Narrow-gauge railroads in the United States

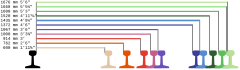

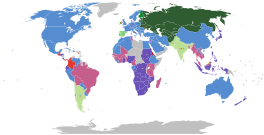

| Track gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| By transport mode | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| By size (list) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Change of gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| By location | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Standard gauge was favored for railway construction in the United States, although a fairly large narrow-gauge system developed in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado and Utah. Isolated narrow-gauge lines were built in many areas to minimize construction costs for industrial transport or resort access, and some of these lines offered common carrier service. Outside Colorado, these isolated lines evolved into regional narrow-gauge systems in Maine, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Iowa, Hawaii, and Alaska.

New England

[edit]

In New England, the first narrow-gauge common-carrier railroad was the Billerica and Bedford Railroad, which ran from North Billerica to Bedford in Middlesex County, Massachusetts from 1877 to 1878. There were extensive 2 ft (610 mm) gauge lines in the Maine forests early in the 20th century. In addition to hauling timber, agricultural products and slate, the Maine lines also offered passenger services. The Boston, Revere Beach & Lynn Railroad was a narrow-gauge commuter railroad that operated in Massachusetts, much of whose right-of-way is used for rapid transit today. Narrow gauges also operated in the mountains of New Hampshire, on the islands of Nantucket and Martha's Vineyard and in a variety of other locations. The still-operating Edaville Railroad tourist heritage railroad in southeastern Massachusetts is a two-foot narrow-gauge system.

Mid-Atlantic

[edit]

The last remaining 3 ft (914 mm) gauge common carrier east of the Rocky Mountains was the East Broad Top Railroad in central Pennsylvania. Running from 1873 until 1956, it supplied coal to brick kilns and general freight to the towns it passed through, connecting to the Pennsylvania Railroad at Mount Union, Pennsylvania. Purchased for scrap by the Kovalchick Corporation when it ended common carrier service in 1956, it reopened as a tourist railroad in 1960. This line is the oldest surviving stretch of narrow-gauge track in the United States. Financial troubles would force the Kovalchick family to close the railroad following the 2011 season. The railroad sat dormant until 2020 when it was purchased and reopened by the EBT Foundation.[1]

It was the last remnant of an extensive narrow-gauge network in New York and Pennsylvania that included many interconnecting lines. The largest concentration was in the Big Level region around Bradford, Pennsylvania, from which lines radiated towards Pittsburgh and into New York state. This group also included the Tonawanda Valley & Cuba Railroad. Though the TV&C's narrow-gauge tracks are long gone, the standard-gauge Arcade and Attica Railroad continues to run over a portion of the TV&C's route. The Waynesburg and Washington Railroad, a subsidiary of the Pennsylvania Railroad, operated in the southwestern part of the state until 1933.

The Philadelphia and Atlantic City Railway and the Pleasantville & Ocean City Railroad were originally built to 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauge.

Southeast

[edit]The Southeast helped initiate the narrow-gauge era. The first in Georgia was the Kingsboro & Cataula Railway, chartered in 1870.[2] In Tennessee, the Duck River Valley Narrow Gauge Railway was also chartered in 1870, opening seven years later; it was converted to standard gauge in 1888. The first narrow-gauge railway in Alabama was the Tuskegee Railroad in 1871.

Longest lived of its narrow gauges was the East Tennessee and Western North Carolina Railroad. Originally built as a broad gauge [which?] [citation needed] in 1866, the line was later converted to a narrow-gauge railroad between Johnson City, Tennessee; Cranberry, North Carolina; and ultimately Boone, North Carolina. It continued in service until 1950.

Another long-lived southern narrow gauge was the Lawndale Railway and Industrial Co.

Midwest

[edit]One of the first three narrow gauges in the U.S. – the Painesville & Youngstown – opened in Ohio in 1871, and the narrow-gauge movement reached its greatest length in the Midwest. For a brief time in the 1880s it was possible to travel by narrow gauge from Lake Erie across the Mississippi River and into Texas. The hub of this system, Delphos, Ohio, shared with Durango, Colorado the distinction of being the only towns in the United States from which it was possible to travel by narrow gauge in all four compass directions.

