Min Razagyi

| Raza II of Mrauk-U မင်းရာဇာကြီး Thado Dhamma Raza Salim Shah (ဆောလိမ်သျှာ) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| King of Arakan | |||||

| Reign | 4 July [O.S. 24 June] 1593 – 4 July [O.S. 24 June] 1612 | ||||

| Predecessor | Phalaung | ||||

| Successor | Khamaung | ||||

| Chief Minister | Maha Pyinnya Kyaw | ||||

| Born | 1557/1558 (Monday born)[note 1] Sittantin | ||||

| Died | 4 July [O.S. 24 June] 1612 (aged 54) Wednesday, 8th waxing of Waso 974 ME[1] Mrauk-U | ||||

| Consort | Wizala (chief queen) and eight major queens 11 minor queens[1] | ||||

| Issue | More than 15 children including Khamaung[1] | ||||

| |||||

| Father | Min Phalaung | ||||

| Mother | Saw Mi Taw | ||||

| Religion | Theravada Buddhism | ||||

Min Razagyi (Arakanese and Burmese: မင်းရာဇာကြီး, Arakanese pronunciation: [máɴ ɹàzà ɡɹí], Burmese pronunciation: [mɪ́ɴ jàzà dʑí]; c. 1557–1612), also known as Salim Shah, was king of Arakan from 1593 to 1612. His early reign marked the continued ascent of the coastal kingdom, which reached full flight in 1599 by defeating its nemesis Toungoo Dynasty, and temporarily controlling the Bay of Bengal coastline from the Sundarbans to the Gulf of Martaban until 1603.[2][3] But the second half of his reign saw the limits of his power: he lost the Lower Burmese coastline in 1603 and a large part of Bengal coastline in 1609 due to insurrections by Portuguese mercenaries. He died in 1612 while struggling to deal with Portuguese raids on the Arakan coast itself.[4]

Early life

[edit]The future king was born to Princess Saw Mi Taw (စောမိတော်, [sɔ́ mḭ dɔ̀] and Prince Phalaung, governor of Sittantin, in 1557/1558. His parents were half-siblings, both children of King Min Bin. He was likely born in Sittantin where his father was governor from early 1550s to 1572.[note 2] In 1572, Phalaung succeeded King Sekkya, and made his eldest son Razagyi, only 15, heir-apparent with the style of Thado Dhamma Raza. At the coronation ceremony, Razagyi was married off to Princess Nan Htet Phwa (နန်းထက်ဖွား, [náɴ tʰɛʔ pʰwá]), daughter of Sekkya and his first cousin, once removed.[5]

Heir-apparent

[edit]Razagyi loyally served his father for the duration of his father's 21-year reign. His most prominent contribution during this period recorded in the Arakanese chronicles came in 1575 when he led a well armed naval and land forces in an expedition to Tripura. The expedition was a success. The Arakanese forces, aided by Portuguese mercenaries and firearms, easily captured the Tripuri capital, after which Tripura agreed to pay tribute.[6][7] In the later years, however, Phalaung began relying on his middle son Thado Minsaw, who became the commander-in-chief, for military expeditions, and appointed him king of Bengal. Thado Minsaw, now based out of Chittagong, became Razagyi's main rival to succeed the throne.[8]

Reign

[edit]Consolidation

[edit]On 4 July [O.S. 24 June] 1593, King Phalaung died, and Razagyi succeeded without any opposition. The 35-year-old new king took the reign name of Raza in the honor of his great-great-grandfather King Raza I (r. 1502–1513), and also took the Persian title of Salim Shah as sultan of Bengal. All the vassals of the kingdom, including Thado Minsaw, came to the court, and pledged allegiance to the new king. For his part, he re-appointed Thado Minsaw as king of Bengal, essentially the viceroy of northern territories,[9] which included Chittagong, Noakhali and Tippera.[7]

The peace between the brothers did not last. In 1595, Thado Minsaw at Chittagong revolted with support from chiefs of Tripura and other northern districts. But the rest of the country, and the majority of Portuguese mercenaries, remained loyal to Razagyi. (A major component of Arakan's powerful military since the 1530s had been its many Portuguese mercenaries and their firearms.) When Razagyi marched to Chittagong with a massive force after the rainy season, Thado Minsaw lost nerve and submitted without a fight. Razagyi's armies followed up onto northern districts and Tripura, and by February 1596 (Tabodwe 957 ME), had reestablished control.[9]

