Rationale for the Iraq War

There are various rationales for the Iraq War that have been used to justify the 2003 invasion of Iraq and subsequent hostilities.

The George W. Bush administration began actively pressing for military intervention in Iraq in late 2001. The primary rationalization for the Iraq War was articulated by a joint resolution of the United States Congress known as the Iraq Resolution. The United States intent was to "disarm Iraq of weapons of mass destruction, to end Saddam Hussein's support for terrorism, and to free the Iraqi people".[1]

In the lead-up to the invasion, the United States and the United Kingdom falsely claimed that Saddam Hussein was developing weapons of mass destruction, covertly supporting al-Qaeda and that he presented a threat to Iraq's neighbors and to the world community. According to U.S.-based investigative journalist organization Center for Public Integrity, eight senior-level officials in the Bush administration issued at least 935 false statements in the two years leading up to the war.[2] The US stated, "On November 8, 2002; the UN Security Council unanimously adopted Resolution 1441. All 15 members of the Security Council agreed to give Iraq a final opportunity to comply with its obligations and disarm or face the serious consequences of failing to disarm. The resolution strengthened the mandate of the UN Monitoring and Verification Commission (UNMOVIC) and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), giving them the authority to go anywhere, at any time, and talk to anyone in order to verify Iraq's disarmament."[3]

Throughout late 2001, 2002, and early 2003, the Bush administration worked to build a case for invading Iraq, culminating in then-Secretary of State Colin Powell's February 2003 address to the Security Council.[4] Shortly after the invasion, the Central Intelligence Agency, Defense Intelligence Agency, and other intelligence agencies largely discredited evidence related to Iraqi weapons as well as alleged links to al-Qaeda, and at this point, the Bush and Blair administrations began to shift to secondary rationales for the war, such as the Saddam Hussein government's human rights record and promoting democracy in Iraq.[5][6]

Opinion polls showed that people of nearly all countries opposed a war without a UN mandate and that the perception of the United States as a danger to world peace had significantly increased.[7] UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan described the war as illegal, saying in a September 2004 interview that it was "not in conformity with the Security Council".[8] The US led the effort for "the redirection of former Iraqi weapons of mass destruction (WMD) scientists, technicians, and engineers to civilian employment and discourage emigration of this community from Iraq".[9]

The US officially declared its combat role in Iraq over on 31 August 2010, although several thousand troops remained in the country until all American troops were withdrawn from Iraq by December 2011; meanwhile, American troops also engaged in combat with Iraqi insurgents. In June 2014, US forces returned to Iraq due to an escalation of instability in the region, and in June 2015 the number of American ground troops totaled 3,550. Between December 2011 and June 2014, Department of Defense officials estimated that there were 200 to 300 personnel based at the US embassy in Baghdad.[10]

Background

[edit]The Gulf War never ended officially because there was no armistice to formally end it. As a result, relations between the United States, the United Nations, and Iraq remained strained, although Saddam Hussein issued formal statements renouncing his invasion of Kuwait and made reparations payments. The US and the United Nations maintained a policy of "containment" towards Iraq, which involved economic sanctions, Iraqi no-fly zones enforced by the United States, United Kingdom, and France (until it ended its no-fly zone operations in 1998) and ongoing inspections of Iraqi weapons programs.[11] In 2002, the UN Security Council unanimously passed Resolution 1441 demanding that Iraq "comply with its disarmament obligations" and allow weapons inspections. Iraq war critics such as former weapons inspector Scott Ritter claimed that these sanctions and weapons inspections policies, supported by both the Bush and Clinton administrations, were actually intended to foster regime change in Iraq.[12]

US policy shifted in 1998 when the United States Congress passed and President Bill Clinton signed the Iraq Liberation Act after Iraq terminated its cooperation with UN weapons inspectors the preceding August. The act made it official US policy to "support efforts to remove the regime headed by Saddam Hussein from power", although it also made clear that "nothing in this Act shall be construed to authorize or otherwise speak to the use of United States Armed Forces".[13][14] This legislation contrasted with the terms set out in United Nations Security Council Resolution 687, which made no mention of regime change.[15]

One month after the passage of the "Iraq Liberation Act", the US and UK launched a bombardment of Iraq named Operation Desert Fox. The campaign's expressed rationale was to hamper the Saddam Hussein government's ability to produce chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons, but US national security personnel also reportedly hoped it would help weaken Saddam Hussein's grip on power.[16]

The Republican Party's campaign platform in the 2000 election called for "full implementation" of the Iraq Liberation Act and removal of Saddam Hussein; and key Bush advisers, including Vice President Dick Cheney, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, and Rumsfeld's Deputy Paul Wolfowitz, were longstanding advocates of invading Iraq, and contributed to a September 2000 report from the Project for the New American Century that argued for using an invasion of Iraq as a means for the US to "play a more permanent role in Gulf regional security".[17] After leaving the administration, former Bush treasury secretary Paul O'Neill said that "contingency planning" for an attack on Iraq had been planned since the inauguration and that the first National Security Council meeting discussed of an invasion.[18] Retired Army General Hugh Shelton, former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said he saw nothing to indicate the United States was close to attacking Iraq early in Bush's term.[18]

Despite key Bush advisers' stated interest in invading Iraq, little formal movement towards an invasion occurred until the 11 September 2001 attacks. According to aides who were with Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld in the National Military Command Center on 11 September, Rumsfeld asked for: "best info fast. Judge whether good enough hit Saddam Hussein at same time. Not only Osama bin Laden."[19]

In the days immediately following 9/11, the Bush administration national security team actively debated an invasion of Iraq. A memo written by Secretary Rumsfeld dated 27 November 2001 considers a US–Iraq war. One section of the memo lists multiple possible justifications for a US–Iraq War.[20] That administration opted instead to limit the initial military response to Afghanistan.[21] President Bush began laying the public groundwork for an invasion of Iraq in a January 2002 State of the Union address, calling Iraq a member of the Axis of Evil and saying "The United States of America will not permit the world's most dangerous regimes to threaten us with the world's most destructive weapons."[22] Over the next year, the Bush administration began pushing for international support for an invasion of Iraq, a campaign that culminated in Secretary of State Colin Powell's 5 February 2003 presentation to the United Nations Security Council.[23][24] However, a 5 September 2002 report from Major General Glen Shaffer revealed that the Joint Chiefs of Staff's J2 Intelligence Directorate had concluded that the United States' knowledge on different aspects of the Iraqi WMD program ranged from essentially zero to about 75%, and that knowledge was particularly weak on aspects of a possible nuclear weapons program: "Our knowledge of the Iraqi nuclear weapons program is based largely – perhaps 90% – on analysis of imprecise intelligence", they concluded;[clarification needed] "Our assessments rely heavily on analytic assumptions and judgment rather than hard evidence. The evidentiary base is particularly sparse for Iraqi nuclear programs."[25][26]

After failing to gain UN support for an additional UN authorization, the US, together with the UK and small contingents from Australia, Poland, and Denmark, launched an invasion on 20 March 2003 under the authority of UN Security Council Resolution 660 and United Nations Security Council Resolution 678.[11] A 2008 study conducted by two investigative journalism organizations (Center for Public Integrity and Foundation for Independent Journalism) revealed that between September 2001 and September 2003, George W. Bush and seven senior officials in his administration issued explicit statements on at least 532 occasions claiming that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction or had established covert alliances with al-Qaeda, or both.[27][28][29] The study concluded that such statements were issued by the American government as part of an "orchestrated campaign" to generate jingoistic attitudes in the United States in order to initiate a war based on "false pretenses".[30][31]

Iraq War Resolution

[edit]

In its Iraq War Resolution issued on October 2002, the U.S. congress articulated several allegations as part of its attempts to build justification for the invasion of Iraq:[32]

- Iraq's noncompliance with the conditions of the 1991 ceasefire agreement, including interference with UN weapons inspectors.

- Iraq's alleged weapons of mass destruction, and programs to develop such weapons, posed a "threat to the national security of the United States and international peace and security in the Persian Gulf region".

- Iraq's "brutal repression of its civilian population".

