Monoamine oxidase inhibitor

| Monoamine oxidase inhibitor | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

| |

| Class identifiers | |

| Synonyms | MAOI, RIMA |

| Use | Treatment of major depressive disorder, atypical depression, Parkinson's disease, and several other disorders |

| ATC code | N06AF |

| Mechanism of action | Enzyme inhibitor |

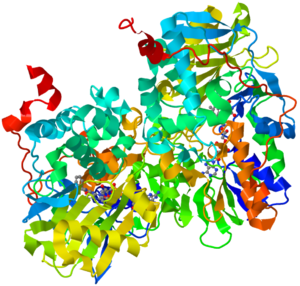

| Biological target | Monoamine oxidase enzymes: MAO-A and/or MAO-B |

| External links | |

| MeSH | D008996 |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are a class of drugs that inhibit the activity of one or both monoamine oxidase enzymes: monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A) and monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B). They are best known as effective antidepressants, especially for treatment-resistant depression and atypical depression.[1] They are also used to treat panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, Parkinson's disease, and several other disorders.

Reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase A (RIMAs) are a subclass of MAOIs that selectively and reversibly inhibit the MAO-A enzyme. RIMAs are used clinically in the treatment of depression and dysthymia. Due to their reversibility, they are safer in single-drug overdose than the older, irreversible MAOIs,[2] and weaker in increasing the monoamines important in depressive disorder.[3] RIMAs have not gained widespread market share in the United States.

Medical uses

[edit]

MAOIs have been found to be effective in the treatment of panic disorder with agoraphobia,[4] social phobia,[5][6][7] atypical depression[8][9] or mixed anxiety disorder and depression, bulimia,[10][11][12][13] and post-traumatic stress disorder,[14] as well as borderline personality disorder,[15] and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD).[16][17] MAOIs appear to be particularly effective in the management of bipolar depression according to a retrospective-analysis from 2009.[18] There are reports of MAOI efficacy in OCD, trichotillomania, body dysmorphic disorder, and avoidant personality disorder, but these reports are from uncontrolled case reports.[19]

MAOIs can also be used in the treatment of Parkinson's disease by targeting MAO-B in particular (therefore affecting dopaminergic neurons), as well as providing an alternative for migraine prophylaxis. Inhibition of both MAO-A and MAO-B is used in the treatment of clinical depression and anxiety.

MAOIs appear to be particularly indicated for outpatients with dysthymia complicated by panic disorder or hysteroid dysphoria.[20]

Newer MAOIs such as selegiline (typically used in the treatment of Parkinson's disease) and the reversible MAOI moclobemide provide a safer alternative[19] and are now sometimes used as first-line therapy.

Pargyline is a non-selective MAOI that was previously used as an antihypertensive agent to treat hypertension (high blood pressure).[21][22]

Side effects

[edit]Hypertensive crisis

[edit]People taking MAOIs generally need to change their diets to limit or avoid foods and beverages containing tyramine.[23] If large amounts of tyramine are consumed, they may develop a hypertensive crisis, which can be fatal.[24] Examples of foods and beverages with potentially high levels of tyramine include cheese, Chianti wine, and pickled fish.[25] Excessive concentrations of tyramine in blood plasma can lead to hypertensive crisis by increasing the release of norepinephrine (NE), which causes blood vessels to constrict by activating alpha-1 adrenergic receptors.[26] Ordinarily, MAO-A would destroy the excess NE; when MAO-A is inhibited, however, NE levels get too high, leading to dangerous increases in blood pressure.

RIMAs are displaced from MAO-A in the presence of tyramine,[27] rather than inhibiting its breakdown in the liver as general MAOIs do. Additionally, MAO-B remains free and continues to metabolize tyramine in the stomach, although this is less significant than the liver action. Thus, RIMAs are unlikely to elicit tyramine-mediated hypertensive crisis; moreover, dietary modifications are not usually necessary when taking a reversible inhibitor of MAO-A (i.e., moclobemide) or low doses of selective MAO-B inhibitors (e.g., selegiline 6 mg/24 hours transdermal patch).[26][28][29]