Victory over Toungoo Empire

[edit]

Razagyi was now the undisputed leader of a prosperous and militarily powerful kingdom that stretched from the Sundarbans in the northwest to Cape Negrais in the south. The kingdom's relative power greatly improved in the following year, when its nemesis Toungoo Empire, which had tried to conquer the coastal kingdom in (1545–1547) and (1580–1581), was teetering on collapse. King Nanda at Pegu (Bago) now controlled only parts of Lower Burma, and faced rebellions everywhere, including the city of Toungoo, the ancestral home of the Dynasty.[11]

Sensing the weakness, Razagyi readily agreed to an alliance with one of the rebel leaders, Minye Thihathu of Toungoo city in 1597. They agreed to a joint attack on whatever remained of the empire.[12] This was a major departure from the policy of previous Arakanese kings, who since the 1550s had carefully avoided interfering in mainland affairs. He ordered a massive mobilization drive across the entire kingdom, from the Ganges delta and Tripura in the north to Thandwe in the south. By late 1598, he had assembled a massive land and naval invasion force, whose combined strength may have been as high as 30,000 troops.[note 3]

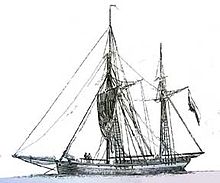

On 10 November [O.S. 31 October] 1598 (Tuesday, 11th waxing of Tazaungmon 960 ME), the combined invasion force left Mrauk-U. The king himself led the army while he appointed his eldest son and heir-apparent Prince Khamaung to lead the naval fleet consisted of 300 war boats.[12] Under Khamaung were Portuguese mercenaries led by Filipe de Brito e Nicote.[4] At Thandwe, the invasion forces parted. The army crossed the Rakhine Yoma range through the passes toward Pegu while the navy went around Cape Negrais toward the key port of Syriam (Thanlyin), which it seized in March 1599 (Tabaung 960 ME).[13] In April, Arakanese forces marched to Pegu, and effected a junction with rebel Toungoo forces. The combined forces now laid siege to the city. The siege lasted until December when Nanda surrendered.[14]

The victors took over the city, and divided the enormous wealth of Pegu, accumulated over the past 60 years as the capital of Toungoo Empire. The gold, silver and precious stones were equally divided. The Arakanese share also included several brazen cannon, 30 Khmer bronze statues, and a white elephant.[15][16] (Razagyi also raised Princess Khin Ma Hnaung, a daughter of Nanda, as his queen.[17]) Rebel Toungoo forces returned with their share of the loot to Toungoo on 15 February 1600 (2nd waxing of Tabaung 961 ME), leaving the Arakanese in charge of the city.[18]

The Arakanese forces remained in Pegu for another month. Razagyi did not have the manpower to hold all of Lower Burma but he nonetheless wanted to make sure that it remained weak for a long time. His plan was to destroy the infrastructure and deplete the manpower of interior Lower Burma as much as possible, and hold key strategic ports of Lower Burma. As such, he deported 3,000 households to Arakan, and burned down the entire city, including the Grand Palace of King Bayinnaung.[15] He then moved down to the port of Syriam, which he planned to hold with a garrison.[15]

Siamese invasion

[edit]In March, as the main portion of the Arakanese forces at Syriam were about to return home, the Siamese forces led by King Naresuan arrived at Pegu, only to find that the city had been looted and burned down. Naresuan hastily followed up to Toungoo, laying siege to the city in April 1600. As an ally of Toungoo city, Razagyi ordered his troops to attack Siamese supply lines by land and sea. The Arakanese navy intercepted Siamese supply ships while the army cut the remaining supply lines. On 6 May [O.S. 26 April] 1600, Naresuan hastily retreated back but the Siamese forces suffered heavy losses from Arakanese ambushes in retreat. Only a small portion finally reached Martaban.[15][19]

It proved to be the last invasion of mainland Burma by Siam. At Syriam, Razagyi assigned De Brito, the leader of Portuguese mercenaries in his navy, to lead the garrison, and returned home by sea.[15] The Chief Minister Maha Pyinnya Kyaw, the trusted minister of the king, died on the return trip, and was cremated and buried at the Mawtinzun Pagoda near Negrais. The 3,000 households brought from Pegu were settled at Urittaung and along the Mayu river and at Thandwe.[4]

