Hyrax

| Hyraxes Temporal range: Eocene–recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

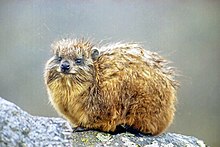

| Rock hyrax (Procavia capensis) Erongo, Namibia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Superorder: | Afrotheria |

| Clade: | Paenungulatomorpha |

| Grandorder: | Paenungulata |

| Order: | Hyracoidea Huxley, 1869 |

| Subgroups | |

For extinct genera, see text | |

| |

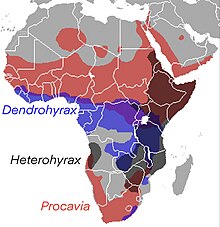

| The range map of Procaviidae, the only living family within Hyracoidea | |

Hyraxes (from Ancient Greek ὕραξ hýrax 'shrew-mouse'), also called dassies,[1][2] are small, stout, thickset, herbivorous mammals in the family Procaviidae within the order Hyracoidea. Hyraxes are well-furred, rotund animals with short tails.[3] Modern hyraxes are typically between 30 and 70 cm (12 and 28 in) in length and weigh between 2 and 5 kg (4 and 11 lb). They are superficially similar to marmots, or over-large pikas, but are much more closely related to elephants and sirenians. Hyraxes have a life span from nine to 14 years. Both types of "rock" hyrax (P. capensis and H. brucei) live on rock outcrops, including cliffs in Ethiopia[4] and isolated granite outcrops called koppies in southern Africa.[5]

With one exception, all hyraxes are limited to Africa; the exception is the rock hyrax (P. capensis) which is also found in adjacent parts of the Middle East.

Hyraxes were a much more diverse group in the past encompassing species considerably larger than modern hyraxes. The largest known extinct hyrax, Titanohyrax ultimus, has been estimated to weigh 600–1,300 kilograms (1,300–2,900 lb), comparable to a rhinoceros.[6]

Characteristics

[edit]Hyraxes retain or have redeveloped a number of primitive mammalian characteristics; in particular, they have poorly developed internal temperature regulation,[7] for which they compensate by behavioural thermoregulation, such as huddling together and basking in the sun.

Unlike most other browsing and grazing animals, they do not use the incisors at the front of the jaw for slicing off leaves and grass; rather, they use the molar teeth at the side of the jaw. The two upper incisors are large and tusk-like, and grow continuously through life, similar to those of rodents. The four lower incisors are deeply grooved "comb teeth". A diastema occurs between the incisors and the cheek teeth. The permanent dental formula for hyraxes is 1.0.4.32.0.3-4.3[8] although sometimes stated as 1.1.4.32.1.4.3[9] because the deciduous canine teeth are occasionally retained into early adulthood.[8]

Although not ruminants, hyraxes have complex, multichambered stomachs that allow symbiotic bacteria to break down tough plant materials, but their overall ability to digest fibre is lower than that of the ungulates.[10] Their mandibular motions are similar to chewing cud,[11][a] but the hyrax is physically incapable of regurgitation[12][13] as in the even-toed ungulates and some of the macropods. This behaviour is referred to in a passage in the Bible which describes hyraxes as "chewing the cud".[14][non-primary source needed] This chewing behaviour may be a form of agonistic behaviour when the animal feels threatened.[15]

The hyrax does not construct dens, but over the course of its lifetime rather seeks shelter in existing holes of great variety in size and configuration.[16] Hyraxes urinate in a designated, communal area. The viscous urine quickly dries and, over generations, accretes to form massive middens.[17][18] These structures can date back thousands of years. The petrified urine itself is known as hyraceum and serves as a record of the environment, as well as being used medicinally and in perfumes.

Hyraxes inhabit rocky terrain across sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East. Their feet have rubbery pads with numerous sweat glands, which may help the animal maintain its grip when quickly moving up steep, rocky surfaces. Hyraxes have stumpy toes with hoof-like nails; four toes are on each front foot and three are on each back foot.[19] They also have efficient kidneys, retaining water so that they can better survive in arid environments.

Female hyraxes give birth to up to four young after a gestation period of seven to eight months, depending on the species. The young are weaned at 1–5 months of age, and reach sexual maturity at 16–17 months.