The Chicago Tunnel Company operated a 60-mile (97 km) long underground 2 ft (610 mm) gauge freight railroad under the streets of the Chicago Loop. This common carrier railroad used electric traction, interchanged freight with all of the railroads serving Chicago, and offered direct connections to many loop businesses from 1906 to 1959.

Ohio was a center of the narrow-gauge movement. In addition to serving as the northern end of the Little Giant "transcontinental", it had several other notable lines, including the long-lived Ohio River & Western Railroad, the Kelley Island Lime & Transport Company (the world's largest operator of Shay locomotives, virtually all of them narrow gauge) and the Connotton Valley Railroad, a successful coal hauler still in operation today as the standard-gauge Wheeling & Lake Erie Railroad. Narrow gauge railroad mileage in Ohio reached its peak in 1883 and declined rapidly after 1884.[3]

Numerous 3 ft (914 mm) gauge common-carrier narrow-gauge lines were built in Iowa in the 19th century. The largest cluster of lines radiated from Des Moines, with the Des Moines, Osceola and Southern extending south to Cainsville, Missouri, the Des Moines North-Western extending northwest to Fonda and smaller lines extending north to Boone and Ames. These lines were all abandoned or regauged by 1900. The Burlington and Western and the Burlington and Northwestern system extended from Burlington to Washington, Iowa and the coal fields around Oskaloosa. This system was widened to standard gauge on June 29, 1902 and merged with the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad a year later. The Bellevue and Cascade, from Bellevue on the Mississippi to Cascade inland remained in service until abandonment in 1936. A caboose from the Bellevue and Cascade is the only surviving piece of Iowa narrow-gauge equipment. It currently operates on the Midwest Central Railroad in Mount Pleasant, a heritage railroad.

In 1882, thirty-two narrow-gauge logging railroads were constructed in Michigan, and by 1889 there were eighty-nine such logging railroads in operation, totaling almost 450 miles (720 km) of track.[4]

Mountain West

[edit]

At its peak, the mountain west region had a narrow gauge system which stretched from Montana to New Mexico; with the majority of routes operating out of central hubs in Colorado and Utah.

The Denver and Rio Grande Railroad, opened in 1871, was one of the earliest narrow gauge railroads in the United States and by far the longest and one of the most significant. The railroad's founder William Jackson Palmer during the early planning stages of the railroad in 1871 visited the Ffestiniog Railway in Wales while on his honeymoon, and while in the United Kingdom consulted with Scottish engineer Robert Francis Fairlie who convinced Palmer of the advantages of building the Rio Grande using narrow gauge.[5]

The Rio Grande effectively circled the state of Colorado, and feeder lines were run to the mining communities of Leadville, Aspen, Cripple Creek, Telluride and Silverton. The Rio Grande would find itself in a railroad war with the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway in 1878 from 1880 for control over the Royal Gorge canyon.[6] The conflict would be settled by "The Treaty of Boston" in 1880, allowing the Rio Grande to continue building east towards Leadville and towards Grand Junction through the Black Canyon of the Gunnison. Through affiliated companies, the Rio Grande's lines would extended west to Ogden, Utah and south to Santa Fe, New Mexico.

The Rio Grande mainline was gradually re-gauged after it and the Colorado Midland Railway built a new standard gauge joint line to Grand Junction in 1890, but the southern portions remained steam-hauled and narrow gauge into the mid 20th century.[7] This southern segment would be advertised as the "Narrow Gauge Circle" which via a connection with the Rio Grande Southern (which was among various narrow gauge railroads connecting with the larger Denver & Rio Grande which had been built by Otto Mears) allowed travelers to make a continuous journey through the southwestern corner of Colorado onboard narrow gauge trains.[8] The cash strapped Rio Grande Southern would build a fleet of Galloping Goose cars to preserve the mail contract along their route from the 1930's until the lines abandonment in 1952.[9]

As remaining segments of the Denver & Rio Grande Western's narrow gauge system were abandoned through-out Colorado in the mid-20th century, the San Juan Extension experienced a reprieve with the petroleum industry booming from the 1950's into the 1960's around Farmington, New Mexico.[10] As traffic from the oil boom subsided, the Denver & Rio Grande Western abandoned the narrow gauge from Durango, Colorado to Chama, New Mexico; and the Chama to Antonito, Colorado portion of the line was jointly purchased by the states of Colorado and New Mexico to form the Cumbres and Toltec Scenic Railroad in 1970.

