Roman–Parthian War of 194–198

| Parthian Campaigns of Septimus Severus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Roman–Parthian Wars | |||||||

The theatre of Septimius Severus' military campaigns | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Roman Empire | Parthian Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Septimius Severus |

Vologases V of Parthia Abgar VIII of Osroene | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| ...see section | ...see section | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

9–11 legions 13–16 vexillationes Some auxiliary units (Total: approx. 150,000 men) | Unknown | ||||||

| Sources in body text | |||||||

The Parthian campaigns of Septimius Severus (195-198) involved the Roman armies' success over the Parthians for supremacy over the nearby Kingdom of Armenia. After this defeat the Parthians were first defeated by the Roman armies of Severus's son, Caracalla (215–217), and then replaced in 224 by the Sassanid dynasty.

Historial context

[edit]Prelude

[edit]The Severan dynasty, which reigned over the Roman Empire between the end of the 2nd and the first decades of the 3rd century, from 193 to 235, with a brief interruption during the reign of Macrinus between 217 and 218, had its founder in Septimius Severus and its last descendant in Alexander Severus. The new dynasty was born from the ashes of a long period of civil wars (Year of the Five Emperors),[1] where three other contenders faced each other in addition to Septimius Severus (Didius Julianus, Pescennius Niger and Clodius Albinus).[2] Furthermore, in the nomination of the emperors there was a clear reference to the Antonine dynasty. The reason was to create a form of ideal continuity with the previous dynasty, almost as if there had been no interruption, not even with his predecessor Pertinax.[3]

Casus belli

[edit]Septimius Severus decided to invade Osroene in 195, since the Parthians had helped during 194 his direct rival to the imperial throne, Pescennius Niger, who had been defeated in three battles (at Cyzicus, Nicaea and Issus),[4][5][6] and in an attempt to take refuge among the Parthians and fleeing from Antioch, was reached and killed.[5] His head eventually found its way to Rome where it was displayed.[6]

Forces in the field

[edit]Roman forces

[edit]The operations of these years of war beyond that allowed the emperor himself to constitute three new legions:

directly involved others such as:

- Legio III Cyrenaica, III Gallica, IIII Scythica, VI Ferrata, X Fretensis, XII Fulminata, XIIII Gemina, XV Apollinaris and XVI Flavia Firma;

in addition to some vexillationes coming from other fronts such as:

- Legio I Adiutrix, I Italica, I Minervia, II Adiutrix, II Traiana, III Augusta, V Macedonica, VII Claudia Pia Fidelis, VIII Augusta, XI Claudia Pia Fidelis, XIII Gemina, XXII Primigenia and XXX Ulpia Victrix.[8]

The total forces deployed by the Roman Empire may have exceeded 150,000 men involved; of these, half were legionaries (from as many as 24-25 legions), the remainder were auxiliaries.[9]

Parthian forces

[edit]The Parthian units that took part in Septimus Severus's campaigns between 194 (or 195) and 198 AD are unknown.

Course of the campaign

[edit]First campaign (194–195)

[edit]

Adiabene and Osroene had rebelled against Rome, laying siege to the city of Nisibis. However, when they learned that Severus had defeated and killed Pescennius Niger, they decided to ask for his forgiveness,[10] although they were not willing to free the Roman garrisons taken from Niger. Indeed, they demanded that the Romans leave the rest of their country free. For this reason Severus did not hesitate to wage war against them.[10] In fact, he left Antioch for the Euphrates, crossing it at Zeugma during that particularly hot summer, so much so that the Roman army risked losing numerous soldiers due to dehydration.[11]

After an initial clash, he managed to liberate the city of Nisibis, which had evidently been Roman since the time of the campaigns of Lucius Verus.[12] He then decided to divide the army into three more sections, sending his subordinates, Lateranus, Julius Laetus and Candidus in different directions to subdue all the cities that had previously rebelled.[13] Once they returned after having achieved their objective, Severus divided the army again between Laetus, Publius Cornelius Anullinus, and Probus and sent them against a certain Arche,[14] evidently a king of the area, perhaps belonging to the population of the Arabs of the fortified city of Hatra,[15] besieged at least twice by Severus (also during the campaign of 197–198).[16]

