Putumayo genocide

| Putumayo genocide | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Amazon rubber boom | |

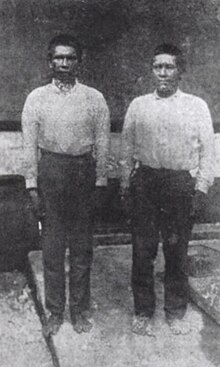

Huitoto natives in conditions of slavery | |

| Location | Colombia and Peru |

| Date | 1879 – 1930 |

Attack type | Slavery, genocidal rape, torture, crimes against humanity |

| Deaths | 32,000[1] to 40,000+[2][3][4] |

| Perpetrators | Peruvian Amazon Company |

The Putumayo genocide (Spanish: genocidio del Putumayo) refers to the severe exploitation and subsequent ethnocide of the indigenous population in the Putumayo region.

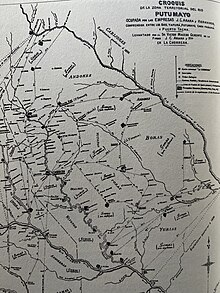

The booms of raw materials incentivized the exploration and occupation of uncolonised land in the Amazon by several South American countries, gradually leading to the subjugation of the local tribes in the pursuit of rubber extraction. The genocide was primarily perpetrated by the enterprise of Peruvian rubber baron Julio César Arana during the Amazon rubber boom from 1879 to 1911. Arana's company, along with Benjamín Larrañaga, first enslaved the indigenous population and subjected them to dreadful brutality. In 1907, Arana registered the Peruvian Amazon Company on the London Stock Exchange, this company assumed control over Arana's assets in the Putumayo River basin, notably along the Igara Paraná, Cara paraná and Cahuinari tributaries.

Arana's company made the local indigenous population work under deteriorated conditions, which led to mass death as well as extreme punishment. Some of the indigenous groups exploited by Peruvian and Colombian rubber firms were Huitoto, Bora, Andoque, Ocaina, Nonuya, Muinanes and Resígaros. The main figures of the Peruvian Amazon Company, including Elías Martinengui, Andrés O'Donnell, and the Rodríguez brothers, committed mass starvation, torture, and killings. The company educated a group of native males—Muchachos de Confianza—in policing their fellow men and torturing them.

Nine in every ten targeted Amazonian populations were destroyed in the Putumayo genocide. The company continued its work even after 215 arrest warrants were issued against its workers in 1911. The dissolution of the company did not stop it from providing Arana and his partners with means to subjugate the native population of the Putumayo region. At least 6,719 indigenous people were forced by administrators of Arana's enterprise to emigrate from their traditional territory in the Putumayo River basin between 1924 and 1930, half of this group perished from disease and other factors after the migrations. Although the genocide is of great historical significance, it remains relatively unknown. Eyewitness accounts collected by Benjamin Saldaña Rocca, Walter Ernest Hardenburg and Roger Casement brought the atrocities to global attention.

| Part of a series on |

| Genocide of indigenous peoples |

|---|

| Issues |

Background

[edit]The Cinchona boom[2] and the beginning of the Amazon rubber boom in 1879 encouraged exploration and settlement of uncolonized land between Brazil, Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia.[5] Rafael Reyes carried out one of the first main expeditions in the Putumayo River basin in 1874 in search of Cinchona pubescens,[6] a plant that produces quinine.[7][8][a]

Reyes operated a firm in the Putumayo between 1874 and 1884[9] and stationed his headquarters at La Sofia, the furthest point of navigation for steamboats on the Upper Putumayo River.[10][11][12] Members of this expedition later returned to the region they had previously noticed the abundance of rubber trees and indigenous tribes to potentially use as a workforce. Between 1884 and 1895, a wave of new people sought to exploit these resources; these people included Calderón Hermanos, Crisóstomo Hernández, and Benjamin Larrañaga,[13][14][15] the latter two being Colombians and veterans of Reyes' first expedition to the region in 1874.[16]

In his memoir, Reyes described the occurrence of human trafficking on the Putumayo River and he noted that this trafficking was active by the time of his first expedition to the region.[17] According to Reyes, the traffickers encouraged strong indigenous tribes to go to war against weaker neighboring tribes, the captives from these conflicts were traded for merchandize. The traffickers loaded their human cargo onto boats, where "many of these individuals died of hunger or mistreatment".[18] The voyage between the Putumayo River and the final destination for the trafficked indigenous people could take weeks, once at that final destination, which was typically in Brazil, these people were treated as slaves.[19][20] Reyes compared this "barbaric" human trafficking to the African slave trade and he wrote that indigenous tribes in the Putumayo "tend to disappear, wiped out by epidemics, abused and slaughtered by those who hunt and trade in men". Reyes claimed that his company managed to effectively end the trafficking on indigenous people in Colombian territory during its operations however the company was unable to support itself and went into liquidation in 1884.[21][20]

Benjamin Larrañaga and his company initially settled on the left bank of the Upper Igara Paraná River, at a point named Ultimo Retiro. This was the location of first contact between Larrañaga and the Putumayo's indigenous people, Larrañaga and his companions traded with these indigenous people and lodged within the houses of the latter group. The group of Colombians decided to travel further down river and a portion of Larrañaga's expedition stayed at Ultimo Retiro, this group continued along the river until they reached a waterfall which prevented any further navigation. The Colombians continued their journey on foot, moving around the waterfall and came into contact with members of Aimenes nation. Larrañaga was able to successfully trade with the Aimenes people, exchanging merchandize for lumps of rubber,[22] which the Colombians taught the local indigenous people how to produce.[23][b] Some of the Colombians left behind at Ultimo Retiro were directed by Larrañaga to travel down river to the waterfall in order to help establish a settlement called Colonia Indiana, which later became known as La Chorrera. Overtime, Larrañaga was able to induce the indigenous people around the stations of Ultimo Retiro, Occidente, Oriente, and Santa Julia into collecting rubber for him. "[A] considerable quantity" of rubber was collected by Larrañaga's enterprise after several months and sent to Para, Brazil where the rubber was then sold. The profits were split between Benjamin Larrañaga and Gregorio Calderón however they "both wasted it entirely and fell into extreme poverty."[22][c]

Around this time, a group of Colombians led by Rafael Tobar, Aquiléo Torres, and Cecilio Plata initiated a campaign of conquest against natives in the areas that later became known as Entre Rios, Atenas, and La Sabana.[27][28][d] Afterwards, Crisóstomo Hernández, Gregorio Calderón and several other Colombians led an expedition towards the Cara Paraná River; they began another attempt to colonize the region and induce the local indigenous people into delivering rubber for them at El Encanto, a settlement established by Calderón.[32][33][e] Some of the Colombians that accompanied the aforementioned expedition were initially debt peons employed by Benjamin Larrañaga then recruited by Gregorio Calderón and or his two brothers.[28][27] These Colombian patrons decided to exploit the Huitotos, the Andokes, and the Boras tribes into debt or enslavement with the goal of extracting rubber.[36][f][g] According to Roger Casement in 1913:

The foundations thus laid by Crisostomo Hernandez and Larrañaga in 1886 grew, not without bloodshed and many killings of the Indians, into a widespread series of Colombian settlements along the banks of the Caraparaná and Igaraparana, and even in the country stretching between the latter river and the Japura [or Caquetá] and on the upper waters of the Cahuinari.[39]

Joaquin Rocha, a Colombian who travelled through the Putumayo region, said by 1897, Crisóstomo Hernández had subdued the entire Caraparaná region and a large portion of the Igaraparana River.[40][41][42] Hernández waged war against the tribes that would not work or trade with him; during these conflicts, Hernandez acquired aid from tribes he had previously entrapped.[40] In his 1905 book, Rocha provided an eyewitness account of a massacre that was relayed to him by an ex-employee of Hernandez.[43] This source stated Hernandez ordered his employees to exterminate a tribe of Huitotos known as the Uruhuai, including the men, women and children, because they were rumoured to have practised cannibalism.[44] Hernandez was later killed in an accident while one of his employees was handing him a loaded rifle.[45][46] In his 1991 book, anthropologist Michael Taussig examined the history and conditions that led to the Putumayo genocide, and Peruvian anthropologist Alberto Chirif noted Taussig's examination of Crisostomo Hernandez "demonstrates that the massacres against the indigenous people in the Putumayo were already taking place before [Julio César] Arana's arrival".[47][48]