- Iraq's "capability and willingness to use weapons of mass destruction against other nations and its own people".

- Iraq's hostility towards the United States as demonstrated by the 1993 assassination attempt on former President George H. W. Bush and firing on coalition aircraft enforcing the no-fly zones following the 1991 Gulf War.

- Members of al-Qaeda, an organization bearing responsibility for attacks on the United States, its citizens, and interests, including the attacks that occurred on 11 September 2001, are known to be in Iraq.

- Iraq's "continuing to aid and harbor other international terrorist organizations", including anti-United States terrorist organizations.

- Iraq's alleged plans to launch attacks against United States using weapons of mass destruction.

- Iraq's alleged plans to transfer weapons of mass destruction to terrorist organizations.

- Iraq paid bounty to families of suicide bombers.

- The efforts by the Congress and the President to fight terrorists, including the 11 September 2001 terrorists and those who aided or harbored them.

- The authorization by the Constitution and the Congress for the President to fight anti-United States terrorism.

- The governments in Turkey, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia feared Saddam and wanted him removed from power.

- Citing the Iraq Liberation Act of 1998, the resolution reiterated that it should be the policy of the United States to remove the Saddam Hussein regime and promote a democratic replacement.

The Resolution required President Bush's diplomatic efforts at the UN Security Council to "obtain prompt and decisive action by the Security Council to ensure that Iraq abandons its strategy of delay, evasion, and noncompliance and promptly and strictly complies with all relevant Security Council resolutions". It authorized the United States to use military force to "defend the national security of the United States against the continuing threat posed by Iraq; and enforce all relevant United Nations Security Council Resolutions regarding Iraq".

Weapons of mass destruction

[edit]

The US government's belief that Iraq was developing weapons of mass destruction (WMDs), was based upon documents which the CIA argued could not be trusted.[33]

George Bush, speaking in October 2002, said that "The stated policy of the United States is regime change … However, if [Saddam Hussein] were to meet all the conditions of the United Nations, the conditions that I have described very clearly in terms that everybody can understand, that in itself will signal the regime has changed."[34] Similarly, in September 2002, Tony Blair stated, in an answer to a parliamentary question, that "Regime change in Iraq would be a wonderful thing. That is not the purpose of our action; our purpose is to disarm Iraq of weapons of mass destruction".[35] In November of that year, Tony Blair further stated that "So far as our objective, it is disarmament, not regime change – that is our objective. Now I happen to believe the regime of Saddam is a very brutal and repressive regime; I think it does enormous damage to the Iraqi people … so I have got no doubt Saddam is very bad for Iraq, but on the other hand I have got no doubt either that the purpose of our challenge from the United Nations is disarmament of weapons of mass destruction; it is not regime change."[36]

Between September 2002 and May 2003, Bush administration began attempting to mix its "war on terror" rhetoric with weapons of mass destruction allegations, in addition to espousing allegations of Iraqi support to al-Qaeda.[37] In his 2003 State of the Union address delivered on 28 January 2003, George W. Bush insinuated about hypothetical scenarios wherein Ba'athist Iraq was plotting to perpetrate mass-casualty attacks using chemical weapons:

"Before September the 11, many in the world believed that Saddam Hussein could be contained. But chemical agents, lethal viruses and shadowy terrorist networks are not easily contained. Imagine those 19 hijackers with other weapons and other plans— this time armed by Saddam Hussein. It would take one vial, one canister, one crate slipped into this country to bring a day of horror like none we have ever known. We will do everything in our power to make sure that that day never comes."[38]

At a press conference on January 31, 2003, George Bush stated: "Saddam Hussein must understand that if he does not disarm, for the sake of peace, we, along with others, will go disarm Saddam Hussein."[39] As late as 25 February 2003, Tony Blair said in the House of Commons: "I detest his regime. But even now he can save it by complying with the UN's demand. Even now, we are prepared to go the extra step to achieve disarmament peacefully."[40]

Secretary of State Powell said in his 5 February 2003 presentation to the UN Security Council:

"the facts and Iraq's behavior show that Saddam Hussein and his regime are concealing their efforts to produce more weapons of mass destruction".[41]

During the same presentation, Powell also claimed that al-Qaeda was attempting to build weapons of mass destruction with Iraqi support:

"Al-Qaida continues to have a deep interest in acquiring weapons of mass destruction. As with the story of Zarqawi and his network, I can trace the story of a senior terrorist operative telling how Iraq provided training in these weapons to al-Qaida. Fortunately, this operative is now detained and he has told his story. ... The support that this detainee describes included Iraq offering chemical or biological weapons training for two al-Qaida associates beginning in December 2000. He says that a militant known as Abdallah al-Iraqi had been sent to Iraq several times between 1997 and 2000 for help in acquiring poisons and gasses. Abdallah al-Iraqi characterized the relationship he forged with Iraqi officials as successful."

— Colin Powell's presentation to the UN Security Council, 5 February 2003, [42]

On 11 February 2003, FBI Director Robert Mueller testified to Congress that "Iraq has moved to the top of my list. As we previously briefed this Committee, Iraq's weapons of mass destruction program poses a clear threat to our national security, a threat that will certainly increase in the event of future military action against Iraq. Baghdad has the capability and, we presume, the will to use biological, chemical, or radiological weapons against US domestic targets in the event of a US invasion."[43][44] In a radio speech delivered on 8 March 2003, George W. Bush said:

“The attacks of September 11, 2001 showed what the enemies of America did with four airplanes. We will not wait to see what terrorists or terror states could do with weapons of mass destruction.”[45]

On 10 April 2003, White House press secretary Ari Fleischer reiterated that, "But make no mistake – as I said earlier – we have high confidence that they have weapons of mass destruction. That is what this war was about and it is about. And we have high confidence it will be found."[46] Despite the Bush administration's consistent assertion that Iraqi weapons programs justified an invasion, former Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz later cast doubt on the administration's conviction behind this rationale by saying in a May 2003 interview: "For bureaucratic reasons, we settled on one issue – weapons of mass destruction – because it was the one reason everyone could agree on."[47]

After the invasion, despite an exhaustive search led by the Iraq Survey Group involving a more than 1,400 member team, no evidence of Iraqi weapons programs was found. On the contrary, the investigation concluded that Iraq had destroyed all major stockpiles of weapons of mass destruction and ceased production in 1991 when sanctions were imposed.[48][49][50] The failure to find evidence of Iraqi weapons programs following the invasion led to considerable controversy in the United States and worldwide, including claims by critics of the war that the Bush and Blair administrations deliberately manipulated and misused intelligence to push for an invasion.

UN inspections before the invasion

[edit]Between 1991 and 1998, the United Nations Security Council tasked the United Nations Special Commission on Disarmament (UNSCOM) with finding and destroying Iraq's weapons of mass destruction. In 1996, UNSCOM discovered evidence of continued biological weapons research and supervised destruction of the Al Hakum biological weapons production site – allegedly converted to a chicken feed plant, but retaining its barbed wire fences and anti-aircraft defenses.[51][52] In 1998, Scott Ritter, leader of a UNSCOM inspection team, found gaps in the prisoner records of Abu Ghraib when investigating allegations that prisoners had been used to test anthrax weapons. Asked to explain the missing documents, the Iraqi government charged that Ritter was working for the CIA and refused to cooperate further with UNSCOM.

On August 26, 1998, approximately two months before the US ordered United Nations inspectors withdrawn from Iraq, Scott Ritter resigned from his position rather than participate in what he called the "illusion of arms control". In his resignation letter to Ambassador Richard Butler,[53] Ritter wrote:

"The sad truth is that Iraq today is not disarmed. ... UNSCOM has good reason to believe that there are significant numbers of proscribed weapons and related components and the means to manufacture such weapons unaccounted for in Iraq today … Iraq has lied to the Special Commission and the world since day one concerning the true scope and nature of its proscribed programs and weapons systems."

