Pladaroxylon

| Pladaroxylon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pladaroxylon leucadendron[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae |

| Subfamily: | Asteroideae |

| Tribe: | Senecioneae |

| Genus: | Pladaroxylon Hook.f. |

| Species: | P. leucadendron

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pladaroxylon leucadendron | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

|

List

| |

Pladaroxylon is a genus of trees in the tribe Senecioneae within the family Asteraceae.

The only known species is Pladaroxylon leucadendron, native to the island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic. Commonly known as the he cabbage-tree.

Description

[edit]Pladaroxylon leucadendron is a small tree, growing to a maximum of 5 meters in height, with relatively large and cabbage like leaves.[4][5] On young trees the leaves are very large, often reaching 30 centimeters in length, but on older trees they are usually smaller. They are oval in outline, with a downy underside, and very prominent veins.[6]

The trees branch at regular intervals into two equal sized limbs and all the leaves are at the furthest ends of the branches.[4] The first branching is at 1.2–2 meters above the ground. The tree has a broad, rounded canopy when full grown.[6]

As typical of the family it has flower heads (capitula) with many flowers crowded together in one structure that resembles a single flower, each about 6 millimeters in width.[6][4] Each of these flower heads grows together with many others in a cluster called a corymb.[4] The flower heads have white petals (ray flowers) which make the clusters resemble a head of cauliflower and bloom during July.[1]

Taxonomy

[edit]The species was given its first scientific description in 1803 by Carl Ludwig Willdenow, however he named it as Solidago leucadendron, the same name previously given by Georg Forster to the species now known as Senecio leucadendron making it a botanical illegitimate name.[7] It was then described in 1838 by Augustin Pyramus de Candolle with the name Lachanodes leucadendron. The same year, but slightly later, Stephan Endlicher described it and named it Lachanodes pladaroxylon.[3] The genus Pladaroxylon was named by Joseph Dalton Hooker in 1870,[8] when he moved the species to its own genus.[3][9] It is placed in the tribe Senecioneae in the Asteraceae family. Though this is the same tribe as for the she cabbage-tree their ancestors arrived separately on the island rather than evolving from a common ancestor in their common habitat.[6]

Names

[edit]In English the species is commonly known as the "he cabbage-tree",[10] though in 1775 the trees were called the "greater-cabbage-tree" by the inhabitants of the island.[11]

Range and habitat

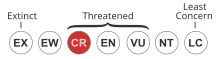

[edit]The species is endemic to the Island of Saint Helena. On the island it was only found on the central ridge from 720 to 800 meters.[12] As of 2015[update] only 55 mature individuals were known to survive in the wild.[2]

Ecology

[edit]The he cabbage-tree is a short lived tree that grows quickly to take advantage of openings in the forest canopy. Due to competition from introduced plants such as bilberry, red cinchona, and New Zealand flax (Phormium tenax) it depends on human intervention to make spaces for it to survive.[13][6] Formerly it formed a part of the native forest and grew at lower elevations than the other species called cabbage trees on the island.[6] Conservation efforts for the he cabbage-tree include the planting of more than 100 seedlings to Diana's Peak National Park, but in 2012 none of the young plants were large enough to reproduce. The very low viability of the tree's seeds hamper efforts at repopulating the species.[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Melliss, John Charles (1875). St. Helena : A Physical, Historical, and Topographical Description of the Island, Including Its Geology, Fauna, Flora and Meteorology. London: L. Reeve & Co. pp. 289–290, 300. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ^ a b Lambdon, P.W.; Ellick, S. (2016). "Pladaroxylon leucadendron". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T37596A67371569. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T37596A67371569.en. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ a b c "Pladaroxylon leucadendron (DC.) Hook.f." Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d Bremer, Kåre; Anderberg, Arne A.; Karis, Per Ola; Nordenstam, Bertil; Lundberg, Johannes; Ryding, Olof (1994). Asteraceae : Cladistics & Classification. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. pp. 507–508. ISBN 978-0-88192-275-2. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ Carlquist, Sherwin John (1974). Island Biology. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 417. ISBN 978-0-231-03562-0. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Ashmole, Philip; Ashmole, Myrtle (2000). St Helena and Ascension Island : A Natural History. Oswestry, Shropshire, England: Anthony Nelson. pp. 419–420. ISBN 978-0-904614-61-9. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ "Solidago leucadendron G.Forst". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ^ "Pladaroxylon Hook.f." Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ^ Hooker, Joseph Dalton (1871). Icones Plantarum or Figures, With Brief Descriptive Characters and Remarks, of New or Rare Plants, Selected From the Kew Herbarium (in Latin and English). Vol. XI. London: Williams and Norgate. pp. 42–43. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ Cronk, Quentin C. B. (1995). The Endemic Flora of St Helena. Oswestry, Shropshire: Anthony Nelson Ltd.

- ^ Forster, Johann Reinhold (1982). Hoare, Michael E. (ed.). The Resolution Journal of Johann Reinhold Forster, 1772-1775. Vol. IV. London: Hakluyt Society. p. 738. ISBN 978-0-904180-10-7. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ Oldfield, Sara; Lusty, Charlotte; MacKinven, Amy (1998). The World List of Threatened Trees. Cambridge, United Kingdom: World Conservation Press. p. 432. ISBN 978-1-899628-10-0. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ a b Leslie, Scott (2012). 100 under 100 : The Race to Save the World's Rarest Living Things (1st ed.). Toronto, Ontario: Collins. pp. 185–186. ISBN 978-1-4434-0428-0. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

External links

[edit] Media related to Pladaroxylon at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pladaroxylon at Wikimedia Commons