Mon–Burmese script

| Mon–Burmese မွန်မြန်မာအက္ခရာ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | 7th century – present |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Languages | Burmese, Sanskrit, Pali, Mon, Shan, Rakhine, Jingpho, S'gaw Karen, Western Pwo Karen, Eastern Pwo Karen, Geba Karen, Kayah, Rumai Palaung, Khamti Shan, Aiton, Phake, Pa'O, Palaung |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Mymr (350), Myanmar (Burmese) |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Myanmar |

| |

| Brahmic scripts |

|---|

| The Brahmi script and its descendants |

The Mon–Burmese script (Burmese: မွန်မြန်မာအက္ခရာ, ⓘ; Mon: အက္ခရ်မန်ဗၟာ, ⓘ, Thai: อักษรมอญพม่า, ⓘ; also called the Mon script, Old Mon script, and Burmese script) is an abugida that derives from the Pallava Grantha script of southern India and later of Southeast Asia. It is the basis of the alphabets used for modern Burmese, Mon, Shan, Rakhine, Jingpho, and Karen.[3]

The Mon-Burmese script is distinguished from Khmer-derived scripts (e.g., Khmer and Thai) by its basis on Pali orthography (they traditionally lack Sanskrit letters representing the sibilants <ś> and <ṣ> and the vocalic sonorants <ṛ> and <ḷ>), the use of a virāma, and the round shape of letters.[4]

History

[edit]The Old Mon language might have been written in at least two scripts. The Old Mon script of Dvaravati (present-day central Thailand), derived from Grantha (Pallava), has conjecturally been dated to the 6th to 8th centuries AD.[5][note 1] The second Old Mon script was used in what is now Lower Burma (Lower Myanmar), and is believed to have been derived from Kadamba or Grantha. According to mainstream colonial period scholarship, the Dvaravati script was the parent of Burma Mon, which in turn was the parent of the Old Burmese script, and the Old Mon script of Haripunjaya (present-day northern Thailand).[note 2] However, according to a minority view, the Burma Mon script was derived from the Old Burmese script and has no relation to the Dvaravati Mon script, based on the claim that there is a four century gap between the first appearance of the Burma Mon script and the last appearance of the Dvaravati Mon script.[6] According to the then prevailing mainstream scholarship, Mon inscriptions from the Dvaravati period appeared in present-day northern Thailand and Laos.[5] Such a distribution, in tandem with archaeological evidence of Mon presence and inscriptions in lower Burma, suggests a contiguous Mon cultural space in lower Burma and Thailand.[citation needed] In addition, there are specifically Mon features in Burmese that were carried over from the earliest Mon inscriptions. For instance, the vowel letter အ has been used in Mon as a zero-consonant letter to indicate words that begin with a glottal stop. This feature was first attested in Burmese in the 12th century, and after the 15th century, became default practice for writing native words beginning with a glottal stop. In contrast to Burmese, Mon only uses the zero-consonant letter for syllables which cannot be notated by a vowel letter. Although Mon of the Dvaravati inscriptions differ from Mon inscriptions of the early second millennium, orthographical conventions connect it to the Mon of the Dvaravati inscriptions and set it apart from other scripts used in the region.[7] Given that Burmese is first attested during the Pagan era, the continuity of orthographical conventions in Mon inscriptions, and the differences between the Pyu script and the script used to write Mon and Burmese, scholarly consensus attributes the origin of the Burmese script to Mon.[8]

The first attestation of written Burmese is an inscription from 1035 CE, (or 984 CE, according to an 18th century recast inscription).[9] From then on, the Mon–Burmese script further developed in its two forms, while staying common to both languages, and only a few specific symbols differ between the Mon and Burmese variants of the script.[10] The calligraphy of modern Mon script follows that of modern Burmese. Burmese calligraphy originally followed a square format but the cursive format took hold in the 17th century when popular writing led to the wider use of palm leaves and folded paper known as parabaiks.[11] The script has undergone considerable modification to suit the evolving phonology of the Burmese language, but additional letters and diacritics have been added to adapt it to other languages; the Shan and Karen alphabets, for example, require additional tone markers.

