Belcher Islands

Native name: ᓴᓪᓚᔪᒐᐃᑦ Sanikiluaq | |

|---|---|

Belcher Islands, Nunavut (red). | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Hudson Bay |

| Coordinates | 56°11′N 79°15′W / 56.183°N 79.250°W[1] |

| Archipelago | Belcher Islands Archipelago |

| Total islands | 1,500 |

| Major islands | Flaherty Island, Kugong Island, Tukarak Island, Innetalling Island |

| Area | 2,896 km2 (1,118 sq mi) |

| Administration | |

Canada | |

| Territory | Nunavut |

| Region | Qikiqtaaluk |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 882 (2016) |

| Pop. density | 0.30/km2 (0.78/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | Inuit |

The Belcher Islands (Inuktitut: ᓴᓪᓚᔪᒐᐃᑦ, romanized: Sanikiluaq)[2] are an archipelago in the southeast part of Hudson Bay near the centre of the Nastapoka arc. The Belcher Islands are spread out over almost 3,000 km2 (1,200 sq mi). Administratively, they belong to the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut, Canada. The hamlet of Sanikiluaq (where the majority of the inhabitants of the Belcher Islands live) is on the north coast of Flaherty Island and is the southernmost in Nunavut. Along with Flaherty Island, the other large islands are Kugong Island, Tukarak Island, and Innetalling Island.[3] Other main islands in the 1,500-island archipelago are Moore Island, Wiegand Island, Split Island, Snape Island, and Mavor Island, while island groups include the Sleeper Islands, King George Islands, and Bakers Dozen Islands.[4]

History

[edit]The archaeological evidence present on the islands indicates that they were inhabited by the Dorset culture between 500 BCE and 1000 CE. Centuries later, from 1200 to 1500, the Thule people made their presence on the islands.[5]

The first European to encounter the islands was English sea explorer Henry Hudson, the namesake of Hudson Bay, who sighted the islands in 1610.[6] In 1670, the islands and the entirety of Hudson Bay drainage basin were designated by the English king, Charles II, as Rupert's Land, managed by the Hudson's Bay Company. The islands are named after Royal Navy Admiral Sir Edward Belcher (1799–1877).

In the early 19th century, caribou herds which lived on the islands disappeared. In an alternative effort to find warm clothing, the inhabitants of the islands sought the down of eider ducks, seaducks who nest on the island.[5] In 1870, Rupert's Land was ceded to the Northwest Territories.

Before 1914, English-speaking cartographers knew very little about the Belcher Islands, which they showed on maps as specks, much smaller than their true extent. In that year a map showing them, drawn by George Weetaltuk,[7] came into the hands of Robert Flaherty, and cartographers began to represent them more accurately.[8]

In 1941, a religious movement led by Charley Ouyerack, Peter Sala, and his sister Mina caused the death by blows or exposure of nine persons, an occurrence that came to be known as the Belcher Island Murders.[9][10]

In 1999, when Nunavut was separated from Northwest Territories, the Belcher Islands were included within Nunavut, along with most islands in Hudson Bay.

Geology

[edit]

General geology

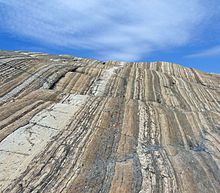

[edit]The geologic units of the Belcher Group, which forms the Belcher Islands, were deposited during the Paleoproterozoic. Combined with other Paleoproterozoic units that occur along the edge of the Superior Craton, the Belcher Group forms part of the Circum-Superior Belt.[11]

From youngest to oldest, the Belcher Group is composed of:[12][13]

- Loaf Formation (molasse)

- Omarolluk Formation (flysch)

- Flaherty Formation (flood basalt)

- Kipalu Formation (iron formation)

- Mukpollo Formation (sandstone)

- Rowatt Formation (shallow water carbonate)

- Laddie Formation (deep marine red bed)

- Costello Formation (carbonate slope deposit)

- Mavor Formation (stromatolite reef complex)

- Tukarak Formation (shallow water carbonate)

- Fairweather Formation (shallow water carbonate)

- Eskimo Formation (flood basalt)

- Kasegalik Formation (sabkha)

The oldest part of the Belcher Group, the Kasegalik Formation, was deposited between 2.0185 and 2.0154 billion years ago.[14] The Kasegalik Formation also contains the oldest unambiguous Cyanobacteria microfossils.[15] Much of the Belcher Group strata were deposited under intertidal to shallow-water conditions, although the Mavor Formation formed a platform margin stromatolite reef complex,[16] and the overlying Costello and Laddie formations represent slope and deep basin deposits, respectively.[14][16] The Kipalu Formation, deposited approximately 1.88 billion years ago, is notable for being a granular iron formation.[12][13] The Flaherty Formation basalt that composes much of the Belcher Islands was deposited between 1.87 and 1.854 billion years ago,[14] with the overlying Omarolluk and Loaf formations being deposited from 1.854 billion years ago until sometime after 1.83 billion years ago.[14][17]