Arana's monopolization of the Putumayo

[edit]In 1896, Julio César Arana expanded his small peddling business in Iquitos and began to trade with Colombians in the region.[49][50] At the time, it was easier for the Colombians to secure supplies from Iquitos rather than from Colombian territory.[51][52][53] A year later, Arana's most-successful competitors in Peru Carlos Fitzcarrald and Antonio de Vaca Diez died in a boating accident in the Urubamba River.[54] Along with the Putumayo, the basins of the Urubamba and the Madre de Dios were the biggest producers of rubber in Peru. After the collapse of the Fitzcarrald's and Vaca Diez' enterprises and their partnership with Nícolas Suarez, the Putumayo became the most-significant rubber-producing region of Peru.[55]

Arana entered a partnership with Benjamin Larrañaga, forming Larrañaga, Arana y compañia in 1902, the assets of this company later became a part of J.C. Arana y Hermanos, which was established near the end of 1903 to consolidate Arana's business interests.[56] Prior to the first partnership, Arana had intervened in a conflict at La Chorrera with the Larrañagas against the Calderón brothers as well as Rafael Tobar, Aquiléo Torres, and Cecilio Plata.[57][58] The latter group had organized an expedition of 50 armed men to attack La Chorrera, they wanted to evict the Larrañagas from the region and acquire their properties. Arana arrived at La Chorrera on the steamship Putumayo while both groups of Colombians were preparing for the conflict.[59][28] At the time, both the Larrañaga and Calderón rubber firms were indebted to Arana.[60]

Arana, acting as a representative for the Larrañagas, paid Tobar and his companions 50,000 Peruvian soles in exchange for the custody of "conquered tribes" while the Calderón's were paid 14,000 soles for a settlement built on the Lower Igaraparana River.[28][58][h] While the source of this information, judge Romulo Paredes,[63][64] did not provide a date for this intervention at La Chorrera, Rafael Tobar, Cecilio Plata and Aquileo Torres were imprisoned on steamship Putumayo in July 1901 prior to being sent to prison at Iquitos.[65][66] Paredes emphasized that Tobar and his companions were obliged by Arana to definitively withdraw from the Putumayo and to forsake any right to establish future operations in the region.[28][61][i][j] The settlements of Entre Rios, Atenas and La Sabana, which were founded by Tobar and his companions,[27] became assets for Arana's enterprise.[70][71][29] A chapter of Las crueldades en el Putumayo y en el Caquetá, written by Rafael Uribe Uribe, focuses on the arrest of Tobar and Plata, along with Arana's acquisition of several other Colombian estates. According to the chronology of Uribe's statement, the Colombian patrons were arrested on the steamship Putumayo then taken to prison at Iquitos. Tobar along with his partner Plata was informed that in order to secure their release from prison they would have to surrender their estates and "the numerous Indians he dominated", which had been induced to collect rubber. Uribe claimed that all of this was desired by Arana's enterprise for their own assets, as well as to bolster the amount of rubber shipped through the Iquitos customs house.[68] [k]

One of the first notable massacres of Colombians between the Putumayo and Caqueta River basins occurred in 1903 near the Andoque nation's traditional territory. In 1903, Emilio Gutierrez led a group of around sixty armed individuals, from Colombia and Brazil, on an expedition into the Caqueta, this group intended to "conquistar" the local indigenous people as well as establish rubber stations.[72][73][74] There are varying accounts regarding how Gutierrez and his group were killed. Two sources of information for this subject, Joaquin Rocha and Andrés O'Donnell claimed that Gutierrez, along with his companions, were lulled into a false sense of security by the indigenous people they encountered. Both accounts noted that Gutierrez and his expedition were killed while they were asleep at night[72][75] Rocha specified that the local indigenous people launched several attacks, around the same time, against the network that Gutierrez had established in the area and thirty of Gutierrez's men were killed.[76][73] O'Donnell provided Roger Casement with the information he knew on this case as well as details on several other similar incidents[77][l] "wherein the Colombians had been killed by the Indians they were seeking to enslave."[72]

Casement wrote that "[t]errible reprisals subsequently fell upon these Indians and all in the neighbourhood who were held responsible for this killing of the Colombians in 1903 and later years."[78] Rocha noted that when the white patrons in the area heard about these killings they sent Muchachos de Confianza to hunt down the local indigenous people that were held responsible. Rocha wrote that "some of whom were killed outright, some taken as prisoners for the whites, while the majority escaped. Some were captured and eaten by these Indian mercenaries."[76][73] According to Rocha, this was the "most serious uprising" to have occurred in the region at that time and afterwards, reprisals against the local indigenous people became more frequent [76] The settlement[s] established by Gutierrez were sacked and burned.[69] The book Las crueldades en el Putumayo y en el Caquetá contains two documents which claim that the killing of Gutierrez and his companions was organized by Benjamin and Rafael Larrañaga on behalf of Arana's enterprise.[79] Another Colombian source claimed that Gutierrez, along with around forty of his companions were killed by Boras people recruited by Benjamin Larrañaga. Shortly after these killings Rafael Larrañaga and several agents from his fathers firm arrived at Gutierrez's area of operation, they took all of the products and merchandize located there to La Chorrera.[80]

1903 massacres at La Chorrera

[edit]The first set of arrest warrants levied against the perpetrators of the Putumayo genocide was filed against men that participated in a massacre of Ocaina people at La Chorrera on September 23–24 of 1903.[81][82] This massacre occurred during the delivery of rubber to La Chorrera from its distant subsections and eyewitness sources vary on the number of victims, the claims in these accounts range from 25 to 40 indigenous people being killed during this time. The indigenous group delivering this rubber consisted of around seven hundred Ocaina's which were under the management of Ursenio Bucelli, a patron. Several of the eyewitnesses and participants of this massacre provided depositions to the judicial commission in 1911, many of them claimed that these killings were instigated by Rafael Larrañaga and his father Benjamin. One of the deponents claimed that these killings were perpetrated in revenge for the deaths of several white people throughout the region.[83] Rafael was also responsible for the perpetration of another massacre on the river bank opposite of La Chorrera in 1903, during which around thirty people from the Puineses and Renuicuese nations were killed because Rafael thought these people intended to revolt as well as attack La Chorrera.[84] The Peruvian government first established a garrison on the Igaraparana River in 1902,[85] at La Chorrera.[86] Several of the men which provided depositions on the massacre of Ocainas in 1903 also claimed that they witnessed members of the Peruvian garrison at La Chorrera, as well as their commander, Lieutenant Risco, flagellate members of the Ayemenes nation on behalf of Rafael.[87]

After Benjamin Larrañaga's death on December 21, 1903, Arana bought out Rafael Larrañaga's share of the company, "taking advantage of their ignorance and stupidity to rob them scandalously".[88][89] Benjamin was said to have died from symptoms of arsenic poisoning.[90][91][92] Afterwards, his son, Rafael, was imprisoned in Iquitos and given an ultimatum to either sell his property for a certain amount or to die in prison, ultimately he disappeared.[90][91][m] According to Norman Thomson's information the Larrañaga estate was sold for £18,000.[90] On April 8, 1904, "Arana, Vega y Larrañaga" was formally registered in a deed granted by the public notary of Iquitos, the business partners on this deed were Julio Arana, Pablo Zumaeta, Juan Bautista Vega and Rafael Larrañaga.[93][94] Pablo Zumaeta was Julio Arana's brother-in-law while Juan B. Vega was the Colombian consul-general to Iquitos in 1904.[95] The deed also documented the liquidation of "Larrañaga, Arana y compañia". The deed stated that the companies assets, including properties or "reducciones", were valued at 200,000 Peruvian soles, half of which corresponded to Rafael Larrañaga and the other half to Arana.[96] In the words of the aforementioned deed, the companies assets owned by Arana were invested in "merchandise, boats, supplies for the indigenous Indians of that region; and in debts of the personnel (company employees) that reduces them and forces the Indians to work in those fields."[97][98]

The establishment of Matanzas

[edit]In order to secure a larger work force to control the indigenous population indebted to J.C. Arana y Hermanos, over the course of a twelve-month period in 1904, the company employed 257 Barbadians on two-year work contracts . Out of that group, 196 of those Barbadians ended up in the Putumayo, the first group of Barbadians to arrive at La Chorrera consisted of 30 men and 5 women.[99][100] Armando Normand was hired along with the first contingent of Barbadians sent to the Putumayo, he was an accountant which was educated in London and initially employed as a translator and intermediary for this new Barbadian work force.[101] Normand later became known as one of the "worst criminals on the Putumayo" due to his cruel management of Matanzas between 1905 and 1910.[102][103] According to one of those Barbadians, the expedition to establish the rubber station of Matanzas left La Chorrera on November 17 of 1904, they were armed with Winchester rifles as well as a large supply of ammunition for their firearms.[99]

