Pyxis

| Constellation | |

| |

| Abbreviation | Pyx |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Pyxidis |

| Pronunciation | /ˈpɪksɪs/, genitive /ˈpɪksɪdɪs/ |

| Symbolism | The compass box |

| Right ascension | 9h |

| Declination | −30° |

| Quadrant | SQ2 |

| Area | 221 sq. deg. (65th) |

| Main stars | 3 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 10 |

| Stars with planets | 3 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 0 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 1 |

| Brightest star | α Pyx (3.68m) |

| Messier objects | 0 |

| Bordering constellations | Hydra Puppis Vela Antlia |

| Visible at latitudes between +50° and −90°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of March. | |

Pyxis[a] is a small and faint constellation in the southern sky. Abbreviated from Pyxis Nautica, its name is Latin for a mariner's compass (contrasting with Circinus, which represents a draftsman's compasses). Pyxis was introduced by Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille in the 18th century, and is counted among the 88 modern constellations.

The plane of the Milky Way passes through Pyxis. A faint constellation, its three brightest stars—Alpha, Beta and Gamma Pyxidis—are in a rough line. At magnitude 3.68, Alpha is the constellation's brightest star. It is a blue-white star approximately 880 light-years (270 parsecs) distant and around 22,000 times as luminous as the Sun.

Pyxis is located close to the stars that formed the old constellation Argo Navis, the ship of Jason and the Argonauts. Parts of Argo Navis were the Carina (the keel or hull), the Puppis (the stern), and the Vela (the sails). These eventually became their own constellations. In the 19th century, John Herschel suggested renaming Pyxis to Malus (meaning the mast) but the suggestion was not followed.

T Pyxidis, located about 4 degrees northeast of Alpha Pyxidis, is a recurrent nova that has flared up to magnitude 7 every few decades. Also, three star systems in Pyxis have confirmed exoplanets. The Pyxis globular cluster is situated about 130,000 light-years away in the galactic halo. This region was not thought to contain globular clusters. The possibility has been raised that this object might have escaped from the Large Magellanic Cloud.[3]

History

[edit]

In ancient Chinese astronomy, Alpha, Beta, and Gamma Pyxidis formed part of Tianmiao, a celestial temple honouring the ancestors of the emperor, along with stars from neighbouring Antlia.[4]

The French astronomer Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille first described the constellation in French as la Boussole (the Marine Compass) in 1752,[5][6] after he had observed and catalogued almost 10,000 southern stars during a two-year stay at the Cape of Good Hope. He devised fourteen new constellations in uncharted regions of the Southern Celestial Hemisphere not visible from Europe. All but one honoured instruments that symbolised the Age of Enlightenment.[b] Lacaille Latinised the name to Pixis [sic] Nautica on his 1763 chart.[7] The Ancient Greeks identified the four main stars of Pyxis as the mast of the mythological Jason's ship, Argo Navis.[8]

German astronomer Johann Bode defined the constellation Lochium Funis, the Log and Line—a nautical device once used for measuring speed and distance travelled at sea—around Pyxis in his 1801 star atlas, but the depiction did not survive.[9] In 1844 John Herschel attempted to resurrect the classical configuration of Argo Navis by renaming it Malus the Mast, a suggestion followed by Francis Baily, but Benjamin Gould restored Lacaille's nomenclature.[7] For instance, Alpha Pyxidis is referenced as α Mali in an old catalog of the United States Naval Observatory (star 3766, page 97).[10]

Characteristics

[edit]

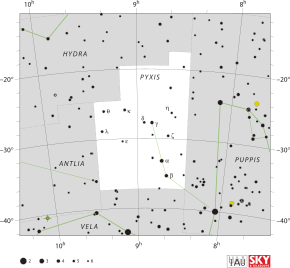

Covering 220.8 square degrees and hence 0.535% of the sky, Pyxis ranks 65th of the 88 modern constellations by area.[11] Its position in the Southern Celestial Hemisphere means that the whole constellation is visible to observers south of 52°N.[11][c] It is most visible in the evening sky in February and March.[12] A small constellation, it is bordered by Hydra to the north, Puppis to the west, Vela to the south, and Antlia to the east. The three-letter abbreviation for the constellation, as adopted by the International Astronomical Union in 1922, is "Pyx".[13] The official constellation boundaries, as set by Belgian astronomer Eugène Delporte in 1930, are defined by a polygon of eight sides (illustrated in infobox). In the equatorial coordinate system, the right ascension coordinates of these borders lie between 8h 27.7m and 9h 27.6m , while the declination coordinates are between −17.41° and −37.29°.[14]

