Nabataean religion

The Nabataean religion was a form of Arab polytheism practiced in Nabataea, an ancient Arab nation that was well established by the third century BCE and lasted until the Roman annexation in 106 CE.[1] The Nabateans were polytheistic, worshiping a wide variety of local gods, as well as deities such as Baalshamin, Isis, and Greco-Roman gods, including Tyche and Dionysus.[1] They conducted their worship at temples, high places, and betyls. Their religious practices were mostly aniconic, favoring geometric designs to adorn sacred spaces. Much knowledge of Nabataean grave goods has been lost due to extensive looting throughout history. The Nabataeans performed sacrifices, conducted various rituals, and held a belief in an afterlife.

Gods and goddesses

[edit]Most of the deities in the Nabataean religion belonged to the pre-Islamic Arab pantheon, with the inclusion of foreign deities such as Isis and Atargatis.

Dushara, a Nabataean deity whose name means "Lord of the Mountain," was widely worshipped in Petra. He was venerated as the supreme god by the Nabataeans and was often referred to as "Dushara and all the gods."[2] Dushara was regarded as the protector of the Nabataean royal house. However, following the fall of the royal house to the Romans, the religion declined, and its primary deity lost prominence. During this period, Dushara became associated with other gods, including Dionysus, Zeus, and Helios.

Manāt, known as the goddess of fate, was worshipped by those seeking rain and victory over their enemies.

Al-Lāt, referred to as "the great goddess who is in Iram," was widely known in Northern Arabia and Syria. She was associated with the goddess Athena in the Hawran. Al-Lāt was venerated in Palmyra, but her temple shows no evidence of blood rituals being performed there. It is believed that she and Al-Uzza were once a single deity, which bifurcated in the pre-Islamic Meccan tradition.[2] Pre-Islamic Arabs believed that the goddess Al-Lāt, along with Al-‘Uzzá and Manāt, was the daughter of Allah, although Nabataean inscriptions describe her as Allah's wife instead.[3][4][5][6][7] These same inscriptions also refer to both Al-Lāt and Al-‘Uzzá as the "bride of Dushara."[8]

In Arabic, Al-'Uzza's name is believed to mean "the mightiest one." She was venerated in the city of Petra, with her cult primarily centered in the Quraysh and the Hurad Valley, north of Mecca. The goddess was associated with a type of betyl characterized by star-like eyes and was linked to the Greco-Roman goddess Aphrodite.[2] Pre-Islamic Arabs regarded her as one of the daughters of Allah, alongside Al-Lāt and Manāt.[3][4][5][6]

Al-Kutbay was one of the lesser-known deities of the Nabataeans, believed to have had a temple in Gaia and to have been venerated in Iram. There is some ambiguity regarding the deity's gender. In Gaia, Al-Kutbay was considered female, while in Qusrawet, Egypt, the deity was believed to be masculine and referred to as Kutba. However, most evidence suggests that Al-Kutbay was female, as betyls associated with her are similar in design to those of Al-‘Uzzā.[2]

Baalshamin was a Syrian deity who became a Nabataean god following the expansion of Nabataea into southern Syria.[9] His name, meaning "Lord of Heaven," associates him with the sky. Baalshamin is believed to have originated from the storm god Hadad, who was worshipped in Syria and Mesopotamia. As a sky deity, he is often identified with the Greek god Zeus. A temple dedicated to Baalshamin is located at Si, which appears to have been a center for pilgrimage.[2]

Qos, an ancient Edomite deity, was worshipped at Tannur. He was associated with Apollo and lightning.[2]

Hubal was worshipped in the Ka'bah at Mecca. His followers were said to have sought his guidance on matters of lineage, marriage, and death. In his honor, a sacrifice was offered, followed by the casting of seven divination arrows. The answer to their query was determined by the carved words inscribed on the sides of the arrows.[2]

Manotu was a goddess mentioned in tomb inscriptions at Hegra. Her name appeared alongside that of Dushara, serving as a warning of their curse. She is believed to be the same as the goddess Manāt of the Ka'bah in Mecca, who was considered one of the daughters of Allah.[2]

