Queen Anne's Gate

"the best of their kind in London" | |

| Former name(s) | Queen Square, Park Street |

|---|---|

| Maintained by | Transport for London |

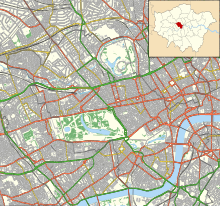

| Location | Central London, Westminster, London |

| Postal code | SW1 |

| Nearest Tube station | |

| Coordinates | 51°30′02″N 0°07′56″W / 51.5005°N 0.1322°W |

| East end | Storey's Gate |

| West end | Petty France |

Queen Anne’s Gate is a street in Westminster, London. Many of the buildings are Grade I listed, known for their Queen Anne architecture. Simon Bradley and Nikolaus Pevsner described the Gate’s early 18th century houses as “the best of their kind in London.” The street’s proximity to the Palace of Westminster made it a popular residential area for politicians; Lord Palmerston was born at No. 20 while Sir Edward Grey and Lord Haldane, senior members of H. H. Asquith’s Cabinet, were near neighbours at Nos. 3 and 28 respectively. Other prominent residents included the philosopher John Stuart Mill at No. 40, Mansfield Smith-Cumming, the founder of MI6 at No. 21, and Admiral “Jacky” Fisher at No. 16.

Location

[edit]Queen Anne’s Gate runs from Old Queen Street in the east to a cul-de-sac in the west. It runs parallel with Birdcage Walk to the north and Petty France, Broadway and Tothill Street to the south. Carteret Street joins Queen Anne’s Gate on its southern side.[1]

History

[edit]Queen Anne's Gate is formed from two older streets, Park Street, to the eastern end and part of the Christ's Hospital estate, and Queen Square, to the western end and developed by the South Sea Company.[2] Until 1873 the two were divided by a wall, with the Statue of Queen Anne (see below) set within it.[3] In 1874 the wall was demolished, Park Street and Queen Square were renumbered and the whole was renamed Queen Anne's Gate.[3]

These narrow houses, three or four storeys high - one for eating, one for sleeping, a third for company, a fourth underground for the kitchen, a fifth perhaps at the top for servants - give the idea of a cage with its sticks and birds

The street includes some "outstanding" examples of Queen Anne and Georgian townhouses.[3] The older buildings, many dating from the original laying-out of Queen Square in 1704-5, are found at the western end. The layout of the houses follows what Sir John Summerson called "the insistent verticality of the London house" [see box].[4] A particular feature of these buildings are their elaborate doorcases. Westminster City Council’s survey of the Birdcage Walk conservation area notes their intricate carving with “foliage and figureheads.”[5] Simon Bradley and Nikolaus Pevsner, in the 2003 revised London 6: Westminster in the Buildings of England series, consider the houses in Queen Anne's Gate “the best of their kind in London.”[6]

The statue of Queen Anne dates from the time of the queen. Carved from Portland stone, its sculptor is not known. The statue has a Grade I listing.[7] There was a chapel at 50 Queen Anne's Gate, built in 1706 as a private chapel to serve the residents of Queen Square. By 1870, it had become a charitable school, and later served as a mission hall and a police institute. By 1890, it had become offices.[8] The site is now occupied by the modern Ministry of Justice building.[a]

Originally built as houses, by the later 20th century many of the buildings in Queen Anne’s Gate had been converted to offices. The 21st century has seen a reversal of this trend, with buildings being reconverted to private residences.[9][10][11][b]

Buildings, occupants and listing designations

[edit]Queen Anne’s Gate has been home to a number of notable people, including a quantity of politicians given its proximity to the Palace of Westminster. Some of the houses have Blue plaques commemorating their residents.[13] Many of the buildings are listed, most at the highest grade, Grade I, sometimes for their architectural merit and sometimes for their historical significance.

- No. 2 is of c. 1825 and is listed at Grade II.[14]

- No. 3 dates from the 1770s, although it was entirely rebuilt behind the existing facade in the early 21st century. Home of Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon, Foreign Secretary at the outbreak of the First World War, and earlier of the politicians James Harris, 5th Earl of Malmesbury and Edward Knatchbull-Hugessen, 1st Baron Brabourne.[15] Nos. 1-3 are listed Grade II.[16]

- Nos. 5-13 are listed at Grade I.[17]

- Nos. 6-12 are listed at Grade II*. Of the mid-19th century, the block was designed by the Elmes, father and son.[18] Howard Colvin notes that No. 6 was designed for the Parliamentary Agency Offices.[19]

- Nos. 9-13, the basement of this block housed a private pub, The Bride of Denmark, established by staff at the Architectural Review which had offices at No. 9 above. The pub was fitted out with architectural salvage from London public houses destroyed in the Second World War and was itself demolished in the 1990s, following Robert Maxwell’s acquisition of the Review.[20][c]

- No. 14 was home of the antiquarian Charles Townley[22] and later served as the office of the architectural practice T. P. O’Sullivan & Partners. Nos. 14-22, 22a and 24 are listed Grade I.[23] No. 14 was designed by Samuel Wyatt and he may have been involved elsewhere in the street.[24][d]