Soapstone

[edit]The occurrence of very high-quality soapstone in the Belcher Islands supports a locally significant carving industry.[18] These soapstone occurrences formed when sedimentary rocks of the Belcher Group were intruded by Haig sills and dykes approximately 1.87 billion years ago.[18] Most soapstone is quarried from a site on western Tukarak Island where dolomite of the Costello Formation was intruded by hot magma,[18] with dolomite reacting with quartz and water under intense heat to form talc, calcite, and carbon dioxide:

3CaMg(CO3)2 + 4SiO2 + H2O → [Heat] Mg3Si4O10(OH)2 + 3CaCO3 + 3CO2

Other minerals within the soapstone are largely calcite, dolomite, talc, and clinochlore, with minor amounts of ilmenite.

Although most soapstone has been sourced from two quarries, the relatively widespread occurrence of Haig intrusions within the Belcher Islands suggests that there may be many more possible sources of high-quality soapstone not yet discovered.[19]

Flora

[edit]

Several species of willow (Salix) form a large component of the native small shrubbery on the archipelago. These include rock willow (Salix vestita), bog willow (S. pedicellaris), and Labrador willow (S. argyrocarpa), as well as naturally occurring hybrids between S. arctica and S. glauca.[20] Trees cannot grow on the islands because of a lack of adequate soil.[21]

Fauna

[edit]The main wildlife consists of belugas, walrus, caribou, common eiders and snowy owls all of which can be seen on the island year round. There is also a wide variety of fish that can be caught such as Arctic char, cod, capelin, lump fish, and sculpin.[22] The historical relationship between the Sanikiluaq community and the eider is the subject of a feature-length Canadian documentary film called People of a Feather. The director, cinematographer and biologist Joel Heath, spent seven years on the project, writing biological articles on the eider.[23][24]

In 1998, the Belcher Island caribou (Rangifer tarandus groenlandicus) herd numbered 800.[25]

References

[edit]- ^ "Belcher Islands". Geographical Names Data Base. Natural Resources Canada.

- ^ Issenman, Betty. Sinews of Survival: The living legacy of Inuit clothing. UBC Press, 1997. pp252-254

- ^ "Section 15, Chart Information" (PDF). pollux.nss.nima.mil. p. 322. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-11-19. Retrieved 2009-08-04.

- ^ Johnson, Martha (1 June 1998). Lore: Capturing Traditional Environmental Knowledge. DIANE Publishing. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-0-7881-7046-1. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ^ a b "History of Sanikiluaq – Past and Present". Welcome to Sanikiluaq. Hamlet of Sanikiluaq. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- ^ "Belcher Islands". Encyclopedia Britannica. Britannica. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- ^ "George Weetaltuk (ca. 1862–1956)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-24. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

- ^ Harvey, P.D.A. (1980). The History of Topographical Maps. Thames and Hudson. pp. 34–35. ISBN 0-500-24105 8.

- ^ "'At the End of the World' tells a shocking tale of murder in the Arctic". Anchorage Daily News. March 26, 2017. Retrieved 2017-12-03.

- ^ Morton, James C. (2014-03-30). "Morton's Musings: When 'God' and 'Satan' battled in a barren land; the Belcher Islands Murders". Morton's Musings. Retrieved 2017-12-03.

- ^ Baragar, W.R.A.; Scoates, R.F.J. (1981). "The Circum-Superior Belt: A Proterozoic Plate Margin?". Developments in Precambrian Geology. Elsevier. pp. 297–330. doi:10.1016/s0166-2635(08)70017-3. ISBN 978-0-444-41910-1.

- ^ a b Jackson, G D (1960). Belcher Islands, Northwest Territories 33m, 34d, and E (Report). doi:10.4095/101205.

- ^ a b Jackson, G D (2013). Geology, Belcher Islands, Nunavut (Report). doi:10.4095/292434.

- ^ a b c d Hodgskiss, Malcolm S. W.; Dagnaud, Olivia M. J.; Frost, Jamie L.; Halverson, Galen P.; Schmitz, Mark D.; Swanson-Hysell, Nicholas L.; Sperling, Erik A. (2019-08-15). "New insights on the Orosirian carbon cycle, early Cyanobacteria, and the assembly of Laurentia from the Paleoproterozoic Belcher Group". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 520: 141–152. Bibcode:2019E&PSL.520..141H. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2019.05.023. ISSN 0012-821X. S2CID 197578328.