Mrauk-U Empire and Portuguese insurrections

[edit]

Between 1600 and 1603, the Kingdom of Mrauk-U with its powerful navy controlled over 1600 km (1000 miles) of the Bay of Bengal coastline from the Sundarbans in West Bengal to the Gulf of Martaban. However, the navy was heavily dependent on Portuguese mercenaries and their firearms. Though the loyalty of the mercenaries was always suspect, Razagyi needed them to hold his maritime empire. He made De Brito governor of Syriam in June 1600.[20] But De Brito revolted in March 1603 with support from the Portuguese viceroy of Goa.[note 4] In late 1603, Razagyi sent the navy led by the crown prince Khamaung to Syriam but the navy was ambushed by four Portuguese ships awaiting by the Hainggyi island near Negrais. Khamaung himself was captured. Razagyi himself followed up with another 300-boat navy, and with the Toungoo forces jointly laid siege to the city. But Syriam defenses held. In the following negotiations, in 1604, Razagyi agreed to a ransom of 50,000 ducats for the release of the crown prince, and to Syriam's status as a Portuguese colony.[21][22]

After the setback, Razagyi began to fear the loyalty of other Portuguese in his service. Concerned that De Brito would take over the strategic island of Dianga opposite Chittagong, he had 600 Portuguese settlers there killed. Only a few Portuguese escaped. In 1608, the king offered to let the Dutch East India Company trade and build fortifications in return for their help in driving out the Portuguese but the Dutch did not accept the offer because of their heavy commitments elsewhere. In 1609, one of the escapees of Dianga, Sebastian Gonzales Tibao came back with 400 well-armed Portuguese and seized the Sandwip island, wiping out over 3000 Afghan pirates there. It was a major loss as the island was a strategic port and trade center that commanded the Brahmaputra and Ganges rivers. Moreover, the governor of Chittagong, the king's younger brother, after a quarrel with the king, fled and joined Gonzales, marrying his daughter off to Tibao, who promptly baptized her.[4] The refugee governor died suddenly, probably from poison, and Tibao seized all of his treasure.[23]

Razagyi was furious but he faced an even more urgent threat. Hearing that the Moghul governor of Bengal was planning an attack on Noakhali at the mouth of the Ganges, he agreed to an alliance with Tibao. To secure the rear, he sent an embassy to the court of King Anaukpetlun in December 1609.[24] In 1610, he sent the navy to fight the Moghul transgressions. At Sandwip, Tibao brazenly broke the alliance, and seized the entire fleet by "the simple expedient of murdering its captains at a council". Tibao and his crew then began raiding the Arakanese coast, once reaching all the way up the Lemro river and taking away the king's gold and ivory barge.[4]

Religious affairs

[edit]The king enlarged the Andaw-thein Ordination Hall in order to house a tooth relic of the Buddha he brought back from his pilgrimage to Ceylon, either in 1596 or 1606–1607.[note 5] He also dedicated a new ordination hall at the Mahamuni Temple on 7 January 1609.[note 6]

Death

[edit]The king never solved the problem of Portuguese raids. He died on 4 July [O.S. 24 June] 1612, and was succeeded by his eldest son Khamaung.[1]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Based on the chronicle reporting of his age at accession and death, he was born some time between 7 June 1557 and 20 June 1558. Per (Sandamala Linkara Vol. 2 1999: 54, 87), he came to power at age 35 on 6th waxing of Waso 955 ME, and died on 8th waxing of Waso 974 ME at age 54. This means he was born after 8th waxing of Waso 919 ME (4 June 1557) but before 6th waxing of Waso 920 ME (21 June 1558). And since he was born on a Monday, the range is 7 June 1557 to 20 June 1558.

- ^ The chronicle Rakhine Razawin Thit (Sandamala Linkara Vol. 2 1999: 34–35) says his father Phalaung was given Sittantin (စစ်တံတင်) in fief by King Min Bin (r. 1531–1554). Phalaung continued to be the governor of Sittantin till 1572.