Isis was a foreign deity to the Nabataeans, originating from Egypt and sometimes symbolized by a throne. Depictions of the goddess can be seen at Petra’s Khazneh and the Temple of the Winged Lions.[2]

Atargatis was a foreign deity whose original cult center was at Hierapolis. She was also venerated at Khirbet et-Tannur. Atargatis was alternately referred to as the goddess of grain and fish.[9] She is sometimes depicted seated between two lions and is also associated with a betyl featuring star-like eyes.[2]

Shay’-al-Qawn was regarded as the protector of caravans, soldiers, and other travelers. It is said that his followers disapproved of the consumption of wine.[2]

Obodas is believed to have been a deified Nabataean king, though it remains unclear whether he was Obodas I, II, or III. His association with the royal family suggests that he was venerated through a private cult.[2]

Tyche, a Nabataean goddess, is often depicted alongside the zodiac signs found at Khirbet-et-Tannur. She is typically shown with wings, a mural crown, and holding horns of plenty.[10]

External influences on gods/goddesses

[edit]The majority of Nabataean gods were foreign and were adopted from other cultures. Many Nabataean deities became associated with Greco-Roman gods and goddesses, particularly during the period when Nabataea was under Roman influence. For instance, the Egyptian goddess Isis appeared not only in Nabataean religion but also in Greek and Roman traditions. The god Dushara is often mentioned as a version of Dionysius.[2] The gods Helios and Eros are also found in Nabataean temples. Following the annexation of Nabataea by the Romans, some tombs referred to Greco-Roman gods rather than Nabataean deities, marking a shift in religious practices. For example, in the temple of Qasr, Aphrodite (identified with al-‘Uzza) and Dushara were worshipped.[2]

Relationships between the gods

[edit]The relationships between Nabataean gods are not always clear due to the lack of evidence supporting various claims. In some regions of the kingdom, gods and goddesses are paired as husband and wife, while in other areas, they may not be. For example, the god Dushara is sometimes said to be the husband of Al-Lat, while in other instances, he is described as her son. Similarly, Al-Lat, Al-‘Uzza, and Manāt are often referred to as the daughters of the high god Allah. In some regions of the Nabataean kingdom, both Al-Lat and Al-‘Uzza are considered to be the same goddess.[2]

Rituals and animals

[edit]It is likely that in the city of Petra, there were processional ways connecting temples, such as the Qasr el-Bint temple, the Temple of the Winged Lions, and the Great Temple. The main street running through the city would have facilitated such processions. Other processional routes may have been linked to the so-called high places, such as el-Madh-bah, passing landmarks like the "Roman Soldier" tomb, the "Garden Temple," the Lion Monument, and a rock-cut altar before reaching the high place.[2] The Nabataeans would visit the tombs of relatives for ritual feasting, filling the space with incense and perfumed oils. It is also likely that goods were left inside the tombs as a way of remembering the deceased. Remains of unusual species, such as raptors, goats, rams, and dogs, were used in some rituals.[11] Sacrificing camels to the ancient gods, especially to Dushara, was also not uncommon.[2]

Sacred objects or animals

[edit]- Niches – These are described as miniature temples or adyton of a temple, containing stone pillars or betyls carved out of rock.[2]

- Altars – At times, the Nabataeans used altars as representations of the gods.[2]

- Sacred animals – Eagles, serpents, sphinxes, griffins, and other mythological figures decorate the tombs of the ancient Nabataeans.[2]

- Iconoclasm – There is little evidence of Nabataean iconoclasm. Most deities were portrayed as betyls, sometimes carved in relief, and other times carried during processions. When gods were depicted in human form, they were often represented as "eye-idol" betyls. Due to Greco-Roman influence, statues of Nabataean gods exist. For instance, the goddess Isis is shown in human form, possibly because she was venerated in regions like Egypt and Rome. The god Dushara is depicted in both betyl and statue form throughout the Nabataean kingdom.[2]

Places of worship

[edit]