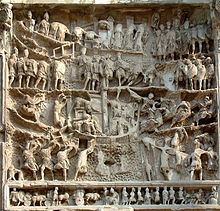

Some of these scenes are represented in the first south-east panel of the triumphal arch located near the Curia Julia in the Roman Forum. At the end of the war operations he reunited the province of Mesopotamia (which included only Osroene and Adiabene) by placing two of the three new legions just created (the Legio I and the III Parthica) as garrison there, under the leadership of a prefect of equestrian rank. For these successes he assumed the titles of Adiabenicus and Arabicus[17][18] in 195 AD.[19]

Second campaign (197–198)

[edit]| Septimus Severus: denarius[20] | |

|---|---|

| |

| L SEPT SEV PERT AVG IMP VIII, laureate head right, in military uniform (Paludamentum) | Profectio AUG, Septimius Severus on horseback setting out for the Eastern front with a lance in his hand. |

| 2.85 g, minted in 197. | |

In early 197 Severus left Rome and sailed to the east. He embarked at Brundisium and probably landed at the port of Aegeae in Cilicia,[21] travelling on to Syria by land. He immediately gathered his army and crossed the Euphrates.[22] Abgar IX, titular King of Osroene but essentially only the ruler of Edessa since the annexation of his kingdom as a Roman province,[23] handed over his children as hostages and assisted Severus' expedition by providing archers.[24]

The second campaign was conducted from the summer of 197 to the spring of 198.

- 197 campaign

- The campaign had begun because of a new siege of the Parthian armies to the city of Nisibis, which resisted thanks to the abilities of Severus's young commander, Julius Laetus, who also participated in the previous campaign of 195.[25] The armies of Severus, in full force, crossed the Euphrates once again near Zeugma and headed with large siege engines towards Edessa, which opened its gates to him as a sign of welcome, and sent him high dignitaries and banners as an act of submission. The king of Osroene Abgar VIII then promised to supply allied forces for the offensive in Mesopotamia.[25]

The king of the Parthians, Vologases V, having learned that Severus was approaching Nisibis, decided to leave. In the meantime, the Roman emperor, having reached the city, now free from the siege, had an unexpected encounter. Cassius Dio recounts, in fact, that here he found an enormous wild boar, which had killed a Roman knight, who had tried in vain to kill it. It took the intervention of about thirty soldiers to capture it and bring it to Severus.[25]

Cassius Dio's records also tell us how he defined the Parthians "lazy" and "weak" for always retreating when Severus "showed up".[25]

Severus, having built a fleet, crossed the Euphrates with extremely fast ships, where he first reached Dura Europos, continued to Seleucia which he occupied, after having put to flight the cataphract cavalry of the Parthians.[25] The advance continued with the capture of Babylon[26] which shortly before had been abandoned by the enemy forces and, towards the end of the year, even the capital of the Parthians, Ctesiphon,[26] was placed under siege. The city, now surrounded, tried in vain to resist the impressive military machine that the Roman emperor had managed to put together (about 150,000 armed men). When it was now close to capitulation, King Vologases V abandoned his men and fled towards the interior of his territories. The city was sacked and many of its inhabitants were killed by Roman soldiers or sold into slavery,[25] as had happened in the past at the time of Trajan (in 116) and Lucius Verus's (in 165).[25][12]

- 198 campaign

- Severus spent the winter near the Parthian capital and around February-March he decided to go up the Tigris to return to the Roman borders.[25] During the retreat he tried in vain for the second time to besiege the important stronghold of Hatra, but again without success, since many of his machines had been destroyed and many of his men were wounded.[27] It is also said that during this war he put to death two important people. They were a certain Julius Crispus, a tribune of the praetorium, because he had complained about the long war, and had quoted Virgil, according to whom "while Turnus wanted to marry Lavinia, we all die unheard", referring to the complaints of the soldiers; the other man he put to death, this time out of jealousy, was precisely that Julius Laetus who had defended Nisibis during these campaigns, perhaps because he was brave and loved by the soldiers, who had declared that they would not continue the war if it were not for Laetus who led them.[27]

Cassius Dio reports, finally, that Severus decided shortly after, to place the city of Hatra under siege once again, taking with him large quantities of food and siege engines, but on this occasion it is said that, not only did he lose a large amount of money for the preparation of the expedition, but also numerous war machines (apart from those of a certain Priscus),[28] and furthermore, the emperor himself, during an attack on the enemy walls, almost risked his life, finally deciding to withdraw definitively and go to Egypt.[29] Following the general success of the campaign, however, he earned the title of Parthicus maximus.[17]

Result of the campaign

[edit]Analysis

[edit]Especially after 197, Severus marched through northern Mesopotamia, re-annexing it to the empire and placing at its head a prefect of equestrian rank.[30][31][32] Shortly afterwards he led the army towards Ctesiphon, sacking it[33] and reducing most of its inhabitants to slavery [34] or also deporting them.[35] During his time in the east, though, Severus also expanded the Limes Arabicus, building new fortifications in the Arabian Desert from Basie to Dumatha.[36][37]

References

[edit]- ^ Rahman 2001[page needed]

- ^ Birley 1999, pp. 89–128.

