Rail freight transportation in New York City and Long Island

From the start of railroading in America through the first half of the 20th century, New York City and Long Island were major areas for rail freight transportation. However, their relative isolation from the mainland United States has always posed problems for rail traffic. Numerous factors over the late 20th century have caused further declines in freight rail traffic. Efforts to reverse this trend are ongoing, but have been met with limited success.

The New York and Atlantic Railway currently operates all rail freight on the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR)'s rights-of-way on Long Island. CSX Transportation also operates within New York City, as do several shortline railroads including a car float across the harbor.

History

[edit]Early days

[edit]

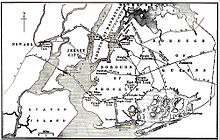

In part because of its easily accessible harbor and its canal connections to the interior, New York City and its surrounding area early on became the largest regional economy in North America. As railroads developed in the 19th century, serving New York City market was vital, but problematic. The Hudson River, a mile-wide (1.6 km) estuary near the city, a section also called the North River, presents a formidable barrier to rail transportation. As a result, most railroads terminated their routes at docks on the New Jersey shore (see 1900 map).[1] Ferries brought rail passengers to and from the city, while car float barges carried freight cars across the Hudson—on the order of one million carloads of freight per year.[2]

One exception was a New York Central Railroad line on the east bank of the Hudson that extended into Manhattan for freight service. The West Side Line, as it was called, brought freight cars to docks, warehouses and industries along Manhattan's west shore. Its southern portion included the High Line, a grade-separated viaduct that replaced the street-level railroad tracks on what was then known as "Death Avenue".

In the early 20th century, the Hudson barrier was surmounted by tunneling for passenger rail—and with the construction of the Holland Tunnel in 1927, the George Washington Bridge in 1931, and the Lincoln Tunnel in 1937—by creating fixed crossings for automobiles and trucks as well. Trucks could deliver freight anywhere in the city without requiring a railroad siding. The rail tunnels required electric propulsion, limiting their use for freight. A rail freight tunnel from Staten Island to Brooklyn was proposed, but never completed.

Rail freight traffic east of the Hudson that did not cross by barge had to go north some distance to cross the river by bridge. The first rail crossing of the Hudson was the Poughkeepsie Bridge built in 1888. The New York Central crossed just south of Albany, New York, where it continued west paralleling the Erie Canal to create the Water Level Route which competed with the Pennsylvania Railroad's more direct route that had to cross the Allegany Mountains. Even though the Poughkeepsie Bridge was closer to the city, it was less used.

Post-World War II

[edit]

The peak of rail freight came during World War II, when New York industries, including the Brooklyn Navy Yard, worked around the clock to support the war effort. After the war, the Interstate Highway System was built, along with many inland waterways, both competing with the railroads. The rail industry went through widespread consolidations and bankruptcies. Containerization revolutionized shipping. The Port Authority developed the Port Newark-Elizabeth Marine Terminal on Newark Bay. Piers in Brooklyin and Manhattan declined in usage and were abandoned. The 1980 Staggers Rail Act largely deregulated the U.S. railroads. The railroads de-emphasized "retail" railroading—movement of one or a few rail cars from a shipper's siding to a destination siding—in favor of long unit trains for bulk commodities, such as coal and ore. General cargo shifted to intermodal movement, first trailers on flat cars (TOFC), intermodal containers on flat cars (COFC), and then double-stacked containers, loaded on special well cars. Much manufacturing shifted to Asia, particularly Japan and China, leading to a sharp increase in international container movements.

Industry developed highly efficient logistics based on strategically located distribution centers, often serving an entire metropolitan area with a single center. Goods in long distance containers, whether shipped by rail or sea, typically must be unpacked at a distribution center outside the city before being sent to an end destination, such as a retail store.[2]

Heavy industry migrated out of the city. The Navy Yard closed in 1966. The Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge across the mouth of the harbor opened in 1964, allowing truck traffic to bypass Manhattan on the way to Long Island. The New York Central Railroad merged with the Pennsylvania Railroad to form the Penn Central in 1968, which then went bankrupt in 1970.[3] The Poughkeepsie Bridge was closed after a fire in 1974 and has since been converted to a pedestrian and bicycle path. The 60th Street Yard in Manhattan was sold and redeveloped as the Riverside South apartment complex, while the 30th Street Yard was converted into the West Side Yard storage facility for Long Island Rail Road trains. The West Side Line was last used for freight in 1982 and then converted to passenger use as Amtrak's Empire Connection in 1991, with the portion south of Penn Station abandoned and later converted into the High Line, an elevated pedestrian park.

