Riverine rabbit

| Riverine rabbit[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Bunolagus monticularis in Western Cape, South Africa | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Lagomorpha |

| Family: | Leporidae |

| Genus: | Bunolagus Thomas, 1929 |

| Species: | B. monticularis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Bunolagus monticularis (Thomas, 1903)

| |

| |

| IUCN distribution of the Riverine rabbit

Extant (resident)

| |

The riverine rabbit (Bunolagus monticularis), also known as the bushman rabbit or bushman hare, is a species of rabbit found in patches of thick vegetation in the Karoo Desert of South Africa's Western and Northern Cape provinces. It is the only member of the genus Bunolagus. The most recent estimates of the species' population range from 157 to 207 mature individuals, and 224 to 380 total.

First identified in 1903 as a member of the hares, the riverine rabbit is a medium-sized (33.7 to 47.0 centimetres (13.3 to 18.5 in) long) rabbit. Its fur has a unique dark brown-colored stripe from the edge of its mouth up towards the base of its ears, and a white- to gray-colored ring around each eye. It is nocturnal and herbivorous, and its diet consists of grasses, flowers and leaves, most of which are dicotyledons. The riverine rabbit will dig burrows in the soft alluvial soils of its habitat near seasonal rivers, using them for protection from the heat and for females to nest and protect the young. Though they live alone throughout the year, riverine rabbits are polygamous.

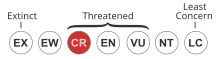

Unlike most rabbits, female riverine rabbits produce only one to two offspring per year. This, along with habitat loss from agricultural development, soil erosion, and predators contributes to its classification as critically endangered, the most severe classification used by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Currently, there are conservation plans being enacted to help with its decreasing population and habitat.

Taxonomy and evolution

[edit]The riverine rabbit's scientific name is Bunolagus monticularis.[3] It was first described by Oldfield Thomas in 1903 as Lepus monticularis with the type locality of Deelfontein, Cape Colony, South Africa;[4] it was separated into its own species in 1929.[5] Some common names referring to it are the bushman hare and the bushman rabbit.[6] This rabbit also has names in Afrikaans, such as boshaas and vleihaas, referring to the rabbit's habitats being moist and dense - bos meaning "forest" or "thicket", vlei meaning "swamp", and haas meaning "hare".[7] Other names it has are pondhaas and oewerkonyn.[5]

Phylogeny

[edit]Genetically, the closest relations of Bunolagus monticularis are to the Amami rabbit, the hispid hare, and the European rabbit.[7] A cladogram showing this is from Matthee et al., 2004, based on nuclear and mitochondrial gene analysis.[8]

| Lagomorphs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bunolagus is not well known in the fossil record. It may date back to the middle Pleistocene, 0.4 million years ago in South Africa. Its distribution has likely always been very restricted. The only known fossils of the genus have as of 2007 been reconsidered as small specimens of Lepus.[9]

Characteristics

[edit]The riverine rabbit is native to the Karoo desert in South Africa.[10] It has a similar appearance to hares (lagomorphs in the genus Lepus), particularly in the characteristics of the skull; it most closely resembles the Cape hare (Lepus capensis) in its morphology, but not in its fur patterns. It is distinct from the red rock hares,[5] some of which overlap it in distribution;[11][2] in its first description, it was noted as being about the same size as the Natal red rock hare (Pronolagus crassicaudatus),[4] though it has been later described as smaller than all red rock hares besides Smith's red rock hare (P. rupestris).[12]

Bunolagus monticularis has an adult head and body length of 33.7 to 47.0 centimetres (13.3 to 18.5 in). It typically has a dark brown stripe running from the lower jaw over the cheek and upwards towards the base of the ears and a white ring around each eye.[5] The nuchal patch, as well as the limbs and lower flanks, are rufous in color.[13] It has a brown woolly tail, and cream to greyish-coloured fur on its undersides. The hind feet are broad and club-shaped.[14] Its dental formula is 2.0.3.31.0.2.3 × 2 = 28, as is the case with all rabbits.[15] Its tail is pale brown with a tinge of black toward the tip. Its coat is soft and silky, more so than that of hares, and is of a reddish-brown to black shade. Its limbs are short and heavily furred, with the hind foot measuring 9–12 centimetres (3.5–4.7 in).[5] The ears measure 11–12 centimetres (4.3–4.7 in)[16] and are rounded at the tips.[13] The species displays sexual dimorphism in the size of individual rabbits, with males weighing approximately 1.5 kilograms (3.3 lb) and females weighing about 1.8 kilograms (4.0 lb).[14]

