Nancy Green

Nancy Green | |

|---|---|

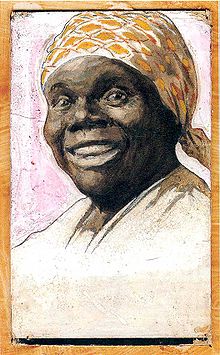

Portrait of Green as Aunt Jemima | |

| Born | March 4, 1834 Mount Sterling, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | August 30, 1923 (aged 89) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Nanny, cook, model |

| Known for | Aunt Jemima |

Nancy Green (March 4, 1834 – August 30, 1923) was an American former slave, who, as "Aunt Jemima", was one of the first African-American models hired to promote a corporate trademark. The Aunt Jemima recipe was not her recipe, but she became the advertising world's first living trademark.[1]

Biography

[edit]Nancy Hayes (or Hughes) was born enslaved in the Antebellum South on March 4, 1834.[2] Montgomery County Historical Society oral history places her birth at a farm on Somerset Creek, six miles outside Mount Sterling in Montgomery County, Kentucky. With George Green, she had at least two and as many as four children (one of whom was born in 1862). Local farmers from that area named Green raised tobacco, hay, cattle, and hogs. There were no birth certificates or marriage licenses for enslaved people.[3][4][5]

Nancy Green has been variously described as a servant, nurse, nanny, housekeeper, and cook for Samuel Johnson Walker and his wife Amanda.[6][2][4][5][7] She also served the family's next generation, again as a nanny and a cook. Walker's two sons later became well known as Chicago Circuit Judge Charles Morehead Walker., and Dr. Samuel J. Walker.[6][5][7]

By the end of the American Civil War, Green had already lost her husband and children. She lived in a wood frame shack (still standing as of 2014) behind a grand home on Main Street in Covington, Kentucky.[2][4] She moved with the Walkers from Kentucky to Chicago in the early 1870s, before the birth of Samuel's youngest child in 1872.[7] The Walker family initially settled in a swank residential district near Ashland Avenue and Washington Boulevard called the "Kentucky Colony", then home to many transplanted Kentuckians.[7]

On the recommendation of Judge Walker,[8] she was hired by the R.T. Davis Milling Company in St. Joseph, Missouri, to represent "Aunt Jemima", an advertising character named after a song from a minstrel show. According to Maurice M. Manring, the company's search for "A real living black woman, instead of a white man in blackface and drag, would reinforce the product's authenticity and origin as the creation of a real ex-slave."[9]

At the age of fifty-nine, Green made her debut as Aunt Jemima at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition held in Chicago, beside the "world's largest flour barrel" (twenty-four feet high), where she operated a pancake-cooking display, sang songs, and promoted the product. [8][10][11][12]

After the Expo, Green was reportedly offered a lifetime contract to adopt the Aunt Jemima moniker and promote the pancake mix; however, she would only choose to serve in the position for twenty years.[1][13] This marked the beginning of a major promotional push by the company that included thousands of personal appearances and Aunt Jemima merchandising. She appeared at fairs, festivals, flea markets, food shows, and local grocery stores. Her arrival was heralded by large billboards featuring the caption, "I's in town, honey."[8][12]

Despite her "lifetime contract", she portrayed the role for no more than twenty years.[6][10] She refused to cross the ocean for the 1900 Paris exhibition.[6][10][14] She was replaced by Agnes Moodey, deemed by the company to be "a Negress of sixty years".[15] After Green's death other women were hired by Quaker Oats to portray the role of Aunt Jemima, including Lillian Richard.[16]

In 1910, at age 76, Green was still working as a residential housekeeper according to the census.[7][10][13]

Few people were aware of her role as Aunt Jemima.[13] Green lived with nieces and nephews in Chicago's Fuller Park and Grand Boulevard neighborhoods into her old age.[7] At the time of her death, she was living with her great-nephew and his wife.[14]

Religion and advocacy

[edit]Green was active in the Chicago Olivet Baptist Church.[6][7][8] During her lifetime, it grew significantly, becoming the largest African-American church in the United States, with a membership at that time of over 9,000.[6][17]

Her stature as a national spokesperson enabled her to become an advocate against poverty and in favor of equal rights for the black population. She used her stature as a spokesperson to advocate against poverty and in favor of equal rights for individuals in Chicago.[1][18]

Death

[edit]Green died on August 30, 1923, at the age of 89 in Chicago, when a car driven by pharmacist Dr. H. S. Seymour collided with a laundry truck and "hurtled" onto the sidewalk where she was standing.[6][7][19][20][21] She is buried in a pauper's grave near a wall in the northeast quadrant of Chicago's Oak Woods Cemetery.[19][22]

Grave marker

[edit]Her grave was unmarked and unknown until 2015.[7] Sherry Williams, founder of the Bronzeville Historical Society, spent 15 years uncovering Green's resting place.[14][22] Williams received approval to place a headstone.[22] Williams reached out to Quaker Oats about whether they would support a monument for Green's grave. "Their corporate response was that Nancy Green and Aunt Jemima aren't the same – that Aunt Jemima is a fictitious character."[14] The headstone was placed on September 5, 2020.[23][24]

Lawsuit

[edit]In 2014, a lawsuit was filed against Quaker Oats, PepsiCo, and others, claiming that Green and Anna Short Harrington (who portrayed Aunt Jemima starting in 1935) were exploited by the company and cheated out of the monetary compensation they were promised. The plaintiffs were two of Harrington's great-grandsons, and they sought a multi-billion dollar settlement for descendants of Green and Harrington.[25] The lawsuit was dismissed with prejudice and without leave to amend on February 18, 2015.[26]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Nancy Green, the original "Aunt Jemima"". aaregistry.org. 2005. Retrieved 2020-06-19.