Tourism increased along the Silverton branch following World War II, and the area was popularized through Western films which frequently filmed along the San Juan Extension and the railroad became a popular road trip destination.[11] Unable to abandon the Silverton branch, the D&RGW operated it as an isolated narrow gauge and steam powered route until 1981 when the line was sold and rebranded as the Durango and Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad.

Operations of the Durango & Silverton and the Cumbres & Toltec have both been impacted by the ongoing Southwestern North American megadrought and fuel availability. The Durango & Silverton was closed by the Missionary Ridge Fire in 2002 marking the first time the railroad would be closed by fire danger in its history.[12] In 2018 the railroad would close again due to the 416 Fire which was attributed to having been caused by the railroad, leading to a lawsuit against the railroad from the Federal Government to recoup fire fighting costs which would be settled with a $20 million dollar fine against the Durango & Silverton.[13] The Durango & Silverton would phase out coal fired steam locomotives, converting their steam locomotive fleet to burn oil to reduce embers, running their final coal fired train in early 2024.[14] Both the Durango & Silverton and Cumbres & Toltec would purchase diesel locomotives from the White Pass and Yukon Route to provide alternative power to steam locomotives during high fire risk seasons and as emergency backups to traditional steam locomotives.[15][16]

Other major narrow-gauge railroads in Colorado included the Denver, South Park and Pacific, the Colorado Central, and the Florence and Cripple Creek. The Uintah Railway operated in Utah and Colorado, and boasted the tightest curve (Moro Castle curve) on a US common carrier at Baxter Pass.[17] Some short segments of narrow gauge railroads have been rebuilt in Colorado as heritage railroads with the Georgetown Loop Railroad opening in 1973 and the Como Roundhouse having been initially restored and expanded since 1984.[18][19] The Colorado Railroad Museum established in 1959, operates a demonstration loop of narrow gauge track in Golden, Colorado.[20]

In Utah, three foot gauge narrow-gauge railroads sprang up immediately after the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad on May 10, 1869. An 1870 article published by the Deseret News reported on the international success of the Ffestiniog and promoted narrow gauge as viable for the Utah territory.[21] The Utah and Northern Railway connected the fertile Mormon Corridor with the mining camps near Butte, Montana with an extensive three-foot gauge system that lasted from 1871 until 1887.[22] John Willard Young was a primary investor and owner of many of the territory's narrow gauge lines including the early Utah Northern; and competed with the established standard gauge Union Pacific Railroad and Central Pacific Railroad routes in the region.[23] Robber baron Jay Gould would take control of the Utah and Northern by 1877 bringing it under the control of Union Pacific as the line was extended from Idaho to Montana.[24] The American Fork Railroad was the first railroad to use a Mason Bogie locomotive an articulated design derived from the British Single Fairlie locomotive. Other narrow-gauge lines in Utah included the Wasatch & Jordan Valley (which hauled granite for the construction of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saint's Salt Lake City temple) and the Utah & Pleasant Valley which tapped into the Pleasant Valley coal fields in north-central Utah. Both of these later railroads eventually formed part of the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railway a Utah based extension of the Rio Grande network, which connected the Utah narrow gauge to Colorado.[25] Other narrow gauge routes in Utah were later absorbed by the Union Pacific and its subsidiaries. Union Pacific made use of Ramsey car transfers through-out Utah and Idaho to account for gauge changes in the region.[26][27]

Connections from the Utah narrow gauge railroads to those in Colorado was severed in 1890 when the then independent Rio Grande Western regauged their mainline from Ogden, Utah to Grande Junction.[28] The Oregon Short Line Railroad regauged the former Utah and Northern in 1890 as well, isolating a few surviving narrow gauge lines to the immediate area around the Wasatch Front.[29] The surviving pockets of narrow gauge in the Wasatch Front continued until the Oregon Short Line Railroad built a standard gauge route through Bauer, Utah in 1903; and the Little Cottonwood Transportation Co. (which operated leased track from the Rio Grande on the former Wasatch & Jordan Valley) ended service in 1925.[30][31] Narrow gauge in the state continued with isolated lines serving mining regions such as the Eureka Hill Railway which served the Tintic mining district until 1937, and along the Utah-Colorado border on the Uintah Railway which operated until 1939.[32] A two foot gauge railroad in Utah, the Bingham Central Railway; which was mostly underground through the Mascote Tunnnel, operated as a common carrier railroad when founded in 1908 before becoming a private operation which would close in the 1950's when replaced by a new tunnel.[33]