The numerous car float operations across New York Harbor shrank to a single cross harbor barge line, the New York Cross Harbor Railroad. It merged with a trucking company, then ran into financial difficulties and sold its cross harbor operation to New York New Jersey Rail, LLC, which was subsequently purchased by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.

Attempts to revive rail freight in the City and Long Island

[edit]

Starting in the late 20th century, government officials have sought to increase the amount of freight to New York City and Long island that arrives by rail. To this end, several private and public sector initiatives have been undertaken:

- Construction of the Hunts Point Market in 1962, with extensive rail facilities connected to the Oak Point Yard

- The State of New York's $375 million "Full Freight Access Program" to allow cars with higher, TOFC clearance (but not double-stack) to reach Queens and Long Island, including construction of the Oak Point Link and the Harlem River Intermodal Yard in the Bronx. The link opened in 1998.[2] The Harlem River Intermodal Yard was intended to handle intermodal containers but none were ever lifted there.[2]: 21 Instead, it is being used for loading containerized trash onto trains for remote disposal.

- The restoration in 2006 of freight rail service to Staten Island via the Arthur Kill Vertical Lift Bridge at a cost of $72 million.

- The ExpressRail System, a $600 million investment in improved intermodal rail facilities at the container terminals on the west side of the Upper New York Bay and Newark Bay in New Jersey, and on Staten Island.[5] The last yard of the project, next to Greenville yard, opened on January 7, 2019.[6]

- The grant of a concession in 1997 to a private short haul railroad, the New York and Atlantic Railway, to handle all rail freight on the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR)'s rights-of-way.

- The rebuilding of the 65th Street Yard, a rail yard at the Brooklyn shore with two car float bridges that allow rail cars to be loaded and unloaded onto barges, by the City and State in 1999 at a cost of $20 million.[7] The car float bridges remained unused until 2012 because of financial disputes between the city and NYCHRR, which used bridges at the former Bush Terminal at 50th Street, instead. The 65th Street Yard was restored by the Port Authority for use by New York and New Jersey Rail, which it acquired in 2008.[8][9]

- The use of $4.8 million of American Recovery and Reinvestment Act funds to rehabilitate an NY&A rail spur at Enterprise Park at Calverton (EPCAL), an industrial park located at Calverton, Long Island.

- The acquisition of the New York and New Jersey Rail cross harbor car float operations by the Port Authority in 2008 for $16 million. The Port Authority then acquired the New Jersey Greenville Yard in 2010 and awarded a contract for its reconstruction as a rail to barge facility in 2011. The authority's board authorized $118.1 million for the overall project.[10] The State of New Jersey has budgeted $89 million in its 2012 budget to bring the Greenville Yard and Lift Bridge to a State-of-Good-Repair.[11]

- The opening, in September 2011, of Brookhaven Rail Terminal (BRT), a privately financed $40 million, 28-acre transload facility. It is projected to take 40,000 trucks off Long Island roads and transfer 1 million tons of freight a year by 2016.[12] The terminal includes three tracks for construction material, such as lumber, asphalt and concrete, and six tracks for merchandise, such as flour and biodiesel.[13] Plans to expand the yard have generated community opposition.[14]

- Rehabilitation and reactivation of the South Brooklyn Marine Terminal (SBMT) along the Bay Ridge Channel in Sunset Park in late 2012. The terminal includes a 77-acre roll on/roll off automobile import and processing facility at the 39th Street pier, and an 11-acre, recycling facility for the city's plastic, metal and glass waste stream at the 30th Street pier. Both facilities are served by newly built rail connections to the 65th Street yard.[15]

- Construction in 2014 of a transload facility for vegetable oil, food products and construction material at NYA's Wheel Spur Yard along Newtown Creek near Long Island City. NYA expects the facility to support replacement of the nearby Kosciuszko Bridge. The NYA also received permission from the LIRR, which owns most of the tracks on which NYA operates, to handle cars weighing up to 286,000 pounds (130 t), the top load limit for railroads in the eastern U.S. The previous LIRR limit was 263,000 pounds (119 t).[16]