On September 7, 1998, Ritter testified before the Senate Armed Services and Foreign Relations Committee,[54] and John McCain (R, AZ) asked him whether UNSCOM had intelligence suggesting that Iraq had assembled the components for three nuclear weapons and all that it lacked was the fissile material. Ritter replied: "The Special Commission has intelligence information, which suggests that components necessary for three nuclear weapons exists, lacking the fissile material. Yes, sir."

On 8 November 2002, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1441, giving Iraq "a final opportunity to comply with its disarmament obligations" including unrestricted inspections by the United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission (UNMOVIC) and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Saddam Hussein accepted the resolution on November 13 and inspectors returned to Iraq under the direction of UNMOVIC chairman Hans Blix and IAEA Director General Mohamed ElBaradei. Between that time and the time of the invasion, the IAEA "found no evidence or plausible indication of the revival of a nuclear weapons programme in Iraq"; the IAEA concluded that certain items which could have been used in nuclear enrichment – centrifuges, such as aluminum tubes, were in fact intended for other uses.[55] UNMOVIC "did not find evidence of the continuation or resumption of programmes of weapons of mass destruction" or significant quantities of proscribed items. UNMOVIC did supervise the destruction of a small number of empty chemical rocket warheads, 50 liters of mustard gas that had been declared by Iraq and sealed by UNSCOM in 1998, and laboratory quantities of a mustard gas precursor, along with about 50 Al-Samoud missiles of a design that Iraq claimed did not exceed the permitted 150 km range, but which had traveled up to 183 km in tests. Shortly before the invasion, UNMOVIC stated that it would take "months" to verify Iraqi compliance with resolution 1441.[56][57][58]

Formal search after the invasion

[edit]After the invasion, the Iraq Survey Group (ISG), headed by American David Kay, was tasked with searching for weapons of mass destruction. The survey ultimately concluded that Iraqi production of weapons of mass destruction ceased and all major stockpiles were destroyed in 1991 when economic sanctions were imposed, but that the expertise to restart production once sanctions were lifted was preserved. The group also concluded that Iraq continued developing long-range missiles proscribed by the UN until just before the 2003 invasion.[citation needed]

In an interim report on 3 October 2003, Kay reported that the group had "not yet found stocks of weapons", but had discovered "dozens of weapons of mass destruction-related program activities" including clandestine laboratories "suitable for continuing CBW [chemical and biological warfare] research", a prison laboratory complex "possibly used in human testing of BW agents", a vial of live C. botulinum Okra B bacteria kept in one scientist's home, small parts and twelve-year-old documents "that would have been useful in resuming uranium enrichment", partially-declared UAVs and undeclared fuel for Scud missiles with ranges beyond the 150 km UN limits, "[p]lans and advanced design work for new long-range missiles with ranges up to at least 1000 km", attempts to acquire long-range missile technology from North Korea, and document destruction in headquarters buildings in Baghdad. None of the weapons of mass destruction programs involved active production; they instead appeared to be targeted at retaining the expertise needed to resume work once sanctions were dropped. Iraqi personnel involved with much of this work indicated they had orders to conceal it from UN weapons inspectors.[59][60]

After Charles Duelfer took over from Kay in January 2004, Kay said at a Senate hearing that "we were almost all wrong" about Iraq having stockpiles of weapons of mass destruction, but that the other ISG findings made Iraq potentially "more dangerous" than was thought before the war.[61][62] In an interview, Kay said that "a lot" of the former Iraqi government's weapons of mass destruction program had been moved to Syria shortly before the 2003 invasion, albeit not including large stockpiles of weapons.[63]

On 30 September 2004, the ISG, under Charles Duelfer, issued a comprehensive report. The report stated that "Iraq's weapons of mass destruction capability ... was essentially destroyed in 1991" and that Saddam Hussein subsequently focused on ending the sanctions and "preserving the capability to reconstitute his weapons of mass destruction (WMD) when sanctions were lifted". No evidence was found for continued active production of weapons of mass destruction subsequent to the imposition of sanctions in 1991, though "[b]y 2000–2001, Saddam had managed to mitigate many of the effects of sanctions".[64]

The report concluded in its Key Findings that: "Saddam [Hussein] so dominated the Iraqi Regime that its strategic intent was his alone ... The former Regime had no formal written strategy or plan for the revival of weapons of mass destruction after sanctions. Neither was there an identifiable group of weapons of mass destruction policy makers or planners separate from Saddam. Instead, his lieutenants understood weapons of mass destruction revival was his goal from their long association with Saddam and his infrequent, but firm, verbal comments and directions to them." The report also noted that "Iran was the pre-eminent motivator of [Iraq's weapons of mass destruction revival] policy. ... The wish to balance Israel and acquire status and influence in the Arab world were also considerations, but secondary." A March 2005 addendum to the report stated that "based on the evidence available at present, ISG judged that it was unlikely that an official transfer of weapons of mass destruction material from Iraq to Syria took place. However, ISG was unable to rule out unofficial movement of limited weapons of mass destruction-related materials".[49][65]

On 12 January 2005, US military forces abandoned the formal search. Transcripts from high level meetings within Saddam Hussein's government before the invasion are consistent with the ISG conclusion that he destroyed his stockpiles of weapons of mass destruction but maintained the expertise to restart production.[66]

Discovery of chemical weapons

[edit]In the post-invasion search for weapons of mass destruction, US and Polish forces found decayed chemical weapons from the Iran–Iraq War. These chemical weapons led former senator Rick Santorum (R-PA) and representative Peter Hoekstra (R-MI) to say that the US had indeed found weapons of mass destruction in Iraq.[50]

These assertions were directly contradicted by weapons experts David Kay, the original director of the Iraq Survey Group, and his successor Charles Duelfer. Both Kay and Duelfer stated that the chemical weapons found were not the "weapons of mass destruction" that the US was looking for. Kay added that experts on Iraq's chemical weapons are in "almost 100 percent agreement" that sarin nerve agent produced in the 1980s would no longer be dangerous and that the chemical weapons found were "less toxic than most things that Americans have under their kitchen sink at this point". In reply, Hoekstra said "I am 100 percent sure if David Kay had the opportunity to look at the reports ... he would agree ... these things are lethal and deadly".[67] Discussing the findings on NPR's Talk of the Nation, Charles Duelfer described such residual chemical munitions as hazardous but not deadly.

What we found, both as UN and later when I was with the Iraq Survey Group, is that some of these rounds would have highly degraded agent, but it is still dangerous. You know, it can be a local hazard. If an insurgent got it and wanted to create a local hazard, it could be exploded. When I was running the ISG – the Iraq Survey Group – we had a couple of them that had been turned into these IEDs, the improvised explosive devices. But they are local hazards. They are not a major, you know, weapon of mass destruction.[68]

The degraded chemical weapons were first discovered in May 2004, when a binary sarin nerve gas shell was used in an improvised explosive device (roadside bomb) in Iraq. The device exploded before it could be disarmed, and two soldiers displayed symptoms of minor sarin exposure. The 155 mm shell was unmarked and rigged as if it were a normal high-explosive shell, indicating that the insurgents who placed the device did not know it contained nerve gas. Earlier in the month, a shell containing mustard gas was found abandoned in the median of a road in Baghdad.[69][unreliable source?][70]

In July 2004, Polish troops discovered insurgents trying to purchase cyclosarin, an extremely toxic substance which is an organophosphate nerve agent like its predecessor, sarin, in gas warheads produced during the Iran–Iraq War. To thwart these insurgents, Polish troops purchased two rockets on 23 June 2004. The US military later determined that the two rockets had only traces of sarin, small and deteriorated and virtually harmless, with "limited to no impact if used by insurgents against coalition forces".[71]

'Dodgy dossier'

[edit]The Dodgy Dossier was an article written by Ibrahim al-Marashi which was plagiarized by the British government in a 2003 briefing document entitled Iraq: Its Infrastructure of Concealment, Deception and Intimidation.[72][73] This document was a follow-up to the earlier September Dossier, both of which concerned Iraq and weapons of mass destruction and were ultimately used by the government to justify its involvement in the 2003 Invasion of Iraq. Large portions of al-Marashi's paper were quoted verbatim by the United States Secretary of State Colin Powell to the UN General Assembly. The most frequently quoted section was the allegation that Saddam had WMDs that could be launched within 45 minutes.