The Matanzas rubber station, which was originally named "Andokes", was established as a joint financial venture between Arana and Ramon Sanchez, a Colombian patron.[101] The station became a "centre of a series of raids organised by the Colombian head of it," and in Roger Casement's words the Barbadians were sent to accompany Sanchez "on a mission of vengeance and rubber-gathering into the Andokes country."[104][78] This "mission of vengeance" may have been retaliation for the killing of Emilio Gutierrez and his companions, or another incident that occurred in May 1904 according to Normand. During the aforementioned incident Sanchez was leading an expedition of 28 men and this group was ambushed by the local indigenous people, Sanchez managed to flee towards Iquitos with 8 other survivors from his group.[105]

Arana later bought Ramon Sanchez's share in the Matanzas estate after he became the subject of several complaints which were charging Sanchez with physically abusing the Barbadian employees subordinate to him.[106][107][n] Normand was also implicated with physically assaulting two of the Barbadian men however he retained employment with Arana's company.[107] According to Arana in 1913, it was the administrators in the Putumayo who recommended Normand to manage the Matanzas station, and installed him as such.[101] Casement wrote about the employment of Barbadians at Matanzas and the operations of the station in his report. He specified that "[t]he duties fulfilled by Barbados men at Matanzas were those that they performed elsewhere throughout the district, and in citing this station as an instance I am illustrating what took place at a dozen or more different centers of rubber collection."[108][109]

Consolidation of Arana's enterprise

[edit]The Calderón brothers at El Encanto became indebted to Arana's enterprise and sold their property to Arana in July 1905.[110][49] Along with the acquisition of El Encanto, there were 3,500 Huitoto natives on the estate dedicated to the extraction of rubber who became part of Arana's workforce.[111][112] Around 1906, an official from the Department of Loreto made an estimation of the indigenous population inhabiting territory in the Putumayo which the Peruvian Government claimed to own, most of that population was listed as working with one of Arana's various rubber firms.[112] This official emphasized that these numbers excluded indigenous people who had, by that time, not come into reported contact with Peruvian settlers, he gave the following information:

| Indigenous nation | Territory | "Trabajan con" ["Working with"] | Estimated population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angoteros | Campuya - San Miguel tributaries | N/A | 1,000 |

| Macaguajes and Coreguajes | San Miguel - Gueppi tributaries | N/A | 500 |

| Huitotos of the Caraparaná | Caraparaná | Calderón, Arana & C. | 3,500 |

| Huitotos of the Igaraparná | Igaraparná | Arana, Vega & C. | 4,000 |

| Ocainas | Igaraparná | Arana, Vega & C. | 300 |

| Fititas | Igaraparná | Arana, Vega & C. | 150 |

| Nernuígaros | Right bank of the Igaraparná | Arana, Vega & C. | 150 |

| Muinanes | Igaraparná - Upper Cahuinari tributary | Arana, Vega & C. | 800 |

| Nonuyas | Igaraparná | Arana, Vega & C. | 200 |

| Boras | Confluence of the Igaraparná with the Putumayo - Middle Cahuinari tributary | Arana, Vega & C. | 3,000 |

By 1906, Arana was the dominant force on the Igaraparaná River; he was only challenged by insignificant bands of Colombian rubber tappers and indigenous tribes who were not yet under his control.[49][114] To administer his territory, the management was split between the two departments of La Chorrera and El Encanto. La Chorrera was the company headquarters along the Igara Paraná River while the headquarters for the Caraparaná River was in El Encanto.[115][116][117] All of the subsections and rubber tappers had their products delivered to their headquarters to be exported through Iquitos.[118]

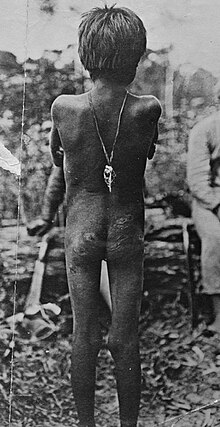

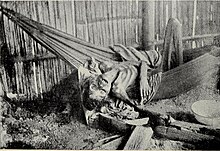

At the hands of Arana's company, natives suffered enslavement, kidnapping, separation of families, rape, starvation, use for target practice, flagellation, immolation, dismemberment, and other extreme violence.[119][120] People who were too old or no longer able to work were murdered. Most of the elderly natives were killed during the early stages of the genocide because the slavers viewed their advice as dangerous.[121][122][123][o]

In 1907 after successful business meetings in England, Julio Arana formed his company into the Peruvian Amazon Company,[126][127] to which the Government of Peru ceded the Amazon territories north of Loreto after the company's founder Arana purchased the land. Shortly after, private hosts of Arana – brought from Barbados –[128] which consisted of forcing natives to work for him in exchange for "favors and protection"; the offer could not be refused because disagreements led to their kidnapping by mercenaries paid by the company. Native people were subjected to isolation in remote areas to collect rubber in inhuman conditions and were punished with death or internment in labour camps if they did not collect the required amount of rubber. Ninety percent of the affected Amazonian populations were annihilated.[129] Several of the inquiring parties that later investigated the practices of Arana's company, notably Walter E. Hardenburg, Roger Casement and Romulo Paredes, emphasized that payment to managers of rubber stations through commissions based on the amount of rubber collected was one of the principal causes for crime in the Putumayo region.[130][131][p]

The rubber industry

[edit]During the Amazon rubber boom, indigenous people from different regions of the Amazon suffered similar atrocities as those perpetrated against the Putumayo's indigenous nations. The Peruvian government was aware of instances barbaric crimes and slave raids against indigenous people along the Marañon and Ucayali Rivers as early as 1903 and 1906.[133][134] Anthropologist Søren Hvalkof claimed that slave raids along the Ucayali were common during the rubber boom and affected all of the region's indigenous people. The enterprise of Peruvian rubber baron Carlos Fitzcarrald was dependent on slave labor and according to Hvalkof, Fitzcarrald "maintained a similar regime of horror" to Julio César Arana while in the Ucayali.[135] Historian John Tully noted that atrocities similar to the Putumayo genocide were also occurring during the rubber boom in Bolivia under the enterprise of Nicolás Suárez.[136] Several government officials of Peru in Loreto, including Hildebrando Fuentes, reported instances of slave raiding and human trafficking between 1903 and 1904. Fuentes claimed that the governments inability to respond to these crimes was due to the fact that "[t]hey do all this significantly beyond the reach of authority."[137]

The atrocities perpetrated against indigenous people during the rubber boom were only subjected to a systematic inquiry in the Putumayo River basin.[135] Tully also wrote that "[t]he strict legal definition of genocide applies to cases where there is a deliberate attempt to exterminate people, but the standard text on the subject regards the Putumayo killings as just that."[136] Roger Casement believed that the entire indigenous population in the rubber producing regions of Peru was enslaved and the crimes perpetrated against them corresponded to their resistance to enslavement. In Casement's words, "[t]he wilder the Indian the wickeder the slavery."[138] Writing in 1910 Casement described that in the Putumayo region there existed a "system [of] not merely slavery but extermination".[139][140] Casement also noted, while citing English Lieutenant Henry Lister Maw, that slave raiding along the Putumayo and Caqueta Rivers had been going along for over 100 years at the time of his writing in 1910. This industry of human trafficking had been continued by Portuguese and Brazilian men.[141]

Indigenous workforce

[edit]To secure their workforce, the Peruvians and Colombians initiated slave raids, during which indigenous people were either captured or killed. The slavers would bring in chiefs and their tribes, inducing them to collect rubber under the threat of death. Chiefs who refused or did not bring in enough rubber were murdered as examples. Through fear and entrapment of natives into a debt relationship, the exploiters managed a system of slavery.[142][143] Some natives were recruited at a very young age to act as trusted killers for the company; these natives became known as muchachos de confianza. The Barbadians and muchachos de confianza acted as enforcers and executioners for plantation managers.[144][145] They managed the collection of rubber and tribal chiefs who were allowed to live.[146]

Exploiters would send natives into the wild forest to collect rubber. Managers working for the Peruvian Amazon Company earned a commission that was based on the amount of rubber their indigenous workers collected.[147] A weight quota that was dictated by a manager was set for each plantation. Punishments for not meeting the quota included flagellation, immolation, dismemberment, and execution.[148]

As well as collecting rubber for the company, natives were expected to provide food and firewood; labour for clearing paths in the forest for roads between stations, the construction of bridges and buildings, and for clearing the forest around the stations; and "every other conceivable form of demand", including giving their children or wives to company employees. Natives worked without pay for the company under threat of terrorization or death.[149] The Amazon Journal of Roger Casement[q] and The Putumayo, The Devil's Paradise by Walter Hardenburg include numerous mentions of starvation among the indigenous population. According to Casement:

The trees are valueless without the Indians, who, besides getting rubber for them, do everything else these creatures need – feed them, build for them, run for them and carry for them and supply them with wives and concubines. They couldn't get this done by persuasion, so they slew and massacred and enslaved by terror, and that is the foundation. What we see today is merely the logical sequence of events – the cowed and entirely subdued Indians, reduced in numbers, hopelessly obedient, with no refuge and no retreat, and no redress.[151]

Muchachos de Confianza

[edit]Muchachos de Confianza ("boys of trust") were a group of Indigenous males who were trained at a young age to act as killers and torturers against the native workforce. They were often employed in areas where their tribes had long-standing hostilities or were traditionally antagonistic.[152] Muchachos de Confianza were also referred to as racionales ("rationals") a part of an imposed hierarchy that divided "semi-civilized" natives and those who were considered non-civilized.[153] The Peruvian Amazon Company outfitted its muchachos with Winchester rifles and shotguns.[154][155] Muchachos risked death if they disobeyed.