- New York City's 2006 municipal solid waste plan. Under the plan, most of the city's non-recyclable solid waste is placed in intermodal containers and transported by rail to disposal sites. Some of the containers are loaded onto rail cars in the city, while others are first moved across New York Harbor by barge to transfer stations in Staten Island and New Jersey.[4]

Status

[edit]Routes

[edit]As of late 2013, most rail freight to New York City moves over lines on the west side of the Hudson and is unloaded in New Jersey, where it is brought by truck to the city. Railroad freight cars that enter the city or Long Island do so via the Bronx, Brooklyn, or Staten Island.[17]

The Bronx

[edit]The main mainland rail connection to New York City and Long Island from the national rail network is via tracks on the east bank of the Hudson. CSX Transportation freight trains from the west cross the Hudson on the Alfred H. Smith Memorial Bridge, 140 miles (230 km) to the north at Selkirk. From there to Poughkeepsie the two-track line, known as the Hudson Subdivision, is owned by CSX but is leased to Amtrak.[17] Amtrak runs 28 trains a day on this segment. South of Poughkeepsie, the Hudson Line widens, first to three and then four tracks, becomes electrified with third rail. This section is owned by Metro North Commuter Railroad.[18] CSX runs four road freight trains a day on this line with an average of 75 cars per train, the equivalent of 900 trucks.[19]

Just north of the Spuyten Duyvil Bridge in the Bronx, the Hudson Line connects with the Oak Point Link, which acts as a replacement for the decommissioned Port Morris Freight Branch in addition to connecting the Harlem River Intermodal Yard and the Oak Point Yard. The Oak Point Yard, the largest rail yard in New York City, directly serves local industry and the Hunts Point Market and also connects to Amtrak's Northeast Corridor line to Boston, which is used by the Providence and Worcester Railroad to haul crushed stone to Long Island. Freight trains to Long Island move from the yard over the Hell Gate Bridge to the New York and Atlantic yard at Fresh Pond Junction in Queens. As part of the deal to create the Oak Point Link, the Canadian Pacific Railway was granted trackage rights over the Hudson Line and the link, but Canadian Pacific currently allows CSX to haul its traffic in exchange for hauling CSX traffic on another route.

Since 1997, the New York and Atlantic, a short-line railroad, has had the concession to provide freight service over the tracks of the MTA's Long Island Rail Road, the largest commuter operation in North America. The NY&A carries about 20,000 carloads a year, including lumber, paper, building materials, plastic, aggregates, food products, and recyclables, over 269 route miles. As of 2011, it has seven transload facilities, in Brooklyn, Queens, Farmingdale, Hicksville and Yaphank.[20] Clearances along the LIRR prohibit double-stack operations.

Brooklyn

[edit]

The sole remaining car float operation in the area, New York New Jersey Rail, carries railroad cars from the Greenville Yard in Jersey City to Brooklyn, where cars either go to local customers or are picked up by the New York and Atlantic and moved over the Bay Ridge Branch to Fresh Pond Junction.[17] In 2004, when it was still run by a public company, New York Regional Rail, it carried 3400 carloads (a carload being one loaded rail car), charging between $250 and $1,500 per carload, and estimated that it needed to handle in excess of 4200 carloads per year to be profitable.[21] The operation, now run by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, began using the 65th Street Yard in Brooklyn in July 2012 and hopes to increase annual traffic from 1600 carloads to 23,000 by 2017.[19][22] On September 17, 2014, the Port Authority announced that it was funding a major redevelopment of the Greenville Yard, to include a new container terminal, two new rail to barge transfer bridges, two new car float barges, each with 18 rail car capacity, and three new KLW SE10B ultra low emission locomotives.[23] In November 2017, the first of the new barges was delivered.[24] The second was delivered in December 2018.

Staten Island

[edit]Staten Island has a short, direct connection to the national rail network. Trains enter from New Jersey by way of the Arthur Kill Vertical Lift Bridge,[17] which was reopened in 2006.[25] They serve the Staten Island Transfer Station at Fresh Kills Landfill, which handles municipal solid waste for the borough, and the refurbished, 187-acre (76 ha) Howland Hook Marine Terminal. The latter has a new intermodal rail yard and can handle 425,000 containers a year. It is part of the Port Authority's ExpressRail system and is served by the Staten Island Railroad with a connection via Conrail Shared Assets Operations Chemical Coast to both CSX and Norfolk Southern.[5]