The material plagiarized from Marashi's work and copied nearly verbatim into the "Dodgy Dossier" was six paragraphs from his article Iraq's Security & Intelligence Network: A Guide & Analysis,[74] which was published in the September 2002 issue[75] of the Middle East Review of International Affairs (or MERIA). Tony Blair's office ultimately apologized to Marashi for its actions, but not to the MERIA journal.[76][77]

Conclusions

[edit]The bad news, therefore, is that the UN proved unequal to the task of preventing a rogue regime from stealing some of its own money. The good news is that this same UN machinery proved equal to the task of preventing that same regime from fielding WMD, developing nuclear weapons and reconstituting a military threat to its neighbors. Most observers would conclude that the UN, however inadequate its financial oversight, certainly got its priorities right.

The UN sanctions regime against Iraq, including the Oil for Food program is worth close scrutiny not because it was a scandal, although scandal there was, but because taken as a whole, it is the most successful use of international sanctions on record. Documenting the why and wherefores of that success is as important as correcting the shortfalls that allowed a rogue regime, in connivance with unscrupulous international businessmen, to siphon funds from UN-administered Iraqi accounts.[78]

The failure to find stockpiles of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq caused considerable controversy, particularly in the United States. US President George W. Bush and Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Tony Blair defended their decision to go to war, alleging that many nations, even those opposed to war, believed that the Saddam Hussein government was actively developing weapons of mass destructions.[citation needed]

Critics such as Democratic National Committee Chairman Howard Dean charged that the Bush and Blair administrations deliberately falsified evidence to build a case for war.[79] These criticisms were strengthened with the 2005 release of the so-called Downing Street memo, written in July 2002, in which the former head of British Military Intelligence wrote that "the intelligence and facts were being fixed around the policy" of removing Saddam Hussein from power.[80]

While the Downing Street memo and the yellowcake uranium scandal lent credence to claims that intelligence was manipulated, two bipartisan investigations, one by the Senate Intelligence Committee and the other by a specially-appointed Iraq Intelligence Commission chaired by Charles Robb and Laurence Silberman, found no evidence of political pressure applied to intelligence analysts.[81] An independent assessment by the Annenberg Public Policy Center found that Bush administration officials did misuse intelligence in their public communications. For example, Vice President Dick Cheney's September 2002 statement on Meet the Press that "we do know, with absolute certainty, that he (Saddam) is using his procurement system to acquire the equipment he needs in order to enrich uranium to build a nuclear weapon", was inconsistent with the views of the intelligence community at the time.[81]

A study co-authored by the Center for Public Integrity found that in the two years after September 11, 2001, the president and top administration officials had made 935 false statements, in an orchestrated public relations campaign to galvanize public opinion for the war, and that the press was largely complicit in its uncritical coverage of the reasons adduced for going to war.[82][83] PBS commentator Bill Moyers had made similar points throughout the lead-up to the Iraq War, and prior to a national press conference on the Iraq War[84] Moyers correctly predicted "at least a dozen times during this press conference he [the President] will invoke 9/11 and al-Qaeda to justify a preemptive attack on a country that has not attacked America. But the White House press corps will ask no hard questions tonight about those claims."[85][86] Moyers later also denounced the complicity of the press in the administration's campaign for the war, saying that the media "surrendered its independence and skepticism to join with [the US] government in marching to war", and that the administration "needed a compliant press, to pass on their propaganda as news and cheer them on".[86]

Many in the intelligence community expressed sincere regret over the flawed predictions about Iraqi weapons programs. Testifying before Congress in January 2004, David Kay, the original director of the Iraq Survey Group, said unequivocally that "It turns out that we were all wrong, probably in my judgment, and that is most disturbing."[87] He later added in an interview that the intelligence community owed the President an apology.[88]

In the aftermath of the invasion, much attention was also paid to the role of the press in promoting government claims concerning weapons of mass destruction production in Iraq. Between 1998 and 2003, The New York Times and other influential US newspapers published numerous articles about suspected Iraqi rearmament programs with headlines like "Iraqi Work Toward A-Bomb Reported" and "Iraq Suspected of Secret Germ War Effort". It later turned out that many of the sources for these articles were unreliable, and that some were tied to Ahmed Chalabi, an Iraqi exile with close ties to the Bush administration who was a consistent supporter of an invasion.[89][90][91]

Some controversy also exists regarding whether the invasion increased or decreased the potential for nuclear proliferation. For example, hundreds of tons of dual-use high explosives that could be used to detonate fissile material in a nuclear weapon were sealed by the IAEA at the Al Qa'qaa site in January 2003. Immediately before the invasion, UN Inspectors had checked the locked bunker doors, but not the actual contents; the bunkers also had large ventilation shafts that were not sealed. By October, the material was no longer present. The IAEA expressed concerns that the material might have been looted after the invasion, posing a nuclear proliferation threat. The US released satellite photographs from March 17, showing trucks at the site large enough to remove substantial amounts of material before US forces reached the area in April. Ultimately, Major Austin Pearson of Task Force Bullet, a task force charged with securing and destroying Iraqi ammunition after the invasion, stated that the task force had removed about 250 tons of material from the site and had detonated it or used it to detonate other munitions. Similar concerns were raised about other dual use materials, such as high strength aluminum; before the invasion, the US cited them as evidence for an Iraqi nuclear weapons program, while the IAEA was satisfied that they were being used for permitted industrial uses; after the war, the IAEA emphasized the proliferation concern, while the Duelfer report mentioned the material's use as scrap. Possible chemical weapons laboratories have also been found which were built subsequent to the 2003 invasion, apparently by insurgent forces.[92]

On August 2, 2004, President Bush stated "Knowing what I know today we still would have gone on into Iraq. ... The decision I made is the right decision. The world is better off without Saddam Hussein in power."[93]

Allegations of Iraqi support to terrorist organizations

[edit]Along with Iraq's alleged development of weapons of mass destruction, another justification for invasion was the purported link between Saddam Hussein's government and terrorist organizations, in particular al-Qaeda.[94] In that sense, the Bush administration cast the Iraq war as part of the broader War on Terrorism. On February 11, 2003, FBI Director Robert Mueller testified to Congress that "seven countries designated as State Sponsors of Terrorism – Iran, Iraq, Syria, Sudan, Libya, Cuba, and North Korea – remain active in the US and continue to support terrorist groups that have targeted Americans".[43][44]

In October 2002, according to Pew Research Center, 66% of Americans believed that "Saddam Hussein helped the terrorists in the September 11th attacks"; and 21% said he was not involved in 9/11.[95] A poll published by The Washington Post in September 2003 estimated that nearly seven-tenths of Americans continued to the hold the perception that Ba'athist Iraq had a role in the September 11 attacks. The poll further revealed that approximately 80% of Americans suspected Saddam Hussein of providing material support to al-Qaeda.[96][97]

As with the argument that Iraq was developing biological and nuclear weapons, evidence linking Saddam Hussein and al-Qaeda was discredited by multiple US intelligence agencies soon after the invasion of Iraq.[5]

Al-Qaeda

[edit]In asserting a link between Saddam Hussein and al-Qaeda, the U.S. government focused special attention on alleged ties between Saddam Hussein and Jordanian terrorist Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, whom U.S. Secretary of State Powell called a "collaborator of Osama bin Laden".[94] During his February 2003 presentation in the UN Security Council, Powell claimed:

"... the Zarqawi network helped establish another poison and explosive training center camp, and this camp is located in northeastern Iraq...

Those helping to run this camp are Zarqawi lieutenants operating in northern Kurdish areas outside Saddam Hussein's controlled Iraq. But Baghdad has an agent in the most senior levels of the radical organization Ansar al-Islam that controls this corner of Iraq. In 2000, this agent offered al-Qaida safe haven in the region. ...

Going back to the early and mid-1990s when bin Laden was based in Sudan, ... Saddam and bin Laden reached an understanding that al-Qaida would no longer support activities against Baghdad. Early al-Qaida ties were forged by secret high-level intelligence service contacts with al-Qaida, secret Iraqi intelligence high-level contacts with al-Qaida. ...