Features

[edit]Stars

[edit]

Lacaille gave Bayer designations to ten stars now named Alpha to Lambda Pyxidis, skipping the Greek letters iota and kappa. Although a nautical element, the constellation was not an integral part of the old Argo Navis and hence did not share in the original Bayer designations of that constellation, which were split between Carina, Vela and Puppis.[7] Pyxis is a faint constellation, its three brightest stars—Alpha, Beta and Gamma Pyxidis—forming a rough line.[15] Overall, there are 41 stars within the constellation's borders with apparent magnitudes brighter than or equal to 6.5.[d][11]

With an apparent magnitude of 3.68, Alpha Pyxidis is the brightest star in the constellation.[17] Located 880 ± 30 light-years distant from Earth,[18] it is a blue-white giant star of spectral type B1.5III that is around 22,000 times as luminous as the Sun and has 9.4 ± 0.7 times its diameter. It began life with a mass 12.1 ± 0.6 times that of the Sun, almost 15 million years ago.[19] Its light is dimmed by 30% due to interstellar dust, so would have a brighter magnitude of 3.31 if not for this.[17] The second brightest star at magnitude 3.97 is Beta Pyxidis, a yellow bright giant or supergiant of spectral type G7Ib-II that is around 435 times as luminous as the Sun,[20] lying 420 ± 10 light-years distant away from Earth.[18] It has a companion star of magnitude 12.5 separated by 9 arcseconds.[21] Gamma Pyxidis is a star of magnitude 4.02 that lies 207 ± 2 light-years distant.[18] It is an orange giant of spectral type K3III that has cooled and swollen to 3.7 times the diameter of the Sun after exhausting its core hydrogen.[22]

Kappa Pyxidis was catalogued but not given a Bayer designation by Lacaille, but Gould felt the star was bright enough to warrant a letter.[7] Kappa has a magnitude of 4.62 and is 560 ± 50 light-years distant.[18] An orange giant of spectral type K4/K5III,[23] Kappa has a luminosity approximately 965 times that of the Sun.[20] It is separated by 2.1 arcseconds from a magnitude 10 star.[24] Theta Pyxidis is a red giant of spectral type M1III and semi-regular variable with two measured periods of 13 and 98.3 days, and an average magnitude of 4.71,[25] and is 500 ± 30 light-years distant from Earth.[18] It has expanded to approximately 54 times the diameter of the Sun.[22]

Located around 4 degrees northeast of Alpha is T Pyxidis,[26] a binary star system composed of a white dwarf with around 0.8 times the Sun's mass and a red dwarf that orbit each other every 1.8 hours. This system is located around 15,500 light-years away from Earth.[27] A recurrent nova, it has brightened to the 7th magnitude in the years 1890, 1902, 1920, 1944, 1966 and 2011 from a baseline of around 14th magnitude. These outbursts are thought to be due to the white dwarf accreting material from its companion and ejecting periodically.[28]

TY Pyxidis is an eclipsing binary star whose apparent magnitude ranges from 6.85 to 7.5 over 3.2 days.[29] The two components are both of spectral type G5IV with a diameter 2.2 times,[30] and mass 1.2 times that of the Sun, and revolve around each other every 3.2 days.[31] The system is classified as a RS Canum Venaticorum variable, a binary system with prominent starspot activity,[29] and lies 184 ± 5 light-years away.[18] The system emits X-rays, and analysing the emission curve over time led researchers to conclude that there was a loop of material arcing between the two stars.[32] RZ Pyxidis is another eclipsing binary system, made up of two young stars less than 200,000 years old. Both are hot blue-white stars of spectral type B7V and are around 2.5 times the size of the Sun. One is around five times as luminous as the Sun and the other around four times as luminous.[33] The system is classified as a Beta Lyrae variable, the apparent magnitude varying from 8.83 to 9.72 over 0.66 days.[34] XX Pyxidis is one of the more-studied members of a class of stars known as Delta Scuti variables[35]—short period (six hours at most) pulsating stars that have been used as standard candles and as subjects to study astroseismology.[36] Astronomers made more sense of its pulsations when it became clear that it is also a binary star system. The main star is a white main sequence star of spectral type A4V that is around 1.85 ± 0.05 times as massive as the Sun. Its companion is most likely a red dwarf of spectral type M3V, around 0.3 times as massive as the Sun. The two are very close—possibly only 3 times the diameter of the Sun between them—and orbit each other every 1.15 days. The brighter star is deformed into an egg shape.[35]