Rail share of freight

[edit]Measured by ton-miles, about 40% of freight in the United States is moved by rail.[26] However, there are significant regional variations. In the west, 65% of freight moves by rail, while in the north-east only 19% moves by rail.[2]p. 14 Much of U.S. railroad freight consists of heavy commodities that are not significant in the New York economy, for example coal is 44% of total national rail tonnage. Intermodal tonnage is only about 8.9%.[27] In addition to highway and rail, cargo arrives in New York City by air, barge and, of course, ship, the port being the largest on the East Coast of North America. A major source of freight leaving the city is trash. The closing of the Fresh Kills Landfill in 2001 forced the city to transport its waste material to distant sites. New York City's Solid Waste Management Plan[28] calls for each borough to ship its own trash, the Bronx and Staten Island using rail directly and the rest of the city using barge to rail.

The Panama Canal expansion project, which opened in 2016, was expected to bring more container traffic from Asia directly to the Port of New York, instead of coming via the railroad "Land bridge" from U.S. West Coast ports. The Port Authority has spent over $1 billion to raise the deck of the Bayonne Bridge to allow the larger New Panamax ships that now use the expanded canal to reach its existing container terminals in New Jersey, and has spent $235 million to buy a 130 acres (53 ha) portion of the former Military Ocean Terminal at Bayonne, which is not obstructed by the Bayonne Bridge.

Proposals to increase freight rail use

[edit]

A number of proposals have been put forward to increase the share of rail freight movement within the City and Long Island:

- Construction of an intermodal rail-to-truck yard at a 100-acre (40 ha) site in the West Maspeth section of Queens. The location is near the intersection of Interstate 278 and Interstate 495. The project has received intense opposition for neighbors concerned about increased truck traffic on local streets that lead to the highway interchange. A City University of New York (CUNY) study pointed out that "no current demand for a containerized truck-rail facility has yet been demonstrated" in part because intermodal containers generally must be unloaded at major distribution centers, few of which are located on Long Island.[2]: 22 The study also noted that standard double stack rail equipment is too wide to run on tracks where third rail is used, as it is on much of the Long Island Rail Road's passenger routes.

- Construction of a transload facility at the former Pilgrim State Hospital. This project has also been stymied by local opposition, though Governor Paterson vetoed a 2008 bill that would have killed the project by incorporating the site into a nearby state park. The same CUNY study, commissioned by the state after the veto, concluded that "there is an immediate demand for bulk service"—rail-shipped commodities such as building materials, plastics, paper, and food—that was unmet due to a lack of transloading facilities on Long Island. It identified 12 additional candidate sites besides Pilgrim State, including the Brookhaven Rail Terminal that has since opened.[2]: 3, 5, 8, 16

- Rebuilding parts of the Hunts Point Cooperative Market in the Bronx, already a major rail freight destination, to facilitate greater rail use. The market received a $10 million grant in 2012 for this purpose.[29]

- Construction of a double-stack-ready Cross Harbor Rail Tunnel from Greenville, New Jersey to Brooklyn, at a cost estimated in 2004 at between $4.8 and $7.4 billion, depending on whether one or two tracks are provided.[30] The Port Authority is preparing a new environmental impact statement for the project,[30] which has come under criticism because of its high cost (all the US freight railroads combined spent $10.7 billion on capital expenditures in 2010[31]), modest projected impact on overall truck traffic (around a 5% reduction) and potential impact on local communities, such as West Maspeth.

- Building a new container port on Brooklyn's Sunset Park waterfront with a rail link to the proposed tunnel. Brooklyn currently has a container operation at Red Hook, but it has no rail connection. (Sea access to Brooklyn is not obstructed by the Bayonne Bridge.)

A proposal would use right-of-way that now carries freight, including the Bay Ridge Branch, to build a new Triboro RX passenger service connecting the Bronx, Queens and Brooklyn, potentially limiting use for rail freight.[32][33]

Freight NYC

[edit]In July 2018, the New York City Economic Development Corporation announced a $100 million plan called Freight NYC to improve the flow of freight into and out of New York City.[34][35] The plan's rail component includes:

- Constructing up to four new transload facilities in Brooklyn and Queens[34][35]

- Constructing more passing sidings[34][35]

- Supporting the Port Authority's Cross Harbor Freight Program (CHFP)[35]

- Supporting the Metropolitan Rail Freight Council (MRFC) Action Plan aimed at increasing rail freight service to locations east of the Hudson[35]

The Freight NYC plan also includes a marine component that would build more barge terminals and an effort to support greener trucking.