Saddam was also impressed by al-Qaida's attacks on the USS Cole in Yemen in October 2000.

Iraqis continue to visit bin Laden in his new home in Afghanistan. A senior defector, one of Saddam's former intelligence chiefs in Europe, says Saddam sent his agents to Afghanistan sometime in the mid-1990s to provide training to al-Qaida members on document forgery.

From the late 1990s until 2001, the Iraqi Embassy in Pakistan played the role of liaison to the al-Qaida organization."

— Colin Powell's presentation to the UN Security Council, 5 February 2003, [42]

Soon after the start of the war, however, evidence of such ties was discredited by multiple US intelligence agencies, including the Central Intelligence Agency CIA, the Defense Intelligence Agency, and the Defense Department's Inspector General's Office. A CIA report in early October 2004 "found no clear evidence of Iraq harboring Abu Musab al-Zarqawi".[98] More broadly, the CIA's Kerr Group summarized in 2004 that despite "a 'purposely aggressive approach' in conducting exhaustive and repetitive searches for such links ... [the US] Intelligence Community remained firm in its assessment that no operational or collaborative relationship existed".[99] Despite these findings, US Vice President Dick Cheney continued to assert that a link existed between al-Qaeda and Saddam Hussein prior to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, which drew criticism from members of the intelligence community and leading Democrats.[100] As of the invasion, the State Department listed 45 countries, including the United States, where al-Qaeda was active. Iraq was not one of them.[101]

These claims were supported by the July 2005 release of the so-called Downing Street memo, in which Richard Dearlove (then head of British foreign intelligence service MI6) wrote that "the intelligence and facts were being fixed [by the US] around the policy" of removing Saddam Hussein from power.[80] In addition, in his April 2007 report Acting Inspector General Thomas F. Gimble found that the Defense Department's Office of Special Plans – run by then-Undersecretary of Defense Douglas J. Feith, a close ally of Vice President Dick Cheney and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld – purposely manipulated evidence to strengthen the case for war.[5] The Inspector General's report also highlighted the role of members of the Iraqi National Congress, a group headed by Ahmad Chalabi, in providing false intelligence about connections with al-Qaeda to build support for a US invasion.[102][103]

Other terrorist organizations

[edit]In making its case for the invasion of Iraq, the Bush administration also referenced Saddam Hussein's relationships with terrorist organizations other than al-Qaeda. Saddam Hussein provided financial assistance to the families of Palestinians killed in the conflict – including as much as $25,000 to the families of suicide bombers, some of whom were working with militant organizations in the Middle East such as Hamas.[104][105][106][107] In his presentation to the UN Security Council on 5 February 2003, Colin Powell claimed:

"... the record of Saddam Hussein's cooperation with other Islamist terrorist organizations is clear. Hamas, for example, opened an office in Baghdad in 1999 and Iraq has hosted conferences attended by Palestine Islamic Jihad. These groups are at the forefront of sponsoring suicide attacks against Israel."

Abdul Rahman Yasin, a suspect detained shortly after the 1993 World Trade Center bombing attacks, fled once released into Iraq. Shortly after, the FBI discovered evidence linking him to the bomb. After the invasion, Iraqi government official documents translated from Arabic to English described how Saddam's regime provided monthly payments to Yasin while he lived in the United States. Yasin is on the FBI's most wanted terrorists list, and is still at large.[108][109][when?]

Counter-terrorism claims

[edit]In addition to claiming that the Saddam Hussein government had ties to al-Qaeda, the US government and other supporters of the war argued for continued involvement in Iraq as a means to combat terrorism. U.S President George W. Bush regularly described the Iraq War as the "central front in the war on terror".[110] In a press conference held on 6 March 2003, Bush argued:

"Iraq is a part of the war on terror. Iraq is a country that has got terrorist ties, it's a country with wealth, it's a country that trains terrorists, a country that could arm terrorists. And our fellow Americans must understand, in this new war against terror, that we not only must chase down al Qaeda terrorists, we must deal with weapons of mass destruction as well."[111]

A few intelligence experts claimed that the Iraq War actually increased terrorism, even though no acts of terrorism occurred in the US. London's conservative International Institute for Strategic Studies concluded in 2004 that the occupation of Iraq had become "a potent global recruitment pretext" for jihadists and that the invasion "galvanized" al-Qaeda and "perversely inspired insurgent violence" there.[citation needed] Counter-terrorism expert Rohan Gunaratna called the invasion of Iraq a "fatal mistake" that greatly increased terrorism in the Middle East.[112] The US National Intelligence Council concluded in a January 2005 report that the war in Iraq had become a breeding ground[colloquialism] for a new generation of terrorists; David B. Low, the national intelligence officer for transnational threats, indicated that the report concluded that the war in Iraq provided terrorists with "a training ground, a recruitment ground, the opportunity for enhancing technical skills. ... here is even, under the best scenario, over time, the likelihood that some of the jihadists who are not killed there will, in a sense, go home, wherever home is, and will therefore disperse to various other countries."[verify quote punctuation] The Council's Chairman Robert L. Hutchings said, "At the moment, Iraq is a magnet for international terrorist activity."[113] And the 2006 National Intelligence Estimate outlined the considered judgment of all 16 US intelligence agencies, held that "The Iraq conflict has become the 'cause celebre' for jihadists, breeding a deep resentment of US involvement in the Muslim world and cultivating supporters for the global jihadist movement."[114]

A study published in 2005 by American political scientists Amy Gershkoff and Shana Kushner Gadarian, which analyzed George Bush's speeches and polling data between September 2001 and May 2003, found that it was the American public's views about Saddam Hussein's perceived connections with al-Qaeda and the September 11 attacks that became the major catalyst behind the rise in support of the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq among Americans.[115] According to the findings of the study:

"2003 war in Iraq received high levels of public support because the Bush administration successfully framed the conflict as an extension of the war on terror, which was a response to the September 11, 2001, attack on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Our analysis of Bush's speeches reveals that the administration consistently connected Iraq with 9/11. New York Times coverage of the president's speeches featured almost no debate over the framing of the Iraq conflict as part of the war on terror. This assertion had tremendous influence on public attitudes, as indicated by polling data from several sources."[116]

Al-Qaeda leaders also publicly cited the Iraq War as a boon to their recruiting and operational efforts, providing both evidence to jihadists worldwide that America is at war with Islam, and the training ground for a new generation of jihadists to practice attacks on American forces. In October 2003, Osama bin Laden announced: "Be glad of the good news: America is mired in the swamps of the Tigris and Euphrates. Bush is, through Iraq and its oil, easy prey. Here is he now, thank God, in an embarrassing situation and here is America today being ruined before the eyes of the whole world."[117] Echoing this sentiment, al-Qaeda commander Seif al-Adl gloated about the war in Iraq, indicating, "The Americans took the bait and fell into our trap."[citation needed] A letter thought to be from al-Qaeda leader Atiyah Abd al-Rahman found in Iraq among the rubble where al-Zarqawi was killed and released by the US military in October 2006, indicated that al-Qaeda perceived the war as beneficial to its goals:

"The most important thing is that the jihad continues with steadfastness ... indeed, prolonging the war is in our interest."[118]

Human rights

[edit]The US cited the United Nations condemnation of Saddam Hussein's human rights abuses as one of several reasons for the Iraq invasion.

