Mir Shams-ud-Din Araqi

Mir Syed Shams-ud-Din Arāqi | |

|---|---|

میر شمس الدین اراقی | |

| |

| Personal life | |

| Born | 13 September 1440 (13 Rajab 861 AH) |

| Died | 28 January 1515 (aged 74) (01 Rabīʿ al-ʾAwwal 936 AH) |

| Resting place | Tomb of Shams-ud-Din Araqi, Chadoora, Kashmir Valley |

| Other names | Hazrat Syed Muhammad Musavi Isfahani |

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Shia Islam |

| Tariqa | Noorbakshia |

| Senior posting | |

| Based in | Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir |

| Post | Allama, Sufi cleric |

| Period in office | 1460–1515 |

| Predecessor | Mir Syed Ibrahim Musavi Isfahani |

| Successor | Mir Syed Daniyal Araqi |

| Part of a series on Sufi Islam |

| Noorbakhshia |

|---|

|

Mir Syed Shams-ud-Din Muhammad Arāqi[a] (Persian: میر شمس الدین محمد عراقی; c. 1440–1515 CE), was an Iranian Sufi saint.[4] Araqi was part of the order of Twelver Shia Sufis in Jammu and Kashmir who greatly influenced the social fabric of the Kashmir Valley and its surrounding regions.

Early life

[edit]Araqi was born in Kundala, a village near Suliqan to Darvish Ibrahim and Firuza Khatun. Darvish was a Sufi dedicated to Muhammad Nurbakhsh Qahistani while Firuza was descended from a Sayyid family from Qazvin.[5] As an adolescent, Araqi first encountered Nurbakhsh when the latter arrived in Suliqan but was told by Nurbakhsh himself not to engage in Sufi devotions due to family responsibilities. Soon after Nurbaksh's death around 1464, Araqi visited his grave and chose to follow the Noorbakshia path.[5]

Career in Herat

[edit]Soon after deciding to join the Noorbakshia order, Araqi spent nineteen years traveling and studying under various khanqah masters throughout Iran and Iraq. He eventually rose in the order's hierarchy and became settled in Durusht near Tehran under master Qasim Fayzbakhsh.[6]

When Timurid Sultan Husayn Bayqara invited Qasim to join his court at Herat, Araqi accompanied him. In Herat, Araqi apparently undertook a mission for Bayqara to investigate if a king from Iraq was planning to conquer parts of Khurasan under Timurid control. Once back in Herat after determining that the plans were untrue, Araqi and Qasim were given rewards and elevated positions within the court.[7]

Soon after the earlier mission, Araqi was sent as an envoy of Bayqara to Kashmir under the pretext of a diplomatic visit to the Kashmir royal court and gathering medicinal herbs for Qasim.[7] However, the embassy is not mentioned in Timurid histories and Qasim seems to have been the main supporter of the mission, likely meaning that the main purpose of the assignment was to expand the Noorbakshia order into Kashmir.[8]

Career in Kashmir

[edit]From Herat, Araqi traveled to Multan and eventually arrived in Kashmir at around 1483. He was greeted by Sultan Hasan Shah and subsequently resided in Kashmir for 8 years.[9] Initially taking the role of an ambassador, he eventually became an independent religious missionary. Araqi established himself in various khanqahs or other venues during his stay and attracted followers to his order. However, Araqi also faced several political conflicts with other scholars in the royal court during this period.[10] Around 1491, Araqi left Kashmir to return to Durusht but appointed one of his students, Mulla Ismail, to lead the order.[11]

Araqi returned to Kashmir in 1503 after hearing that Mulla Ismail was allegedly going against the rules given to him over initiation and expansion of the order, although the unforeseen success of the order was likely what actually convinced Araqi to return. The Noorbakshia order throughout the rest of Araqi's life saw the order attain significant success along with influence in Kashmiri politics.[12] He was able to convert several nobles and other powerful figures to the order.[12]