Drug interactions

[edit]The most significant risk associated with the use of MAOIs is the potential for drug interactions with over-the-counter, prescription, or illegally obtained medications, and some dietary supplements (e.g., St. John's wort or tryptophan). It is vital that a doctor supervise such combinations to avoid adverse reactions. For this reason, many users carry an MAOI-card, which lets emergency medical personnel know what drugs to avoid (e.g. adrenaline [epinephrine] dosage should be reduced by 75%, and duration is extended).[25]

Tryptophan supplements can be consumed with MAOIs, but can result in transient serotonin syndrome.[30]

MAOIs should not be combined with other psychoactive substances (antidepressants, painkillers, stimulants, including prescribed, OTC and illegally acquired drugs, etc.) except under expert care. Certain combinations can cause lethal reactions; common examples include SSRIs, tricyclics, MDMA, meperidine,[31] tramadol, and dextromethorphan,[32] whereas combinations with LSD, psilocybin, or DMT appear to be relatively safe.[33][citation needed] Drugs that affect the release or reuptake of epinephrine, norepinephrine, serotonin or dopamine typically need to be administered at lower doses due to the resulting potentiated and prolonged effect. MAOIs also interact with tobacco-containing products (e.g. cigarettes) and may potentiate the effects of certain compounds in tobacco.[34][35][36] This may be reflected in the difficulty of smoking cessation, as tobacco contains naturally occurring MAOI compounds in addition to the nicotine.[34][35][36]

While safer than general MAOIs, RIMAs still possess significant and potentially serious drug interactions with many common drugs; in particular, they can cause serotonin syndrome or hypertensive crisis when combined with almost any antidepressant or stimulant, common migraine medications, certain herbs, or most cold medicines (including decongestants, antihistamines, and cough syrup).[citation needed]

Ocular alpha-2 agonists such as brimonidine and apraclonidine are glaucoma medications which reduce intraocular pressure by decreasing aqueous production. These alpha-2 agonists should not be given with oral MAOIs due to the risk of hypertensive crisis.[37]

Withdrawal

[edit]Antidepressants including MAOIs have some dependence-producing effects, the most notable one being a discontinuation syndrome, which may be severe especially if MAOIs are discontinued abruptly or too rapidly. The dependence-producing potential of MAOIs or antidepressants in general is not as significant as benzodiazepines. Discontinuation symptoms can be managed by tapering, a gradual reduction in dosage over a period of days, weeks or sometimes months to minimize or prevent withdrawal symptoms.[38]

MAOIs, as with most antidepressant medication, may not alter the course of the disorder in a significant, permanent way, so it is possible that discontinuation can return the patient to the pre-treatment state.[39] This consideration complicates prescribing between an MAOI and an SSRI, because it is necessary to clear the system completely of one drug before starting another. One physician organization recommends the dose to be tapered down over a minimum of four weeks, followed by a two-week washout period.[40] The result is that a depressed patient will have to bear the depression without chemical help during the drug-free interval. This may be preferable to risking the effects of an interaction between the two drugs.[40]

Mechanism of action

[edit]

MAOIs act by inhibiting the activity of monoamine oxidase, thus preventing the breakdown of monoamine neurotransmitters and thereby increasing their availability. There are two isoforms of monoamine oxidase, MAO-A and MAO-B. MAO-A preferentially deaminates serotonin, melatonin, epinephrine, and norepinephrine. MAO-B preferentially deaminates phenethylamine and certain other trace amines; in contrast, MAO-A preferentially deaminates other trace amines, like tyramine, whereas dopamine is equally deaminated by both types.

Reversibility

[edit]The early MAOIs covalently bound to the monoamine oxidase enzymes, thus inhibiting them irreversibly; the bound enzyme could not function and thus enzyme activity was blocked until the cell made new enzymes. The enzymes turn over approximately every two weeks. A few newer MAOIs, a notable one being moclobemide, are reversible, meaning that they are able to detach from the enzyme to facilitate usual catabolism of the substrate. The level of inhibition in this way is governed by the concentrations of the substrate and the MAOI.[41]

Harmaline found in Peganum harmala, Banisteriopsis caapi, and Passiflora incarnata is a reversible inhibitor of monoamine oxidase A (RIMA).[42]

Selectivity

[edit]In addition to reversibility, MAOIs differ by their selectivity of the MAO enzyme subtype. Some MAOIs inhibit both MAO-A and MAO-B equally, other MAOIs have been developed to target one over the other.