Impact of electronic commerce

[edit]The rise of electronic commerce, coupled with faster delivery services such as Amazon Prime, has increased truck traffic throughout the area and has led to demand for more warehouse space within the city.[36] At least some of these warehouses are being located near rail terminals, including Amazon's Staten Island facility which is a short distance form the Howland Hook Marine Terminal and Arlington Yard.

Active freight rail yards in New York City and Long Island

[edit]Active freight rail yards in New York City and Long Island include:[17]

- 51st Street Yard - Brooklyn shore, used by NYNJ Rail[37]

- 65th Street Yard – Brooklyn shore, reopened in 2012 after being refurbished for cross harbor car float barge, which connects to Greenville Yard in New Jersey. Hub for NYNJ Rail.[37]

- Arlington Yard – Staten Island, used for Port Liberty NY Container Terminal operations & Conrail Shared Assets Operations (CSAO)[38][39]

- Brookhaven Rail Terminal – facility for bulk commodities, in eastern Long Island, hub of NY&A[40]

- Fresh Pond Junction – Queens, main freight yard on Long Island, hub of NY&A[40]

- Harlem River Intermodal Yard – the Bronx, intended for intermodal container traffic, used for trash containers instead

- Hunts Point Terminal Market – the Bronx, largest food distribution center in New York, hub for CSX[39]

- Oak Point Yard – Bronx, largest freight yard in the city, owned by CSX[39]

- Pine Aire Yard – Farmingdale, owned by NY&A and used to serve industries along the LIRR Main Line.

- Port Liberty New York Container Terminal – Staten Island, includes an intermodal rail yard[38]

- Staten Island Transfer Station - contains a small railyard located by the formerly used Fresh Kills landfill where containerized trash from the New York City Department of Sanitation is transported by Conrail Shared Assets Operations (CSAO) via the Travis Branch rail line[41]

- South Brooklyn Marine Terminal – Brooklyn shore, connects to South Brooklyn Railway and NYNJ Rail[37]

- Wheel Spur Yard – Queens, reopened NY&A transload facility in Long Island City used for vegetable oil, food products and construction material.[42]40°44′19″N 73°56′53″W / 40.7385°N 73.948°W

The New York City Subway system has many other rail yards, but, with two exceptions, these are not connected with the national rail network. The two railroads with direct connections to the New York City Subway are the South Brooklyn Railway and the LIRR Bay Ridge Branch.

See also

[edit]- New York Connecting Railroad

- Rail transportation in the United States

- Timeline of Jersey City area railroads

- Transportation in New York City

- Vision 2020: New York City Comprehensive Waterfront Plan

References

[edit]- ^ McCahon, Mary E. & Johnston, Sandra G. (December 2003). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Route 1 Extension" (PDF). National Park Service. p. 3 (Item 8). Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g Paaswell, Robert E.; Eickemeyer, Penny (June 9, 2011). "NYSDOT Consideration of Potential Intermodal Sites for Long Island" (PDF). CUNY Institute for Urban Systems University Transportation Research Center. p. 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 17, 2011. Retrieved December 19, 2011.

- ^ Pinkston, Elizabeth (2003). "A Brief History of Amtrak." The Past and Future of U.S. Passenger Rail Service. (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Congressional Budget Office)

- ^ a b c "Appendix C - Rail Freight Capacity Analysis For Movement Of New York City Waste" (PDF). City of New York Department of Sanitation. June 2018.

- ^ a b "Port of New York and New Jersey - ExpressRail". panynj.gov.

- ^ Panynj Achieves Major Milestone in Efforts to Enhance Movement of Cargo by Rail Outside NY-NJ Region, Louanne Wong, Global Container Terminals, January 7, 2019

- ^ Operator Sought for Rebuilt Brooklyn Rail Yard, New York Times, August 31, 2000, Joseph Freed

- ^ "Bay Ridge LIRR". trainsarefun.com.

- ^ "South Brooklyn Railway". Members.trainweb.com. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- ^ "Port Authority Board Approves Purchase and Redevelopment of Greenville Yards" (Press release). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. May 18, 2010. Archived from the original on December 27, 2010. Retrieved December 25, 2011.