Narrow gauge railroads served mining districts through central and eastern Nevada, such as the Eureka and Palisade Railroad and the Nevada Central Railroad. Some projects would have connected the Nevada narrow gauge network to the lines in Utah & Colorado, such as early projections for the Salt Lake, Sevier Valley & Pioche Railroad which would have connected with other narrow gauge lines at Pioche, Nevada; however none of these railroads were successful in reaching their initial goals.[34] Locomotives from these central Nevada lines such as Eureka and Nevada Central #2 (renamed to the "Emma Nevada" by former owner and Disney animator Ward Kimball) survive to the present.

West Coast

[edit]

The Southern Pacific operated several 3 ft (914 mm) gauge railroads, including the Carson and Colorado Railway and the Nevada–California–Oregon Railway, running from Reno into southern Oregon. California's independent 3 ft (914 mm) lines included the Pacific Coast Railway serving the Santa Maria Valley, the North Pacific Coast Railroad and South Pacific Coast Railroads extending northward and southward from San Francisco Bay, and the surviving Disneyland Railroad.

The defunct Arcata and Mad River Railroad was 3 ft 9+1⁄2 in (1,156 mm) gauge

Two small regional railways in the Pacific Northwest were the Ilwaco Railway and Navigation Co near Astoria, and the Sumpter Valley Railway near Baker City, Oregon. The latter still operates in the summer.

The San Francisco cable car system is 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauge as was the now defunct Los Angeles Railway and the San Diego Electric Railway.

Alaska

[edit]Alaska is home to two surviving narrow gauge railroads. The last surviving commercial common carrier narrow-gauge railroad in the United States was the White Pass and Yukon Route connecting Skagway, Alaska and Whitehorse, Yukon Territory. It ended common carrier service in 1982, but has since been partially reopened as a tourist railway.

The Second is in the interior of Alaska, in Fairbanks. A narrow gauge railroad known as the Tanana Valley Railroad, was bought by the Alaska Railroad in 1930, when the transition of narrow gauge to standard gauge happened. Today, the Tanana Valley Railroad steam locomotive Engine No. 1 is still operated by the Friends of the Tanana Valley Railroad and housed in the Tanana Valley Railroad Museum which is open year-round. The steam locomotive is taken out and fired up during the summer on a scheduled basis.

Hawaii

[edit]Hawaii boasted an extensive network of not only narrow-gauge sugar-cane railways, but common carriers such as the Hawaii Consolidated Railway (which was standard gauge), Ahukini Terminal & Railway Company, Koolau Railway company, Kahului Railroad, and the Oahu Railway and Land Company. The Oahu Railway and Land Company was the largest narrow-gauge class-one common-carrier railway in the US (at the time of its dissolution in 1947), and the only US narrow-gauge railroad to use signals. The OR&L used Automatic Block Signals, or ABS on their double track mainline between Honolulu and Waipahu, a total of 12.9 miles (20.8 km), and had signals on a branch line for another nine miles (14 km). The section of track from Honolulu to Waipahu saw upwards of eighty trains a day, making it not only one of the busiest narrow-gauge main lines in the U.S, but one of the busiest mainlines in the world.

Other applications of narrow gauge in the U.S.

[edit]There were also numerous narrow-gauge logging railroads in Pennsylvania and West Virginia who operated mostly with geared locomotives such as Shays, Climaxes, and Heislers.

Many narrow-gauge lines were private carriers serving particular industries. One major industry that made extensive use of 3 ft (914 mm) gauge railroads was the logging industry, especially in the West. Although most of these lines closed by the 1950s, one notable later survivor was West Side Lumber Company railway which continued using 3 ft (914 mm) gauge geared steam locomotives until 1968.

There is one narrow-gauge industrial railroad still in commercial operation in the United States, the US Gypsum operation in Plaster City, California, which uses a number of Montreal Locomotive Works locomotives obtained from the White Pass after its 1982 closure. Temporary narrow-gauge railways are commonly built to support large tunneling and mining operations.

