years of the Franco regime, the ideas expressed by some ideologists and pedagogues representative of Catholic traditionalism might have been taken as a reference”, and goes to quote Toledo, that “faced with lies about children’s conscious awareness, we uphold the need for a dogma: faced with man’s Rousseauism, we proclaim man’s fall into original sin. All these differences justify the pedagogical counterrevolution that Spain needs”, Gabriel Barceló Bauzá, Francisca Comas Rubi, Bernat Sureda Garcia, Abriendo la caja negra; la escuela pública española de postguerra, [in:] Revista de educación 371 (2016), p. 69

- ^ based on “doctrina social de la Rerum Novarum y la Quadragesimo Ano debía servir para inculcar en los pequeños la idea de amor y confraternidad social, hasta hacer desaparecer el ciego odio materialista”, Alejandro Mayordomo Perez (ed.), La educación y el proceso autonómico. Textos legales y jurisprudenciales, Madrid 1990, ISBN 8436918398, p. 67

- ^ George Volkan, WW1 and WW2. The nations, Mumbai 2024, ISBN 9789358835304, p. 144. During a 1943 conference in Vich de Toledo declared: “?Quereís un modelo de Escuela? Volvamos los ojos al monasterio en general y más especialmente al monasterio de Occidente creado por San Benito. Bien seguro estoy que no hay escuela moderna que le iguale ni en organización, ni en procedimiento, ni asiduo trabajo, ni, por último, en resultato positivo”, Javier Vergara Ciordia, Olegario Negrín Fajardo, Fermín Sánchez Barea, Beatriz Comella, Beatriz Comella Gutiérrez, Historia de la educación española, Madrid 2021, ISBN 9788418316357, p. 269

- ^ “sustituir una pedagogía por otra pedagogía”, this is “cimentada en verdad del pensamiento católico y apoyada en las más genuina y excelsa tradición hispana”, Mayordomo Perez 1990, p. 67

- ^ Frances Lannon, Privilege, Persecution, and Prophecy. The Catholic Church in Spain, 1875–1975, London 1987, ISBN 9780198219231, p. 221

- ^ Iker Rioja Andueza, Adoctrinamiento en los colegios y derogación del divorcio: así era el día a día de los ministros franquistas de Vitoria, [in:] El Diario 19.05.24, available here

- ^ Barceló Bauzá, Comas Rubi, Sureda Garcia 2016, p. 69

- ^ Esteban Vázquez Cano (ed.), La inspección y supervisión de los centros educativos, Zaragoza 2017, ISBN 9788436272383, p. 33

- ^ “la escuela debía educar a los niños y niñas en las ideas de disciplina, obediencia, jerarquía, sacrificio … reforzadas mediante una intensa actividad física canalizada a través del deporte y los juegos”, quoted after Morente Valero 1999, pp. 69-70

- ^ “En esencia, Romualdo de Toledo postulaba una enseñanza plenamente impregnada de la religión católica ... los ritos y prácticas religiosas debían ser constantes, incluyendo la asistencia conjunta de maestros y alumnos a misa los días de precepto ... niñas, a su vez, recibirían una educación especial para orientarlas hacia la función de madres y esposas ... se caracterizó por un nacionalismo exacerbado, excluyente e imperialista ... defensa de una sociedad armónica ... sociedad, por otra parte, que tiene su pilar más sólido en la familia, con la mujer en posición subordinada al hombre“, Morente Valero 1999, pp. 69-70

- ^ in 2019 senator Carles Mulet García (Coalició Compromís) demanded from Jadraque authorities explanations as to why its Colegio Público remains named after “Tiburcio Romualdo de Toledo, político fascista”, Solicitud de informe, 13.02.19, available here

- ^ José Ramón López Bausela, La escuela azul de Falange Española de las J.O.N.S. Un proyecto fascista desmantelado por implosión, Santander 2017, ISBN 9788481028041, p. 289