The Nabataeans had numerous places for religious practice and cult worship, known as "high places." These shrines, temples, and altars were typically open-air structures situated atop nearby mountains.[2] These locations throughout the Nabataean kingdom were dedicated to the worship of the same gods, although the methods of worship varied from site to site. Offerings ranged from material goods and food to live animal sacrifices, and possibly even human sacrifices. The Nabataean kingdom can be divided into five religious regions, each containing sites of religious significance: the Negev and Hejaz, the Hauran, Central Jordan, Southern Jordan, and Northwestern Saudi Arabia.[12] The religious sites in these regions are in varying states of preservation, making it difficult to determine which deities were worshipped at specific shrines, altars, and temples. As a result, the specifics of the cult practices are unclear, and only educated speculations can be made.[13][14]

Sobata

[edit]Located about 40 km southwest of Beersheba, is the city of Sobata was one of the major cities within the Nabataean kingdom. Very few archaeological remains of any form of Nabataean cult worship, including temples, shrines, or altars, have been found. However, a small amount of evidence has been discovered indicating the worship of Dushara.[12][15]

Avdat

[edit]Located in the mountains southeast of Sobata, religious practice in this area primarily focused on the deified Obodas I, who gained fame for reclaiming lands in the Negev from Alexander Jannaeus, leading to the formation of a "King’s cult." At least two documented Nabataean temple complexes exist atop the acropolis, with the smaller of the two dedicated to the deified Obodas III.[12]

Rawwafah

[edit]Located 300 km from Petra, a single temple in the Nabataean style has been discovered. The inscription on the lintel dates the temple to after the fall of the Nabataean kingdom.[13]

Mampsis

[edit]Mampsis is a Nabataean site located about 81 km from Petra. It was an important stop on the incense trade route. Nabataean-style buildings, caravanserais, and water systems have been discovered at the site.[13]

Bostra

[edit]Located in southern Syria, Bostra was the northern capital of the Nabataean kingdom. Evidence of temples can be found at major intersections throughout the city. At the city center, there is a temple complex dedicated to Dushara-A'ra.[12] A'ra is thought to be the god of the Nabataean kings and of the city of Bostra itself. Modern buildings make it difficult to find archaeological evidence of Nabataean cult worship. An inscription reading, "This is the wall which ... and windows which Taymu bar ... built for... Dushara and the rest of the gods of Bostra," is located on what is believed to be this temple.

Seeia

[edit]Located north of Bostra, near Canatha, the settlement contains three large temples. The largest temple is dedicated to Baalshamin, while the two smaller temples are dedicated to unknown deities. One of these smaller temples contains an inscription to the local goddess Seeia and may have been used to worship her. The temple complex is not of Nabataean design but is an amalgamation of architectural styles from cultures along the northern Nabataean border.

Sahr

[edit]The temples are similar in style to those located in Wadi Rum, Dharih, Tannur, and Qasrawet.[13]

Sur

[edit]The temples are similar in style to those found in Wadi Rum, Dharih, Tannur, and Qasrawet.[13]

Suweida

[edit]The temples are similar to those located near Petra in Wadi Rum, Dharih, Tannur, and Qasrawet. Nabataean inscriptions indicate cults dedicated to Al-Lat and Baalshamin.[13]

Khirbet Tannur

[edit]Located in Central Jordan, the temple, or high place, is situated alone atop the summit of Jebel Tannur. It is accessible only via a single, steep staircase pathway. The site's seclusion may indicate that it held high religious importance for the Nabataeans.[12] The doorway to the inner sanctuary of the temple is decorated with representations of vegetation, foliage, and fruits. Glueck identifies these as symbols of the Syrian goddess Atargatis. The inner sanctuary is adorned with images of fruit, fish, vegetation, thunderbolts, and representations of deities. Glueck attributes these iconographies to the Mesopotamian storm god Hadad, though Tyche and Nike are also represented. Starckly notes that the only named god is the Edomite weather god Qos, with an inscription on a stele at the site naming him as the god of Hurawa.[2][12]

