Mimas

| |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | William Herschel |

| Discovery date | 17 September 1789[1] |

| Designations | |

Designation | Saturn I |

| Pronunciation | /ˈmaɪməs/[2] or as Greco-Latin Mimas (approximated /ˈmiːməs/) |

Named after | Μίμας Mimās |

| Adjectives | Mimantean,[3] Mimantian[4] (both /mɪˈmæntiən/) |

| Orbital characteristics [5] | |

| Periapsis | 181902 km |

| Apoapsis | 189176 km |

| 185539 km | |

| Eccentricity | 0.0196 |

| 0.942421959 d | |

Average orbital speed | 14.28 km/s (calculated) |

| Inclination | 1.574° (to Saturn's equator) |

| Satellite of | Saturn |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | 415.6 × 393.4 × 381.2 km (0.0311 Earths)[6] |

| 198.2±0.4 km[6][7] | |

| 490000–500000 km2 | |

| Volume | 32600000±200000 km3 |

| Mass | (3.75094±0.00023)×1019 kg [7] (6.3×10−6 Earths) |

Mean density | 1.1501±0.0070 g/cm3[7] |

| 0.064 m/s2 (0.00648 g) | |

| 0.159 km/s | |

| synchronous | |

| zero | |

| Albedo | 0.962±0.004 (geometric)[8] |

| Temperature | ≈ 64 K |

| 12.9 [9] | |

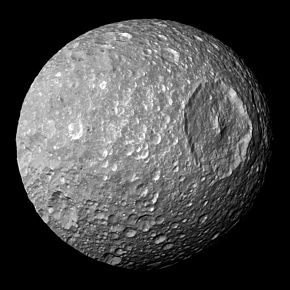

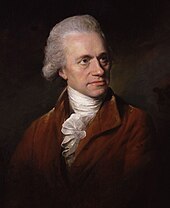

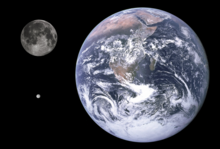

Mimas, also designated Saturn I, is the seventh-largest natural satellite of Saturn. With a mean diameter of 396.4 kilometres or 246.3 miles, Mimas is the smallest astronomical body known to be roughly rounded in shape due to its own gravity. Mimas's low density, 1.15 g/cm3, indicates that it is composed mostly of water ice with only a small amount of rock, and study of Mimas's motion suggests that it may have a liquid ocean beneath its surface ice. The surface of Mimas is heavily cratered and shows little signs of recent geological activity. A notable feature of Mimas's surface is Herschel, one of the largest craters relative to the size of the parent body in the Solar System. Herschel measures 139 kilometres (86 miles) across, about one-third of Mimas's mean diameter,[10] and formed from an extremely energetic impact event. The crater's name is derived from the discoverer of Mimas, William Herschel, in 1789. The moon's presence has created one of the largest 'gaps' in Saturn's ring, named the Cassini Division, due to orbital resonance destabilising the particles' orbit there.

Discovery

[edit]

Mimas was discovered by the astronomer William Herschel on 17 September 1789. He recorded his discovery as follows:

I continued my observations constantly, whenever the weather would permit; and the great light of the forty-feet speculum was now of so much use, that I also, on the 17th of September, detected the seventh satellite, when it was at its greatest preceding elongation.[11][12]

— William Herschel

The 40-foot telescope was a metal mirror reflecting telescope built by Herschel, with a 48-inch (1,200 mm) aperture. The 40 feet refers to the length of the focus, not the aperture diameter as is more common with modern telescopes.

Name

[edit]

Mimas is named after one of the Giants in Greek mythology, Mimas. The names of all seven then-known satellites of Saturn, including Mimas, were suggested by William Herschel's son John in his 1847 publication Results of Astronomical Observations made at the Cape of Good Hope.[13][14] Saturn (the Roman equivalent of Cronus in Greek mythology) was the leader of the Titans, the generation before the Gods, and rulers of the world for some time, while the Giants were the subsequent generation, and each group fought a great struggle against Zeus and the Olympians.