MAO-A inhibition reduces the breakdown of primarily serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine; selective inhibition of MAO-A allows for tyramine to be metabolised via MAO-B.[43] Agents that act on serotonin, if taken with another serotonin-enhancing agent, may result in a potentially fatal interaction called serotonin syndrome; if taken with irreversible and unselective inhibitors (such as older MAOIs) a hypertensive crisis may result due to tyramine food interactions. Tyramine is broken down by MAO-A and MAO-B, therefore inhibiting this action may result in its excessive build-up, so diet must be monitored for tyramine intake.

MAO-B inhibition reduces the breakdown mainly of dopamine and phenethylamine, so there are no associated dietary restrictions. MAO-B would also metabolize tyramine, as the only differences between dopamine, phenethylamine, and tyramine are two phenylhydroxyl groups on carbons 3 and 4. The 4-OH would not be a steric hindrance to MAO-B on tyramine.[44] Selegiline is selective for MAO-B at low doses, but non-selective at higher doses.

History

[edit]The knowledge of MAOIs began with the serendipitous discovery that iproniazid was a potent MAO inhibitor (MAOI).[45] Originally intended for the treatment of tuberculosis, in 1952, iproniazid's antidepressant properties were discovered when researchers noted that the depressed patients given iproniazid experienced a relief of their depression. Subsequent in vitro work led to the discovery that it inhibited MAO and eventually to the monoamine theory of depression. MAOIs became widely used as antidepressants in the early 1950s. The discovery of the 2 isoenzymes of MAO has led to the development of selective MAOIs that may have a more favorable side-effect profile.[46]

The older MAOIs' heyday was mostly between the years 1957 and 1970.[43] The initial popularity of the 'classic' non-selective irreversible MAO inhibitors began to wane due to their serious interactions with sympathomimetic drugs and tyramine-containing foods that could lead to dangerous hypertensive emergencies. As a result, the use by medical practitioners of these older MAOIs declined. When scientists discovered that there are two different MAO enzymes (MAO-A and MAO-B), they developed selective compounds for MAO-B, (for example, selegiline, which is used for Parkinson's disease), to reduce the side-effects and serious interactions. Further improvement occurred with the development of compounds (moclobemide and toloxatone) that not only are selective but cause reversible MAO-A inhibition and a reduction in dietary and drug interactions.[47][48] Moclobemide, was the first reversible inhibitor of MAO-A to enter widespread clinical practice.[49]

A transdermal patch form of the MAOI selegiline, called Emsam, was approved for use in depression by the Food and Drug Administration in the United States on 28 February 2006.[50]

List of MAO inhibiting drugs

[edit]Marketed MAOIs

[edit]- Nonselective MAO-A/MAO-B inhibitors

- Hydrazine (antidepressant)

- Isocarboxazid (Marplan)

- Hydracarbazine

- Phenelzine (Nardil, Nardelzine)

- Non-hydrazines

- Tranylcypromine (Parnate, Jatrosom)

- Hydrazine (antidepressant)

- Selective MAO-A inhibitors

- Bifemelane (Alnert, Celeport) (available in Japan)

- Methylene blue (Urelene blue, Provayblue, Proveblue)

- Moclobemide (Aurorix, Manerix, Moclamine)

- Pirlindole (Pirazidol) (available in Russia)

- Selective MAO-B inhibitors

- Rasagiline (Azilect)

- Selegiline (Deprenyl, Eldepryl, Emsam, Zelapar)

- Safinamide (Xadago)

Linezolid is an antibiotic drug with weak, reversible MAO-inhibiting activity.[51]

The antibiotic furazolidone also has MAO-inhibiting activity [52]

Methylene blue (methylthioninium chloride), the antidote indicated for drug-induced methemoglobinemia on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, among a plethora of other off-label uses, is a highly potent, reversible MAO inhibitor.[53]

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved these MAOIs to treat depression:[54]