Exile in Baltistan

[edit]For a brief period when Araqi was banished from Kashmir in 1505 due to political tensions at the court, he along with 50 other disciples sought refuge at Skardu in Baltistan.[13] The local rulers welcomed him and treated him as a royal guest.[14] He would soon return to Kashmir after staying in Baltistan for around 2 months.[15] According to local traditions, Araqi and his followers converted many local Balti to the order. Araqi chose one of his disciples, Haidar Hafiz, to stay in Skardu and continue to lead the order there.[13]

Death

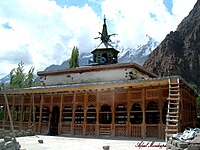

[edit]While sources do not give a specific year in which Araqi died, common dates given include 1515[16] or 1526.[17] He was buried at Zaddibal in Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir.[16] His body was later shifted to Chadoora for unknown reasons, where he is currently buried at a Sufi Islamic shrine.[16]

Legacy

[edit]He is considered by some to be the effective founder of Shia Islam in Ladakh and Gilgit–Baltistan, as well as in the rest of Jammu and Kashmir and its adjoining areas.[18][16] After arriving in Srinagar, he established his Khanqah in the suburbs (now known as Zaddibal), which would later go on to produce many of Kashmir's future military leaders. He was best known for influencing the nobles of the Chak clan to embrace the Noorbakshia Sufi Islamic faith as well as Shia Islam as a whole. Araqi translated the Fiqh-i-Ahwat (book of jurisprudence), which was written in Arabic by his teacher, Syed Muhammad Noorbaksh.

See also

[edit]- Tomb of Shams-ud-Din Araqi

- Persecution of Kashmiri Shias

- Tafazzul Husain Kashmiri

- Shia Islam in the Indian subcontinent

Notes

[edit]Sources

[edit]- Bashir, Shahzad (2003). Messianic Hopes and Mystical Visions: The Nūrbakhshīya Between Medieval and Modern Islam. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 9781570034954

References

[edit]- ^ Abdullah, Darakhshan (November 1991). Religious Policy of the Sultans of Kashmir (1320-1586 A. D.) (PDF). Post-Graduate Department of History, University of Kashmir – via Core.

- ^ Kumar, Radha (2018). Paradise at War. Aleph. Rupa. p. 10. ISBN 9789388292122.

- ^ a b Hanif, N. (2002). Biographical Encyclopaedia of Sufis: Central Asia and Middle East. Sarup & Sons. pp. 366, 438. ISBN 978-81-7625-266-9.

- ^ Shiri Ram Bakshi (1997). Kashmir: Valley and Its Culture. Sarup & Sons. p. 231. ISBN 978-81-85431-97-0.

- ^ a b Bashir, Shahzad (2003). Messianic Hopes and Mystical Visions: The Nūrbakhshīya Between Medieval and Modern Islam. University of South Carolina Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-1-57003-495-4.

- ^ Bashir 2003, p. 203.

- ^ a b Bashir 2003, p. 205.

- ^ Bashir 2003, pp. 205-206.

- ^ Bashir 2003, p. 206

- ^ Bashir 2003, pp. 207-214

- ^ Bashir 2003, pp. 215- 219

- ^ a b Bashir 2003, pp. 220-224

- ^ a b Holzworth, Wolfgang (1997). "Islam in Baltistan: Problems of Research on the Formative Period". In Stellrecht, Irmtraud (ed.). The Past in the Present: Horizons of Remembering in the Pakistan Himalaya. Rüdiger Köppe. ISBN 978-3-89645-152-1.

- ^ Aabedi, Zain-ul-aabedin (2009). Emergence of Islam in Ladakh. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-81-269-1047-2.

- ^ Bashir 2003, p. 226

- ^ a b c d تاریخ شیعیان کشمیر [History of the Shiites of Kashmir].

- ^ Bashir 2003, p. 224

- ^ Yatoo, Altaf Hussain (2012). The Islamization of Kashmir: A Study of Muslim Missionaries. Kashmir, India: Gulshan Books. ISBN 9788183391467.

External links

[edit] Quotations related to Mir Shams-ud-Din Araqi at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Mir Shams-ud-Din Araqi at Wikiquote