Judge Romulo Paredes, wrote they "place at the disposal of those chiefs their special instincts, such as sense of direction, scent, their sobriety, and their knowledge of the mountains, in order that nobody might escape their fury". According to Paredes, muchachos were often the authors of fictitious uprisings or similar rebellions. These lies were encouraged by the fact they were rewarded for their services.[156][r] Roger Casement described the system as "Boras Indians murdering Huitotos and vice versa for the pleasure, or supposed profit, of their masters, who in the end turn on these (from a variety of motives) and kill them".[158][s] Casement was also convinced the agency at La Chorrera did not inquire into disappearances of muchachos.[159][t] Casement estimated that the muchachos de confianza outnumbered Peruvian Amazon Company employees in the Putumayo by a ratio of two to one.[154] In certain areas of the Peruvian Amazon Company estate, the management of the enslaved rubber-collecting workforce was dependent on the muchachos de confianza.[u] There were numerous cases of rebellions perpetrated by muchachos de confianza but they were all small-scale incidents.[v] According to Casement, one of these rebellions was a representative case for the practice of grooming muchachos de confianzas:

Incidentally, too, it illustrates the depravity entailed by the whole system. 'Chico' was one of the 'civilized' Indians of Abisinia – one of those armed and drilled to obey and execute the orders of the civilisers on the wild, or in other words, defenceless Indians. With what result? He revolts. He becomes 'a bandit', an armed terror 'threatening the lives of white men even',[w] and so is shot out of hand by a labourer of British birth in the Company's service.[x][162]

Correrias

[edit]One method for the accumulation and expansion of a native workforce by rubber extracting firms in the Putumayo, were correrias ("forays" or "chasings").[163] Employees of the Peruvian Amazon Company also referred to these raids as "commissions".[164][165] These were hunting parties or slave raids that were sent out to either kill or capture natives.[166][167][168][y] Correrias were also sent out in the event of natives running away or as a consequence of the failure of a group to collect enough rubber.[170] Natives caught in these raids were often put in chains and then subjected to the cepo on their arrival to a rubber station.[171] Correrias are known to have continued up to 1910, and that year at least two raids carried out across the Caqueta River. One of these expeditions was carried out by Augusto Jímenez; twenty-one natives and three Colombian men were captured.[172] The other raid was carried out by Armando Normand, and spent at least twenty-one days away from Matanzas, six of which were spent in Colombian territory across the Caqueta.[173][174] Normand's group captured six natives.[174][z] Joshua Dyall, a Barbadian that was employed with Normand in 1904, reported that Normand and his fellow managers gave orders to their subordinates to shoot any indigenous people that they could not capture. This was done "to frighten the Indians and make them come in, because if they were killed for running away they would be less likely to run."[176]

The Peruvian Amazon Company

[edit]The Peruvian Amazon Rubber Company was registered in London on September 6, 1907,[177][aa] as a successor to J.C. Arana y Hermanos, whose assets the new company acquired.[179] The word rubber was later removed from the Peruvian Amazon Company's name. The old company employed 196 Barbadian men in the Putumayo around 1904, many of whom became employed by the Peruvian Amazon Company.[100][180] These Barbadians were British subjects[181][182][183] and later they were at the center of the British Foreign Office's investigation into allegations of abuse as well as slavery levied against the Peruvian Amazon Company. The testimonies of 30 Barbadian men were transcribed and then examined by Roger Casement in 1910, these depositions became the primary source of evidence for the Foreign Office regarding the atrocities and abuse perpetrated against the Putumayo's indigenous population.[184][185]

Eugene Robuchon drafted the company prospectus and the Peruvian consul-general Carlos Rey De Castro was its editor.[186] Rey de Castro's editing process intended to portray this new company as a "civilizing force" and led to the removal of several paragraphs Robuchon wrote from the final publication.[187][188] The prospectus stated there were more than forty stations delivering rubber to La Chorrera's agency and eighteen stations delivering to El Encanto.[189]

In 1910, when Roger Casement investigated the Peruvian Amazon Company books in Manaus, he found Rey de Castro had an outstanding debt of between £4,000 and £5,000 to the Peruvian Amazon Company.[190][186][191] Casement wrote: "the English Company is only English in name".[192][ab]

In June 1911, 215 arrest warrants were issued against employees of the Peruvian Amazon Company, primarily among La Chorrera's agency. They were implicated "with a multiplicity of murders and tortures of the Indians all through that region".[81][194][195]

Rubber stations

[edit]The Peruvian Amazon Company had dozens of plantations throughout the Putumayo region.[189] Many of these settlements were acquired through exploitative business deals or by force, and were used as centres of control for the company against the Natives. Slave raids to secure an indigenous workforce, which would have to deliver the rubber to the nearest company station or face torture and possibly death, were carried out from the stations. Plantations usually consisted of a centralized settlement surrounded by cleared forest. Any attack against these stations would have to face open ground with no cover from bullets. In reference to the stations located further inland, Seymour Bell, who was a member of the 1910 investigatory commission, stated stations "were all really 'forts' ". [196]

Depending on the local station, natives could walk as far as 60 miles (97 km) while carrying between 100 and 165 pounds (45 and 75 kg) of rubber. Often, these couriers were given little or no food on their journey and had to scavenge for food.[197] The children and family of these native rubber tappers would often travel together; if not, it was likely those dependents could starve to death.[198]

La Chorrera

[edit]La Chorrera was an important settlement along the Igaraparaná River during the rubber boom. It was initially settled by Colombian rubber exporters but had come into the possession of Julio Cesar Arana by the beginning of 1904.[49][199]

Some of the first reports of the Putumayo genocide regarding the killing of 25-40 Ocaina natives originated at La Chorrera in September 1903.[200][201][202] Two witnesses gave depositions to Benjamin Saldaña Rocca about the killings, which they stated were instigated by Rafael Larrañaga and Victor Macedo.[203][200][204] The natives were flogged for hours, and later shot and burnt.[205] Arana purchased the Larrañaga share of La Chorrera and assumed control over the Igaraparaná River shortly after this incident.[89] A judge who was sent to investigate the region in 1911 later corroborated this report.[206][ac] On April 7, 1911, the judge issued twenty-two arrest warrants against individuals who had participated in the 1903 massacre of Ocaina natives. They were implicated with "the crime of flogging and flaying thirty Ocainas Indians and then burning them alive".[81][208] Another set of warrants was issued against 215 employees of La Chorrera's agency for their perpetration of crimes against the local natives.[81][209]

Sometime between 1903 and 1906, Macedo became the manager of Arana's company at La Chorrera, which operated as a regional headquarters on the Igaraparaná.[116][189] In 1906, Macedo was said to have given an order to:

kill all mutilated Indians at once for the following reasons: first, because they consumed food although they could not work; and second, because it looked bad to have these mutilated wretches running about. This wise precaution of Macedo's makes it difficult to find any mutilated Indians there, in spite of the number of mutilations; for, obeying this order, the executioners kill all the Indians they mutilate, after they have suffered what they consider a sufficient space of time.[210]

By 1907, La Chorrera's agency retained effective control over the land between the Igaraparaná and Caqueta Rivers.[211][212] The stations of La Sabana, Santa Catalina, Atenas, Entre Rios, Occidente, Abisinia, Matanzas, La China, Urania, and Ultimo Retiro delivered their rubber to La Chorrera.[117][213] All of these sections were reported to practice flagellation of natives, and on a number of occasions, natives died the wounds caused by the floggings.[214][215] The scarification of wounds from flogging were termed the "Mark of Arana".[216] Starvation was also used to punish natives; according to Roger Casement: "[d]eliberate starvation was again and again resorted to, but this not where it was desired merely to frighten, but where the intention was to kill. Men and women were kept prisoners in the station stocks until they died of hunger."[217][218]