- Isocarboxazid (Marplan)

- Phenelzine (Nardil)

- Selegiline (Emsam)

- Tranylcypromine (Parnate)

MAOIs that have been withdrawn from the market

[edit]- Nonselective MAO-A/MAO-B inhibitors

- Hydrazines

- Benmoxin (Nerusil, Neuralex)

- Iproclozide (Sursum)

- Iproniazid (Marsilid, Iprozid, Ipronid, Rivivol, Propilniazida)

- Mebanazine (Actomol)

- Nialamide (Niamid)

- Octamoxin (Ximaol, Nimaol)

- Pheniprazine (Catron)

- Phenoxypropazine (Drazine)

- Pivalylbenzhydrazine (Tersavid)

- Safrazine (Safra) (discontinued worldwide except for Japan)

- Non-hydrazines

- Caroxazone (Surodil, Timostenil)

- Hydrazines

- Selective MAO-A inhibitors

- Minaprine (Cantor)

- Toloxatone (Humoryl)

List of RIMAs

[edit]Marketed pharmaceuticals

- Moclobemide (Aurorix, Manerix, Moclamine)

Other pharmaceuticals

- Brofaromine (Consonar)

- Caroxazone (Surodil, Timostenil)

- Eprobemide (Befol)[55]

- Methylene blue

- Metralindole (Inkazan)

- Minaprine (Cantor)

- Pirlindole (Pirazidol)

Naturally occurring RIMAs in plants

Only reversible phytochemical MAOIs have been characterized.[56]

Research compounds

- Amiflamine (FLA-336)

- Befloxatone (MD-370,503)

- Cimoxatone (MD-780,515)

- Esuprone

- Sercloremine (CGP-4718-A)

- Tetrindole

- CX157 (TriRima)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Cristancho, Mario A. (20 November 2012). "Atypical Depression in the 21st Century: Diagnostic and Treatment Issues". Psychiatric Times. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ^ Isbister GK, et al. (2003). "Moclobemide poisoning: toxicokinetics and occurrence of serotonin toxicity". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 56 (4): 441–450. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01895.x. PMC 1884375. PMID 12968990.

- ^ "Neuroscience Education Institute > Activities > 2012CurbConsultPosted". www.neiglobal.com.

- ^ Buigues J, Vallejo J (February 1987). "Therapeutic response to phenelzine in patients with panic disorder and agoraphobia with panic attacks". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 48 (2): 55–9. PMID 3542985.

- ^ Liebowitz MR, Schneier F, Campeas R, Hollander E, Hatterer J, Fyer A, Gorman J, Papp L, Davies S, Gully R (April 1992). "Phenelzine vs atenolol in social phobia. A placebo-controlled comparison". Archives of General Psychiatry. 49 (4): 290–300. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.49.4.290. PMID 1558463.

- ^ Versiani M, Nardi AE, Mundim FD, Alves AB, Liebowitz MR, Amrein R (September 1992). "Pharmacotherapy of social phobia. A controlled study with moclobemide and phenelzine". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 161 (3): 353–60. doi:10.1192/bjp.161.3.353. PMID 1393304. S2CID 45341667.

- ^ Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hope DA, Schneier FR, Holt CS, Welkowitz LA, Juster HR, Campeas R, Bruch MA, Cloitre M, Fallon B, Klein DF (December 1998). "Cognitive behavioral group therapy vs phenelzine therapy for social phobia: 12-week outcome". Archives of General Psychiatry. 55 (12): 1133–41. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.485.5909. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.55.12.1133. PMID 9862558.

- ^ Jarrett RB, Schaffer M, McIntire D, Witt-Browder A, Kraft D, Risser RC (May 1999). "Treatment of atypical depression with cognitive therapy or phenelzine: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Archives of General Psychiatry. 56 (5): 431–7. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.56.5.431. PMC 1475805. PMID 10232298.

- ^ Liebowitz MR, Quitkin FM, Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, Harrison W, Rabkin J, Tricamo E, Markowitz JS, Klein DF (July 1984). "Phenelzine v imipramine in atypical depression. A preliminary report". Archives of General Psychiatry. 41 (7): 669–77. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790180039005. PMID 6375621.