- No. 15 is listed Grade I.[28] It contains interiors by Edwin Lutyens, undertaken for his friend and supporter Edward Hudson.[6][e]

- No. 16, home of John Fisher, 1st Baron Fisher, Admiral of the fleet and naval moderniser; and of the abolitionist William Smith; where there are commemorative blue plaques in both names.[30] The restoration of the house won a Georgian Group award. It is now owned by the businessman Troels Holch Povlsen.[31]

- No. 17 is listed Grade I. Dating from the very early 18th century, the house, with its companion No. 19, form among the best remaining elements of the original Queen Anne design of the street.[32] Edwin Lutyens, who also undertook work elsewhere in the street, lived there in the mid-1920s.[33]

- No. 19 was, between 1705 and 1718, in the 1920s, home to William Paterson, a founder of the Bank of England. In the 1920s, Sir Aston Webb, an architect who undertook the refacing of Buckingham Palace in 1913, lived at the house.[34]

- No. 20 was the birthplace of Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston.[35] In the 1920s, it was home to George Riddell, 1st Baron Riddell, owner of the News of the World and confidant of David Lloyd George.[36]

- No. 21, a house dating to 1704 that at one time was the home of Sir Mansfield Smith-Cumming, the founder of MI6. Its initial operations were based at No. 21. Reputedly, a tunnel led from it to MI6's headquarters at 54 Broadway nearby.[37] Nos. 21 and 23 are listed Grade I.[38]

- No. 24, home to the politician Sir George Shuckburgh-Evelyn from 1783 to 1788, and the judge Sir Edward Vaughan Williams, from 1836 until his death in 1875.[39]

- No. 25 is listed Grade I.[40]

- No. 26 was home to Sting and Trudie Styler for approximately 20 years until 2016 when they sold the home and art collection.[41] Nos. 26-32 inclusive are listed at Grade I.[42]

- No. 28, in the early 20th century, No. 28 was the home of Richard Haldane, 1st Viscount Haldane, army reformer as Secretary of State for War, and Lord Chancellor,[f][44] and subsequently of Ronald and Nancy Tree (later Lancaster).[6]

- No. 32, in the early 1920s this house was the home of the writer Elizabeth Bowen who resided there with her great aunt Edith (Lady Allendale).[45]

- No. 34, formerly the home of Edward Tennant, 1st Baron Glenconner, and from 1962 to 2013, home to St Stephen's Club, a private member's club.[46] No. 34 was designed by Detmar Blow and is listed Grade II.[47]

- No. 40 was home to John Stuart Mill and his father James Mill.[48] It is Grade I listed.[49]

- Nos. 42, 44 and 46 are also all Grade I listed buildings.[50][51][52] No.s 40, 42 and 44 were the headquarters of the National Trust from 1945-1982.[53]

Old Queen Street

[edit]Old Queen Street is a continuation of Queen Anne’s Gate, connecting it to Storey’s Gate. It was first laid out with townhouses in the late 18th century. Seven of the buildings on the street are listed, all at Grade II: Nos. 9 & 11,[54] No. 20,[55] No. 24,[56] Nos. 26 & 28,[57] Nos. 30 & 32,[58] No. 34[59] and No. 43.[60]

Gallery

[edit]-

1-3 Queen Anne’s Gate

-

6-12 Queen Anne’s Gate

-

14 Queen Anne's Gate

-

15 Queen Anne’s Gate

-

Doorcase at No. 28 Queen Anne's Gate

-

40 Queen Anne's Gate

-

Statue of Queen Anne at Queen Anne's Gate London

-

11 Old Queen Street

Notes

[edit]- ^ Now 102 Petty France, the present building was known on its completion in 1976 as 50 Queen Anne’s Gate. It replaced a Victorian mansion block, Queen Anne’s Mansions, a building described by Nikolaus Pevsner as an “indescribable horror”.

- ^ In 2022, the Halifax recorded Queen Anne’s Gate as the fifth most expensive residential street in Britain with an average house price of £17.5M.[12]

- ^ Nikolaus Pevsner was a member of the Architectural Review’s board and regularly attended its meetings every Wednesday at 9 Queen Anne’s Gate. While on the board he wrote an influential series of essays on architectural history for the journal.[21]

- ^ Neither Howard Colvin, in his Biographical Dictionary of British Architects 1600-1840,[25] or John Martin Robinson, in his unpublished thesis, Samuel Wyatt: Architect,[26] both published in the late-1970s, record Wyatt's role in the design of No. 14. However, later research has confirmed it. In his paper for the Georgian Group, Dan Cruickshank discusses Wyatt’s designs for the house, and his possible wider involvement in others on the street.[27]

- ^ In television, it was home to the fictional Persuader, Lord Brett Sinclair, (Roger Moore), and can be seen in some episodes, with Sinclair's Aston Martin DBS parked outside.[29]

- ^ In 1911 Haldane had entertained the German Kaiser to lunch at No. 28, an occasion that was subsequently held against him at the height of anti-German feeling during World War I.[43]

References

[edit]- ^ Westminster City Council 2008, p. 9.