The Mon–Burmese script has been borrowed and adapted twice by Tai peoples. Around the 14th century, a model of the Mon–Burmese script from northern Thailand was adapted for religious purposes, to correctly write Pali in full etymological spelling. This resulted in the Tai Tham script, which can also be described as a homogenous group of script variants including the Tham Lao, Tham Lanna, Tham Lü and Tham Khün variants. Around the 15th or 16th centuries, the Mon–Burmese script was borrowed and adapted again to write a Tai language of northern Burma. This adaptation resulted in the Shan alphabet, Tai Le script, Ahom script and Khamti script.[10] This group of scripts has been called the "Lik Tai" scripts or "Lik" scripts, and are used by various Tai peoples in northeastern India, northern Myanmar, southwestern Yunnan, and northwestern Laos. According to the scholar Warthon, evidence suggests that the ancestral Lik-Tai script was borrowed from the Mon–Burmese script in the fifteenth century, most probably in the polity of Mong Mao.[12] However, it is believed that the Ahom people had already adopted their script before migrating to the Brahmaputra Valley in the 13th century.[13] Furthermore, The scholar Daniels describes a Lik Tai script featured on a 1407 Ming dynasty scroll, which shows greater similarity to the Ahom script than to the Lik Tho Ngok (Tai Le) script.[14]

-

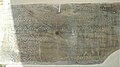

Hariphunchai National Museum, Lamphun, Thailand; Wat Saen Khao Ho Inscription, Mon alphabet and language

-

Hariphunchai National Museum, Lamphun, Thailand; Wat Ku Kut Inscription, Mon alphabet and language

-

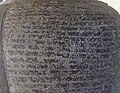

The Phra Pathom Mon inscription

-

Mon inscription on a Sima stone from Takaw-Kamain (Bilu Island), Mon State, Burma.

-

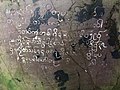

Myittha inscription, Mon side

-

Kaw-Hmu Mon inscription

-

Kaw-Hmu Mon inscription

Languages

[edit]

The script has been adapted for use in writing several languages of Burma other than Mon and Burmese, most notably in modern times Shan and S'gaw Karen. Early offshoots include Tai Tham script, Chakma script and the Lik-Tai group of scripts, which includes the Tai Le and Ahom scripts.[13] It is also used for the liturgical languages of Pali and Sanskrit.[15]

Characters

[edit]Displayed below are the 35 consonants of the Mon script.

က k IPA: /kaˀ/

|

ခ kh IPA: /kʰaˀ/

|

ဂ g IPA: /kɛ̤ˀ/

|

ဃ gh IPA: /kʰɛ̤ˀ/

|

င ṅ IPA: /ŋɛ̤ˀ/

|

စ c IPA: /caˀ/

|

ဆ ch IPA: /cʰaˀ/

|

ဇ j IPA: /cɛ̤ˀ/

|

ဈ jh IPA: /cʰɛ̤ˀ/

|

ဉ ñ IPA: /ɲɛ̤ˀ/

|

ဋ ṭ IPA: /taˀ/

|

ဌ ṭh IPA: /tʰaˀ/

|

ဍ ḍ IPA: /ɗaˀ/~[daˀ]

|

ဎ ḍh IPA: /tʰɛ̤ˀ/

|

ဏ ṇ IPA: /naˀ/

|

တ t IPA: /taˀ/

|

ထ th IPA: /tʰaˀ/

|

ဒ d IPA: /tɛ̤ˀ/

|

ဓ dh IPA: /tʰɛ̤ˀ/

|

န n IPA: /nɛ̤ˀ/

|

ပ p IPA: /paˀ/

|

ဖ ph IPA: /pʰaˀ/

|

ဗ b IPA: /pɛ̤ˀ/

|

ဘ bh IPA: /pʰɛ̤ˀ/

|

မ m IPA: /mɛ̤ˀ/

|

ယ y IPA: /jɛ̤ˀ/

|

ရ r IPA: /rɛ̤ˀ/

|

လ l IPA: /lɛ̤ˀ/

|

ဝ w IPA: /wɛ̤ˀ/

|

သ s IPA: /saˀ/

|

ဟ h IPA: /haˀ/

|

ဠ ḷ IPA: /laˀ/

|

ၜ b IPA: /ɓaˀ/

|

အ a IPA: /ʔaˀ/

|

ၝ mb IPA: /ɓɛ̤ˀ/

|

Unicode

[edit]The Mon–Burmese script was added to the Unicode Standard in September, 1999 with the release of version 3.0. Additional characters were added in subsequent releases.