- ^ Walsh BT, Stewart JW, Roose SP, Gladis M, Glassman AH (November 1984). "Treatment of bulimia with phenelzine. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study". Archives of General Psychiatry. 41 (11): 1105–9. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790220095015. PMID 6388524.

- ^ Rothschild R, Quitkin HM, Quitkin FM, Stewart JW, Ocepek-Welikson K, McGrath PJ, Tricamo E (January 1994). "A double-blind placebo-controlled comparison of phenelzine and imipramine in the treatment of bulimia in atypical depressives". The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 15 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199401)15:1<1::AID-EAT2260150102>3.0.CO;2-E. PMID 8124322.

- ^ Walsh BT, Stewart JW, Roose SP, Gladis M, Glassman AH (1985). "A double-blind trial of phenelzine in bulimia". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 19 (2–3): 485–9. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(85)90058-5. PMID 3900362.

- ^ Walsh BT, Gladis M, Roose SP, Stewart JW, Stetner F, Glassman AH (May 1988). "Phenelzine vs placebo in 50 patients with bulimia". Archives of General Psychiatry. 45 (5): 471–5. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800290091011. PMID 3282482.

- ^ Davidson J, Walker JI, Kilts C (February 1987). "A pilot study of phenelzine in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 150 (2): 252–5. doi:10.1192/bjp.150.2.252. PMID 3651684. S2CID 10001735.

- ^ Soloff PH, Cornelius J, George A, Nathan S, Perel JM, Ulrich RF (May 1993). "Efficacy of phenelzine and haloperidol in borderline personality disorder". Archives of General Psychiatry. 50 (5): 377–85. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820170055007. PMID 8489326.

- ^ Vallejo, J.; Olivares, J.; Marcos, T.; Bulbena, A.; Menchón, J. M. (2 January 2018). "Clomipramine versus Phenelzine in Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder". British Journal of Psychiatry. 161 (5): 665–670. doi:10.1192/bjp.161.5.665. PMID 1422616. S2CID 36232956.

- ^ Annesley, P. T. (29 January 2018). "Nardil Response in a Chronic Obsessive Compulsive". British Journal of Psychiatry. 115 (523): 748. doi:10.1192/bjp.115.523.748. PMID 5806868. S2CID 31997372.

- ^ Mallinger AG, Frank E, Thase ME, Barwell MM, Diazgranados N, Luckenbaugh DA, Kupfer DJ (2009). "Revisiting the effectiveness of standard antidepressants in bipolar disorder: are monoamine oxidase inhibitors superior?". Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 42 (2): 64–74. PMC 3570273. PMID 19629023.

- ^ a b Liebowitz MR, Hollander E, Schneier F, Campeas R, Welkowitz L, Hatterer J, Fallon B (1990). "Reversible and irreversible monoamine oxidase inhibitors in other psychiatric disorders". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 360 (S360): 29–34. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb05321.x. PMID 2248064. S2CID 30319319.

- ^ http://www.psycom.net/hysteroid.html Dowson JH (1987). "MAO inhibitors in mental disease: Their current status". Monoamine Oxidase Enzymes. Vol. 23. pp. 121–38. doi:10.1007/978-3-7091-8901-6_8. ISBN 978-3-211-81985-2. PMID 3295114.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Finberg JP (August 2014). "Update on the pharmacology of selective inhibitors of MAO-A and MAO-B: focus on modulation of CNS monoamine neurotransmitter release". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 143 (2): 133–152. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.02.010. PMID 24607445.

- ^ Hayes AH, Schneck DW (May 1976). "Antihypertensive pharmacotherapy". Postgraduate Medicine. 59 (5): 155–162. doi:10.1080/00325481.1976.11714363. PMID 57611.

- ^ Gillman, Peter Kenneth (September 2018). "A reassessment of the safety profile of monoamine oxidase inhibitors: elucidating tired old tyramine myths". Journal of Neural Transmission. 125 (11): 1707–1717. doi:10.1007/s00702-018-1932-y. ISSN 0300-9564. PMID 30255284. S2CID 52823188.