Between 1903 and 1910, Andrés O'Donnell managed the station of Entre Rios, which was another important part of La Chorrera's agency.[219] O'Donnell was first incriminated in the Putumayo genocide by Marcial Gorries, who had worked for the Peruvian Amazon Company. In a 1907 letter to Saldaña Rocca, Marcial wrote: "O'Donnell, who has not killed Indians with his own hands, but who has ordered over five hundred Indians to be killed".[220] The cepo at Entre Rios had twenty-four holes that could restrict limbs.[221] Natives at this station also suffered from starvation, and the journey to deliver rubber for a fabrico resulted in many deaths each year.[222] On top of the journey from Entre Rios to La Chorrera, some of the enslaved natives lived 25–30 miles (40–48 km) away.[222] In 1910, O'Donnell told Casement he only required two fabricos from his station, and brought in around 16,000 kg (35,000 lb) for each of them but the Barbadian Frederick Bishop stated this was false, and the real quantity was closer to 24,000 kg (53,000 lb) every collection period.[223][ad]

Bishop stated he had often seen men carrying 40–45 kg (88–99 lb) of rubber to Puerto Peruano, from where it was taken to La Chorrera.[222][ae] According to the Entre Rios staff list, twenty-three employees were stationed there, which was "the local force for controlling the life and limb of every Indian in the district".[af] While en route to Puerto Peruano, Roger Casement noted: "We passed for fully 2 hours through the once enormous clearings of the Iguarase Indians. Tizon said they had once been very numerous. There must have been hundreds of them – now none at all. All is desolation."[225]

Entre Rios was bordered by the neighboring section of Atenas, both of these settlements were acquired by Arana's rubber firm prior to 1903. The workforce dedicated to rubber extraction at Entre Rios and Atenas primarily consisted of Huitoto people. Elías Martinengui managed Atenas from 1903 to 1909, during this time period he forced the local indigenous people to constantly work, which left them with little to no time to cultivate their own gardens.[226] Women at Atenas were required to "work" the rubber, which also contributed to the starvation in that area.[160][227][ag] Regarding the Atenas plantation, Roger Casement wrote: "the whole of the population of this district had been systematically starved to death by Elias Martenengui. Martenengui worked his whole district to death, and gave the Indians no time to plant or find food. They had to work rubber or be killed, and to work and die."[228] In 1910, when Casement visited Atenas, records at La Chorrera documented that there were 790 rubber workers at Atenas, however the manager at the time, Alfredo Montt, said he had only "about 250" and three other Peruvian Amazon Company employees under him.[229][ah][ai] The muchachos de confianza oversaw the collection of rubber, and according to Montt, the station brought in 24 tons of rubber annually.[160][aj] In 1911, judge Paredes wrote that Atenas was "peopled by Huitoto spectres" and that there was "a veritable cemetery of skeletons and human skulls scattered along both banks of the Cahuinari, which flows through this district."[231][232][233]

The stations at Abisinia and Matanzas appear most frequently in the reports of abuse collected by Walter Ernest Hardenburg. Both stations were established by Arana's enterprise with the help of Barbadian men around 1904.[234] Many of the Barbadians who were employed by the company at these stations were sent on "commissions" or slave raids.[235] Both Matanzas and Abisinia were inland stations, which meant long marches for natives collecting rubber. Roger Casement referred to them in 1910 as "the two worst stations".[236][237] Matanzas was situated near the Caqueta River and was managed by Armando Normand from 1906 to 1910.[238] According to a 1907 report by Charles C. Eberhardt, who was the American consul in Iquitos, there were approximately 5,000 natives at Matanzas, and 1,600 at Abisinia.[239] In 1910, Normand told Casement he had two fabricos in a year, and his station brought in around 8,500 kg (18,700 lb) for each fabrico. That year, the collection for Matanzas was done by 120 men "working" rubber who collected 140 kg (310 lb) a year. The Abisinia station was situated on a tributary of the Cahuinari River and was managed by Abelardo Agüero from 1905 to 1910. In 1912, it was reported 170 natives remained at Abisinia.[240] Agüero and Normand were both said to have committed innumerable crimes against enslaved indigenous people in their district.[241] They were both dismissed from the company in 1910. At the time, Agüero was in debt to the company for around £500 or £600,[242] while the company owed Normand around £2,100.[243] In 1915, Judge Carlos A. Valcárcel implicated Normand with the destruction of the Cadanechajá, Japaja, Cadanache, Coigaro, Rosecomema, Tomecagaro, Aduije, and Tichuina tribes.[244]

The Rodriguez brothers managed the stations at Santa Catalina and La Sabana between 1904 and 1910;[245] Aurelio Rodriguez managed Santa Catalina and his brother Aristides managed La Sabana.[246] According to Juan A. Tizon, these two were responsible for killing "hundreds of natives"[247][248] and received a 50% commission on the rubber brought into their stations.[248][ak] Barbadian Preston Johnson worked at Santa Catalina for eighteen months, and when asked how many natives he had seen killed there he stated: "a great many". The majority of these killings were carried out because the victim had tried to run away; several others were killed because they were not collecting rubber for the company at the time. Johnson said he knew about natives dying from starvation at La Sabana but he did not know if this was also the case at Santa Catalina.[250] A number of mass killings perpetrated by the Rodriguez brothers were reported in the Hardenburg depositions by Juan Rosas and Genaro Caporo.[251] At Santa Catalina, Aurelio had one of his Barbadian subordinates build a special stockade that was referred to as a "double cepo".[252][253] One part of this cepo restrained the neck and arms, while the other end of the cepo confined the ankles. The piece that restricted the ankles was adjustable, so it could fit a variety of individuals, including children.[254][172][255] Casement stated: "Small boys were often inserted into this receptacle face downwards, and they, as well as grown-up people, women equally with men, were flogged while extended in this posture".[256]

The Resígaro nation inhabited the area between La Sabana and Santa Catalina and those rubber stations were dependent on labor from the Resígaros, as well as Huitoto and Bora nations.[257][258][al] One of the first documented correrías organized by the Rodriguez brothers occurred prior to March 1 of 1903, the expedition targeted a Resígaro maloca, this settlement was ambushed and the survivors were imprisoned.[260] Judge Paredes wrote that by the time of his investigation in 1911, the Resígaro population did "not amount to thirty".[257] He was informed through translators that conflicts with neighboring tribes had been a significant factor in their depopulation. According to Paredes the Resígaros had a "deadly hatred" towards the muchachos de confianza, the Resígaros viewed them to be "[t]heir real enemies", more so than the white colonist.[am] Paredes stated that the muchachos were the first aggressors to be killed during each correria into Resígaro territory, while the Resígaro "never assail[ed]" the white colonists that gave orders to the muchachos.[257] The last female speaker of the Resígaro language, Rosa Andrade, was murdered in 2016,[261] over one hundred years after the nation's first contact with agents of Julio Arana's rubber firm.[an]

The station of Ultimo Retiro, one of the last important stations along the Igaraparaná River, was managed by Alfredo Montt,[ao] and later Augusto Jimenez Seminario. The cepo at Ultimo Retiro was said to have nineteen holes, which were very small. After a demonstration of this cepo, a native told Roger Casement many others had been flogged and starved to death while imprisoned there.[263] Casement later stated this device "was not intended for a place of detention, but for an instrument of torture".[264] In 1910, there was around 25 tons of rubber delivered to La Chorrera from this station.[265] At its height, Ultimo Retiro had 2,000 native workers on its books but by 1912, this workforce had fallen to around 200.[266]

Carlos Miranda managed the section of Sur, which was the closest rubber station to La Chorrera. The route between Sur and La Chorrera could be completed by around 2–3 hours of travel on foot[267] however the indigenous people at Sur travelled "a much greater distance" than this.[268] The judicial commission of 1911 verified the perpetration of many crimes committed at Sur, including several charges levied against Miranda.[269][267][270] One notable crime perpetrated by Miranda was reported in a deposition provided to Roger Casement in 1910. Joseph Labadie, the deponent, claimed that Miranda had ordered an indigenous boy to bring an elderly woman to the station. This woman was brought to Sur with a chain around her neck and she was shot and killed on Miranda's orders. Afterwards, the woman's head was cut off and Miranda presented it to an assembled group of indigenous people, "compulsory witnesses of this tragedy".[271] She had been accused of giving other indigenous people "bad advice", which Casement clarified as advising people against extracting rubber.[125] Miranda informed this group of people that the same fate would befall any "bad Indians".[271][272] Labadie also testified that he had seen "men, women, and children - even little children - flogged at Sur." The end of Labadie's deposition refers to the indigenous population of Sur and states: "they bring in rubber now because if they do not they get flogged and they are frightened ; nothing else - they are flogged only because they don't bring enough rubber to please the 'jefe' of the section."[273]

