Roca–Runciman Treaty

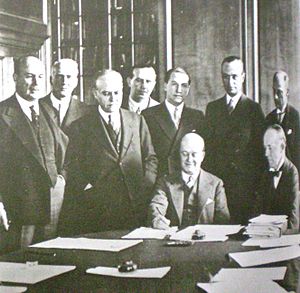

The Roca–Runciman Treaty was a commercial agreement signed on 1 May 1933 between Argentina and the United Kingdom signed in London by the Vice President of Argentina, Julio Argentino Roca, Jr., and the president of the British Board of Trade, Sir Walter Runciman.

As a byproduct of Black Tuesday and the Wall Street crash of 1929, the United Kingdom, principal economic partner of Argentina in the 1920s and 1930s, took measures to protect the meat supply market in the Commonwealth. At the Imperial Preference negotiations in Ottawa, bowing to pressure, mainly from Australia and South Africa, Britain decided to severely curtail imports of Argentine beef. The idea was to enact monthly cuts of 5% during the first year of the agreement.[1] The plan provoked an immediate outcry in Buenos Aires, and the government dispatched Vice-President Roca and a team of negotiators to London.

On 1 May 1933, they concluded a bilateral treaty known as the Roca-Runciman Treaty.[2] The Argentine Senate ratified this agreement by Law #11,693. The treaty lasted three years and was renewed as the Eden-Malbrán Treaty of 1936, which gave additional concessions to Britain in return for lower freight rates on wheat.[3]

The treaty ensured beef export quotas that were equivalent to the levels sold in 1932 (the lowest point in the Great Depression), strengthening the commercial ties between Argentina and Britain.

- Argentina was assured of an export quota of no less than 390,000 metric tonnes of refrigerated beef, but 85% of the beef exports were to be made through foreign meat packers. Britain "would be agreeable to permit" the participation of Argentine meat packers of up to 15%.

- Argentina would give to British companies "a benevolent treatment towards insuring the greatest economic development of the country and the deserved protection to the interests of these companies."[4]

- As long as there were currency controls in Argentina (limiting the sending of money abroad), everything that Britain would pay for purchases in Argentina could be returned to the country by deducting a percentage from payments to the foreign debt.

- Argentina would keep free of duties imports of coal and other goods imported from Britain at the time and vowed to buy coal only from Britain.

- Argentina agreed not to increase import duties on all British goods or reduce the fees paid to the British railways in Argentina and exemptions from certain labour legislation, such as the funding of pension programmes.

The treaty had strong political repercussions in Argentina later triggering a conflict from the denunciations of Senator Lisandro de la Torre.

From the treaty, Britain's exporters received more benefits than Argentinian exporters. For only the promise of purchasing Argentine beef at the reduced levels of the Depression era, Argentina agreed to reduce tariffs on almost 350 British goods to the rates of 1930 and to refrain from imposing duties on main imports such as coal, as already mentioned.[1]

| Year | Argentine imports | Argentine exports |

|---|---|---|

| 1927 | 19.4 | 28.2 |

| 1930 | 19.8 | 36.5 |

| 1933 | 23.4 | 36.6 |

| 1936 | 23.6 | 35.0 |

| 1939 | 22.2 | 35.9 |

Source: Colin, Lewis – "Anglo-Argentine Trade 1945-1965"

as quoted in "Argentina in the Twentieth Century" by David Rock (London 1975) pg 115

References

[edit]- ^ a b Rock, David (1987). Argentina, 1516-1987: From Spanish Colonization to Alfonsín. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520061781.

- ^ Rennie, Ysabel Fisk (1945). The Argentine Republic. Macmillan.

- ^ Rock, David (1985). Argentina, 1516-1982: From Spanish Colonization to the Falklands War. University of California Press. p. 225. ISBN 9780520051898.

- ^ Rins, Elba Cristina; Winter, María Felisa (1997). La Argentina una historia para pensar 1976-1996. Kapelusz. ISBN 9789501325690.