- ^ Grady MM, Stahl SM (March 2012). "Practical guide for prescribing MAOIs: debunking myths and removing barriers". CNS Spectrums. 17 (1): 2–10. doi:10.1017/S109285291200003X. PMID 22790112. S2CID 206312008. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017.

- ^ a b Mosher, Clayton James, and Scott Akins. Drugs and Drug Policy : The Control of Consciousness Alteration. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage, 2007.[page needed]

- ^ a b Stahl S (2011). Case Studies: Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology.

- ^ Lotufo-Neto F, Trivedi M, Thase ME (March 1999). "Meta-analysis of the reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase type A moclobemide and brofaromine for the treatment of depression". Neuropsychopharmacology. 20 (3): 226–47. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00075-X. PMID 10063483.

- ^ FDA. "EMSAM Medication Guide" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2015.

- ^ Lavian G, Finberg JP, Youdim MB (1993). "The advent of a new generation of monoamine oxidase inhibitor antidepressants: pharmacologic studies with moclobemide and brofaromine". Clinical Neuropharmacology. 16 (Suppl 2): S1–7. PMID 8313392.

- ^ Boyer EW, Shannon M (March 2005). "The serotonin syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (11): 1112–20. doi:10.1056/NEJMra041867. PMID 15784664. S2CID 37959124.

- ^ Pharmacology from H.P. Rang, M.M. Dale, J.M. Ritter, P.K. Moore, year 2003, chapter 38

- ^ "MHRA PAR Dextromethorphan hydrobromide, p. 12" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 May 2017.

- ^ Malcolm, B., & Thomas, K (2022). "Serotonin toxicity of serotonergic psychedelics". Psychopharmacology. 239 (6): 1881–1891. doi:10.1007/s00213-021-05876-x. PMID 34251464. S2CID 235796130.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Berlin I, Anthenelli RM (March 2001). "Monoamine oxidases and tobacco smoking". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 4 (1): 33–42. doi:10.1017/S1461145701002188. PMID 11343627.

- ^ a b Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Pappas N, Logan J, Shea C, Alexoff D, MacGregor RR, Schlyer DJ, Zezulkova I, Wolf AP (November 1996). "Brain monoamine oxidase A inhibition in cigarette smokers". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 93 (24): 14065–9. Bibcode:1996PNAS...9314065F. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.24.14065. PMC 19495. PMID 8943061.

- ^ a b Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Pappas N, Logan J, MacGregor R, Alexoff D, Shea C, Schlyer D, Wolf AP, Warner D, Zezulkova I, Cilento R (February 1996). "Inhibition of monoamine oxidase B in the brains of smokers". Nature. 379 (6567): 733–6. Bibcode:1996Natur.379..733F. doi:10.1038/379733a0. PMID 8602220. S2CID 33217880.

- ^ Kanski's Clinical Ophthalmology, 8th Edition (2016). Brad Bowling. ISBN 978-0-7020-5572-0 978-0-7020-5573-7 p. 332

- ^ van Broekhoven F, Kan CC, Zitman FG (June 2002). "Dependence potential of antidepressants compared to benzodiazepines". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 26 (5): 939–43. doi:10.1016/S0278-5846(02)00209-9. PMID 12369270. S2CID 14286356.

- ^ Dobson KS, et al. (June 2008). "Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the prevention of relapse and recurrence in major depression". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 76 (3): 468–77. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.76.3.468. PMC 2648513. PMID 18540740.

- ^ a b "Switching patients from phenelzine to other antidepressants". Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. 11 May 2020. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ Fowler JS, Logan J, Azzaro AJ, Fielding RM, Zhu W, Poshusta AK, Burch D, Brand B, Free J, Asgharnejad M, Wang GJ, Telang F, Hubbard B, Jayne M, King P, Carter P, Carter S, Xu Y, Shea C, Muench L, Alexoff D, Shumay E, Schueller M, Warner D, Apelskog-Torres K (February 2010). "Reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase-A (RIMAs): robust, reversible inhibition of human brain MAO-A by CX157". Neuropsychopharmacology. 35 (3): 623–31. doi:10.1038/npp.2009.167. PMC 2833271. PMID 19890267.