The famous San Francisco cable car system has a gauge of 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm), as did the street cars on the former Los Angeles street railway.

Rail haulage has been very important in the mining industry. By 1922, 80 percent of all new coal mines in the United States were being developed using 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) (42 inch) gauge trackage, and the American Mining Congress recommended this as a standard gauge for coal mines, using a 42-inch (1,067 mm) wheelbase and automatic couplers [which?] centered 10 inches (254 mm) above the rail.[35]

The Washington Metro system in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area has a gauge of 4 ft 8+1⁄4 in (1,429 mm), which is 1/4" or 6mm closer than standard gauge.

U.S. common-carrier narrow gauges in the twentieth century

[edit]Thousands of narrow-gauge railroads were built or projected in the U.S. The following list includes those common-carrier narrow-gauge railroads which operated into the twentieth century. Note: this list intentionally excludes tourist railroads, amusement parks, loggers, and other non-common carriers.

Narrow-gauge railroad displays

[edit]Some cars and trains from the Maine two-footers are now on display at the Maine Narrow Gauge Railroad Museum in Portland, Maine.

In 1957, the East Tennessee and Western North Carolina Railroad was revived as a tourist attraction under the common name, Tweetsie Railroad. It currently runs a three-mile (5 km) route near Blowing Rock, North Carolina. Similarly, the East Broad Top Railroad was revived in 1960 and runs on three miles of original 1873 trackage.

Significant remnants of the Colorado system remain as tourist attractions which run in the summer, including the Cumbres and Toltec Scenic Railroad running between Antonito, CO in the San Luis Valley and Chama, NM, and the Durango and Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad running between its namesake towns of Durango and Silverton in the San Juan Mountains. Another line is the Georgetown Loop Railroad between Georgetown, Colorado and Silver Plume, Colorado in central Colorado. Much equipment from the Colorado narrow gauges is on display at the Colorado Railroad Museum in Golden, Colorado. Many pieces of the D&RGW's narrow-gauge equipment were sold off to various other companies upon its abandonment; the Ghost Town & Calico Railroad, a heritage railroad at Knott's Berry Farm in California, operates passenger service daily with two Class C-19 Consolidation (2-8-0) locomotives hauling preserved coaches along with a famed Galloping Goose RGS #3. D&RGW 223, a C-16 steam locomotive, is undergoing restoration at the Utah State Railroad Museum in Ogden, Utah.[51]

Much of the equipment from the Westside Lumber Co. found its way to tourist lines, including the Roaring Camp & Big Trees Narrow Gauge Railroad and Yosemite Mountain Sugar Pine Railroad in California and the Midwest Central Railroad in Iowa. Additional equipment from the west coast narrow gauges is displayed at the Nevada County Narrow Gauge RR Museum, in Nevada City, CA, Laws Depot Museum, and at the Grizzly Flats Railroad (donated to Southern California Railway Museum after Ward Kimball's death) along with a Westside Lumber caboose.

The Huckleberry Railroad in Flint, Michigan began operating in 1976 using a part of an old Flint & Pere Marquette Railroad branch line. The Flint & Pere Marquette Railroad extended the branch line from Flint to Otter Lake in the late 1800s. It later came to be known as the Otter Lake Branch. Eventually the track was extended by another 4.5 miles from Otter Lake to Fostoria, for a total of 19.5 miles from Flint to Fostoria. The Pere Marquette Railway abandoned the Flint to Fostoria branch line in 1932. The Huckleberry Railroad began operations in 1976 on the remaining section of the Flint to Fostoria line when the Genesee County Parks and Recreation Commission purchased the line and opened Crossroads Village & Huckleberry Railroad as a historical tourist attraction.