Khirbet edh-Dharih

[edit]Located 7 km south of Hurawa, the temple at Khirbet edh-Dharih is remarkably well-preserved. The temple complex is surrounded by an outer and inner courtyard, with a paved pathway leading to the porticoes. There are also benches arranged in the form of a theatron. The temple itself is divided into three sections, with a large open vestibule. From here, one enters the cella, which was painted in rich, vibrant colors. At the back of the cella was the motab and betyl, a square podium flanked by stairs, which served as the seat of the divine. Despite its excellent condition, it is not known which god was worshipped here.[12]

Petra

[edit]The capital of the Nabataean Kingdom around 312 BC, Petra is famous for its remarkable rock-cut architecture. Located within the Shara Mountains, Petra was home to Dushara, the primary male god, accompanied by the female trinity: Al-'Uzzá, Al-Lat, and Manāt.[2][14] A stele dedicated to the Edomite god Qos is located within the city. The Nabataeans worshipped pre-Islamic Arab gods and goddesses, along with deified kings such as Obodas I. Temple layout and design show influences from Roman, Greek, Egyptian, and Persian temple architecture, with the temples of Qasr al-Bint and the Temple of the Winged Lion serving as examples.[14] The podium within the Temple of the Winged Lion housed the altar, where sacrifices would have been made or the betyl of the worshiped deity.[15] Based on the idols and imagery found within the Temple of the Winged Lion, it is theorized to be dedicated to Dushara.[15] The High Place is located atop the mountains surrounding Petra. Used for offering gifts and sacrificing animals, and possibly humans, to the gods, the High Place consists of a pool for collecting water, two altars, and a large open courtyard.[14]

The temple features a 20-meter-long processional way leading to a courtyard with a view of Jebel Qalkha. The design of the betyls, along with the remains of offering points, suggests the possible worship of Dushara, and possibly even Jupiter.

The temple is dedicated to Al-Lat. A rock sanctuary to Ayn esh-Shallaleh is located behind the temple to Al-Lat. Betyls and cult niches dedicated to Dushara and Baalshamin are also present.

Northwestern Saudi Arabia

[edit]

A cult ritual circle on top of Jebel Ithlib rests on a rocky outcropping. Small betyls and cult niches dedicated to other gods appear around the Jebel Ithlib site. An inscription reading "Lord of the Temple" may refer to Dushara. Marseha cults were located here. Today, Hegra is known as Mada’in Saleh.[2][12]

Outside the Middle East

[edit]In 2023, an underwater archaeological survey of the port of Puteoli (modern Pozzuoli, Italy) uncovered a submerged Nabataean temple. This is the first and only known Nabataean temple outside the Nabataean homeland. The temple appears to have been constructed using local Roman-style materials and techniques, and includes inscriptions in Latin, suggesting a level of integration between Nabataean merchants and the Roman community. Inscriptions found at the site, such as "Dusari sacrum," indicate that the temple served as a place of worship dedicated to Dushara. The temple is believed to have reached its end when it was filled with concrete following the establishment of the Roman province of Arabia Petraea in AD 106, marking the decline of Nabataean trade.[16]

Processional ways

[edit]The processional way leading to places of worship varied from site to site. Some locations were simple rock paths, lacking decoration along the way, while others, like Petra, featured carvings, monuments, sculptures, betyls, and occasionally obelisks. Petra's processional way includes the Lion Fountain, a lion relief, the Garden Tomb, and the Nabataean Quarry.

Temple layout

[edit]Nabataean temples vary greatly in design, with no single standard layout. The Nabataeans adopted and adapted elements of temple design from the cultures with which they traded. Greek, Roman, Persian, Egyptian, and Syrian influences can be seen to varying degrees in these temples.