Hyraxes live in small family groups, with a single male that aggressively defends the territory from rivals. Where living space is abundant, the male may have sole access to multiple groups of females, each with its own range. The remaining males live solitary lives, often on the periphery of areas controlled by larger males, and mate only with younger females.[20]

Hyraxes have highly charged myoglobin, which has been inferred to reflect an aquatic ancestry.[21]

Similarities with Proboscidea and Sirenia

[edit]Hyraxes share several unusual characteristics with mammalian orders Proboscidea (elephants and their extinct relatives) and Sirenia (manatees and dugongs), which have resulted in their all being placed in the taxon Paenungulata. Male hyraxes lack a scrotum and their testicles remain tucked up in their abdominal cavity next to the kidneys,[22][23] as do those of elephants, manatees, and dugongs.[24] Female hyraxes have a pair of teats near their armpits (axilla), as well as four teats in their groin (inguinal area); elephants have a pair of teats near their axillae, and dugongs and manatees have a pair of teats, one located close to each of the front flippers.[25][26] The tusks of hyraxes develop from the incisor teeth as do the tusks of elephants; most mammalian tusks develop from the canines. Hyraxes, like elephants, have flattened nails on the tips of their digits, rather than the curved, elongated claws usually seen on mammals.[27]

Evolution

[edit]

All modern hyraxes are members of the family Procaviidae (the only living family within Hyracoidea) and are found only in Africa and the Middle East. In the past, however, hyraxes were more diverse and widespread. At one site in Egypt, the order first appears in the fossil record in the form of Dimaitherium, 37 million years ago, but much older fossils exist elsewhere.[28] For many millions of years, hyraxes, proboscideans, and other afrotherian mammals were the primary terrestrial herbivores in Africa, just as odd-toed ungulates were in North America.

Through the middle to late Eocene, many different species existed.[29] The smallest of these were the size of a mouse but others were much larger than any extant relatives. Titanohyrax could reach 600 kg (1,300 lb) or even as much as over 1,300 kg (2,900 lb).[30] Megalohyrax from the upper Eocene-lower Oligocene was as huge as a tapir.[31][32] During the Miocene, however, competition from the newly developed bovids, which were very efficient grazers and browsers, displaced the hyraxes into marginal niches. Nevertheless, the order remained widespread and diverse as late as the end of the Pliocene (about two million years ago) with representatives throughout most of Africa, Europe, and Asia.

The descendants of the giant "hyracoids" (common ancestors to the hyraxes, elephants, and sirenians) evolved in different ways. Some became smaller, and evolved to become the modern hyrax family. Others appear to have taken to the water (perhaps like the modern capybara), ultimately giving rise to the elephant family and perhaps also the sirenians. DNA evidence supports this hypothesis, and the small modern hyraxes share numerous features with elephants, such as toenails, excellent hearing, sensitive pads on their feet, small tusks, good memory, higher brain functions compared with other similar mammals, and the shape of some of their bones.[33]

Hyraxes are sometimes described as being the closest living relative of the elephant,[34] although whether this is so is disputed. Recent morphological- and molecular-based classifications reveal the sirenians to be the closest living relatives of elephants. While hyraxes are closely related, they form a taxonomic outgroup to the assemblage of elephants, sirenians, and the extinct orders Embrithopoda and Desmostylia.[35]

The extinct meridiungulate family Archaeohyracidae, consisting of seven genera of notoungulate mammals known from the Paleocene through the Oligocene of South America,[36] is a group unrelated to the true hyraxes.

List of genera

[edit]| Phylogeny of early hyracoids | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A phylogeny of hyracoids known from the early Eocene through the middle Oligocene epoch.[39]

|

- †Dimaitherium

- †Helioseus?

- †Microhyrax

- †Seggeurius

- †Geniohyidae

- †"Saghatheriidae" (Polyphyletic)

- †Titanohyracidae

- †Pliohyracidae

- Procaviidae

- Dendrohyrax (Tree hyrax)

- †Gigantohyrax

- Heterohyrax (Bush hyrax)

- Procavia (Rock hyrax)

Extant species

[edit]In the 2000s, taxonomists reduced the number of recognized species of hyraxes. In 1995, they recognized 11 species or more. However, as of 2013, only four were recognized, with the others all considered as subspecies of one of the recognized four. Over 50 subspecies and species are described, many of which are considered highly endangered.[42] The most recently identified species is Dendrohyrax interfluvialis, which is a tree hyrax living between the Volta and Niger rivers but makes a unique barking call that is distinct from the shrieking vocalizations of hyraxes inhabiting other regions of the African forest zone.[43]

The following cladogram shows the relationship between the extant genera:[44]

| Hyracoidea |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (order) |

Human interactions

[edit]Local and indigenous names

[edit]Biblical references

[edit]

References are made to hyraxes in the Hebrew Bible (Leviticus 11:5; Deuteronomy 14:7; Psalm 104:18; Proverbs 30:26). In Leviticus they are described as lacking a split hoof and therefore not being kosher. It also describes the hyrax as chewing its cud, reflecting its observable ruminant-like mandible motions; the Hebrew phrase in question (מַעֲלֵה גֵרָה) means "bringing up cud". Some of the modern translations refer to them as rock hyraxes.[49][50]

... hyraxes are creatures of little power, yet they make their home in the crags; ...