- ^ Cruickshank 1992, pp. 56–57.

- ^ a b c Bradley & Pevsner 2003, p. 712.

- ^ a b Summerson 1978, p. 67.

- ^ Westminster City Council 2008, p. 31.

- ^ a b c Bradley & Pevsner 2003, p. 713.

- ^ Historic England. "Statue of Queen Anne against north flank of No.15 Queen Anne's Gate (Grade I) (1227294)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Cox 1926, pp. 137–141.

- ^ Wilson, Rob (28 July 2020). "Reworking of 12 Queen Anne's Gate plots as apartments". Architects’ Journal. Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ "Restoration of Grade I listed house, Queen Anne's Gate". Adam Architecture. Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Churchill, Penny (14 February 2015). "Westminster properties for sale". Country Life. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ "Queen Anne's Gate crowned most expensive 'Royal Jubilee' street" (PDF). The Halifax. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 December 2022. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Westminster City Council 2008, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Historic England. "2, Queen Anne's Gate (Grade II) (1227297)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ "Edward Grey blue plaque". Open Plaques. Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "1-3 Queen Anne's Gate (Grade II) (1227240)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "5-13, Queen Anne's Gate (Grade I) (1227241)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "6-11, Queen Anne's Gate (Grade II*) (1265413)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Colvin 1978, p. 292.

- ^ "The Bride of Denmark's Lion Bar". Architectural Review. 14 April 2015. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Harries 2011, p. 437.

- ^ "Charles Townley blue plaque". Open Plaques. Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "14-22, 22a & 24 Queen Anne's Gate (Grade I) (1227298)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Bradley & Pevsner 2003, p. 714.

- ^ Colvin 1978, p. 958.

- ^ Robinson 1973, pp. 422–435.

- ^ Cruickshank 1992, pp. 59–61.

- ^ Historic England. "15 Queen Anne's Gate (Grade I) (1265463)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ "Lord Sinclair's London residence". James Bond locations. 8 November 2014. Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ "John Fisher blue plaque". Open Plaques. Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ "Povlsen, Troels Holch". Companies House. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "17 & 19, Queen Anne's Gate (Grade I) (1227295)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ "No. 17 Queen Anne's Gate". Survey of London. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ^ "No. 19 Queen Anne's Gate". Survey of London. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ^ "Henry John Temple blue plaque". Open Plaques. Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ "No. 20 Queen Anne's Gate". Survey of London. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ^ Martin, Guy (30 November 2013). "The Spy Who Lived Here: Own the Real-Life M's London Mansion--For $22 Million". Forbes. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "21 & 23, Queen Anne's Gate (Grade I) (1227296)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ "No. 24 Queen Anne's Gate". BHO. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ Historic England. "25, Queen Anne's Gate (Grade I) (1265450)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ "Sting and Trudy Styler The Composition of a Collection". Christies. 16 February 2016. Archived from the original on 4 May 2022. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "26-32, Queen Anne's Gate (Grade I) (1227299)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Grigg 2003, p. 427.

- ^ "Lord Haldane, No. 26". Historic England. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Glendinning 1977, p. 44.

- ^ "St Stephen's Club to close". PoliticsHome. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ Historic England. "34, Queen Anne's Gate (Grade II) (1265414)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ "John Stuart Mill and James Mill blue plaque". Open Plaques. Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "40, Queen Anne's Gate (Grade I) (1227300)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "42, Queen Anne's Gate (Grade I) (1227328)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "44, Queen Anne's Gate (Grade I) (1227329)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "46, Queen Anne's Gate (Grade I) (1265430)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ "No. 42 Queen Anne's Gate Heritage Record". National Trust. Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "9 & 11 Old Queen Street (Grade II) (1266277)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "20 Old Queen Street (1225626)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "24 Old Queen Street (Grade II) (1266275)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "26 & 28 Old Queen Street (Grade II) (1225627)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "30 & 32 Old Queen Street (Grade II) (1266276)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "34 Old Queen Street (Grade II) (1225628)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "43 Old Queen Street (Grade II) (1225630)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

Sources

[edit]- Bradley, Simon; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2003). London: Westminster. The Buildings of England. New Haven, US, London, UK: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300095951. OCLC 609428632.

- Colvin, Howard (1978). A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects: 1600-1840. London: John Murray. OCLC 1337285841.

- Cox, Montagu H (1926). "Queen Anne's Gate". Survey of London. Vol. 10. St Margaret, Westminster. pp. 137–141.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Cruickshank, Dan (1992). "Queen Anne's Gate" (PDF). The Georgian Group Journal. II: 56–67.

- Glendinning, Victoria (1977). Elizabeth Bowen: Portrait of a Writer. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 9780297773696.

- Grigg, John (2003). Lloyd George: War Leader, 1916–1918. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-140-28427-0.

- Harries, Susie (2011). Nikolaus Pevsner – The Life. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 9780701168391.

- Robinson, John Martin (October 1973). Samuel Wyatt, Architect (DPhil). Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- Summerson, John (1978). Georgian London. London: Barrie & Jenkins. OCLC 922574924.

- Westminster City Council, ed. (2008). Birdcage Walk Conservation Area (PDF).