AK Pyxidis is a red giant of spectral type M5III and semi-regular variable that varies between magnitudes 6.09 and 6.51.[37] Its pulsations take place over multiple periods simultaneously of 55.5, 57.9, 86.7, 162.9 and 232.6 days.[25] UZ Pyxidis is another semi-regular variable red giant, this time a carbon star, that is around 3560 times as luminous as the Sun with a surface temperature of 3482 K, located 2116 light-years away from Earth.[20] It varies between magnitudes 6.99 and 7.83 over 159 days.[38] VY Pyxidis is a BL Herculis variable (type II Cepheid), ranging between apparent magnitudes 7.13 and 7.40 over a period of 1.24 days.[39] Located around 650 light-years distant, it shines with a luminosity approximately 45 times that of the Sun.[20]

The closest star to Earth in the constellation is Gliese 318, a white dwarf of spectral class DA5 and magnitude 11.85.[40] Its distance has been calculated to be 26 light-years,[41] or 28.7 ± 0.5 light-years distant from Earth. It has around 45% of the Sun's mass, yet only 0.15% of its luminosity.[42] WISEPC J083641.12-185947.2 is a brown dwarf of spectral type T8p located around 72 light-years from Earth. Discovered by infrared astronomy in 2011, it has a magnitude of 18.79.[43]

Planetary systems

[edit]Pyxis is home to three stars with confirmed planetary systems—all discovered by Doppler spectroscopy. A hot Jupiter, HD 73256 b, that orbits HD 73256 every 2.55 days, was discovered using the CORALIE spectrograph in 2003. The host star is a yellow star of spectral type G9V that has 69% of our Sun's luminosity, 89% of its diameter and 105% of its mass. Around 119 light-years away, it shines with an apparent magnitude of 8.08 and is around a billion years old.[44] HD 73267 b was discovered with the High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS) in 2008. It orbits HD 73267 every 1260 days, a 7 billion-year-old star of spectral type G5V that is around 89% as massive as the Sun.[45] A red dwarf of spectral type M2.5V that has around 42% the Sun's mass, Gliese 317 is orbited by two gas giant planets. Around 50 light-years distant from Earth, it is a good candidate for future searches for more terrestrial rocky planets.[46]

Deep sky objects

[edit]

Pyxis lies in the plane of the Milky Way, although part of the eastern edge is dark, with material obscuring our galaxy arm there. NGC 2818 is a planetary nebula that lies within a dim open cluster of magnitude 8.2.[47] NGC 2818A is an open cluster that lies on line of sight with it.[48] K 1-2 is a planetary nebula whose central star is a spectroscopic binary composed of two stars in close orbit with jets emanating from the system. The surface temperature of one component has been estimated at as high as 85,000 K.[49] NGC 2627 is an open cluster of magnitude 8.4 that is visible in binoculars.[48]

Discovered in 1995,[3] the Pyxis globular cluster is a 13.3 ± 1.3 billion year-old globular cluster situated around 130,000 light-years distant from Earth and around 133,000 light-years distant from the centre of the Milky Way—a region not previously thought to contain globular clusters.[50] Located in the galactic halo, it was noted to lie on the same plane as the Large Magellanic Cloud and the possibility has been raised that it might be an escaped object from that galaxy.[3]

NGC 2613 is a spiral galaxy of magnitude 10.5 which appears spindle-shaped as it is almost edge-on to observers on Earth.[51] Henize 2-10 is a dwarf galaxy which lies 30 million light-years away. It has a black hole of around a million solar masses at its centre. Known as a starburst galaxy due to very high rates of star formation, it has a bluish colour due to the huge numbers of young stars within it.[52]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Pronounced /ˈpɪksɪs/; Greek and Latin for box.[1][2]