- ^ FY 2012 Transportation Capital Program, New Jersey Department of Transportation

- ^ Grand Opening of Brookhaven Freight Train Terminal Archived April 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Carolyn Fortino, September 27, 2011

- ^ "Yaphank freight terminal opens". Newsday.com. September 27, 2011. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- ^ "Court bars Brookhaven Rail Terminal sand mining". Newsday.

- ^ "South Brooklyn Marine Terminal". NYCEDC.

- ^ "NY&A gets OK to haul 286,000-lb. rail cards; Wheel Spur yard change" (PDF). Apex. No. 2. Anacostia Rail Holdings. Spring 2014. p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e "Railroads in New York - 2016" (PDF). New York State Department of Transportation. January 2016. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ^ "Amtrak leases Empire Corridor from CSX - RailwayAge Magazine". Railwayage.com. October 18, 2011. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- ^ a b Hu, Winnie (July 20, 2012). "Rail Yard Reopens as City's Freight Trains Rumble into Wider Use". The New York Times.

- ^ "Anacostia & Pacific Company, Inc | New York & Atlantic Railway". Anacostia.com. December 22, 2011. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- ^ "New York Regional Rail Cp NYRR description of business". Hotstocked.com. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- ^ "NJTPA Freight Committee, October 2012" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 4, 2013. Retrieved November 8, 2012.

- ^ Port Authority Board Approves Major Redevelopment Of Greenville Yard To Improve Cargo Movement In The Port Archived February 22, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Port Authority Press Release Number 190-2014, September 17, 2014

- ^ Moore, Kirk (November 10, 2017). "Metal Trades delivers New York rail float barge". WorkBoat. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ^ Young, Deborah (October 5, 2006). "Riding the rails into the port's future". Staten Island Advance.

- ^ "Overview of America's Freight Railroads" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 5, 2003. Retrieved December 25, 2011.

- ^ "Error". aar.org.

- ^ Final Comprehensive Solid Waste Management Plan Executive Summary Archived November 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Hunts Point Produce Market Offered $10 Million Grant". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on June 23, 2012.

- ^ a b "Cross Harbor Freight Program - Studies & Reports - The Port Authority of NY & NJ". Panynj.gov. September 11, 2001. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- ^ "Error". aar.org.

- ^ "How About A Subway Linking Brooklyn, Queens & The Bronx WITHOUT Manhattan?". Gothamist. August 22, 2013. Archived from the original on August 21, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- ^ "Overlooked Boroughs Where New York City's Transit Falls Short and How to Fix It Technical Report" (PDF). Regional Plan Association. February 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- ^ a b c Geiger, Daniel (July 16, 2018). "City reveals plan to invest $100M in freight infrastructure". Crain's New York Business. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "New York Works: De Blasio Administration Launches Freight NYC, A $100M Plan to Modernize New York City's Freight Distribution System". NYCEDC. July 16, 2018. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ Haag, Matthew; Hu, Winnie (October 27, 2019). "1.5 Million Packages a Day: The Internet Brings Chaos to N.Y. Streets". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c "New York New Jersey Rail, LLC". nynjr.com. Retrieved November 18, 2024.

- ^ a b "ExpressRail Information | Port Authority of New York and New Jersey". www.panynj.gov. Retrieved November 18, 2024.

- ^ a b c "CSX Operations in New York". CSX. June 3, 2016. Retrieved November 18, 2024.

- ^ a b "NYA – New York & Atlantic Railway". Anacostia Rail Holdings. Retrieved November 18, 2024.

- ^ "NYC.gov". December 23, 2007. Archived from the original on December 23, 2007. Retrieved November 18, 2024.

- ^ Wheelspur Rail Yard in LIC Back in Operation, Mitch Waxman, Brownstoner, April 16, 2015

Further reading

[edit]- Cambridge Systematics, Inc. (June 2013). NYMTC Regional Freight Plan Update 2015-2040 Interim Plan (PDF) (Report). New York Metropolitan Transportation Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 14, 2014.

- HDR Engineering (March 2013). Freight Rail Capacity and needs to Year 2040 (PDF) (Report). North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority.

- Miller, Benjamin (November 2005). "An Evaluation of New York's Full Freight Access Program and Harlem River Intermodal Rail Yard Project" (PDF). CUNY.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

External links

[edit]- Flickr New York Rail Marine group, with photos of marine and allied shore rail freight operations

- Industrial & Offline Terminal Railroads of Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island, Bronx & Manhattan at the Wayback Machine (archived January 25, 2020)