El Encanto

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2023) |

El Encanto was the most important settlement on the Caraparaná River during the rubber boom. Originally, the settlement belonged to a few Colombians who were known as the Calderon brothers. The Calderon brothers lost their property at Encanto to Arana's company and shortly after, Miguel S. Loayza became the regional manager there. An ex-employee named Carlos Soplín, who swore before a notary, believed the inspector of sections for Encantos "must have flogged over five thousand Indians during the six years he has resided in this region".[274] Soplin also stated in his two-and-a-half months at the Monte Rico section, he witnessed the flagellation of 300 natives, who were flogged between 20 and 200 times if the punishment was intended to kill.[275] According to Soplin, at Esmeraldas, he was witness to the flogging of over 400 natives in three-and-a-half months;[275] these included men, women, children and the elderly, six of whom died from the floggings they received. The plantations of Monte Rico, Argelia, Esperanza, Esmeraldas Indostan, La Florida, and La Sombra delivered their product to El Encanto. Between 1906 and 1907, the population at El Encanto dropped from 2,200, to 1,500 and the explanation provided to the American consul Charles C. Eberhardt stated smallpox had killed around 700 people.[276]

Walter Ernest Hardenburg went to the Putumayo near the end of 1907, shortly after the Peruvian Amazon Company was registered. A group of gunmen working for Loayza arrested Hardenburg and took him to Encanto, where he witnessed the condition of the natives there. He saw people in various stages of sickness and starvation; according to Hardenburg: "These poor wretches, without remedies, without food, were exposed to the burning rays of the vertical sun and the cold rains and heavy dews of early morning until death released them from their sufferings". Their dead bodies were then carried and dumped into the Caraparaná River.[116]

Acquisition of Colombian estates in 1908

[edit]At the beginning of 1908, the Peruvian Amazon Company began a series of attacks against the remaining Colombian patrons in the region, primarily around the Caraparaná River.[ap] These included the settlements of David Serrano, Ordoñez, and Martínez. Ordoñez owned a station called Remolino, which had a portage trail between the Caraparaná and Napo Rivers established on it.[277][aq] Serrano was an important rubber collector on the river who owed money to the Peruvian Amazon Company branch at El Encanto. This debt was previously used as an excuse to send a commission of armed men to Serrano's house to rob him and intimidate him to leave the region.[278] Around 120 Peruvian soldiers were sent from Iquitos to help the Peruvian Amazon Company employees fight against the Colombians. According to Victor Macedo, by 1910, eighty of these soldiers had died, mostly around El Encanto.[279][ar]

The first of these attacks, conversely dated to either January 11 or 12 of 1908, occurred on the Caraparaná River at "La Union", an estate owned by Antonio Ordoñez and Gabriel Martinez. Around eighty-five soldiers from the Peruvian army participated in this attack, they were embarked on gunboat Iquitos and joined by steamship Liberal, which had around eighty armed agents from Arana's company on board.[280][281] At least 5 Colombians were killed at La Union after a fire fight that lasted half of an hour.[282][283] There was around 1,000 arrobas of rubber at the estate which was loaded onto the steamships, the settlement's houses were sacked and burned down afterwards. Several of the Colombian women that lived at La Union were also taken as prisoners on board the two steamships.[284] In a letter dated November 29, 1908, Loayza granted the manager of La Florida authority to assume control over the indigenous workforce that Ordoñez and Martínez had retained.[285]

The Peruvians then travelled to another estate on the Caraparana, La Reserva, which belonged to David Serrano. At the time, there were around 170 arrobas of rubber awaiting exportation from the estate and there was also an abundant supply of Hevea trees in the area.[282] Arroba refers to a unit of weight measurement, one arroba is equal to 15 kilos or 30 pounds. Walter Hardenburg claimed that there were forty five indigenous families dedicated to the extraction of rubber at La Reserva, in January 1908.[286] The Colombian inhabitants of the estate fled from the armed group of Peruvians, later the rubber and other merchandise there was loaded onto the Peruvian steamships, afterwards the settlement was burned down.[282][287] Serrano and many of his companions, with the exception of two men that were taken prisoner, escaped from the first attack on this estate: however Serrano was later captured along with 28 other Colombians by a different group of Peruvians, led by Bartolomé Zumaeta and Miguel Flores in February 1908.[288] Around 23 of those Colombians were employed by the "Gomez & Arana Co"[289] which was recently established in order to exploit the Apaporis River basin.[290] According to three separate depositions collected by Hardenburg, the imprisoned Colombians were tortured by the Peruvians in order to extract information regarding the location of their personal belongings, afterwards the Colombians were killed with bullets and machetes.[288][291][as]

One of the last Colombian patrons victimized by the Peruvian Amazon Company at the beginning of 1908 was Ildefonso Gonzalez, owner of a small estate named "El Dorado" which had around thirty indigenous families there extracting rubber.[293][294] Gonzalez had been active in the rubber industry on the Caraparaná River for around eighteen years by 1908, and like the owners of La Union and La Reserva he refused to sell his property to Arana's Company.[295] Gonzalez was eventually intimidated into abandoned his possession on the Caraparaná River around February 1908.[296][297][298] While he was in the process of transferring his workforce to another estate, at the obligation of Arana's Company, Gonzalez was shot killed by Mariano Olañeta, a chief of section for Arana's company.[297][299] In exchange for Olañeta's service, Miguel S. Loayza appointed him as the manager of Gonzalez's estate and workforce, a position Olañeta retained until his death around April 1909.[297] The indigenous people that extracted rubber for the Colombian patrons of La Union, La Reserva and El Dorado were enslaved by the Peruvian Amazon Company after the acquisition of these estates, including a portion of the Yabuyano nation.[300][289]

Involvement of the Peruvian government and military

[edit]The commander of Peruvian military forces in the Putumayo, Juan Pollack, issued arrest warrants against the agents of Arana's company that participated in the attacks on La Union and Reserva. Peruvian authorities managed to capture those agents, with the notable exception of Bartolome Zumaeta[at] these agents were imprisoned at La Chorrera for two months.[191] Zumaeta fled towards Abisinia at La Chorrera's agency, away from the authorities at El Encanto.[191][155] He was later killed in May 1908 by an indigenous captain named Katenere, whose wife Bartolome had raped.[301] This incident sparked the rebellion of Katenere, which lasted until Katenere was killed in the middle of 1910.[302][303]

Julio César Arana, along with Carlos Rey de Castro and the prefect of Iquitos, Carlos Zapata, travelled together to La Chorrera after the attacks against La Union and La Reserva. Roger Casement believed that "[t]his journey of Senor Arana in company with these two Peruvian officers of high rank is really the key to the whole subsequent situation." Zapata organized the release of the men imprisoned by commander Juan Pollacks orders. Arana was later implicated by British consul David Cazes, Roger Casement and two other sources with bribing prefect Zapata an amount that varies between £5,000 and £8,000 for the release of Arana's imprisoned agents.[191][304]

The owner of the Colombian estate El Pensamiento perished around May 1908 while owing money to Arana's company as well as the British consul general in Iquitos, David Cazes.[305] Arana and Cazes were both under the belief that they had a legal claim to acquire El Pensamiento because the previous owner was indebted to them. Several Huitoto people had fled from Arana's estates in the Putumayo around this time and they arrived at El Pensamiento, which was on the Napo River. According to Cazes these natives were "dreadfully scarred from flogging" and he tried to have them admitted to the courts of Iquitos for evidence in this civil matter; however, the Prefect "Zapata and the Court had these Indians sent away".[306]

Cazes managed to sell all of the rubber collected at El Pensamiento prior to May 1908, when a force of Peruvian soldiers led by Amaedo Burga embarked on the warship Reqeuna and travelled towards El Pensamiento to seize the estate for Arana's company.[307] Burga was the commisario of the Napo River for the Peruvian government, he was also simultaneously employed by Arana's firm as an agent.[308][307][309] An arrest warrant was issued against Cazes by the local court in Iquitos and soldiers were sent to his house, which was also the British consulate in Iquitos. Prefect Zapata delivered an ultimatum to Cazes which was to either surrender his claim on El Pensamiento and pay an £800 fee or face imprisonment. Cazes paid the £800 fee to the court of Iquitos and afterwards commisario Burga imprisoned the Huitoto people that had fled towards El Pensamiento, he then transferred them back towards Arana's estates in the Putumayo.[310] Cazes told Roger Casement that Arana wanted to acquire this estate because it was the best escape route on the Napo River for indigenous people fleeing from oppression on Putumayo River. [311]