- ^ Ley Orgánica de 10 de abril de 1942, see Soraya Cruz Sayavera, El sistema educativo durante el Franquismo. Las leyes de 1945 y 1970, [in:] Revista Aequitas: Estudios sobre historia, derecho e instituciones 8 (2016), p. 38

- ^ Sainz Rodríguez opted for teachers acquiring higher education as designed by the republic, de Toledo opted for another specific system; eventually the latter got the upper hand, María Dolores Peralta Ortiz, Los proyectos sobre los estudios de magisterio en los comienzos del franquismo, [in:] Bordón: Revista de pedagogía 52/1 (2000), pp. 69-86

- ^ Peralta Ortiz 1998, pp. 207-211

- ^ Revista de educación 320 (1999), p. 33

- ^ Historia de la coeducación en España, [in:] EnVersalitas service 07.06.23, available here, also Cruz Sayavera 2016, p. 38. De Toledo was against coeducation as “the intellectual differences which Nature has created between the sexes will always persist”, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 211

- ^ Cruz Sayavera, 2016, p. 36

- ^ Mercedes Villanova Ribas, Xavier Moreno Juliá, Atlas de la evolución del analfabetismo en España, Madrid 1992, ISBN 8436921186, pp. 385-386, 390-391

- ^ Alba María López Melgarejo, La Junta Nacional contra el analfabetismo (1950–1970): un análisis documental, [in:] Educatio Siglo XXI 37/2 (2019), p. 270

- ^ Cruz Sayavera, 2016, p. 43

- ^ Irene Palacio, Irene Palacio Lis, Cándido Ruiz Rodrigo, Infancia, pobreza y educación en el primer franquismo, Valencia 1993, ISBN 9788437011981, p. 129

- ^ El Adelanto 26.08.39, available here, also Cruz Sayavera 2016, p. 38

- ^ e.g. he suggested that teachers in rural schools should have the rural background themselves, Teresa González Pérez, El discurso educativo del nacionalcatolicismo y la formación del magisterio español, [in:] Historia Caribe XII/33 (2018), p. 98

Further reading

[edit]- Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931–1939, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 9780521086349

- Soraya Cruz Sayavera, El sistema educativo durante el Franquismo. Las leyes de 1945 y 1970, [in:] Revista Aequitas: Estudios sobre historia, derecho e instituciones 8 (2016), pp. 31–62

- Francisco Morente Valero, Política educativa y represión del Magisterio en la España franquista (1936–1943), [in:] Spagna contemporanea 16 (1999), pp. 61–82

- Gabriel Barceló Bauzá, Francisca Comas Rubi, Bernat Sureda Garcia, Abriendo la caja negra; la escuela pública española de postguerra, [in:] Revista de educación 371 (2016), pp. 61–82

External links

[edit]- Carlists

- City councillors in the Community of Madrid

- 20th-century educational theorists

- FET y de las JONS politicians

- Francoists

- Grand Cross of the Order of Civil Merit

- Madrid city councillors

- Members of the Congress of Deputies of the Second Spanish Republic

- Members of the Cortes Españolas

- Members of the National Council of the FET-JONS

- News agency founders

- People from the Province of Guadalajara

- Perpetrators of political repression in Francoist Spain

- Politicians from Madrid

- Roman Catholic activists

- School founders

- Spanish refugees

- Spanish Roman Catholics

- Spanish anti-communists

- 20th-century Spanish businesspeople

- Spanish civil servants

- 20th-century Spanish educators

- Spanish educational theorists

- Spanish far-right politicians

- Spanish landowners

- Spanish meteorologists

- Spanish monarchists

- Spanish people of the Spanish Civil War (National faction)

- Spanish propagandists

- Spanish rebels

- University of Zaragoza alumni

![Jadraque, the only school named after de Toledo not renamed until today visible in bottom-right corner[180]](http://up.wiki.x.io/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8c/Jadraque_en_julio_de_2022_45.jpg/540px-Jadraque_en_julio_de_2022_45.jpg)