She was a Black storyteller and one of the first (Black) corporate models in the United States. Nancy Green was born a slave in Montgomery County, Kentucky.

- ^ a b c Turley, Alicestyne (June 25, 2020). "The real story behind 'Aunt Jemima,' and a woman born enslaved in Mt. Sterling, Kentucky". Lexington Herald-Leader. Retrieved 2020-06-25.

- ^ Eblen, Tom (February 8, 2012). "New location fitting for black history museum". Lexington Herald-Leader. Retrieved 2020-06-22.

- ^ a b c Downs, Jere (October 7, 2014). "Pancake flap: Aunt Jemima heirs seek dough". Louisville Courier Journal. Retrieved 2020-06-25.

- ^ a b c Roberts, Sam (July 18, 2020). "Overlooked No More: Nancy Green, the 'Real Aunt Jemima'". New York Times. Retrieved 2020-07-18.

- ^ a b c d e f g

"'Aunt Jemima' of Pancake Fame Is Killed by Auto". Chicago Daily Tribune. September 4, 1923. p. 13. Retrieved 2020-06-19 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hansen, John Mark (June 19, 2020). "The real stories of the Chicago women who portrayed Aunt Jemima". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2020-06-22.

- ^ a b c d Kern-Foxworth, Marilyn (1994). Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben and Rastus: Blacks in advertising, Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow: Public Relations Review. Vol. 16 (Fall):59. Connecticut and London: Greenwood Press. Archived from the original on 2014-04-24.

- ^ Manring, Maurice M. (1998). Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0-8139-1811-1.

- ^ a b c d Witt, Doris (2004). Black Hunger: Soul Food and America. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-4551-0.

- ^ Wallace-Sanders, Kimberly (2008). "Dishing Up Dixie: Recycling the Old South". Mammy: A Century of Race, Gender, and Southern Memory. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. pp. 58–72. ISBN 978-0-472-11614-0. OCLC 185123470.

- ^ a b "Caricatures of African Americans: Mammy". Regnery Publishing. November 25, 2012. Archived from the original on 2020-06-22. Retrieved 2020-06-19.

- ^ a b c McElya, Micki (2007). Clinging to mammy: the faithful slave in twentieth-century America. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-04079-3. OCLC 433147574.

- ^ a b c d Nagasawa, Katherine (June 19, 2020). "The Fight To Preserve The Legacy Of Nancy Green, The Chicago Woman Who Played The Original 'Aunt Jemima'". WBEZ. Retrieved 2020-06-22.

- ^

""Aunt Jemima" Back: Famous Baker of Hoe Cakes Returns from Her Service in Corn Kitchen of Paris Exposition"". Independence Daily Reporter. Independence, Kansas. December 3, 1900. p. 4. Retrieved 2020-06-24 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Scholosberg, Jon; Roberts, Deborah (August 12, 2020). "The untold story of the real 'Aunt Jemima' and the fight to preserve her legacy". ABC News. Retrieved 2024-02-29.

- ^ Best, Wallace. "Olivet Baptist Church". Encyclopedia of Chicago. Retrieved 2019-09-11.

- ^ Roberts, Diane (1994). The Myth of Aunt Jemima: Representations of Race and Region. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-04918-0.

- ^ a b "Death Notices". Chicago Daily Tribune. August 31, 1923. p. 10.

- ^ "Pan-Cake 'Mammy' Is Dead". Chicago Daily News. August 31, 1923. p. 4.

- ^ ""Aunt Jemima" of Pancake Fame, Dead". The Sunday Morning Star. September 9, 1923. p. 17. Retrieved 2020-07-17.

- ^ a b c Crowther, Linnea (June 19, 2020). "Finally, a proper headstone for the original Aunt Jemima spokeswoman, Nancy Green". legacy.com. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ Gibson, Tammy (August 31, 2020). "Nancy Green, the Original face of Aunt Jemima, Receives a Headstone". The Chicago Defender. Retrieved 2020-11-09.

- ^ Johnson, Erick (September 15, 2020). "Nearly 100 years later, original Aunt Jemima gets a headstone". The Chicago Crusader. Archived from the original on 2020-11-11. Retrieved 2020-09-22.

- ^ "Aunt Jemima Might Have Been Real, and Her Descendants Are Suing for $2 Billion". TakePart. Archived from the original on 2019-02-28. Retrieved 2019-02-27.

- ^ "'Aunt Jemima' Heirs' $3B Royalties Suit Against Pepsi Axed". law360.com.

- 1834 births

- 1923 deaths

- 19th-century American slaves

- 19th-century Baptists

- 20th-century African-American people

- 19th-century African-American women

- 20th-century African-American women

- Aunt Jemima

- African-American activists

- Baptists from Illinois

- Female characters in advertising

- Pedestrian road incident deaths

- People from Montgomery County, Kentucky

- Quaker Oats Company people

- Road incident deaths in Illinois

- People enslaved in Kentucky