Walter Ernest Hardenburg wrote that during his imprisonment on Liberal, he saw the Peruvian comissario of the Putumayo River, César Lúrquin "openly taking with him to Iquitos a little Huitoto girl of some seven years, presumably to sell her as a 'servant'". Regarding Lúrquin, Hardenburg also wrote "instead of stopping on the Putumayo, travelling about there and really making efforts to suppress crime by punishing the criminals, he contented himself with visiting the region four or five times a year—always on the company's launches—stopping a week or so, collecting some children to sell, and then returning and making his 'report.'"[312]

List of reported massacres

[edit]| Year | Date | Location | Description | Reported casualties | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1903 | August 10 | Abisinia | Abelardo Agüero imprisoned 50 natives in stocks without giving them food or water. When the natives started dying, Agüero tied them to a pole and shot them as target practice with his Mauser revolver. | 50 | [313] |

| 1903 | Not clarified[au] | La Chorrera | 30 indigenous people from the Puineses and Renuicueses nations managed to escape from imprisonment at La Chorrera in 1903 while the property was still partially owned by the Larrañaga family. Rafael Larrañaga gathered a group of around subordinate agents along with muchachos de confianza, they pursued the indigenous group that escaped from La Chorrera, which were caught, restrained, then killed with machetes and bullets prior to the bodies being burned[314][av] | 30 | [314][315] |

| 1903 | September 24 | La Chorrera | 25-to-40 Ocaina natives were massacred at La Chorrera when they did not meet the weight quota for rubber. The natives were flogged, burnt alive, and then shot. Judge Carlos A. Válcárcel stated there were 25 victims; a report on slavery in Peru by the US State Department describes the same event, citing 30 natives. Eyewitness Daniel Collantes stated 40 natives while describing the same massacre. | 25-40 | .[316][317] |

| 1903 | Not clarified | Ultimo Retiro | José Inocente Fonseca summoned Chontadura, Ocainama, and Utiguene to Ultimo Retiro. Hundreds of natives appeared. Inocente Fonseca then grabbed his rifle, and with six other employees, massacred 150 native men, women and children. After shooting, Fonseca and other perpetrators of the massacre used machetes on the wounded. The bodies were later burnt. | 150 | [318] |

| 1904 | Not clarified | Abisinia | João Baptista Braga, a Brazilian ex-employee of the Peruvian Amazon Company stated on his arrival at Abisinia, Agüero and Augusto Jiminez had eight natives tied to a pole and murdered. These natives were previously placed in the cepo and were "barbarously martyrised" before their execution, which Agüero used as a demonstration of how the prisoners were treated. | 8 | [319] |

| 1905 | March | Not clarified | João Baptista also described the massacre of 35 natives. Baptista was supposed to kill the captives under orders of Abelardo Agüero but refused to do so. Instead, Agüero ordered Augusto Jimenez to execute the natives. | 35 | [220] |

| 1906 | January | Near the Pamá River,[aw] six hours from the Morelia station | In response to a native drum sounding the signal for help against the caucheros, Augusto Jimenez ordered the execution of around 30 Andoque captives at Abisinia.[ax] | "About 30" | [320] |

| 1906 | Not clarified | Abisinia | At Abisinia, James Mapp and other Barbadians witnessed "about eight" natives being taken to a field one by one, and being shot. Abelardo Agüero, who had just returned to the station from Iquitos, ordered these killings. One of the natives from this group was killed because he was missing a foot, which limited his mobility. | Around 8[ay] | [322] |

| 1906 | "Last days of 1906" | Lower Caqueta River | A group of Colombians made an expedition to the lower Caqueta River with the intention of persuading local natives to extract rubber for them. Twenty Peruvian men armed with rifles attacked the Colombian settlement which was in the process of construction. A group of Peruvian reinforcements led by Armando Normand was sent to help deal with the Colombians. Normand forced the highest-ranking Colombian to tell their boss José de la Paz Gutiérrez to give up all of the weapons he had. According to Roso España, a Colombian who witnessed the event: "Then, in possession of the arms, they began another butchery. The Peruvians discharged their weapons at the Indians who were constructing the roof of the house. These poor unfortunates, pierced by the bullets, some dead, others wounded, rolled off the roof and fell to the ground." The older women were pushed into canoes that were directed into the center of the lake, before they were all shot. According to España: "What they did with the children was still more barbarous, for they jammed them, head-downwards, into the holes that had been dug to receive the posts that were to support the house." Three days later, Normand had the most-senior natives from the captured group clubbed to death. | At least 25 | [323][324] |

| 1907 | "Mid 1907" | Matanzas | Armando Normand killed three elderly natives and two daughters; their bodies were eaten by dogs Normand had trained. | 5 | [325] |

| 1907 | October or November 1907 | Cahuinari | Arístides Rodríguez led a group of fifty men on a correria in an area referred to as Cahuinari. Genaro Caporo, the eyewitness who testified about this event, stated 150 natives were killed by this group, and that th killings were done with rifles and machetes. Afterwards, the group approached and burnt an unknown number of native houses. Caporo's deposition stated there were at least forty families in these houses. | More than 150 | [326] |

| 1910 | May, 1910 | Between the Caqueta River and Morelia | Thirteen natives were killed on a road during an expedition to hunt down the Native Bora chief Katenere, who was rebelling against the company. Barbadian James Chase, who was on the hunt against Katenere, described the events. The expeditioners took prisoner a number of Katenere's supporters and his wife, though Katenere managed to escape when his house was raided. Company agent Fernand Vasquez ordered most of the killings while en route to Morelia, and were carried out by "muchachos de confianza" accompanying him. On the road and near the approach to Morelia, the final three victims – all adult Boras men – were killed; Vasquez shot one and ordered Cherey to shoot the other two because they were too weak from hunger to keep up with the group. James Chase reported a total of thirteen natives were killed during this incident. | 13 | [327] |

The continuance of crime

[edit]Most of the Peruvian Amazon Company's managers in the Putumayo were replaced after Casement's consular commission and judge Paredes's investigation, with the notable exception of Miguel S. Loayza, the general manager of El Encanto. In 1911, the company reported that several of their recently dismissed employees had fled the region, taking up to five hundred indigenous people with them.[328] On November 28 of 1911, the captain of S.S. Liberal allowed around twenty-seven ex-agents of the PAC, many of which had active arrest warrants, to embark on the ship, these men later disembarked in Brazilian territory, away from the influence of Peruvian authorities.[329]

In 1912, lieutenant Aurelio E. O'Donovan of the Peruvian army was arrested for trafficking 12 Huitoto natives onboard steamship Hamburgo, he was transporting them towards Iquitos. This group of 12 natives was composed of eight males and four females, all between the ages of 8 and 14.[330][331]

Fugitive perpetrators

[edit]Abelardo Agüero rallied a group of his subordinates,[az] along with his muchachos de confianza, and set fire to the native crop fields at Abisinia.[333] They took "a large number of Indians with them" [ba] and fled the region, travelling towards the Acre River.[332] A dispatch from English Consul-General Lucien Jerome to the British Foreign Office in 1911 stated the trafficking of natives was carried out with the intention to sell them and to prevent them from providing evidence and testifying to any judicial commission. Jerome also reported that Agüero's group destroyed a Huitoto village.[335][336]

Alfredo Montt and Jose Inocente Fonseca, referred to as two of the "worst Criminals on the Putumayo" by Roger Casement, had managed to flee towards the Javary River with at least 10 Boras people. Montt and Inocente managed to secure employment with a Brazilian firm named Edwards & Serra, the pair had also trafficked around 10 Boras people from the Putumayo, which they were depending on to make money from the Bora's labor.[337] Casement personally pursued the arrest of Montt and Fonseca however he became convinced that these two men had bribed local officials, which facilitated an easy escape away from any authorities seeking to arrest them. The pair managed to evade further arrest attempts made by Peruvian and Brazilian authorities.[337]

In 1914, The Anti-Slavery Reporter and Aborigines' Friend published an article titled "The Putumayo Criminals", which claimed that Victor Macedo was actively travelling around Manaus, the Caqueta River, and the Acre River, with funding for his activities provided by Julio Arana.[338][339] The article noted that Macedo was travelling around with two criminals, previously employed at La Chorrera, named Emilio Mozambite and Fidel Velarde, the latter had been a station manager under Macedo's administration for several years in the Putumayo. The article also claimed that Abelardo Agüero, Augusto Jiménez and Carlos Miranda, the latter was another station manager at La Chorrera, were also located along the Brazil and Bolivia border, where they continued to exploit local indigenous people in the pursuit of rubber extraction.[340][339] In April 1914 Agüero and Jimenez were arrested on an estate belonging to Nicolás Suárez Callaú,[339] however Jimenez managed to escape shortly afterwards.[341] The arresting authorities were under the impression that Macedo had fled shortly before Agüero and Jimenez were captured.[339] Agüero remained incarcerated until at least June 17 of 1916, he filed a writ of Habeas corpus on that date and it eventually led to his release from prison.[341]