Habitat

[edit]

Bunolagus monticularis is found in only a few places in the Karoo Desert. The riverine rabbit prefers to occupy areas of dense vegetation in river basins and shrubland. It feeds on the dense shrubland, and the soft soil allows for it to create burrows and dens for protection, brooding young, and thermoregulation. The riverine rabbit lives in very dense growth along seasonal rivers in the central semi-arid Karoo region of South Africa. Its habitat regions are tropical and terrestrial while its terrestrial biomes are desert or dune and scrub forest.[14] Two of the most common plants in its habitat are Salsola glabrescens, Amaranthaceae (34·8%) and Lycium spp. Solanaceae (11·2%).[16]

They appear and live specifically in riverine vegetation on alluvial soils adjacent to seasonal rivers,[17] though studies have found this habitat to be sixty-seven percent fragmented in certain areas. Currently the habitat is decreasing in size, contributing to this species being classified as endangered. As of 2016, it was estimated that the riverine rabbit occupied a region spanning only 86 square kilometres (33 sq mi).[18] The primary reason for the decline in habitats is due to cultivation and livestock farming. Major threats to this species comes from loss and degradation of habitat. Over the last hundred years, over two-thirds of their habitat has been lost. Today only five hundred mature riverine rabbits are estimated to be living in the wild. Removal of the natural vegetation along the rivers and streams prevent the rabbits from being able to construct stable breeding burrows. This is because of the loss of the soft alluvial top soils, which are necessary for the construction of these. Another cause of damage and loss to their habitats comes from overgrazing of domestic herbivores, which also causes degradation and fragmentation of the land. Without suitable habitat they have a lower rate of survival.[6] A 1990 study put forth that the remaining habitat was thought to only be able to support 1,435 rabbits.[19]

Behaviour and ecology

[edit]Riverine rabbits are solitary and nocturnal.[16] At night, they feed on flowers, grasses, and leaves. During the day, they rest in forms. The rabbit practices cecotrophy, producing two types of droppings—hard droppings during the night, and soft droppings during the day, which are taken directly from the anus and swallowed. These soft droppings provide the rabbit with nutrients produced by bacteria in the hindgut and recycled minerals.[10]

The riverine rabbit is polygamous, but lives and browses for food alone. It has intra-sexually exclusive home ranges: the males' home ranges overlap slightly with those of various females, with males having an average home range size roughly 60% larger than females (20.9 hectares (52 acres) compared to 12.9 hectares (32 acres)). The breeding season takes place between August and May, wherein females will make a grass- and fur-lined nest in a burrow, blocking the entrance with soil and twigs to keep out predators. The average length of a generation is 2 years; in captivity, individuals have been recorded as living up to 5 years.[20]

Diet

[edit]

The riverine rabbit mainly feeds through browsing.[14] When grasses are available during the wet season, they are the rabbit's preferred food, but most of the time the diet of Bunolagus monticularis is restricted to the flowers and leaves of dicotyledons in the Karoo Desert. These include species in the families Asteraceae, Amaranthaceae, and Aizoaceae,[21] particularly salt-loving plants such as the salsola and lycium that grow along seasonal rivers in the desert. Aside from their conventional food intake, they also consume soft day-time droppings that come directly from the anus in the process known as cecotrophy. This is advantageous because their faeces contains vitamins, such as various B vitamins, produced by the bacteria in the hindgut, as well as recycled nutrients such as calcium and phosphorus.[14]

Populations in the more northern areas of the species' distribution are more strongly associated with the vegetation that grows narrowly along seasonal rivers; those in the southern parts of its distribution are not as closely tied to this type of vegetation and have been observed feeding on newly grown plants in fallow land.[5]