As evidence supporting US and British claims about Iraqi weapons of mass destructions weakened, the Bush administration began to focus more upon the other issues that Congress had articulated within the Iraq Resolution, such as human rights violations of the Saddam Hussein government as justification for military intervention.[119] That the Saddam Hussein government consistently and violently violated the human rights of its people is in little doubt.[120] During his more than twenty-year rule, Saddam Hussein tortured and killed thousands of Iraqi citizens, including gassing and killing thousands of Kurds in northern Iraq during the mid-1980s, brutally repressing Shia and Kurdish uprisings following the 1991 Gulf War, and a fifteen-year campaign of repression and displacement of the Marsh Arabs in Southern Iraq. In the 2003 State of the Union Address, President Bush mentioned Saddam's government practices of obtaining confessions by torturing children while their parents are made to watch, electric shock, burning with hot irons, dripping acid on the skin, mutilation with electric drills, cutting out tongues, and rape.[121][122][123][124]

Many critics have argued, despite its repeated mention in the Joint Resolution, that human rights was never a principal justification for the war, and that it became prominent only after evidence concerning weapons of mass destructions and Saddam Hussein's links to terrorism became discredited. For example, during a July 29, 2003, hearing of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, then Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz spent the majority of his testimony discussing Saddam Hussein's human rights record, causing Senator Lincoln Chafee (R-RI) to complain that "in the months leading up to the war it was a steady drum beat of weapons of mass destruction, weapons of mass destruction, weapons of mass destruction. And, Secretary Wolfowitz, in your almost hour-long testimony here this morning, once – only once did you mention weapons of mass destruction, and that was an ad lib."[125]

Leading human rights groups such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International further argued that even had human rights concerns been a central rationale for the invasion, military intervention would not have been justifiable on humanitarian grounds. As Human Rights Watch's Ken Roth wrote in 2004, despite Saddam Hussein's horrific human rights record, "the killing in Iraq at the time was not of the exceptional nature that would justify such intervention".[126]

More broadly, war critics have argued that the US and Europe supported the Saddam Hussein regime during the 1980s, a period of some of his worst human rights abuses, thus casting doubt on the sincerity of claims that military intervention was for humanitarian purposes. The US and Europe provided considerable military and financial support during the Iran–Iraq war with full knowledge that the Saddam Hussein government was regularly using chemical weapons on Iranian soldiers and Kurdish insurgents. US aid was aimed primarily to prevent Iraqi defeat after 1983.[127] Following along this line, critics of the use of human rights as a rationale, such as Columbia University Law Professor Michael Dorf, have pointed out that during his first campaign for president Bush was highly critical of using US military might for humanitarian ends.[128][129]

Others questioned why military intervention for humanitarian reasons would supposedly have been justified in Iraq but not in other countries with even worse human rights violations, such as Darfur.[125]

United Nations

[edit]By article 1 of the UN Charter, the United Nations has the responsibility: "To achieve international co-operation in solving international problems of an economic, social, cultural, or humanitarian character, and in promoting and encouraging respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion".[130] By UN Charter article 39, the responsibility for this determination lies with the Security Council.[130][needs context]

Ending sanctions

[edit]US Vice President Dick Cheney, who called the sanctions "the most intrusive system of arms control in history",[131] cited the breakdown of the sanctions as one rationale for the Iraq war.[132] Accepting a controversial large estimate of casualties due to sanctions,[133] Walter Russell Mead argued on behalf of such a war as a better alternative than continuing the sanctions regime, since "Each year of containment is a new Gulf War."[134] However, economist Michael Spagat "argue[s] that the contention that sanctions had caused the deaths of more than half a million children is [as were weapons of mass destruction claims] very likely to be wrong".[135]

Oil

[edit]Statements indicating oil as a rationale

[edit]Bush's Treasury Secretary Paul O'Neill said that Bush's first two National Security Council meetings discussed invading Iraq. He was given briefing materials entitled "Plan for post-Saddam Iraq", which envisioned dividing up Iraq's oil wealth. A Pentagon document dated March 5, 2001, was titled "Foreign Suitors for Iraqi Oilfield contracts", and included a map of potential areas for exploration.[136]

In July 2003, Polish foreign minister, Włodzimierz Cimoszewicz, said "We have never hidden our desire for Polish oil companies to finally have access to sources of commodities." This remark came after a group of Polish firms had signed a deal with Kellogg, Brown and Root, a subsidiary of Halliburton. Cimoszewicz stated that access to Iraq's oilfields "is our ultimate objective".[137]

One report by BBC journalist Gregory Palast citing unnamed "insiders" alleged that the US "called for the sell-off of all of Iraq's oil fields"[138] and planned for a coup d'état in Iraq long before September 11.[138] Palast also wrote that the "new plan was crafted by neo-conservatives intent on using Iraq's oil to destroy the OPEC cartel through massive increases in production above OPEC quotas",[138] but Iraq oil production decreased following the Iraq War.[139]

General John Abizaid, CENTCOM commander from 2003 to 2007, said of the Iraq war: "first of all I think it's really important to understand the dynamics that are going on in the Middle East, and of course it's about oil, it's very much about oil and we can't really deny that".[140][141]

2008 Republican Presidential Candidate John McCain was forced to clarify his comments suggesting the Iraq war involved US reliance on foreign oil. "My friends, I will have an energy policy that we will be talking about, which will eliminate our dependence on oil from the Middle East that will prevent us from having ever to send our young men and women into conflict again in the Middle East", McCain said. To clarify his comments, McCain explained that "the word 'again' was misconstrued; I want us to remove our dependency on foreign oil for national security reasons, and that's all I mean."[142]

Many critics have focused upon administration officials' past relationships with energy corporations. Both George W. Bush and Dick Cheney were formerly CEOs of oil and oil-related companies such as Arbusto, Harken Energy, Spectrum 7, and Halliburton. Before the 2003 invasion of Iraq and even before the War on Terror, the administration had prompted anxiety over whether the private sector ties of cabinet members (including National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice, former director of Chevron, and Commerce Secretary Donald Evans, former head of Tom Brown Inc.) would affect their judgment on energy policy.[143]

Prior to the war, the CIA saw Iraqi oil production and illicit oil sales as Iraq's key method of financing. The CIA's October 2002 unclassified white paper on "Iraq's Weapons of Mass Destruction Programs" states on page one under the "Key Judgments, Iraq's Weapons of Mass Destruction Programs" heading that "Iraq's growing ability to sell oil illicitly increases Baghdad's capabilities to finance weapons of mass destruction programs".[144]

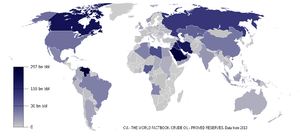

Private oil business

[edit]Iraq holds the world's fifth-largest proven oil reserves at 141 billion barrels (2.24×1010 m3),[145] with increasing exploration expected to enlarge them beyond 200 billion barrels (3.2×1010 m3).[146] For comparison, Venezuela – the largest proven source of oil in the world – has 298 billion barrels (4.74×1010 m3) of proven oil reserves.[145]

Organizations such as the Global Policy Forum (GPF) asserted that Iraq's oil is "the central feature of the political landscape" there, and that as a result of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, "'friendly' companies expect to gain most of the lucrative oil deals that will be worth hundreds of billions of dollars in profits in the coming decades". According to the GPF, US influence over the 2005 Constitution of Iraq has made sure it "contains language that guarantees a major role for foreign companies".[146][147]

Strategic importance of oil

[edit]

Oil exerts tremendous economic and political influence worldwide, although the line between political and economic influence is not always distinct. The importance of oil to national security is unlike that of any other commodity:

Modern warfare particularly depends on oil, because virtually all weapons systems rely on oil-based fuel – tanks, trucks, armored vehicles, self-propelled artillery pieces, airplanes, and naval ships. For this reason, the governments and general staff of powerful nations seek to ensure a steady supply of oil during wartime, to fuel oil-hungry military forces in far-flung operational theaters. Such governments view their companies' global interests as synonymous with the national interest and they readily support their companies' efforts to control new production sources, to overwhelm foreign rivals, and to gain the most favorable pipeline routes and other transportation and distribution channels.[148]

Critics of the Iraq War contend that US officials and representatives from the private sector were planning just this kind of mutually supportive relationship as early as 2001, when the James Baker III Institute for Public Policy and the Council on Foreign Relations produced "Strategic Energy Policy: Challenges for the 21st Century", a report describing the long-term threat of energy crises such as blackouts and rising fuel prices then playing havoc with the state of California. The report recommended a comprehensive review of US military, energy, economic, and political policy toward Iraq "with the aim to lowering anti-Americanism in the Middle East and elsewhere, and set the groundwork to eventually ease Iraqi oil-field investment restrictions".[149] The report's urgent tone stood in contrast to the relatively calm speech Chevron CEO Kenneth T. Derr had given the Commonwealth Club of California two years earlier, before the California electricity crisis, where he said, "It might surprise you to learn that even though Iraq possesses huge reserves of oil and gas – reserves I'd love Chevron to have access to – I fully agree with the sanctions we have imposed on Iraq."[150]