- ^ The exception is Mensa, named for the Table Mountain. The other thirteen (alongside Pyxis) are Antlia, Caelum, Circinus, Fornax, Horologium, Microscopium, Norma, Octans, Pictor, Reticulum, Sculptor, and Telescopium.[7]

- ^ While parts of the constellation technically rise above the horizon to observers between the latitudes of 52°N and 72°N, stars within a few degrees of the horizon are to all intents and purposes unobservable.[11]

- ^ Objects of magnitude 6.5 are among the faintest visible to the unaided eye in suburban-rural transition night skies.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ pyxis. Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short. A Latin Dictionary on Perseus Project.

- ^ πυξίς. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ a b c Irwin, M. J.; Demers, Serge; Kunkel, W. E. (1995). "The PYXIS Cluster: A Newly Identified Galactic Globular Cluster". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 453: L21. Bibcode:1995ApJ...453L..21I. doi:10.1086/513301.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian (1988). "Pyxis". Star Tales. Self-published. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian. "Lacaille's Southern Planisphere of 1756". Star Tales. Self-published. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ^ Lacaille, Nicolas Louis (1756). "Relation abrégée du Voyage fait par ordre du Roi au cap de Bonne-espérance". Mémoires de l'Académie Royale des Sciences (in French): 519–92 [589].

- ^ a b c d e Wagman, Morton (2003). Lost Stars: Lost, Missing and Troublesome Stars from the Catalogues of Johannes Bayer, Nicholas Louis de Lacaille, John Flamsteed, and Sundry Others. Blacksburg, Virginia: The McDonald & Woodward Publishing Company. pp. 6–7, 261–62. ISBN 978-0-939923-78-6.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian (2006). Eyewitness Companions: Astronomy. London, England: DK Publishing (Dorling Kindersley). p. 210. ISBN 978-0-7566-4845-9.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian (1988). "Lochium Funis". Star Tales. Self-published. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ Yarnall, M. (1889). Catalogue of Stars observed at the United States Naval Observatory during the years 1845 to 1877, third edition. Washington, USA: Washington Government printing office. p. 97.

- ^ a b c d Ridpath, Ian. "Constellations: Lacerta–Vulpecula". Star Tales. self-published. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ Sasaki, Chris; Boddy, Joe (2003). Constellations: the stars and stories. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-4027-0800-8.

- ^ Russell, Henry Norris (1922). "The New International Symbols for the Constellations". Popular Astronomy. 30: 469. Bibcode:1922PA.....30..469R.

- ^ "Pyxis, Constellation Boundary". The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ Moore, Patrick; Tirion, Wil (1997). Cambridge Guide to Stars and Planets. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-521-58582-8.

- ^ Bortle, John E. (February 2001). "The Bortle Dark-Sky Scale". Sky & Telescope. Sky Publishing Corporation. Archived from the original on 31 March 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ^ a b Kaler, Jim. "Alpha Pyxidis". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f van Leeuwen, F. (2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474 (2): 653–64. arXiv:0708.1752. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. S2CID 18759600.

- ^ Nieva, María-Fernanda; Przybilla, Norbert (2014). "Fundamental properties of nearby single early B-type stars". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 566: 11. arXiv:1412.1418. Bibcode:2014A&A...566A...7N. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201423373. S2CID 119227033.

- ^ a b c d McDonald, I.; Zijlstra, A. A.; Boyer, M. L. (2012). "Fundamental Parameters and Infrared Excesses of Hipparcos Stars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 427 (1): 343–57. arXiv:1208.2037. Bibcode:2012MNRAS.427..343M. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21873.x. S2CID 118665352.

- ^ "Beta Pyxidis". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ a b Pasinetti Fracassini, L. E.; Pastori, L.; Covino, S.; Pozzi, A. (2001). "Catalogue of Apparent Diameters and Absolute Radii of Stars (CADARS) – Third edition – Comments and statistics". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 367 (2): 521–24. arXiv:astro-ph/0012289. Bibcode:2001A&A...367..521P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20000451. S2CID 425754.

- ^ "Kappa Pyxidis". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Privett, Grant; Jones, Kevin (2013). The Constellation Observing Atlas. New York, New York: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 168. ISBN 978-1-4614-7648-1.