- ^ Inscriptions CIL VIII, 14395, CIL XI, 8, AE 1894, 49, AE 1991, 1680 and numerous others.

- ^ Bowman 2005, p. 4.

- ^ a b Southern 2001, p. 33.

- ^ a b Potter 2004, p. 104.

- ^ Sage 2020, p. 81.

- ^ González 2003, p. 728.

- ^ Le Bohec 2001, pp. 34–45.

- ^ a b Cassius Dio, Roman history, LXXV, 1, 2.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman history, LXXV, 2, 1–2.

- ^ a b Scarre 1995a, pp. 97–99.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman history, LXXV, 2, 3.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman history, LXXV, 3, 2.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman history, LXXIV, 11, 2.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman history, LXXVI, 10-11.

- ^ a b Inscriptions AE 1893, 84, CIL VIII, 24004, AE 1901, 46, AE 1906, 21, AE 1922, 5, AE 1956, 190, CIL VIII, 1333 (p. 938).

- ^ Scarre 1995b, p. 131.

- ^ Inscription CIL XI, 8.

- ^ Roman Imperial Coinage, Septimius Severus, IVa, 494; BMC 466. Cohen 580.

- ^ Hasebroek 1921, p. 111.

- ^ Historia Augusta, "Life of Septimius Severus", 16.1.

- ^ Birley 1999, p. 115.

- ^ Birley 1999, p. 129.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cassius Dio, Roman history, LXXVI, 9.

- ^ a b Zosimus, Historia nova, I, 8.2.

- ^ a b Cassius Dio, Roman history, LXXVI, 10.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman history, LXXVI, 11.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman history, LXXVI, 12.

- ^ Hasebroek 1921, p. 130.

- ^ Birley 1999, p. 130.

- ^ Birley 1999, p. 153.

- ^ Daryaee 2010, p. 249.

- ^ Hasebroek 1921, p. 153.

- ^ Kröger 1993, pp. 446–448.

- ^ Birley 1999, p. 134.

- ^ Hasebroek 1921, p. 134.

Sources

[edit]Primary or ancient sources

[edit]- Cassius Dio, Roman history, LXXVI.

- Herodian, Storia dell'impero dopo Marco Aurelio.

- Roman Imperial Coinage, Septimius Severus, IVa.

- Zosimus, Historia nova, I.

Secondary or modern sources

[edit]- Birley, Anthony R. (1999) [1971]. Septimius Severus: The African Emperor. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-16591-4.

- Rahman, Abdur (2001). The African Emperor? The Life, Career, and Rise to Power of Septimius Severus, MA thesis. University of Wales Lampeter.

- Southern, Pat. (2001). Routledge (ed.). The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Potter, David Stone (2004). Routledge (ed.). The Roman Empire at Bay, AD 180-395.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Bowman, Alan K. (2005). Cambridge University Press (ed.). The Cambridge Ancient History: The Crisis of Empire, A.D. 193-337.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Le Bohec, Yann (2001). L'esercito romano (in Italian). Carocci. ISBN 8843017837.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - González, Julio R. (2003). Historia de las legiones romanas (in Spanish). Madrid: Signifer Libros. ISBN 8493120782.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Sage, Michael M. (June 30, 2020). Septimius Severus & The Roman Army. Yorkshire, Philadelphia: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-3990-0323-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Scarre, Chris (September 1, 1995). The Penguin Historical Atlas of Ancient Rome. London: Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 0140513299.

- Scarre, Chris (1995). Chronicle of the Roman Emperors: The Reign-by-reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial Rome. London & New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Hasebroek, Johannes (1921). Untersuchungen zur Geschichte des Kaisers Septimius Severus. Heidelberg: C Winter. OCLC 4153259.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Daryaee, Touraj (2010). "Ardashir and the Sasanians' Rise to Power". Anabasis: Studia Classica et Orienta. University of California: 236–255.

- Kröger, Jens (1993). "Ctesiphon". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 4. pp. 446–448.