The words "rabbit", "hare", "coney", or "daman" appear as terms for the hyrax in some English translations of the Bible.[51][52] Early English translators had no knowledge of the hyrax, so they did not give a name for them, though "badger" or "rock-badger" has also been used more recently in new translations, especially in "common language" translations such as the Common English Bible (2011).[53]

"Spain"

[edit]One of the proposed etymologies for "Spain" is that it may be a derivation of the Phoenician I-Shpania, meaning "island of hyraxes", "land of hyraxes", but the Phoenecian-speaking Carthaginians are believed to have used this name to refer to rabbits, animals with which they were unfamiliar.[54] Roman coins struck in the region from the reign of Hadrian show a female figure with a rabbit at her feet,[55] and Strabo called it the "land of the 'rabbits'".[56]

The Phoenician shpania is cognate to the modern Hebrew shafan.[57][b]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ All artiodactyl families and about 80% of the spp. were investigated. Chewing regurgitated fodder is an idle pastime, as well as an instinct associated with appetite. Characteristic movements were analyzed for undisturbed samples of animals maintained on preserves. Group-specific differences are reported in form, rhythm, frequency, and side of chewing motion. The ungulate type is characterized as a specialization. The operation is described for the first time for the order Hyracoidea. On the basis of 12 spp. of the marsupial subfamily Macropodinae rumination is inferred for the whole category. Advantages of the process are debated.[11][verification needed]

- ^ Hispania, the name that the Romans gave to the peninsular, derives from the Phoenician i-spn-ya, where the prefix i would translate as "coast", "island", or "land", ya as "region" and spn[,] in Hebrew saphan, as "rabbits" (in reality, hyraxes). The Romans, therefore, gave Hispania the meaning of "land abundant in rabbits", a use adopted by Cicero, Caesar, Pliny the Elder and, in particular, Catulo, who referred to Hispania as the cuniculus peninsula.[57]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Hyracoidea". Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Vol. 15 Mammals (online ed.). Gale Publishing.

- ^ "Dassie, n.". Dictionary of South African English (web ed.). Dictionary Unit for South African English. 2018. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ Wilson, Don E.; Mittermeier, Russell A. (eds.). Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 2. Barcelona, ES: Lynx Edicions. p. 29. ISBN 978-84-96553-77-4.

- ^ a b Aerts, Raf (2019). "Forest and woodland vegetation in the highlands of Dogu'a Tembien". In Nyssen, J.; Jacob, M.; Frankl, A. (eds.). Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains: The Dogu'a Tembien district. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Mares, Michael A. (2017). Encyclopedia of Deserts. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 288. ISBN 978-0-8061-7229-3 – via Google books.

- ^ Tabuce, Rodolphe (18 April 2016). "A mandible of the hyracoid mammal Titanohyrax andrewsi in the collections of the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris (France) with a reassessment of the species". Palaeovertebrata. 40 (1): e4. doi:10.18563/pv.40.1.e4.

- ^ Brown, Kelly Joanne (2003). Seasonal variation in the thermal biology of the rock hyrax (Procavia capensis) (PDF) (Report). School of Botany and Zoology. University of KwaZulu-Natal – via researchspace.ukzn.ac.za.

- ^ a b Ungar, Peter S. (2010). Mammal Teeth. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 148. ISBN 0-8018-9668-1.

- ^ Napier, Julie E. (2015). "Hyrocoidea (Hyraxes)". Fowler's Zoo and Wild Animal Medicine. 8: 532. doi:10.1016/B978-1-4557-7397-8.00054-2.

- ^ von Engelhardt, W.; Wolter, S.; Lawrenz, H.; Hemsley, J.A. (1978). "Production of methane in two non-ruminant herbivores". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A. 60 (3): 309–311. doi:10.1016/0300-9629(78)90254-2.

- ^ a b Hendrichs, Hubert (1966). "Vergleichende Untersuchung des Wiederkauverhaltens" [Comparative investigation of cud retainers]. Biologisches Zentralblatt (dissertation) (in German). 84 (6): 671–751. OCLC 251821046.