Continued exploitation

[edit]The station managers of La Chorrera were replaced by men that were salaried agents of the Peruvian Amazon Company. The most notable of these salaried agents that became managers around 1911 were Cesar Bustamente, Alejandro Vasques Torres, Remigio Vega[bb] and Carlos Seminario.[343][344] The latter of which appears as the primary instigator of a rebellion in oral testimonies that recall events at Santa Catalina from 1916 to 1917.[345][346][347][348] Most stories of indigenous rebellion during this time period acknowledge a common factor as the reason for rebellion, with that factor being the continuance of abuse against the local indigenous population.[349][350][348][bc][351][bd]

Seminario's Ocaina wife and child were killed during the uprising at Santa Catalina.[348][352][350] Soldiers from the Peruvian army attacked the indigenous people at Santa Catalina as a reprisal for the mutiny against Seminario.[be] According to Nancy Ochoa and several other oral testimonies, the indigenous rebels fortified themselves inside of a maloca, however this maloca was burned and destroyed by the soldiers.[348][354][bf] As part of a series of forced emigrations from the Putumayo River basin, Seminario took the remaining indigenous people from his district of Santa Catalina to Providencia, a settlement on the Igaraparana river. S.S. Liberal later took members from the Aguaje nation at Providencia and transported them towards Remanso, years later, these indigenous people were forced by the Loayza brothers to relocate again, this time towards the mouth of the Algodon River.[356]

There was a separate rebellion at Atenas during this time period, which was written about by an Irish missionary named Leo Sambrook, a Capuchin friar named Gaspar de Pinell and documented later by anthropologist examining oral histories.[349][357][358] Gaspar de Pinell wrote that an indigenous uprising occurred against Arana's company on the Igaraparana in 1917 and a company of Peruvian soldiers were sent to the region to suppress the mutiny. Pinell was able to gain access to a census conducted by Arana's company that year, that document claimed that there were 2,300 indigenous people dedicating to extracting rubber on the Caraparaná River while there were around 6,200 people on the Igaraparaná River working for Arana's company.[357] Sambrook noted that physical abuse against the local indigenous people continued and this rebellion consisted of around 900 indigenous men, mostly Boras. Peruvian soldiers were sent to this area to suppress the rebellion and in Sambrook's account the Atenas area was recaptured, indigenous houses were burned down and the survivors were rounded up.[349] Pinell and Sambrook both noted that some of the Peruvian soldiers were armed with machine guns.[359][360] Researcher and author Jordan Goodman suggested that this rebellion at Atenas may be the same incident as the "rebellion of Yarocamena", which also originated at Atenas.[361]

Anthropologist Benjamín Yépez examined the oral history of Yarocamena's rebellion and he concluded that this incident probably coincided with the mutiny of 1917 which Pinell wrote about. He did acknowledge that "it is difficult to pinpoint the date of the movement." Yépez wrote that the story of Yarocamena "shows the course of an action that ended in the genocide of almost all the Witotos who rebelled in the Atenas maloca."[362] Three of the oral testimonies documented by Yépez noted that several white men were killed by the rebels prior to the local indigenous people fortifying Atenas. A tunnel was dug under the maloca of Atenas and the indigenous people placed rubber bales around the settlement to provide protection from bullets. The white owners of Atenas returned after an unspecified length of time, armed and accompanied by Peruvian soldiers as well as muchachos de confianza. According to two oral testimonies collected by Yépez, the Peruvian soldiers burned the maloca, the indigenous people that had survived the fire by hiding in the tunnel beneath the maloca were subsequently executed by the Peruvian soldiers. Javier Witoto, one of the sources of this information, noted that the few remaining indigenous people continued to extract rubber for the white colonist.[363]

According to Carlos Loayza, the brother of Miguel S. Loayza, between 1924 and 1930, a population of at least 6,719 indigenous people, from La Chorrera's agency, was forced to emigrate from their traditional territory in the Putumayo River basin and relocate towards the Ampyiacu-Yahuasyacu River basins, which was deeper into Peruvian territory.[364] At the time, the Loayza family owned the rights to minerals and lumber in a large area covering the Ampiyacu-Yahuasyacu watersheds.[365] Loayza Carlos stated that around half of the indigenous population relocated by the Loayza's perished from measles after the forced migrations were finished.[364] These diseases were primarily spread during the transportation of supplies for the Peruvian army at Puerto Arturo, during the time of the Colombian-Peruvian war. Carlos also wrote that there were nations from El Encanto's agency that were completely annihilated from the measles epidemic.[366] Jean Patrick Razon, who published a short history on the Bora people, also noted that these forced migrations took place over the course of seven years, 1924-1930 and "more than half of this displaced group perished before reaching their final destination." Cultural anthropologist Eduardo Javier Romero Dianderas wrote that in this context "the contemporary presence of Bora, Huitoto and Ocaina populations in Ampiyacu basin is in itself an outcome of the violence exercised by extractive capital upon indigenous peoples of Amazonia"[367] Wesley Thiesen, who lived with the Boras people in Peru and worked the Summer Institute of Linguistics International, noted that the Bora population was exploited by the Loayza's under the "patrón system" for around forty years after their migration in Peru.[368]

| SECTIONS | Males | Females | Children (females) | Children (males) | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abisinia (Boras) | 167 | 180 | 120 | 73 | 540 |

| Sta. Catalina (Boras) | 245 | 212 | 125 | 84 | 666 |

| Sur (Witotos) | 169 | 155 | 168 | 103 | 595 |

| Ultimo Retiro (Witotos) | ? | 116 | 105 | 66 | 383[bg] |

| Entre Rios (Witotos) | 373 | 380 | 266 | 219 | 1,238 |

| Occidente (Witotos) | 454 | 385 | 199 | 180 | 1,218 |

| Andokes (Andokes) | 127 | 105 | 64 | 65 | 361 |

| Sabana (Muinanes) | 255 | 237 | 113 | 94 | 699 |

| Oriente (Ocaina) | 318 | 257 | 125 | 108 | 808 |

| Chorrera | 80 | 54 | 50 | 27 | 211 |

| TOTAL | 2,284 | 2,081 | 1,335 | 1,019 | 6,719 |

In popular culture

[edit]- The Dream of the Celt by Mario Vargas Llosa details some of Irishman Roger Casement's experiences in investigating the Putumayo genocide.

- Terence McKenna's travelogue True Hallucinations take place in an area affected by the Putumayo genocide, and discusses the history

- The novel The Vortex by José Eustasio Rivera is based on the events, which are portrayed through the narration of Don Clemente Silva.

- The film Embrace of the Serpent, which was directed by Ciro Guerra, includes characters who are affected by the Putumayo genocide.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Prior to the rubber boom, Cinchona and Smilax officinalis (Sarsapilla) were the most-profitable extractive industries in the Amazonian basins of Colombia and Peru. Sarsapilla can be used as a treatment for psoriasis, and quinine was a treatment for malaria and yellow fever.[7]

- ^ The Aimenes natives are cited as the first nation to become subjugated at La Chorrera.[24][25]

- ^ Larrañaga sought to attract investment into his rubber firm, however most of the merchants in Pará refused to associate with him, with the exception of José Maria Mori and Jacobo Barchillón. These two men provided Larrañaga with the funding to purchase the merchandize required to continue operating his enterprise.[22] Barchillón later became a business partner in Larrañaga's firm and he was also implicated in two separate massacres that occurred near La Chorrera in 1903.[26]

- ^ The Muinane and Nonuyas nations traditional territory was around the Entre Rios, Atenas, La Sabana and Matanzas areas.[29][30] The first indigenous people captured in the slave raids sent out from Matanzas were from the Muinane nation.[31]

- ^ The Calderón Hermanos were originally the owners of El Encanto.[34][35] In the words of the Peruvian judge which in 1911 investigated crime in the region, the establishment of this settlement on the Cara Paraná River signaled "another conquest of fresh Indians."[28] These indigenous populations were divided between the Colombian patrons in the area and thereafter they began extracting rubber for these Colombians.[28]

- ^ "All native joy died in these woods when these half-castes imposed themselves upon this primitive people, and, in place of occasional raid and inter-tribal fight, gave them the bullet, the lash, the cepo, the chain gang, and death by hunger, death by blows, death by twenty forms of organinsed murder." - Roger Casement[37]