- ^ Chronicles (Sandamala Linkara Vol. 2 1999: 77–78) report an order magnitude higher, 300,000. But per (Harvey 1925: 333–336), the troop numbers reported in Burmese chronicles should be taken an order of magnitude lower. The lower 30,000 figure may still be too high for the coastal kingdom even with its control over East Bengal since the far larger Toungoo Empire under King Nanda could only raise about 25,000 troops in his 1586–1587 invasion of Siam per (Harvey 1925: 334). Even King Bayinnaung of Toungoo, who commanded loyalty of his vassals, typically raised between 25,000 to 37,000 men, outside of his two Siamese campaigns, which raised 60,000 and 70,000 troops.

- ^ (Than Tun 2011: 135): De Brito was appointed governor of Syriam by the viceroy of Goa, and left Goa in March 1603. He probably got back to Syriam in March or April 1603.

- ^ (Gutman 2001: 112) says he rebuilt the Andaw Thein in 1596 after the Ceylon trip. But chronicles (Sandamala Linkara Vol. 2 1999: 84) mention just one pilgrimage to Ceylon, leaving for the island state in Tazaungmon 968 ME (31 October 1606 to 28 November 1606 NS). This means he probably had the structure enlarged in 1607.

- ^ Chronicles (Sandamala Linkara Vol. 2 1999: 84) say he opened the hall on Wednesday, 2nd waxing of Tabodwe 969 ME, which translates to Saturday, 19 January 1608. The year 969 is likely a recording error. The correct date is probably 2nd waxing of Tabodwe 970 ME, which translates to Wednesday, 7 January 1609.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Sandamala Linkara Vol. 2 1999: 87

- ^ Myint-U 2006: 77

- ^ Topich, Leitich 2013: 21

- ^ a b c d e Harvey 1925: 141–142

- ^ Sandamala Linkara Vol. 2 1999: 48

- ^ Sandamala Linkara Vol. 2 1999: 49

- ^ a b Phayre 1967: 173

- ^ Sandamala Linkara Vol. 2 1999: 51–52

- ^ a b Sandamala Linkara Vol. 2 1999: 76–77

- ^ Harvey 1925: 168, 183, 268

- ^ Harvey 1925: 181–182

- ^ a b Sandamala Linkara Vol. 2 1999: 77–78

- ^ Hmannan Vol. 3 2003: 100

- ^ Hmannan Vol. 3 2003: 101

- ^ a b c d e Harvey 1925: 182–183

- ^ Htin Aung 1967: 133–134

- ^ Sandamala Linkara Vol. 2 1999: 80–81

- ^ Hmannan Vol. 3 2003: 103

- ^ Htin Aung 1967: 134

- ^ Than Tun 2011: 135

- ^ Maha Yazawin Vol. 3 2006: 107

- ^ Harvey 1925: 185

- ^ Hall 1960: 4

- ^ (Sandamala Linkara Vol. 2 1999: 84): Tuesday, 4th waxing of Natdaw 971 ME = 1 December 1609

Bibliography

[edit]- Charney, Michael W. (1993). Arakan, Min Razagyi, and the Portuguese:the relationship between the growth of Arakanese imperial power and Portuguese mercenaries on the fringe of Southeast Asia. London: SOAS Bulletin of Burma Research. ISSN 1479-8484.

- Gutman, Pamela (2001). Burma's Lost Kingdoms: Splendours of Arakan. Bangkok: Orchid Press. ISBN 974-8304-98-1.

- Hall, D.G.E. (1960). The Rise and Fall of the Kingdom of Mrohaung in Arakan.

- Harvey, G. E. (1925). History of Burma: From the Earliest Times to 10 March 1824. London: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd.

- Htin Aung, Maung (1967). A History of Burma. New York and London: Cambridge University Press.

- Myint-U, Thant (2006). The River of Lost Footsteps—Histories of Burma. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-16342-6.

- Phayre, Lt. Gen. Sir Arthur P. (1883). History of Burma (1967 ed.). London: Susil Gupta.

- Royal Historical Commission of Burma (1832). Hmannan Yazawin (in Burmese). Vol. 1–3 (2003 ed.). Yangon: Ministry of Information, Myanmar.

- Sandamala Linkara, Ashin (1931). Rakhine Yazawinthit Kyan (in Burmese). Vol. 1–2 (1997–1999 ed.). Yangon: Tetlan Sarpay.

- Than Tun (2011). "23. Nga Zinga and Thida". Myanmar History Briefs (in Burmese). Yangon: Gangaw Myaing.

- Topich, William J.; Keith A. Leitich (2013). The History of Myanmar. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313357244.