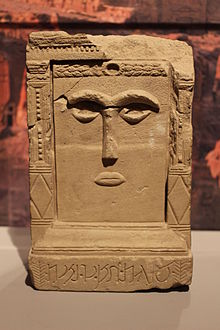

Betyls

[edit]

Betyls are blocks of stone that represent the gods of the Nabataeans. The term "betyl" is derived from the Greek word Βαιτύλια and a myth told by the Greeks about Ouranos, who created animated stones that fell from heaven.[17] Betyls were commonly placed on altars or platforms where religious rituals were performed.[17] Occasionally, betyls have been found in tombs.[18] Dr. Gustaf Dalman was the first to classify the various types of betyls. According to Dr. Dalman, the different types of betyls are:

- Plain betyls

- Rectangular slab (Pfeiler, block, stela)

- High rectangular slab with a rounded top

- Semicircular or hemispherical slab

- Dome-shaped spherical betyl (squat omphalos, ovoid)

- Eye betyls

- Face stelae

Eye betyls and face stelae are of particular interest to scholars due to the inconsistency with what is generally understood as Nabataean aniconism. There is ongoing debate over whether the betyls were viewed as containers for gods or as representations of the gods themselves.[19] Grooves in the floors of niches and holes in the tops of altars have led to the conclusion that betyls may have been stored for safekeeping and then transported to the worship site.[17]

Rituals

[edit]Offerings

[edit]Offerings of libations (most likely wine) and incense played an important role in Nabataean communal worship. There are speculations that the Nabataeans also offered oils or other goods, but the only definite offerings are libations and incense. Strabo confirms that libations and frankincense were offered daily to the sun (Dushara).[20] There is also evidence of silver and gold offerings to gods, though the text in which this is found is unclear as to whether these could be considered tithes.[20]

Sacrifices

[edit]Animal sacrifices were common in Nabataean rituals. While Porphyry’s De Abstenentia reports that a boy was sacrificed annually and buried underneath an altar in Dumat Al-Jandal, there is no direct evidence linking the Nabataeans to human sacrifice.[21]

Specific dates

[edit]There are few primary sources regarding the religious festivals celebrated by the Nabataeans. However, the presence of two inscriptions to Dushara-A’ra, dated to the month of Nisan, may indicate the celebration of a spring festival.[20]

Funerary rituals

[edit]Meaning of tomb architecture

[edit]The rock-cut tombs of the Nabataeans were designed to be functional, serving as comfortable resting places for the dead.[20] Like the Egyptians, they believed that the deceased continued to live and needed food and care after death. As a result, those who could afford it often included gardens and dining areas around their tombs for feasting.[20] Eagles, the symbol of Dushara, were sometimes carved above doorways for protection.[20]

Curses

[edit]Many Nabataean tombs featured inscriptions that identified the intended occupant and reflected the social status and piety of the tomb owner. Inscriptions became widespread across Nabataea, listing actions (e.g., selling or mortgaging the tomb) that were prohibited, along with details of fines and punishments for those who ignored the curses engraved on the tomb's surface. These curses were often formulaic, such as: “And the curse of [name of god] on anyone who reads this inscription and does not say [blessing or other phrase].” Inscriptions found at Mada'in Saleh and other large Nabataean cities name the tomb owners, outline curses, and specify who should be buried in the tomb. However, with the exceptions of the Tomb of Sextius Florentinus, the Turkmaniyah Tomb, and a few others, Petran tombs generally lacked inscriptions.[22]

Concepts of the afterlife

[edit]Little is known about how the Nabataeans viewed the afterlife, but assumptions have been made based on the material goods they left behind. Tombs and grave goods provide valuable insights into the lives of ancient cultures, and the layout of tombs in Petra, Bosra, Mada'in Saleh and other prominent cities is significant for understanding their beliefs. Known grave goods include an alabaster jug found at Mamphis and various vessels from funerary feasts.[23] The emphasis placed on familial burial niches, dining halls, and grave goods suggests that the Nabataeans believed the afterlife was a place where one could enjoy food and company with friends and family.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Patrich, Joseph. The Formation of Nabataean Art: Prohibition of a Graven Image Among the Nabateans. Jerusalem: Magnes, 1990. Print.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Healey, John F. The Religion of the Nabataeans: A Conspectus. Leiden: EJ. Brill, 2001.

- ^ a b Jonathan Porter Berkey (2003). The Formation of Islam: Religion and Society in the Near East, 600-1800. Cambridge University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-521-58813-3.