Meanwhile, in Hawaii, the Hawaiian Railway Society on the island of Oahu operates on 6 miles of remaining Oahu Railway and Land Company trackage, from the yard in Ewa to Nanakuli. More tracks remain past a burned down bridge, and past the society in Ewa, totaling to 12 miles of remaining OR&L Right of way. On Maui, the Lahaina, Kaanapali and Pacific Railroad operates on 6 miles of tracks through former sugar plantation land. This railroad, also known as the "Sugar Cane Train" is the only 3 foot railroad in Hawaii to operate steam locomotives. On Kauai, two narrow-gauge railroads still operate. The 3 foot railroad, the Kauai Plantation Railway operates on a 3-mile loop through the Kilohana Estate and Plantation. The second narrow-gauge railroad on Kauai is a 30-inch railway, the Grove Farm Sugar Plantation Museum. They operate many different locomotives, from steam to diesel, on a mile loop through parts of the former Lihue Plantation.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Orwoll, Mark (March 12, 2024). "Save the Rails". saturdayeveningpost.com. The Saturday Evening Post. Retrieved January 18, 2025.

- ^ Seibert, David. "Kingsboro & Cataula". GeorgiaInfo: an Online Georgia Almanac. Digital Library of Georgia. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ Various editions of the Annual Report of the Commissioner of Railroads and TeIegraphs to the Governor of the State of Ohio. State of Ohio.

- ^ Maybee 1976, p. 41

- ^ Jones, Chris; Lewin, Paul; Dobson, John (March 2012). "WELSH PONY CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN" (PDF). festrail.co.uk. Ffestiniog & Welsh Highland Railways. Retrieved December 12, 2024.

- ^ "A war between railroads". royalgorgeroute.com. Canon City, Colorado: Royal Gorge Route Railroad. Retrieved January 12, 2025.

- ^ Holmes, Nathahn (January 12, 2008). "Rio Grande Junction Railway". drgw.net. DRGW.net. Retrieved December 13, 2024.

- ^ Iverson, Lucas (December 15, 2024). "Reminiscing on five prolific narrow gauge railroads in Colorado". trains.com. Firecrown Media. Retrieved January 18, 2025.

- ^ "A Short History of the Rio Grande Southern Railroad & The Galloping Goose". gallopinggoose5.org. Ridgeway, Colorado: Galloping Goose Historical Society. Retrieved January 18, 2025.

- ^ Holmes, Nathan. "San Juan Extension - Farmington Branch". drgw.net. Retrieved January 18, 2025.

- ^ Holmes, Nathan. "Silverton Branch". drgw.net. Retrieved January 18, 2025.

- ^ "Fire Causing Major Losses for Silverton-Durango Train". Kingman Daily Miner. Associated Press. August 26, 2002. Retrieved January 18, 2025.

- ^ Tabachnik, Sam (March 22, 2022). "Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad to pay feds $20 million over 416 fire". denverpost.com. Denver, Colorado: The Denver Post.

- ^ "Durango & Silverton Runs Final Coal-Powered Steam Excursion". railfan.com. White River Productions. March 25, 2024. Retrieved January 18, 2025.

- ^ Romeo, Jonathan (April 15, 2020). "Durango railroad purchases four diesel locomotives". durangoherald.com. Durango, Colorado: Durango Herald. Retrieved January 18, 2025.

- ^ Franz, Justin (November 14, 2023). "Cumbres & Toltec to Purchase White Pass Diesel". railfan.com. White River Productions. Retrieved January 18, 2025.

- ^ Walker 1995, p. 9

- ^ "Our History". georgetownlooprr.com. Georgetown Loop Railroad. 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ^ Kazel, Bill; Kazel, Greg; Brantigan, Chuck. "Como Roundhouse History". 2023. South Park Rail Society. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ^ "History & TIMELINE". coloradorailroadmuseum.org. Colorado Railroad Museum. 2024. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ^ "Deseret News | 1870-05-25 | Page 1 | Narrow Guage for Railroads". newspapers.lib.utah.edu. Retrieved 2024-12-12.

- ^ Carr, Stephen L. (1989). Utah Ghost Rails. Salt Lake City Utah: Western Epics. pp. 19–20. ISBN 0-914740-34-2.

- ^ Nicholas, David (December 9, 2020). "Salvation – J.W. Young Brings the Rail". parkcityhistory.org. Park City Museum. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ^ Strack, Don (November 21, 2024). "Utah & Northern Railway (1878-1889)". utahrails.net. Utah Rails. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ^ Strack, Don (January 27, 2024). "Denver & Rio Grande Western Railway (1881-1889)". utahrails.net. Utah Rails. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ^ Waite, Thornton (2012). The Railroad at Pocatello. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-7385-7617-6.