- ^ Björnhag, G.; Becker, G.; Buchholz, C.; von Engelhardt, W. (1994). "The gastrointestinal tract of the rock hyrax (Procavia habessinica). 1. Morphology and motility patterns of the tract". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A. 109 (3): 649–653. doi:10.1016/0300-9629(94)90205-4. PMID 8529006.

- ^ Sale, J.B. (1966). "Daily food consumption and mode of ingestion in the Hyrax". Journal of the East African Natural History Society. XXV (3): 219.

- ^ "Leviticus 11:5". Bible Gateway. Zondervan. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ^ Slifkin, Natan (11 March 2004). "Chapter Six: Shafan the hyrax" (PDF). The Camel, the Hare, and the Hyrax. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ Sale, J.B. (January 1970). "Unusual external adaptations in the rock hyrax". Zoologica Africana. 5 (1): 101–113. doi:10.1080/00445096.1970.11447384. ISSN 0044-5096.

- ^ Cutts, Elise (1 April 2023). "Stone Age Animal Urine Could Solve a Mystery about Technological Development". Scientific American. Retrieved 25 October 2024.

- ^ Yirka, Bob (19 February 2013). "Researchers analyzing hyrax urine layers to study climate change". Phys.org. Retrieved 25 October 2024.

- ^ "Hyrax". awf.org. African Wildlife Foundation.

- ^ Hoeck, Hendrik (1984). MacDonald, D. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York, NY: Facts on File. pp. 462–465. ISBN 978-0-87196-871-5.

- ^ "One protein shows elephants and moles had aquatic ancestors". nationalgeographic.com. 13 June 2013. Archived from the original on 17 June 2013.

- ^ Carnaby, Trevor (January 2008). Beat about the Bush: Mammals. Jacana Media. p. 293. ISBN 978-1-77009-240-2 – via Google books.

- ^ Sisson, Septimus (1914). The anatomy of the domestic animals. W.B. Saunders Company. p. 577 – via Google books.

- ^ Mammal Anatomy: An illustrated guide. Marshall Cavendish. 1 September 2010. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-7614-7882-9 – via Google books.

- ^ "Dugong". gbrmpa.gov.au. Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. Government of Australia.

- ^ Schrichte, David (7 June 2023). "Reproduction". SavetheManatee.org.

- ^ "Picture of hyrax feet". Dupont, Bernard

- ^ Barrow, Eugenie; Seiffert, Erik R.; Simons, Elwyn L. (2010). "A primitive hyracoid (Mammalia, Paenungulata) from the early Priabonian (Late Eocene) of Egypt". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 8 (2): 213–244. Bibcode:2010JSPal...8..213B. doi:10.1080/14772010903450407. S2CID 84398730.

- ^ Prothero, Donald R. (2006). After the Dinosaurs: The Age of Mammals. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-253-34733-6.

- ^ Tabuce, Rodolphe (2016). "A mandible of the hyracoid mammal Titanohyrax andrewsi in the collections of the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris (France) with a reassessment of the species". Palaeovertebrata. 40 (1): e4. doi:10.18563/pv.40.1.e4.

- ^ Prothero, Donald R.; Schoch, Robert M. (1989). The Evolution of Perissodactyls. Oxford University Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-19-506039-3. Retrieved 20 September 2022 – via Google books.

- ^ Rose, Kenneth D. (26 September 2006). The Beginning of the Age of Mammals. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-8018-8472-6. Retrieved 20 September 2022 – via Google books.

- ^ "Hyrax: The little brother of the elephant". Wildlife on One. BBC TV.

- ^ "Hyrax song is a menu for mating". The Economist. 15 January 2009. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- ^ Asher, R.J.; Novacek, M.J.; Geisher, J.H. (2003). "Relationships of endemic African mammals and their fossil relatives based on morphological and molecular evidence". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 10: 131–194. doi:10.1023/A:1025504124129. S2CID 39296485.

- ^ McKenna, Malcolm C.; Bell, Susan K. (1997). Classification of Mammals above the Species Level. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11013-8.

- ^ Cooper, L.N.; Seiffert, E.R.; Clementz, M.; Madar, S.I.; Bajpai, S.; Hussain, S.T.; Thewissen, J.G.M. (8 October 2014). "Anthracobunids from the middle Eocene of India and Pakistan are stem Perissodactyls". PLOS ONE. 9 (10): e109232. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j9232C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0109232. PMC 4189980. PMID 25295875.