- ^ a b Neal Robinson (5 November 2013). Islam: A Concise Introduction. Routledge. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-136-81773-1.

- ^ a b Francis E. Peters (1994). Muhammad and the Origins of Islam. SUNY Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-7914-1875-8.

- ^ a b Daniel C. Peterson (26 February 2007). Muhammad, Prophet of God. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-8028-0754-0.

- ^ Aaron W. Hughes (9 April 2013). The Idea of Idolatry and the Emergence of Islam: From Polemic to History. Columbia University Press. p. 25. ISBN 9780231531924.

- ^ Paola Corrente (26 June 2013). Alberto Bernabé; Miguel Herrero de Jáuregui; Ana Isabel Jiménez San Cristóbal; Raquel Martín Hernández (eds.). Redefining Dionysos. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 263, 264. ISBN 9783110301328.

- ^ a b Alpass, Peter. Religions in the Graeco-Roman World, Leiden, NLD:Brill, 2013

- ^ Glueck, Nelson. The Zodiac of Khirbet et-Tannûr. Boston, MA : American Schools of Oriental Research,1952

- ^ Rawashdeh, Saeb. Ancient Nabataean rituals uncovered and explored at IFPO workshop. Jordan Times:23 Sept. 2015

- ^ a b c d e f g h Peterson, Stephanie. "The Cult of Dushara and the Roman Annexation of Nabataea." Ma Thesis, McMaster, August, 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f Anderson,Bjo. Constructing Nabataea: Identity, Ideology, and Connectivity. Classical Art & Archaeology, The University of Michigan, 2005 Committee: M.C. Root (co-chair), T. Gagos (co-chair), S. Alcock, S. Herbert, N. Yoffee.

- ^ a b c d Wenning, R. 1987. Die Nabatäer-Denkmäler und Geschichte:Eine Bestandesaufnahme des archäologischen Befundes, Freiburg: Universitätsverlag Freiburg Schweiz.

- ^ a b c Tholbecq L. (2007) “Nabataean Monumental Architecture.” In: Politis KD (ed) The World of the Herods and the Nabataeans: An International Conference at the British Museum, 17–19 April 2001, 1033-144. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag.

- ^ Stefanile, Michele; Silani, Michele; Tardugno, Maria Luisa (2024). "The submerged Nabataean temple in Puteoli at Pozzuoli, Italy: first campaign of underwater research". Antiquity. 98 (400): e20. doi:10.15184/aqy.2024.107. ISSN 0003-598X.

- ^ a b c Wenning, Robert. “The Betyls of Petra”. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 324 (2001): 79–95.

- ^ Wenning, Robert. “Decoding Nabataean Betyls.” Proceedings of the 4th International Congress of the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, 29 March – 3 April 2004 1 (2008): 613–619. Print.

- ^ Healey, John F. “Images and Rituals.” The Religion of the Nabataeans: A Conspectus. Boston: Brill, 2001. 154–157. Print.

- ^ a b c d e f Healey, John F. “Images and Rituals.” The Religion of the Nabataeans: A Conspectus. Boston: Brill, 2001. 169–175. Print.

- ^ Healey, John F. (2001). The religion of the Nabataeans: a conspectus. Religions in the Graeco-Roman world. Leiden: Brill. p. 162. ISBN 978-90-04-10754-0.

- ^ Wadeson, Lucy. “Nabataean Tomb Complexes At Petra: New Insights in the Light of Recent Fieldwork.” (2011): n. pag. Web. 11–25 2015. <http://www.ascs.org.au/news/ascs32/Wadeson.pdf>.

- ^ Perry, Megan A. "Life and Death in Nabataea: The North Ridge Tombs and Nabataean Burial Practices." Near Eastern Archaeology65.4 (2002): 265-270. ATLA Religion Database with ATLASerials. Web. 16 Nov. 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Moutsopoulos, N. “Observations sur les representations du Panthéon Nabatéen”. In: Balkan studies 33 (1992): 5-50.