The customary English pronunciation of the name is /ˈmaɪməs/,[15] or sometimes /ˈmiːməs/.[16]

The Greek and Latin root of the name is Mimant- (cf. Italian Mimante, Russian Мимант for the mythological figure),[17] and so the English adjectival form is Mimantean[18] or Mimantian,[19] either spelling pronounced /maɪˈmæntiən/ ~ /mɪˈmæntiən/.[20]

Physical characteristics

[edit]

Mimas is the smallest and innermost of Saturn's major moons. The surface area of Mimas is slightly less than the land area of Spain or California. The low density of Mimas, 1.15 g/cm3, indicates that it is composed mostly of water ice with only a small amount of rock. As a result of the tidal forces acting on it, Mimas is noticeably oblate; its longest axis is about 10% longer than the shortest. The ellipsoidal shape of Mimas is especially noticeable in some recent [when?] images from the Cassini probe. Mimas's most distinctive feature is a giant impact crater 139 km (86 mi) across, named Herschel after the discoverer of Mimas. Herschel's diameter is almost a third of Mimas's own diameter; its walls are approximately 5 km (3 mi) high, parts of its floor measure 10 km (6 mi) deep, and its central peak rises 6 km (4 mi) above the crater floor. If there were a crater of an equivalent scale on Earth (in relative size) it would be over 4,000 km (2,500 mi) in diameter, wider than Australia. The impact that made this crater must have nearly shattered Mimas: the surface antipodal to Herschel (opposite through the globe) is highly disrupted, indicating that the shock waves created by the Herschel impact propagated through the whole moon.[21] See for example figure 4 of[22]

The Mimantean surface is saturated with smaller impact craters, but no others are anywhere near the size of Herschel. Although Mimas is heavily cratered, the cratering is not uniform. Most of the surface is covered with craters larger than 40 km (25 mi) in diameter, but in the south polar region, there are generally no craters larger than 20 km (12 mi) in diameter.

Three types of geological features are officially recognised on Mimas: craters, chasmata (chasms), and catenae (crater chains).

By studying Mimas's movement, researchers have found that it has a water ocean beneath 20–30 km (12–19 mi) of surface ice. The ocean formed within the last 25 million years, perhaps even the last 2-3 million years, and is thought to be warmed by Saturn's tidal forces.[23]

Orbital resonances

[edit]A number of features in Saturn's rings are related to resonances with Mimas. Mimas is responsible for clearing the material from the Cassini Division, the gap between Saturn's two widest rings, the A Ring and B Ring. Particles in the Huygens Gap at the inner edge of the Cassini division are in a 2:1 orbital resonance with Mimas. They orbit twice for each orbit of Mimas. The repeated pulls by Mimas on the Cassini division particles, always in the same direction in space, force them into new orbits outside the gap. The boundary between the C and B rings is in a 3:1 resonance with Mimas. Recently, the G Ring was found to be in a 7:6 co-rotation eccentricity resonance[24][clarification needed] with Mimas; the ring's inner edge is about 15,000 km (9,300 mi) inside Mimas's orbit.[citation needed]

Mimas is also in a 2:1 mean-motion resonance with the larger moon Tethys, and in a 2:3 resonance with the outer F Ring shepherd moonlet, Pandora. A moon co-orbital with Mimas was reported by Stephen P. Synnott and Richard J. Terrile in 1982, but was never confirmed.[25][26]

Anomalous libration and subsurface ocean

[edit]In 2014, researchers noted that the librational motion of Mimas has a component that cannot be explained by its orbit alone, and concluded that it was due to either an interior that is not in hydrostatic equilibrium (an elongated core) or an internal ocean.[27] However, in 2017 it was concluded that the presence of an ocean in Mimas's interior would have led to surface tidal stresses comparable to or greater than those on tectonically active Europa. Thus, the lack of evidence for surface cracking or other tectonic activity on Mimas argues against the presence of such an ocean; as the formation of a core would have also produced an ocean and thus the nonexistent tidal stresses, that possibility is also unlikely.[28] The presence of an asymmetric mass anomaly associated with the crater Herschel was considered to be a more likely explanation for the libration.[28]

