Nodaway River

| Nodaway River | |

|---|---|

A section of the Lewis and Clark map of 1814 showing the rivers of northwest Missouri. The Nodaway is spelled "Nodawa". | |

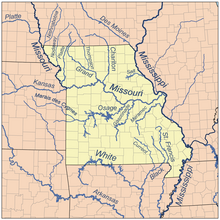

Map of Missouri rivers. | |

| Native name | Nyi At'ąwe (Iowa-Oto) |

| Location | |

| Country | US |

| State | Iowa, Missouri |

| District | Page County, Iowa, Holt County, Missouri, Nodaway County, Missouri, Andrew County, Missouri |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Clarinda, Iowa, US |

| • coordinates | 40°38′06″N 95°01′08″W / 40.635°N 95.019°W |

| • elevation | 945 ft (288 m) |

| Mouth | Missouri River |

• location | Amazonia, Missouri, US |

• coordinates | 39°54′07″N 94°57′58″W / 39.902°N 94.966°W |

• elevation | 827 ft (252 m) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Graham, MO |

| • average | 1,008 cu/ft. per sec.[1] |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | West Nodaway River |

| • right | East Nodaway River |

| "USGS Geographic Names Information System". Retrieved 17 September 2009. | |

The Nodaway River is a 65.7-mile-long (105.7 km)[2] tributary that flows from southwest Iowa through northwest Missouri into the Missouri River.

Etymology

[edit]The river's name (as "Nodawa") first appears in the journal of Lewis and Clark, who camped at the mouth of the river on July 8, 1804,[3] but who provide no derivation of the name. The name is an Otoe-Missouria term meaning "jump over water".[4] The term would be spelled today in full as Nyi At'ąwe (nyi (water) + a- (on) + t'ąwe (jump)) and would be contracted in regular speech as Nyat'ąwe or Nat'ąwe.[5]

History

[edit]Lewis and Clark camped at the river's mouth on Nodaway Island on July 8, 1804, by Nodaway, Missouri, on the border of Holt County, Missouri and Andrew County, Missouri and took note of the river.

Lewis and Clark liked the spot enough that they recommended it for the winter headquarters of Astor Expedition of 1810–12 that discovered the South Pass in Wyoming through which hundreds of settlers on the Oregon Trail, California Trail, Mormon Trail were to pass.

The river is navigable only by shallow fishing and row boats although steam ships navigated just inside its mouth. The river was the primary route for white settlers including Amos Graham and Isaac Hogan following the Platte Purchase of 1836 which opened northwest Missouri for settlement. Nodaway County, which derives its name from the river, was by far the biggest county in the purchase and the fifth largest in the state of Missouri.

Description

[edit]The Nodaway begins near Shambaugh, Iowa at the confluence of the East and West Nodaway rivers. The West Nodaway River rises northeast of Massena in eastern Cass County, Iowa, and flows 73.8 miles (118.8 km)[2] south-southwest past Villisca and Clarinda, the largest town on the river, to its junction with the East Nodaway. The East Nodaway River rises just west of Orient in Adair County and flows 72.8 miles (117.2 km)[2] southwest past Prescott, Corning, Brooks, and Nodaway to its confluence with the West Nodaway. The Middle Nodaway River rises in Adair County south of Casey and flows 60.5 miles (97.4 km)[2] southwest past Greenfield, Fontanelle, and Carbon to join the West Nodaway just below Villisca, Iowa, 20.2 miles (32.5 km)[2] above the West Nodaway's juncture with the East Nodaway. The East and West Nodaway join to form the Nodaway River four miles (6 km) north of the Iowa-Missouri border, and the river travels south, passing Bradyville on its east, before entering Missouri.

Continuing from the Iowa border in Nodaway County, Missouri, the river travels south a mile west of Burlington Junction where it intersects US 136. Continuing southerly, the river passes west of Quitman and east of Bilby Ranch Lake Conservation Area before crossing Missouri Route 46. Afterward, the river passes by Skidmore and passes under Missouri Route 113 where it quickly becomes the border between Nodaway County and Holt County. Continuing southerly, it passes between Maitland to its east and Graham to its west, and reaches the tripoint with Andrew County. The river remains the boundary between Holt and Andrew counties to the Missouri River. The Nodaway River then passes through Nodaway Valley Conservation Area, where it is channelized and flows steadily until Interstate 29. Afterward, it passes west of Honey Creek Conservation Area and east of Monkey Mountain Conservation Area, and briefly crosses into the Missouri River Valley by Nodaway, Missouri and joins the Missouri River.

Elevations in the Nodaway system range from just under 1,400 feet (430 m) above sea level at the source of the Middle Nodaway, to 950 feet (290 m) at the beginning of the main stem, to 800 feet (240 m) at its mouth on the Missouri River in Nodaway, Missouri in Andrew County, Missouri.

The Nodaway River is a sixth order river with a basin area of 1,820 square miles (4,700 km2).

The Platte River basin is to the east and the Grand River and Des Moines River basins to the northeast, with the latter defining the boundary between the Missouri River and Mississippi River basins. The west side is bound by the Tarkio River basin and in the northwest by the Nishnabotna River basin.

The Nodaway River basin is prone to extensive flooding and can contribute as much as 20% of the flood crest of the Missouri River near its mouth.

At Graham, Missouri its normal flow is 1,011 cubic feet per second (28.6 m³/s). But during the Great Flood of 1993 the river was flowing 78,300 ft³/s (2220 m³/s) at Graham.

Tributaries

[edit]Page County

[edit]Nodaway County

[edit]- Wolf Creek

- Clear Creek

- Muddy Creek

- Cuyhoga Creek

- Mill Creek

- Hagey Branch

- Headrick Creek

- Huff Creek

- Bowman Branch

- Sand Creek

- Burr Oak Creek

- Florida Creek

- Hickory Creek

- Bagby Creek

- Elkhorn Creek

- Jenkins Creek

- Hayzlett Branch

Holt County

[edit]Andrew County

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "USGS Surface Water data for Missouri: USGS Surface-Water Annual Statistics".

- ^ a b c d e U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data. The National Map Archived 2012-03-29 at the Wayback Machine, accessed March 30, 2011

- ^ "Nodaway River Watershed: Historic and Recent Use". Missouri Department of Conservation Online. Archived from the original on August 29, 2008. Retrieved 2009-04-25.

- ^ Thwaites, Reuben (1905). Early Western Travels - 1748-1846, Vol. 17. Chicago, IL: The Lakeside Press. p. 300.

- ^ "Otoe-Missouria Language". Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

References

[edit]- Bright, William (2004). Native American Placenames of the United States. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Thwaites, Reuben Gold (1905), Early Western Travels - 1748-1846. Vol. 17. The Lakeside Press.

- Trigger, Bruce, ed. (1978) Northeast. Vol. 15 of Handbook of North American Indians, ed. William C. Sturtevant. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.