- ^ a b Tabur, V.; Bedding, T.R. (2009). "Long-term photometry and periods for 261 nearby pulsating M giants". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 400 (4): 1945–61. arXiv:0908.3228. Bibcode:2009MNRAS.400.1945T. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.15588.x. S2CID 15358380.

- ^ Motz, Lloyd; Nathanson, Carol (1988). The Constellations. New York, New York: Doubleday. pp. 383–84. ISBN 978-0-385-17600-2.

- ^ Chesneau, O.; Meilland, A.; Banerjee, D. P. K.; Le Bouquin, J.-B.; McAlister, H.; Millour, F.; Ridgway, S. T.; Spang, A.; ten Brummelaar, T.; Wittkowski, M.; Ashok, N. M.; Benisty, M.; Berger, J.-P.; Boyajian, T.; Farrington, Ch.; Goldfinger, P. J.; Merand, A.; Nardetto, N.; Petrov, R.; Rivinius, Th.; Schaefer, G.; Touhami, Y.; Zins, G. (2011). "The 2011 outburst of the recurrent nova T Pyxidis. Evidence for a face-on bipolar ejection". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 534: 5. arXiv:1109.4534. Bibcode:2011A&A...534L..11C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201117792. S2CID 10318633. L11.

- ^ Davis, Kate (19 April 2011). "T Pyxidis: Enjoy the Silence". Variable Star of the Month. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ a b Watson, Christopher (4 January 2010). "AK Pyxidis". The International Variable Star Index. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ Strassmeier, Klaus G. (2009). "Starspots". The Astronomy and Astrophysics Review. 17 (3): 251–308. Bibcode:2009A&ARv..17..251S. doi:10.1007/s00159-009-0020-6.

- ^ Andersen, J.; Popper, D. M. (1975). "The G-type eclipsing binary TY Pyxidis". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 39: 131–34. Bibcode:1975A&A....39..131A.

- ^ Pres, Pawel; Siarkowski, Marek; Sylwester, Janusz (1995). "Soft X-ray imaging of the TY Pyx binary system - II. Modelling the interconnecting loop-like structure". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 275 (1): 43–55. Bibcode:1995MNRAS.275...43P. doi:10.1093/mnras/275.1.43.

- ^ Bell, S. A.; Malcolm, G. J. (1987). "RZ Pyxidis – an early-type marginal contact binary". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 227 (2): 481–500. Bibcode:1987MNRAS.227..481B. doi:10.1093/mnras/227.2.481. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ Watson, Christopher (4 January 2010). "RZ Pyxidis". The International Variable Star Index. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ a b Aerts, C.; Handler, G.; Arentoft, T.; Vandenbussche, B.; Medupe, R.; Sterken, C. (2002). "The δ Scuti star XX Pyx is an ellipsoidal variable". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 333 (2): L35 – L39. Bibcode:2002MNRAS.333L..35A. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2002.05627.x.

- ^ Templeton, Matthew (16 July 2010). "Delta Scuti and the Delta Scuti Variables". Variable Star of the Season. AAVSO (American Association of Variable Star Observers). Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ Watson, Christopher (25 August 2009). "AK Pyxidis". The International Variable Star Index. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ Otero, Sebastian Alberto (15 April 2012). "AK Pyxidis". The International Variable Star Index. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ Wils, Patrick (15 November 2011). "VY Pyxidis". AAVSO Website. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ Pancino, E.; Altavilla, G.; Marinoni, S.; Cocozza, G.; Carrasco, J. M.; Bellazzini, M.; Bragaglia, A.; Federici, L.; Rossetti, E.; Cacciari, C.; Balaguer Núñez, L.; Castro, A.; Figueras, F.; Fusi Pecci, F.; Galleti, S.; Gebran, M.; Jordi, C.; Lardo, C.; Masana, E.; Monguió, M.; Montegriffo, P.; Ragaini, S.; Schuster, W.; Trager, S.; Vilardell, F.; Voss, H. (2012). "The Gaia spectrophotometric standard stars survey – I. Preliminary results". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 426 (3): 1767–81. arXiv:1207.6042. Bibcode:2012MNRAS.426.1767P. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21766.x. S2CID 27564967.