- ^ Edward J. Massaro (2002). Handbook of Neurotoxicology. Humana Press. ISBN 9780896037960.

- ^ a b Nowakowska E, Chodera A (July 1997). "[Inhibitory monoamine oxidases of the new generation]" [New generation of monoaminooxidase inhibitors]. Polski Merkuriusz Lekarski (in Polish). 3 (13): 1–4. PMID 9432289.

- ^ Edmondson DE, Binda C, Mattevi A (August 2007). "Structural insights into the mechanism of amine oxidation by monoamine oxidases A and B". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 464 (2): 269–76. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2007.05.006. PMC 1993809. PMID 17573034.

- ^ Ramachandraih CT, Subramanyam N, Bar KJ, Baker G, Yeragani VK (April 2011). "Antidepressants: From MAOIs to SSRIs and more". Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 53 (2): 180–2. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.82567. PMC 3136031. PMID 21772661.

- ^ Shulman KI, Herrmann N, Walker SE (October 2013). "Current place of monoamine oxidase inhibitors in the treatment of depression". CNS Drugs. 27 (10): 789–97. doi:10.1007/s40263-013-0097-3. PMID 23934742. S2CID 21625538.

- ^ Livingston MG, Livingston HM (April 1996). "Monoamine oxidase inhibitors. An update on drug interactions". Drug Safety. 14 (4): 219–27. doi:10.2165/00002018-199614040-00002. PMID 8713690. S2CID 46742172.

- ^ Nair NP, Ahmed SK, Kin NM (November 1993). "Biochemistry and pharmacology of reversible inhibitors of MAO-A agents: focus on moclobemide". Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 18 (5): 214–25. PMC 1188542. PMID 7905288.

- ^ Baldwin D, Rudge S (1993). "Moclobemide: a reversible inhibitor of monoamine oxidase type A". British Journal of Hospital Medicine. 49 (7): 497–9. PMID 8490690.

- ^ "FDA Approves Emsam (Selegiline) as First Drug Patch for Depression" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 28 February 2006. Archived from the original on 21 November 2009. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- ^ Lawrence KR, Adra M, Gillman PK (June 2006). "Serotonin toxicity associated with the use of linezolid: a review of postmarketing data". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 42 (11): 1578–83. doi:10.1086/503839. PMID 16652315.

- ^ A.M. Timperio; H.A. Kuiper & L. Zolla (February 2003). "Identification of a furazolidone metabolite responsible for the inhibition of amino oxidases". Xenobiotica. 33 (2): 153–167. doi:10.1080/0049825021000038459. PMID 12623758. S2CID 35868007.

- ^ Petzer A, Harvey BH, Wegener G, Petzer JP (February 2012). "Azure B, a metabolite of methylene blue, is a high-potency, reversible inhibitor of monoamine oxidase". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 258 (3): 403–9. Bibcode:2012ToxAP.258..403P. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2011.12.005. PMID 22197611.

- ^ "An option if other antidepressants haven't helped". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ^ Donskaya NS, Antonkina OA, Glukhan EN, Smirnov SK (1 July 2004). "Antidepressant Befol Synthesized Via Interaction of 4-Chloro-N-(3-chloropropyl)benzamide with Morpholine". Pharmaceutical Chemistry Journal. 0091-150X. 38 (7): 381–384. doi:10.1023/B:PHAC.0000048439.38383.5f. S2CID 29121452.

- ^ Chaurasiya, Narayan D.; Leon, Francisco; Muhammad, Ilias; Tekwani, Babu L. (4 July 2022). "Natural Products Inhibitors of Monoamine Oxidases—Potential New Drug Leads for Neuroprotection, Neurological Disorders, and Neuroblastoma". Molecules. 27 (13): 4297. doi:10.3390/molecules27134297. ISSN 1420-3049. PMC 9268457. PMID 35807542.

- ^ van Diermen, Daphne; Marston, Andrew; Bravo, Juan; Reist, Marianne; Carrupt, Pierre-Alain; Hostettmann, Kurt (18 March 2009). "Monoamine oxidase inhibition by Rhodiola rosea L. roots". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 122 (2): 397–401. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2009.01.007. ISSN 0378-8741. PMID 19168123.