- ^ Franzen, John (January 1981). Southeastern Idaho, Cultural Resources Overview Burley and Idaho Falls Districts (Report). Department of the Interior. p. 156. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ^ "Rio Grande Western, Standard Gauged (1890)". utahrails.net. The Railroad Gazette. 1890. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ^ Strack, Don (September 26, 2024). "Oregon Short Line History, 1981". utahrails.net. Utah Rails. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ^ Strack, Don (June 18, 2022). "Leamington Cutoff". utahrails.net. Utah Rails. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ^ Strack, Don (April 23, 2019). "Little Cottonwood Transportation Company (1916-1922) Alta Scenic Railway (1925)". utahrails.net. Utah Rails. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ^ Strack, Don (February 4, 2021). "Eureka Hill Railway (1907-1937)". utahrails.net. Utah Rails. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ^ Strack, Don (August 13, 2024). "Mascotte Tunnel / Bingham Central Railway". Retrieved December 12, 2024.

- ^ Strack, Don (July 22, 2020). "Utah Western Railway (1874-1881)".

- ^ Stoek, Fleming & Hoskin 1922, pp. 103–103

- ^ Hilton 1990, p. 484

- ^ Hilton 1990, p. 302

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 309–310

- ^ Hilton 1990, p. 310

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 313–314

- ^ a b c Hilton p. 314

- ^ Hilton 1990, p. 394

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 416–418

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 507–508

- ^ Hilton 1990, p. 407

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 438–440

- ^ a b c Hilton 1990, pp. 452–453

- ^ Various Annual Reports of the Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs to the Governor of the State of Ohio, esp. for the Years 1877, 1901 and 1902. Google books, HathiTrust: State of Ohio.

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 340–342

- ^ Hilton 1990, p. 311

- ^ a b c d e Strack, Don. "Utah Railroads". Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 344–353

- ^ Hilton 1990, p. 486

- ^ Hilton 1990, p. 302–304

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 486–488

- ^ a b Hilton 1990, pp. 516–519

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 441–442

- ^ Hilton 1990, p. 543

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 358–359

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 410–411

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 387–389

- ^ Hilton 1990, p. 305

- ^ Hilton 1990, p. 488

- ^ Hilton 1990, p. 409

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 488–490

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 459–461

- ^ a b Hilton 1990, p. 490

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 311–312

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 414–416

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 409–410

- ^ a b c Hilton 1990, p. 304

- ^ Hilton 1990, p. 312

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 490–492

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 419–420

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 326–328

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 442–443

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 328–329

- ^ Hilton 1990, p. 443

- ^ Hilton 1990, p. 492

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 492–493

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 329–330

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 380–381

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 470–471

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 480–481

- ^ Westcott & Johnson 1998

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 332–333

- ^ Hilton 1990, p. 411

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 443–444

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 493–494

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 494–497

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 5–5

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 360–362

- ^ Hilton 1990, p. 410

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 410–413

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 312–313

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 335–337

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 481–483

- ^ Hilton 1990, p. 499

- ^ Hilton 1990, p. 306

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 499–501

- ^ Hilton 1990, p. 444

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 501–502

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 304–305

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 363–366

- ^ Hilton 1990, p. 313

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 502–503

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 306–309

- ^ "White Pass & Yukon Route Railway | Scenic Railway of the World". wpyr.com. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 305–306

- ^ Hilton 1990, pp. 413–414

References

[edit]- Hilton, George W. (1990). American Narrow Gauge Railroads. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2369-9.

- Maybee, Rolland (1976). Michigan White Pine Era. Lansing, MI: Michigan Historical Commission.

- Stoek, H. H.; Fleming, J. R.; Hoskin, A. J. (July 31, 1922). "A Study of Coal Mine Haulage in Illinois". University of Illinois Bulletin. XIX (49).

- Walker, Mike (1995). Steam Powered Video's comprehensive railroad atlas of North America. Nr. Faversham, [England]: Steam Powered Publishing. ISBN 1-8747-4503-X.

- Westcott, Kenneth E.; Johnson, Curtiss H. (1998). The Pacific Coast Railway: Central California's Premier Narrow Gauge. Los Altos, CA: Benchmark Publications. ISBN 978-0-9615-4674-8.

- Carr, Stephen L. (1989). Utah Ghost Rails. Salt Lake City, Utah: Western Epics.