- ^ Hofmann, H. J. (1976). "Precambrian Microflora, Belcher Islands, Canada: Significance and Systematics". Journal of Paleontology. 50 (6): 1040–1073. ISSN 0022-3360. JSTOR 1303547.

- ^ a b Ricketts, B D; Donaldson, J A (1981). Sedimentary History of the Belcher Group of Hudson Bay (Report). doi:10.4095/109371.

- ^ Corrigan, David; van Rooyen, Deanne; Wodicka, Natasha (April 2021). "Indenter tectonics in the Canadian Shield: A case study for Paleoproterozoic lower crust exhumation, orocline development, and lateral extrusion". Precambrian Research. 355: 106083. Bibcode:2021PreR..355j6083C. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2020.106083. ISSN 0301-9268. S2CID 233524866.

- ^ a b c Timlick, L. (2017). "Comparative study of the petrogenesis of excellent-quality carving stone from Korok Inlet, southern Baffin Island, and the Belcher Islands, Nunavut" (PDF). Summary of Activities – via Canada-Nunavut Geoscience Office.

- ^ Steenkamp, H.M. (2016). "Geological mapping and petrogenesis of carving stone in the Belcher Islands, Nunavut" (PDF). Summary of Activities – via Canada-Nunavut Geoscience Office.

- ^ Flora of North America. Vol. 7. Oxford University Press. 2010. pp. 64, 80, 83, 115. ISBN 978-0-19-531822-7. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ "Belcher Islands". Archived from the original on 2012-09-09. Retrieved 2009-02-12.

- ^ "Belcher Island Kayak Tour". Archived from the original on 2010-02-20. Retrieved 2009-02-12.

- ^ "People of a Feather (2011)". IMDBaccessdate=8 February 2012. 8 November 2013.

- ^ "People of a Feather". Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ^ Mallory, F.F.; Hillis, T.L. (1998), "Demographic characteristics of circumpolar caribou populations: ecotypes, ecological constraints/releases, and population dynamics", Rangifer (Special Issue 10): 9–60, retrieved 18 December 2013

Further reading

[edit]- Bell, Richard T. Report on Soapstone in the Belcher Islands, N.W.T. St. Catharines, Ont: Dept. of Geological Sciences, Brock University, 1973.

- Born, David O. "Eskimo Education and the Trauma of Social Change". Social Science Notes – 1, Northern Science Research Group, Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, Ottawa, January 15, 1970

- Caseburg, Deborah Nancy. Religious Practice and Ceremonial Clothing on the Belcher Islands, Northwest Territories. Ottawa: National Library of Canada = Bibliothèque nationale du Canada, 1994. ISBN 0-315-88029-5

- Flaherty, Robert J. The Belcher Islands of Hudson Bay Their Discovery and Exploration. Zug, Switzerland: Inter Documentation Co, 1960s.

- Fleming, Brian, and Miriam McDonald. A Nest Census and the Economic Potential of the Hudson Bay Eider in the South Belcher Islands, N.W.T. Sanikiluaq, N.W.T.: Brian Fleming and Miriam McDonald, Community Economic Planners, 1987.

- Guemple, D. Lee. Kinship Reckoning Among the Belcher Island Eskimo. Chicago: Dept. of Photoduplication, University of Chicago Library, 1966.

- Hydro-Québec, and Environmental Committee of Sanikiluaq. Community Consultation in Sanikiluaq Among the Belcher Island Inuit on the Proposed Great Whale Project. Sanikiluaq, N.W.T.: Environmental Committee, Municipality of Sanikiluaq, 1994.

- Jonkel, Charles J. The Present Status of the Polar Bear in the James Bay and Belcher Islands Area. Ottawa: Canadian Wildlife Service, 1976.

- Manning, T. H. Birds and Mammals of the Belcher, Sleeper, Ottawa and King George Islands, and Northwest Territories. Ottawa: Canadian Wildlife Service, 1976.

- Oakes, Jill E. Utilization of Eider Down by Ungava Inuit on the Belcher Islands. [Ottawa, Ont.]: Canadian Home Economics Journal, 1991.

- Richards, Horace Gardiner. Pleistocene Fossils from the Belcher Islands in Hudson Bay. Annals of the Carnegie Museum, v. 23, article 3. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Museum, 1940.

- Twomey, Arthur C., and Nigel Herrick. Needle to the North, The Story of an Expedition to Ungava and the Belcher Islands. Houghton Mifflin, 1942.