- ^ Sion, Edward M. (2009). "1.The White Dwarfs Within 20 Parsecs of the Sun: Kinematics and Statistics". The Astronomical Journal. 138 (6): 1681–89. arXiv:0910.1288. Bibcode:2009AJ....138.1681S. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/138/6/1681. S2CID 119284418.

- ^ Subasavage, John P.; Jao, Wei-Chun; Henry, Todd J.; Bergeron, P.; Dufour, P.; Ianna, Philip A.; Costa, Edgardo; Méndez, René A. (2009). "The Solar Neighborhood. XXI. Parallax Results from the CTIOPI 0.9 m Program: 20 New Members of the 25 Parsec White Dwarf Sample". The Astronomical Journal. 137 (6): 4547–60. arXiv:0902.0627. Bibcode:2009AJ....137.4547S. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/137/6/4547. S2CID 14696597.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, J. Davy; Gelino, Christopher R.; Cushing, Michael C.; Mace, Gregory N.; Griffith, Roger L.; Skrutskie, Michael F.; Marsh, Kenneth A.; Wright, Edward L.; Eisenhardt, Peter R.; McLean, Ian S.; Mainzer, Amanda K.; Burgasser, Adam J.; Tinney, C. G.; Parker, Stephen; Salter, Graeme (2012). "Further Defining Spectral Type "Y" and Exploring the Low-mass End of the Field Brown Dwarf Mass Function". The Astrophysical Journal. 753 (2): 156. arXiv:1205.2122. Bibcode:2012ApJ...753..156K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/753/2/156. S2CID 119279752.

- ^ Udry, S.; Mayor, M.; Clausen, J. V.; Freyhammer, L. M.; Helt, B. E.; Lovis, C.; Naef, D.; Olsen, E. H.; Pepe, F. (2003). "The CORALIE survey for southern extra-solar planets X. A Hot Jupiter orbiting HD 73256". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 407 (2): 679–84. arXiv:astro-ph/0304248. Bibcode:2003A&A...407..679U. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20030815. S2CID 118889984.

- ^ Moutou, C.; Mayor, M.; Lo Curto, G.; Udry, S.; Bouchy, F.; Benz, W.; Lovis, C.; Naef, D.; Pepe, F.; Queloz, D.; Santos, N. C. (2009). "The HARPS search for southern extra-solar planets XVII. Six long-period giant planets around BD −17 0063, HD 20868, HD 73267, HD 131664, HD 145377, HD 153950". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 496 (2): 513–19. arXiv:0810.4662. Bibcode:2009A&A...496..513M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200810941. S2CID 116707055.

- ^ Anglada-Escude, Guillem; Boss, Alan P.; Weinberger, Alycia J.; Thompson, Ian B.; Butler, R. Paul; Vogt, Steven S.; Rivera, Eugenio J. (2012). "Astrometry and radial velocities of the planet host M dwarf Gliese 317: new trigonometric distance, metallicity and upper limit to the mass of Gliese 317 b". The Astrophysical Journal. 764 (1): 37A. arXiv:1111.2623. Bibcode:2012ApJ...746...37A. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/746/1/37. S2CID 118526264.

- ^ Inglis, Mike (2004). Astronomy of the Milky Way: Observer's Guide to the Southern Sky. New York, New York: Springer. ISBN 1-85233-742-7.

- ^ a b Inglis, Mike (2013). Observer's Guide to Star Clusters. New York, New York: Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 202–03. ISBN 978-1-4614-7567-5.

- ^ Exter, K. M.; Pollacco, D. L.; Bell, S. A. (2003). "The planetary nebula K 1-2 and its binary central star VW Pyx" (PDF). Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 341 (4): 1349–59. Bibcode:2003MNRAS.341.1349E. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2003.06505.x.

- ^ Sarajedini, Ata; Geisler, Doug (1996). "Deep Photometry of the Outer Halo Globular Cluster in PYXIS". Astronomical Journal. 112: 2013. Bibcode:1996AJ....112.2013S. doi:10.1086/118159.

- ^ O'Meara, Stephen James (2007). Steve O'Meara's Herschel 400 Observing Guide. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85893-9.

- ^ "Henize 2–10: A Surprisingly Close Look at the Early Cosmos". Chandra X-Ray Observatory. NASA. Retrieved 6 October 2012.