In 2022, scientists at the Southwest Research Institute identified a tidal heating model for Mimas that produced an internal ocean without any surface cracking or visible tidal stresses. The presence of an internal ocean concealed by a stable icy shell between 24 and 31 km in thickness was found to match the visual and librational characteristics of Mimas as observed by Cassini.[29] Continued measurements of Mimas's surface heat flux will be needed to confirm this hypothesis.[30]

On 7 February 2024, researchers at the Paris Observatory announced the discovery that Mimas's orbit apsidally precesses slower than predicted if it were a solid body, which further supports the existence of a subsurface ocean in Mimas. The researchers estimated the ocean to be located 20 to 30 km below the surface, consistent with previous estimates. The researchers suggest that Mimas's ocean must be very young, less than 25 million years old, to explain the lack of geological activity on Mimas's cratered surface.[31]

Exploration

[edit]Pioneer 11 flew by Saturn in 1979, and its closest approach to Mimas was 104,263 km on 1 September 1979.[32] Voyager 1 flew by in 1980, and Voyager 2 in 1981.

Mimas was imaged several times by the Cassini orbiter, which entered into orbit around Saturn in 2004. A close flyby occurred on 13 February 2010, when Cassini passed by Mimas at 9,500 km (5,900 mi).

In popular culture

[edit]

When seen from certain angles, Mimas resembles the Death Star, a fictional space station and superweapon known from the 1977 film Star Wars. Herschel resembles the concave disc of the Death Star's "superlaser". This is a coincidence, as the film was made nearly three years before Mimas was resolved well enough to see the crater.[33]

In 2010, NASA revealed a temperature map of Mimas, using images obtained by Cassini. The warmest regions, which are along one edge of Mimas, create a shape similar to the video game character Pac-Man, with Herschel Crater assuming the role of an "edible dot" or "power pellet" known from Pac-Man gameplay.[34][35][36]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Imago Mundi: La Découverte des satellites de Saturne" (in French).

- ^ "Mimas". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ "JPL (2009) Cassini Equinox Mission: Mimas". Archived from the original on 6 April 2009. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- ^ Harrison (1908) Prolegomena to the study of Greek religion, ed. 2, p. 514

- ^ Harvey, Samantha (11 April 2007). "NASA: Solar System Exploration: Planets: Saturn: Moons: Mimas: Facts & Figures". NASA. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ^ a b Roatsch, T.; Jaumann, R.; Stephan, K.; Thomas, P. C. (2009). "Cartographic Mapping of the Icy Satellites Using ISS and VIMS Data". Saturn from Cassini-Huygens. pp. 763–781. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6_24. ISBN 978-1-4020-9216-9.

- ^ a b c Jacobson, Robert. A. (1 November 2022). "The Orbits of the Main Saturnian Satellites, the Saturnian System Gravity Field, and the Orientation of Saturn's Pole*". The Astronomical Journal. 164 (5): 199. Bibcode:2022AJ....164..199J. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ac90c9. S2CID 252992162.

- ^ Verbiscer, A.; French, R.; Showalter, M.; Helfenstein, P. (9 February 2007). "Enceladus: Cosmic Graffiti Artist Caught in the Act". Science. 315 (5813): 815. Bibcode:2007Sci...315..815V. doi:10.1126/science.1134681. PMID 17289992. S2CID 21932253. Retrieved 20 December 2011. (supporting online material, table S1)

- ^ Observatorio ARVAL (15 April 2007). "Classic Satellites of the Solar System". Observatorio ARVAL. Archived from the original on 20 September 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- ^ "Herschel". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology Research Program.