Reproduction

[edit]The riverine rabbit has a polygamous mating system, wherein males will mate with multiple females. Based on limited observations, the breeding season takes place from August through May, and gestation takes 35 to 36 days. It bears its young underground for protection, relying on soft soil in the flood plains of its habitat to construct its breeding burrows. These burrows are lined with fur and grass, and the entrance is closed off with dirt and twigs for camouflage from predators. This burrow is 20–30 centimetres (7.9–11.8 in) long, and the nesting chamber within is 12–17 centimetres (4.7–6.7 in) wide.[16] The riverine rabbit has 44 diploid chromosomes,[5] as do several closely related rabbits, the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus)[22] and hispid hare (Caprolagus hispidus).[23]

The offspring that the rabbit produces, one to two per litter, are born altricial, or bald, blind, and helpless, and weighs from 40 to 50 grams. The helpless offspring stays with the mother until it is capable of living on its own and fending for itself.[5] The low breeding rate of only one to two offspring per year is unlike most other rabbits and has led to attempts to increase numbers of this endangered species.[14] A breeding colony has been established at the De Wildt Cheetah and Wildlife Centre near Pretoria.[24]

Predators and competitors

[edit]

The riverine rabbit is hunted by Verreaux's eagles (Aquila verreauxii),[14] African wildcats (Felis sylvestris lybica), and caracals (Caracal caracal), the latter two of which have seen population increases due to the decline of the black-backed jackal (Lupulella mesomelas) in the region.[16] To escape predation, the riverine rabbit makes use of forms during the day to stay hidden—shallow depressions in the soil made under vegetation. It can also jump over one meter high while being pursued.[7]

Relationship with humans

[edit]The riverine rabbit provides benefits for farmers. It causes the riverine vegetation that it eats to bind to the soil and prevent soil erosion through flooding. Through this process, the vegetation allows for filtration of rainwater into groundwater. This benefits farmers, who rely on windmills to draw up water from the ground for their livestock. Without the riverine rabbit or other animals that browse upon the same plants in the same manner, these benefits are lost.[14] The species is suspected to be hunted for bushmeat by farm workers and for sport.[20]

Endangerment

[edit]Extent

[edit]The riverine rabbit is in extreme danger of extinction. In 1981, it was first labelled as an endangered species. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classified it under the most severe category of endangerment (aside from extinction), critically endangered, in 2002.[7] The National Red List of South Africa maintained by the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) uses this same classification. Both organizations maintain this position as of their most recent evaluations from 2016.[20] It has a population of 157 to 207 mature rabbits and up to 380 overall, which continues to decline. This species' population is divided into several isolated groups, about 12 in total, all with less than 50 rabbits in each. These isolated populations are protected by jackal-proof fencing and separated by major agricultural projects.[2]

Causes

[edit]The decline in the riverine rabbit population is largely due to the alteration of its historically limited[9] habitat. Over half of the rabbit's range has been rendered unable to support the species due to agricultural development since 1970. The range of habitable area continues to decline, and in 2008 it was predicted that over the next 100 years, one fifth of habitable area will be lost. The reason for this ongoing destruction of the rabbit's habitat is the practise of raising animals for commercial reasons in the area, causing the environment to be transformed to serve this end. Another ongoing threat to the rabbit is how the isolated groups are divided up because fields in the area often have fencing which is impermeable to this species, designed to keep out jackals.[6] The remaining land left to support the species is being damaged by climate change. Populations are further reduced through anthropogenic means. Hunting and accidental trapping by farmers is a direct cause of population decline,[25] while removal and exploitation of trees limits the rabbit's opportunities for shelter from heat and predators. Structures on rivers like dams isolate subpopulations from each other, discouraging population regeneration. Soil erosion caused by other animals grazing and feeding on local vegetation can also impact the availability of food for the rabbit.[7] Relatively recent threats to the riverine rabbit are fracking and wind farm developments in the Nama Karoo, the former of which could alter the region's hydrology, and both of which will further fragment the available habitat.[5]