Oil and foreign relations

[edit]Post-Iraq invasion opinion polls conducted in Jordan, Morocco, Pakistan, and Turkey showed that the majority of each country's population tended to "doubt the sincerity of the War on Terrorism", which they characterized instead as "an effort to control Middle East oil and to dominate the world"[according to whom?].[151]

Although there has been disagreement about where the alleged will to control and dominate originates, skeptics of the War on Terror have pointed early[152] and often[153] to the Project for a New American Century, a neoconservative think tank established in 1997 by William Kristol and Robert Kagan. The organization made plain its position on oil, territory, and the use of force in series of publications, including:

- a 1998 letter to President Bill Clinton:

It hardly needs to be added that if Saddam does acquire the capability to deliver weapons of mass destruction, as he is almost certain to do if we continue along the present course, the safety of American troops in the region, of our friends and allies like Israel and the moderate Arab states, and a significant portion of the world's supply of oil will all be put at hazard. ... The only acceptable strategy is one that eliminates the possibility that Iraq will be able to use or threaten to use weapons of mass destruction. In the near-term, this means a willingness to undertake military action as diplomacy is clearly failing.[154]

- a September 2000 report on foreign policy:

American forces, along with British and French units ... represent the long-term commitment of the United States and its major allies to a region of vital importance. Indeed, the United States has for decades sought to play a more permanent role in Gulf regional security. While the unresolved conflict with Iraq provides the immediate justification, the need for a substantial American force presence in the Gulf transcends the issue of the regime of Saddam Hussein.[155]

- a May 2001 call to "Liberate Iraq":

Twice since 1980, Saddam has tried to dominate the Middle East by waging wars against neighbors that could have given him control of the region's oil wealth and the identity of the Arab world.[156]

- a 2004 justification:

His [Saddam Hussein's] clear and unwavering ambition, an ambition nurtured and acted upon across three decades, was to dominate the Middle East, both economically and militarily, by attempting to acquire the lion's share of the region's oil and by intimidating or destroying anyone who stood in his way. This, too, was a sufficient reason to remove him from power.[157]

Of 18 signatories to the 1998 PNAC letter, 11 would later occupy positions in President Bush's administration:

- Elliott Abrams,

- Richard Armitage,

- John R. Bolton,

- Paula Dobriansky,

- Francis Fukuyama,

- Zalmay Khalilzad,

- Richard Perle,

- Peter W. Rodman,

- Donald Rumsfeld,

- Paul Wolfowitz, and

- Robert B. Zoellick.[154]

Administration officials Dick Cheney, Eliot A. Cohen, and Lewis Libby signed the 1997 PNAC "Statement of Principles".[158]

Wolfowitz Cabal

[edit]Just after the US invasion of Afghanistan, The Guardian reported plans to invade Iraq and seize its oil reserves around Basra and use the proceeds to finance Iraqi oppositions in the south and the north. Later the US intelligence community called these claims as not credible and said that they had no plan to attack Iraq. On October 14, 2001, The Guardian reported:

The group, which some in the State Department and on Capitol Hill refer to as the "Wolfowitz cabal", after Deputy Secretary of Defence Paul Wolfowitz, was yesterday laying the ground for a strategy that envisions the use of air support and the occupation of southern Iraq with American ground troops to install an Iraqi opposition group based in London at the helm of a new government. Under the plan, American troops would also seize the oil fields around Basra, in south-eastern Iraq, and sell the oil to finance the Iraqi opposition in the south and the Kurds in the north, one senior official said.[159]

Petrodollar warfare

[edit]The term petrodollar warfare refers to the idea that the international use of the United States dollar as the standard means of settling oil transactions is a kind of economic imperialism enforced by violent military interventions against countries like Iraq, Iran, and Venezuela, and is a key driver of world politics. The term was coined by William R. Clark, who has written a book with the same title.[160] The phrase oil currency war is sometimes used with the same meaning. In reality, the use of dollars in international oil transactions increases overall U.S. dollar demand by only a tiny fraction, and the dollar's overall status as the major international reserve currency has relatively few tangible benefits for the United States economy as well as some drawbacks.[161][162]

Statements against oil as a rationale

[edit]The New York Times reported that in February 2003, Saddam Hussein had offered, through a clandestine backchannel, to give the United States first priority as it related to Iraq oil rights, as part of a deal to avert an impending invasion. The overtures intrigued the Bush administration but were ultimately rebuffed.[163]

In 2002, responding to a question about coveting oil fields, George W. Bush said "Those are the wrong impressions. I have a deep desire for peace. That's what I have a desire for. And freedom for the Iraqi people. See, I don't like a system where people are repressed through torture and murder in order to keep a dictator in place. That troubles me deeply. And so the Iraqi people must hear this loud and clear, that this country never has any intention to conquer anybody."[164]

Tony Blair stated that the hypothesis that the Iraq invasion had "some[thing] to do with oil" was a "conspiracy theory": "Let me first deal with the conspiracy theory that this is somehow to do with oil ... The very reason why we are taking the action that we are taking is nothing to do with oil or any of the other conspiracy theories put forward."[165][non-primary source needed]

Then Australian Prime Minister John Howard has dismissed on multiple occasions the role of oil in the Iraq Invasion: "We didn't go there because of oil and we don't remain there because of oil."[166] In early 2003 John Howard stated, "No criticism is more outrageous than the claim that United States behavior is driven by a wish to take control of Iraq's oil reserves."[167]

Economist Gary S. Becker stated in 2003 that "if oil were the driving force behind the Bush Administration's hard line on Iraq, avoiding war would be the most appropriate policy".[168][169]

According to economist Ismael Hossein-Zadeh (2006): "there is no evidence that, at least in the case of the current invasion of Iraq, oil companies pushed for or supported the war. On the contrary, there is strong evidence that, in fact, oil companies did not welcome the war because they prefer stability and predictability to periodic oil spikes that follow war and political convulsion".[170]

Political scientist John S. Duffield wrote in 2012 that "no compelling evidence, either in the form of declassified documents or participants' memoirs, has yet emerged indicating that oil was a prominent factor or constant consideration in the thinking of decision makers within the Bush administration".[171]

Political scientist Jeff Colgan wrote in 2013 that "Even years after the 2003 Iraq War, there is still no consensus on the degree to which oil played a role in that war." Colgan said that the fact that oil contracts were awarded to non-American companies, including Russian and Chinese corporations, is evidence against the view that the war was for oil.[172] Journalist Muhammad Idrees Ahmad wrote in 2014 that:

Inferring oil as the war's presiding motive from the fact that US forces showed extraordinary solicitude towards Iraq's energy infrastructure assumes that if the war was not for oil then the invaders would not care about it. Gulf energy resources have always been a vital US interest. On no other occasion has the US had to occupy a country to secure them. Regardless of why Iraq was invaded, it is reasonable to assume that an occupier would exploit rather than destroy its assets. Indeed, the neoconservatives used oil both as an incentive to get the energy industry onside and as a disincentive against dissent, threatening exclusion from future oil contracts. Oil may have played a part in the thinking of some policy makers – as Juan Cole argues it had in Dick Cheney's – but even Cole admits that Iraq was invaded only because the Israel lobby was blocking all other means of access to it. If oil were indeed the overriding concern, it is likelier that we would have US boots on Venezuelan ground. After all, nowhere were US interests more threatened than in Latin America, and few governments had a more provocative attitude towards the US than Hugo Chavez's. Yet, the US was able to do little when the Venezuelan government rewrote laws to claim 30 per cent (up from 16 per cent) of the oil profits for the national oil company.