- ^ [http://paleobiodb.org/cgi-bin/bridge.pl?a=checkTaxonInfo&taxon_no=42284 Phenacodontidae ] in the Paleobiology Database

- ^ Gheerbrant, E.; Donming, D.; Tassy, P. (2005). "Paenungulata (Sirenia, Proboscidea, Hyracoidea, and relatives)". In Rose, Kenneth D.; Archibald, J. David (eds.). The Rise of Placental Mammals: Origins and relationships of the major extant clades. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 84–105. ISBN 978-0-8018-8022-3 – via Google books.

- ^ Tabuce, R.; Seiffert, E.R.; Gheerbrant, E.; Alloing-Séguier, L.; von Koenigswald, W. (2017). "Tooth enamel microstructure of living and extinct hyracoids reveals unique enamel types among mammals". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 24 (1): 91–110. doi:10.1007/s10914-015-9317-6. S2CID 36591482.

- ^ Pickford, M.; Senut, B. (2018). "Afrohyrax namibensis (Hyracoidea, Mammalia) from the early Miocene of Elisabethfeld and Fiskus, Sperrgebiet, Namibia" (PDF). Communications of the Geological Survey of Namibia. 18: 93–112.

- ^ Shoshani, J. (2005). Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 87–89. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ "Barks in the night lead to the discovery of new species". phys.org. June 2021.

- ^ Pickford, M. (December 2005). "Fossil hyraxes (Hyracoidea: Mammalia) from the Late Miocene and Plio-Pleistocene of Africa, and the phylogeny of the Procaviidae". Palaeontologica Africana. 41: 141–161. Retrieved 14 October 2023.

- ^ "Eastern Tree Hyrax". IUCN Red List (iucnredlist.org). International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. 3 February 2014. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ Oates, John F.; Woodman, Neal; Gaubert, Philippe; Sargis, Eric J.; Wiafe, Edward D.; Lecompte, Emilie; et al. (2022). "A new species of tree hyrax (Procaviidae: Dendrohyrax) from West Africa and the significance of the Niger–Volta interfluvium in mammalian biogeography". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 194 (2): 527–552. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlab029.

- ^ "Tarjamat w maenaa hyrax fi qamus almaeani. Qamus earabiun ainjiliziun" ترجمة و معنى hyrax في قاموس المعاني. قاموس عربي انجليزي [Translation and meaning of hyrax in Almaany Dictionary. Arabic to English Dictionary]. Almaany Dictionary. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ ""Shaphan"". Strong's Concordance.

- ^ Hart, Henry Chichester (2012). Animals Mentioned in the Bible ... Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1-278-43311-0. OCLC 936245561.

- ^

Wood, John George (1877). Wood's Bible Animals. London, UK: J.W. Lyon. OCLC 976950183.

A description of the habits, structure, and uses of every living creature mentioned in the Scriptures, from the ape to the coral; and explaining all those passages in the Hebrew Bibles and the Christian Old Testament in which reference is made to beast, bird, reptile, fish, or insect. Illustrated with over one hundred new designs

- see also Wood (2014) [1888]

- ^

Wood, John George (2014) [1888]. Story of the Bible Animals (scanned ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Charles Foster's Publications. p. 367–371. OCLC 979571526. Retrieved 12 June 2024 – via Project Gutenberg.

A description of the habits and uses of every living creature mentioned in the scriptures, with explanation of passages in the Old and New Testament in which reference is made to them

- see also Wood (1877)

- ^

Buel, James W. (1889). The Living World. St. Louis, MO: Holloway & Co. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.163548.

A complete natural history of the world's creatures, fishes, reptiles, insects, birds and mammals

- ^ Elwell, Walter A.; Comfort, Philip Wesley (2008). Tyndale Bible dictionary. Tyndale House Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4143-1945-2. OCLC 232301052.

- ^ Scrase, Richard (9 November 2014). "Rabbits, fish and mice, but no rock hyrax". (staff blog). Understanding Animal Research (understandinganimalresearch.org.uk).

- ^ Burke, Ulick Ralph (1895). A History of Spain: From the earliest times to the death of Ferdinand the Catholic. Vol. 1. London, UK: Longmans, Green & Co. p. 12. hdl:2027/hvd.fl29jg.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ a b Simón, M.A., ed. (2012). Ten years conserving the Iberian lynx. Consejería de Agricultura, Pesca y Medio Ambiente. Junta de Andalucía, Seville: Government of Spain. p. 1950. ISBN 978-84-92807-80-2 – via Google books.

External links

[edit] Data related to Procaviidae at Wikispecies

Data related to Procaviidae at Wikispecies Media related to Hyracoidea at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hyracoidea at Wikimedia Commons