Conservation

[edit]Current efforts

[edit]Relative to other similar species, known information about key aspects of the riverine rabbit, such as behaviour and diet, is deficient. Conservation efforts are better informed by researching this species and involving local communities, particularly farmers.[7] The current plan to protect the remaining members of the population has been criticized, with experts claiming that a large part of the remaining land that can support the rabbit is outside the current area being preserved for it.[19] Other efforts include engaging and educating local farmers so that they act in a way which reduces harm to the species. Efforts have been made to form agreements with landowners that ensure that certain measures are taken to help the rabbit population.[7] Thorough monitoring of rabbit populations is needed to accurately estimate needed conservation efforts, a task that has been carried out largely by the Endangered Wildlife Trust.[25] One location being monitored is Sanbona Wildlife Reserve, a protected wilderness area with a successful breeding population where the species is being researched.[14]

Recommended action

[edit]The IUCN recommends several further conservation measures, demonstrating that current actions are not adequate. They recommend capturing the animal as to safely allow it to reproduce without danger of predators or starvation. They also recommend different methods of managing the habitat and the population in the wild. Finally they recommend further efforts of informing the local populace as to how to protect the rabbit. The red list also notes that further research is needed into its ecology and into the conservation actions that would be most effective.[6] Conservation of the rabbit's habitat and maintaining interconnection between populations is important to the preservation of the species, as its complex genetic structure makes breeding with groups outside of the species difficult, if not impossible.[5]

A 2016 assessment by SANBI noted that there were increased sightings of the species within its extent of occurrence, and that camera traps and further observations were needed to confirm the spread of subpopulations in regions south and eastward of the rabbit's native range.[20]

References

[edit]- ^ Hoffman, R.S.; Smith, A.T. (2005). "Order Lagomorpha". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c Collins, K.; Bragg, C.; Birss, C. (2019). "Bunolagus monticularis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T3326A45176532. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T3326A45176532.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Wilson, Don (2005). "Bunolagus monticularis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- ^ a b Thomas, Oldfield (1903-01-01). "On a remarkable new hare from Cape Colony". Annals and Magazine of Natural History (7). 11 (61): 78–79.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bragg, Christy J.; Matthee, Conrad A.; Collins, Kai (2018). "Bunolagus monticularis (Thomas, 1903) Riverine Rabbit". In Smith, Andrew T.; Johnston, Charlotte H.; Alves, Paulo C.; Hackländer, Klaus (eds.). Lagomorphs: Pikas, Rabbits, and Hares of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 90–93. ISBN 978-1-4214-2341-8. LCCN 2017004268.

- ^ a b c d "Bunolagus monticularis: South African Mammal CAMP Workshop". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. 2008. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T3326A43710964.en.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Bunolagus monticularis (Riverine rabbit)". Biodiversity Explorer. Archived from the original on 6 October 2010.

- ^ Matthee, Conrad A.; et al. (2004). "A Molecular Supermatrix of the Rabbits and Hares (Leporidae) Allows for the Identification of Five Intercontinental Exchanges During the Miocene". Systematic Biology. 53 (3): 433–477. doi:10.1080/10635150490445715. PMID 15503672.

- ^ a b Winkler, Alisa J.; Avery, D. Margaret (2010). "Lagomorpha". In Werdelin, Lars; Sanders, William Joseph (eds.). Cenozoic Mammals of Africa. University of California Press. pp. 309–311. ISBN 978-0-520-25721-4.

- ^ a b "Riverine rabbit". EDGE of Existence.

- ^ Johnston 2018, pp. 108–113

- ^ Sen, S.; Pickford, M. (2022). "Red Rock Hares (Leporidae, Lagomorpha) past and present in southern Africa, and a new species of Pronolagus from the early Pleistocene of Angola" (PDF). Communications of the Geological Survey of Namibia. 24: 89.

- ^ a b Schai-Braun & Hackländer 2016, p. 72.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Awaad, Rania (2007). "Bunolagus monticularis". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2025-02-13.

- ^ Bertonnier-Brouty, Ludivine (3 July 2019). Dental development and replacement in Lagomorpha (Doctorate thesis). University of Lyon. Retrieved 16 February 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Schai-Braun & Hackländer 2016, p. 112.

- ^ Schai-Braun & Hackländer 2016, p. 75.

- ^ Schai-Braun & Hackländer 2016, p. 107.