— Muhammad Idrees Ahmad, The Road to Iraq: The Making of a Neoconservative War[169]

Other rationales

[edit]Bringing democracy to the Middle East

[edit]One of the rationales that the Bush administration employed periodically during the lead-up to the Iraq war was that deposing Saddam Hussein and installing a democratic government in Iraq would promote democracy in other Middle Eastern countries.[173] The United States also proclaimed that the monarchies in Jordan and Saudi Arabia, and the military government of Pakistan were American allies, despite the human rights abuses and subversion of democracy attributed to them respectively. As Vice President Cheney argued in an August 2002 speech to the annual Veterans of Foreign Wars convention, "When the gravest of threats are eliminated, the freedom-loving peoples of the region will have a chance to promote the values that can bring lasting peace."[174]

At a 2003 Veterans Day address, President Bush stated:[175]

Our mission in Iraq and Afghanistan is clear to our service members – and clear to our enemies. Our men and women are fighting to secure the freedom of more than 50 million people who recently lived under two of the cruelest dictatorships on earth. Our men and women are fighting to help democracy and peace and justice rise in a troubled and violent region. Our men and women are fighting terrorist enemies thousands of miles away in the heart and center of their power, so that we do not face those enemies in the heart of America.

Establishing long-term Middle East military presence

[edit]US General Jay Garner, who was in charge of planning and administering post-war reconstruction in Iraq, compared the US occupation of Iraq to the Philippine model in a 2004 interview in National Journal: "Look back on the Philippines around the turn of the 20th century: they were a coaling station for the navy, and that allowed us to keep a great presence in the Pacific. That's what Iraq is for the next few decades: our coaling station that gives us great presence in the Middle East", "One of the most important things we can do right now is start getting basing rights with (the Iraqi authorities)", "I hope they're there a long time. ... And I think we'll have basing rights in the north and basing rights in the south ... we'd want to keep at least a brigade",[verify quote punctuation] Garner added.[176]

Also, the House report accompanying the emergency spending legislation said the money was "of a magnitude normally associated with permanent bases".[177]

Other allegations

[edit]Nabil Shaath told the BBC that according to minutes of a conference with Palestinian leader Mahmoud Abbas, Bush said, "God inspired me to hit al Qaeda, and so I hit it. And I had the inspiration to hit Saddam, and so I hit him."[178] Haaretz provided a similar translation of the minutes. When an Arabist at the Washington Post translated the same transcript, Bush was said to have indicated that God inspired him to "end the tyranny in Iraq" instead.[179]

In a 2003 interview, Jacques Chirac, President of France at that time, affirmed that President George W. Bush asked him to send troops to Iraq to stop Gog and Magog, the "Bible's satanic agents of the Apocalypse". According to Chirac, the American leader appealed to their "common faith" (Christianity) and told him: "Gog and Magog are at work in the Middle East ... The biblical prophecies are being fulfilled ... This confrontation is willed by God, who wants to use this conflict to erase his people's enemies before a New Age begins."[180][citation needed]

Purported Iraqi intelligence plots

[edit]David Harrison claimed in the Telegraph to have found secret documents that purported to show Russian President Vladimir Putin offering the use of assassins to Saddam's Iraqi regime to kill Western targets on November 27, 2000.[181]

Alleged terrorist links

[edit]Abdul Rahman Yasin, a suspect detained shortly after the 1993 US World Trade Center Bombing attacks, fled upon release into Iraq. Shortly after release, the FBI had discovered evidence linking him to the development of the bomb. After the invasion, Iraqi government official documents translated from Arabic to English described that Saddam's regime provided monthly payments to Yasin while he was residing in the United States. Yasin is on the FBI's most wanted terrorists list, and is still[when?] at large.[108][109]

John Lumpkin, Associated Press Writer, consolidated statements made by Vice President Cheney concerning the 1993 WTC bombing and Iraq. Cheney indicated Saddam's Iraqi government claimed to have FBI fugitive Yasin, alleged participant in the mixing of the chemicals making the bomb used in the 1993 WTC attack, in an Iraqi prison. During negotiations in the weeks prior to the invasion of Iraq, Saddam refused to extradite him.[182]

Fox News claimed that evidence found in Iraq after the invasion was used to stop the attempted assassination of the Pakistani ambassador in New York with a shoulder-fired rocket.[183][unreliable source?]

US government officials claimed that after the invasion, Yemen and Jordan stopped Iraqi terrorist attacks against Western targets in those nations. US intelligence also warned 10 other countries that small groups of Iraqi intelligence agents might be readying similar attacks.[184]

After the Beslan school hostage crisis, public school layouts and crisis plans were retrieved on a disk recovered during an Iraqi raid; this caused concerns in the United States. The information on the disks was "all publicly available on the Internet" and US officials "said it was unclear who downloaded the information and stressed there is no evidence of any specific threats involving the schools".[185]

Pressuring Saudi Arabia

[edit]According to this hypothesis, the operations in Iraq occurred as a result of the US attempting to put pressure on Saudi Arabia. Much of the funding for al-Qaeda came from sources in Saudi Arabia through channels left over from the Afghan War. The US, wanting to staunch such financial support, pressured the Saudi leadership to cooperate with the West. The Saudis in power, fearing an Islamic backlash if they cooperated with the US which could push them from power, refused. In order to put pressure on Saudi Arabia to cooperate, the invasion of Iraq was conceived. Such an action would demonstrate the power of the US military, put US troops near to Saudi Arabia, and demonstrate that the US did not need Saudi allies to project itself in the Middle East.[186]

Display of US military power to assert US global supremacy

[edit]Ahsan Butt argues that the invasion of Iraq was partially motivated by a desire of American policymakers to reassert American prestige and status following 9/11. Butt argues that prior to 9/11 the United States was recognized internationally as the undisputed world superpower and hegemon, but the 9/11 attacks called this status into question. Butt argues that invading Iraq was a means of allowing the United States to demonstrate that it was and intended to remain a global hegemon. Since Afghanistan was too weak a nation to demonstrate American power, Iraq was also invaded. Butt argues that Saddam had also damaged American prestige as he remained defiant following the Gulf War.[187] A 2012 poll found that "Assert dominance in a New American Century" was viewed as the most important motivation for Bush, Cheney, Rumsfeld and neoconservatives by international relations experts.[188]

Criticisms

[edit]Despite these efforts to sway public opinion, the invasion of Iraq was seen by some, including Kofi Annan,[189] the United Nations Secretary-General, Lord Goldsmith, the British Attorney General,[190] and Human Rights Watch,[191] as a violation of international law,[192] breaking the UN Charter, especially since the US failed to secure UN support for an invasion of Iraq. In 41 countries the majority of the populace did not support an invasion of Iraq without UN sanction and half said an invasion should not occur under any circumstances.[193] 73 percent of the population of the United States supported an invasion.[193] To build international support the United States formed a "Coalition of the Willing" with the United Kingdom, Italy, Poland, Australia and several other countries despite a majority of citizens in these countries opposing the invasion.[193] Massive protests of the war occurred in the US and elsewhere.[194][195][196] At the time of the invasion, UNMOVIC inspectors were ordered out by the United Nations. The inspectors requested more time because "disarmament, and at any rate verification, cannot be instant".[197][198]

Following the invasion, no stockpiles of weapons of mass destruction were found, although about 500 abandoned chemical munitions, mostly degraded and left over from Iraq's Iran–Iraq war, were collected from around the country.[199][200][better source needed] The Kelly Affair highlighted a possible attempt by the British government to cover-up fabrications in British intelligence, the exposure of which would have undermined Tony Blair's original rationale for involvement in the war. The US Senate Select Committee on Intelligence found no substantial evidence of links between Iraq and al-Qaeda.[201] President George W. Bush has since admitted that "much of the intelligence turned out to be wrong".[202][203][204] The Iraq Survey Group's final report of September 2004 stated,

"While a small number of old, abandoned chemical munitions have been discovered, ISG judges that Iraq unilaterally destroyed its undeclared chemical weapons stockpile in 1991. There are no credible indications that Baghdad resumed production of chemical munitions thereafter, a policy ISG attributes to Baghdad's desire to see sanctions lifted, or rendered ineffectual, or its fear of force against it should weapons of mass destruction be discovered."[205]