Until 2005, most Burmese-language websites used an image-based, dynamically-generated method to display Burmese characters, often in GIF or JPEG. At the end of 2005, the Burmese NLP Research Lab announced a Myanmar OpenType font named Myanmar1. This font contains not only Unicode code points and glyphs but also the OpenType Layout (OTL) logic and rules. Their research center is based in Myanmar ICT Park, Yangon. Padauk, which was produced by SIL International, is Unicode-compliant. Initially, it required a Graphite engine, though now OpenType tables for Windows are in the current version of this font. Since the release of the Unicode 5.1 Standard on 4 April 2008, three Unicode 5.1 compliant fonts have been available under public license, including Myanmar3, Padauk and Parabaik.[16]

Many Burmese font makers have created Burmese fonts including Win Innwa, CE Font, Myazedi, Zawgyi, Ponnya, and Mandalay. It is important to note that these Burmese fonts are not Unicode compliant, because they use unallocated code points (including those for the Latin script) in the Burmese block to manually deal with shaping—that would normally be done by a complex text layout engine—and they are not yet supported by Microsoft and other major software vendors. However, there are few Burmese language websites that have switched to Unicode rendering, with many websites continuing[as of?] to use a pseudo-Unicode font called Zawgyi (which uses codepoints allocated for minority languages and does not efficiently render diacritics, such as the size of ya-yit) or the GIF/JPG display method.

Burmese support in Microsoft Windows 8

[edit]Windows 8 includes a Unicode-compliant Burmese font named "Myanmar Text". Windows 8 also includes a Burmese keyboard layout.[citation needed] Due to the popularity of the font in this OS, Microsoft kept its support in Windows 10.

Blocks

[edit]The Unicode block Myanmar is U+1000–U+109F. It was added to the Unicode Standard in September 1999 with the release of version 3.0:

| Myanmar[1] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+100x | က | ခ | ဂ | ဃ | င | စ | ဆ | ဇ | ဈ | ဉ | ည | ဋ | ဌ | ဍ | ဎ | ဏ |

| U+101x | တ | ထ | ဒ | ဓ | န | ပ | ဖ | ဗ | ဘ | မ | ယ | ရ | လ | ဝ | သ | ဟ |

| U+102x | ဠ | အ | ဢ | ဣ | ဤ | ဥ | ဦ | ဧ | ဨ | ဩ | ဪ | ါ | ာ | ိ | ီ | ု |

| U+103x | ူ | ေ | ဲ | ဳ | ဴ | ဵ | ံ | ့ | း | ္ | ် | ျ | ြ | ွ | ှ | ဿ |

| U+104x | ၀ | ၁ | ၂ | ၃ | ၄ | ၅ | ၆ | ၇ | ၈ | ၉ | ၊ | ။ | ၌ | ၍ | ၎ | ၏ |

| U+105x | ၐ | ၑ | ၒ | ၓ | ၔ | ၕ | ၖ | ၗ | ၘ | ၙ | ၚ | ၛ | ၜ | ၝ | ၞ | ၟ |

| U+106x | ၠ | ၡ | ၢ | ၣ | ၤ | ၥ | ၦ | ၧ | ၨ | ၩ | ၪ | ၫ | ၬ | ၭ | ၮ | ၯ |

| U+107x | ၰ | ၱ | ၲ | ၳ | ၴ | ၵ | ၶ | ၷ | ၸ | ၹ | ၺ | ၻ | ၼ | ၽ | ၾ | ၿ |

| U+108x | ႀ | ႁ | ႂ | ႃ | ႄ | ႅ | ႆ | ႇ | ႈ | ႉ | ႊ | ႋ | ႌ | ႍ | ႎ | ႏ |

| U+109x | ႐ | ႑ | ႒ | ႓ | ႔ | ႕ | ႖ | ႗ | ႘ | ႙ | ႚ | ႛ | ႜ | ႝ | ႞ | ႟ |

Notes

| ||||||||||||||||

The Unicode block Myanmar Extended-A is U+AA60–U+AA7F. It was added to the Unicode Standard in October 2009 with the release of version 5.2:

| Myanmar Extended-A[1] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+AA6x | ꩠ | ꩡ | ꩢ | ꩣ | ꩤ | ꩥ | ꩦ | ꩧ | ꩨ | ꩩ | ꩪ | ꩫ | ꩬ | ꩭ | ꩮ | ꩯ |

| U+AA7x | ꩰ | ꩱ | ꩲ | ꩳ | ꩴ | ꩵ | ꩶ | ꩷ | ꩸ | ꩹ | ꩺ | ꩻ | ꩼ | ꩽ | ꩾ | ꩿ |

Notes

| ||||||||||||||||

The Unicode block Myanmar Extended-B is U+A9E0–U+A9FF. It was added to the Unicode Standard in June 2014 with the release of version 7.0:

| Myanmar Extended-B[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+A9Ex | ꧠ | ꧡ | ꧢ | ꧣ | ꧤ | ꧥ | ꧦ | ꧧ | ꧨ | ꧩ | ꧪ | ꧫ | ꧬ | ꧭ | ꧮ | ꧯ |

| U+A9Fx | ꧰ | ꧱ | ꧲ | ꧳ | ꧴ | ꧵ | ꧶ | ꧷ | ꧸ | ꧹ | ꧺ | ꧻ | ꧼ | ꧽ | ꧾ | |

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

The Unicode block Myanmar Extended-C is U+116D0–U+116FF. It was added to the Unicode Standard in September 2024 with the release of version 16.0:

| Myanmar Extended-C[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+116Dx | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| U+116Ex | | | | | ||||||||||||

| U+116Fx | ||||||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ (Aung-Thwin 2005: 161–162): Of the 25 Mon inscriptions recovered in present-day Thailand, only one of them is securely dated—to 1504. The rest have been dated based on what historians believed the kingdom of Dvaravati existed, to around the 7th century per Chinese references to a kingdom, which historians take to be Dvaravati, in the region. According to Aung-Thwin, the existence of Dvaravati does not automatically mean the script also existed in the same period.

- ^ (Aung-Thwin 2005: 160–167) Charles Duroiselle, Director of the Burma Archaeological Survey, conjectured in 1921 that Mon was derived from Kadamba (Old Telugu–Canarese), and perhaps with influences from Grantha. G.H. Luce, not a linguist, in 1924 asserted that the Dvaravati script of Grantha origin was the parent of Burma Mon. Neither provided any proof. Luce's and Duroiselle's conjectures have never been verified or reconciled. In the 1960s, Tha Myat, a self-taught linguist, published books showing the Pyu origin of the Burmese script. But Tha Myat's books, written in Burmese, never got noticed by Western scholars. Per Aung-Thwin, as of 2005 (his book was published in 2005), there had been no scholarly debate on the origins of the Burmese script or the present-day Mon script. The colonial period scholarship's conjectures have been taken as fact, and no one has reviewed the assessments when additional evidence since points to the Burmese script being the parent of Burma Mon.

References

[edit]- ^ Aung-Thwin (2005): 167–178, 197–200

- ^ a b Diringer, David (1948). Alphabet a key to the history of mankind. p. 411.

- ^ Hosken, Martin. (2012). "Representing Myanmar in Unicode: Details and Examples" (ver. 4). Unicode Technical Note 11.

- ^ Jenny, Mathias (2021-08-23), Sidwell, Paul; Jenny, Mathias (eds.), "Writing systems of MSEA", The Languages and Linguistics of Mainland Southeast Asia: A comprehensive guide, De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 879–906, doi:10.1515/9783110558142-036, ISBN 978-3-11-055814-2, retrieved 2024-12-06

- ^ a b Bauer 1991: 35

- ^ Aung-Thwin 2005: 177–178

- ^ Hideo 2013

- ^ Jenny 2015: 2

- ^ Aung-Thwin 2005: 187–188

- ^ a b Ferlus, Michel (Jun 1999). "Les dialectes et les écritures des Tai (Thai) du Nghệ An (Vietnam)". Treizièmes Journées de Linguistique d'Asie Orientale. Paris, France.

- ^ Lieberman 2003: 136

- ^ Wharton, David (2017). Language, Orthography and Buddhist Manuscript Culture of the Tai Nuea: An Apocryphal Jātaka Text in Mueang Sing, Laos (PhD thesis). Universität Passau. p. 518. urn:nbn:de:bvb:739-opus4-5236.

- ^ a b Terwiel, B. J., & Wichasin, R. (eds.), (1992). Tai Ahoms and the stars: three ritual texts to ward off danger. Ithaca, NY: Southeast Asia Program.

- ^ Daniels, Christian (2012). "Script without Buddhism: Burmese Influence on the Tay (Shan) Script of Mäng2 Maaw2 as Seen in a Chinese Scroll Painting of 1407". International Journal of Asian Studies. 9 (2): 170–171. doi:10.1017/S1479591412000010. S2CID 143348310.

- ^ Sawada, Hideo. (2013). "Some Properties of Burmese Script" Archived 2016-10-20 at the Wayback Machine. Presented at the 23rd Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society (SEALS23), Chulalongkorn University, Thailand.

- ^ Zawgyi.ORG Developer site Archived 7 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography

[edit]- Aung-Thwin, Michael (2005). The Mists of Rāmañña: The Legend that was Lower Burma (illustrated ed.). Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2886-8.

- Bauer, Christian (1991). "Notes on Mon Epigraphy". Journal of the Siam Society. 79 (1): 35.

- Lieberman, Victor B. (2003). Strange Parallels: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800–1830, volume 1, Integration on the Mainland. Cambridge University Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-521-80496-7.

- Stadtner, Donald M. (2008). "The Mon of Lower Burma". Journal of the Siam Society. 96: 198.

- Sawada, Hideo (2013). "Some Properties of Burmese Script" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-10-20. Retrieved 2016-01-23.

- Jenny, Mathias (2015). "Foreign Influence in the Burmese Language" (PDF).