- ^ a b Duthie, A.G; Skinner, J. D.; Robinson, T.J (1990). "The distribution and status of the riverine rabbit, Bunolagus monticularis, South Africa". Biological Conservation. 47 (3): 195–202. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(89)90064-5.

- ^ a b c d Collins, Kai; Bragg, Christy; Birss, Coral; Matthee, Conrad; Nel, Vicky; Hoffmann, Michael; Roxburgh, Lizanne; Smith, Andrew (May 2016), Child, MF; Roxburgh, L; Do Linh San, E; Raimondo, D; Davies-Mostert, HT (eds.), "Bunolagus monticularis Thomas Bayne, 190", The Red List of Mammals of South Africa, Swaziland and Lesotho, South Africa: South African National Biodiversity Institute and Endangered Wildlife Trust

- ^ Schai-Braun & Hackländer 2016, p. 89.

- ^ Delibes-Mateos, Miguel; Villafuerte, Rafael; Cooke, Brian D.; Alves, Paulo C. (2018). "Oryctolagus cuniculus (Linnaeus, 1758) European Rabbit". In Smith, Andrew T.; Johnston, Charlotte H.; Alves, Paulo C.; Hackländer, Klaus (eds.). Lagomorphs: Pikas, Rabbits, and Hares of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-2341-8. LCCN 2017004268.

- ^ Smith, Andrew T.; Johnston, Charlotte H. (2018). "Caprolagus hispidus (Pearson, 1839) Hispid Hare". In Smith, Andrew T.; Johnston, Charlotte H.; Alves, Paulo C.; Hackländer, Klaus (eds.). Lagomorphs: Pikas, Rabbits, and Hares of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 93–95. ISBN 978-1-4214-2341-8. LCCN 2017004268.

- ^ "Riverine Rabbit". Archived from the original on 2015-05-06. Retrieved 2015-10-03.

- ^ a b Starzak, Kelly. "In South Africa, rare riverine rabbits are ready for their closeup". Earth Touch News Network. Retrieved 2017-11-02.

Bibliography

[edit]- Collins, Kai; Du Toit, Johan T (2016). "Population status and distribution modelling of the critically endangered riverine rabbit (Bunolagus monticularis)". African Journal of Ecology. 54 (2): 195–206. Bibcode:2016AfJEc..54..195C. doi:10.1111/aje.12285. hdl:2263/55988.

- Hoffman, R.S.; Smith, A.T. (2005). "Order Lagomorpha". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Macdonald, David Whyte (2001). The New Encyclopedia of Mammals. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850823-6.

- Platt, John R. "New Population of Critically Endangered Rabbits Found in (of All Places) a Nature Reserve." Scientific American Blog Network, 7 Jan. 2014, https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/extinction-countdown/new-population-of-critically-endangered-rabbits-found-in-of-all-places-a-nature-reserve/.

- "Riverine Rabbit - Bunolagus monticularis - Overview." Encyclopedia of Life, Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History, https://www.eol.org/pages/311977/overview.

- "Riverine Rabbit, Bushman Rabbit, Bushman Hare." Bunolagus monticularis : WAZA : World Association of Zoos and Aquariums, WAZA, https://www.waza.org/en/zoo/visit-the-zoo/rodents-and-hares/bunolagus-monticularis.

- Starzak, Kelly. "In South Africa, Rare Riverine Rabbits Are Ready for Their Closeup." Earth Touch News Network, Earth Touch, 23 Feb. 2015, https://www.earthtouchnews.com/conservation/endangered/in-south-africa-rare-riverine-rabbits-are-ready-for-their-closeup/.

- Johnston, Charlotte H. (2018). Smith, Andrew T.; Johnston, Charlotte H.; Alves, Paulo C.; Hackländer, Klaus (eds.). Lagomorphs: Pikas, Rabbits, and Hares of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-2341-8. LCCN 2017004268.

- Schai-Braun, S. C.; Hackländer, K. (2016). "Family Leporidae (Hares and Rabbits)". In Wilson, D.E.; Lacher, T.E.; Mittermeier, R.A. (eds.). Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 6. Lagomorphs and Rodents I. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. pp. 62–149. ISBN 978-84-941892-3-4.