- ^ Herschel, W. (1790). "Account of the Discovery of a Sixth and Seventh Satellite of the Planet Saturn; With Remarks on the Construction of Its Ring, Its Atmosphere, Its Rotation on an Axis, and Its Spheroidical Figure". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 80: 11. Bibcode:1790RSPT...80....1H. doi:10.1098/rstl.1790.0001. JSTOR 106823.

- ^ Herschel, William Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Vol. 80, reported by Arago, M. (1871). "Herschel". Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution: 198–223. Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2006.

- ^ As reported by William Lassell, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 42–43 (14 January 1848)

- ^ Lassell, William (1848). "Satellites of Saturn: Observations of Mimas, the closest and most interior Satellite of Saturn". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 8: 42–43. Bibcode:1848MNRAS...8...42L. doi:10.1093/mnras/8.3.42. Retrieved 26 November 2006.

- ^ "Mimas". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020.

"Mimas". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

"Mimas". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d. - ^ "Mimas". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ "Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, Mĭmas". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ "JPL (ca. 2009) Cassini Equinox Mission: Mimas". Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- ^ Paul Schenk (2011), Geology of Mimas?, in 42nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference

- ^ Jane Ellen Harrison (1908) "Orphic Mysteries", in Prolegomena to the study of Greek religion, page 514:

- ^ Elkins-Tanton, Linda E. (2006). Jupiter and Saturn. Infobase Publishing. p. 144. ISBN 9781438107257.

- ^ Moore, Jeffrey M.; Schenk, Paul M.; Bruesch, Lindsey S.; Asphaug, Erik; McKinnon, William B. (October 2004). "Large impact features on middle-sized icy satellites". Icarus. 171 (2): 421–443. Bibcode:2004Icar..171..421M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.05.009. (subscription required)

- ^ Lainey, V; Rambaux, N; Tobie, G; Cooper, N; Zhang, Q; Noyelles, B; Baillié, K (7 February 2024). "A recently formed ocean inside Saturn's moon Mimas". Nature. 626 (7998): 280–282. Bibcode:2024Natur.626..280L. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06975-9. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 38326592. S2CID 267546453.

- ^ Hedman, M.; Burns, J.; Tiscareno, M.; Porco, C.; Jones, G.; Roussos, E.; Krupp, N.; Paranicas, C.; Kempf, S. (3 August 2007). "The Source of Saturn's G Ring". Science. 317 (5838): 653–656. Bibcode:2007Sci...317..653H. doi:10.1126/science.1143964. PMID 17673659. S2CID 137345.

- ^ "IAUC 3660: 1982 BB; Sats OF SATURN; P/SCHWASSMANN-WACHMANN 1".

- ^ Guinness Book of Astronomy, Patrick Moore, Guinness Publishing, second edition, 1983 pp 110, 112

- ^ Tajeddine, R.; Rambaux, N.; Lainey, V.; Charnoz, S.; Richard, A.; Rivoldini, A.; Noyelles, B. (17 October 2014). "Constraints on Mimas' interior from Cassini ISS libration measurements". Science. 346 (6207): 322–324. Bibcode:2014Sci...346..322T. doi:10.1126/science.1255299. PMID 25324382. S2CID 206558386.

- ^ a b Rhoden, A. R.; Henning, W.; Hurford, T. A.; Patthoff, D. A.; Tajeddine, R. (24 February 2017). "The implications of tides on the Mimas ocean hypothesis". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 122 (2): 400–410. Bibcode:2017JGRE..122..400R. doi:10.1002/2016JE005097. S2CID 132214182.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (21 January 2022). "An Ocean May Lurk Inside Saturn's 'Death Star' Moon - New research is converting some skeptics to the idea that tiny, icy Mimas may be full of liquid". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ "SwRI scientist uncovers evidence for an internal ocean in small Saturn moon". Southwest Research Institute (Press release). 19 January 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ Lainey, V.; Rambaux, N.; Tobie, G.; Cooper, N.; Zhang, Q.; Noyelles, B.; Baillié, K. (7 February 2024). "A recently formed ocean inside Saturn's moon Mimas". Nature. 626 (7998): 280–282. Bibcode:2024Natur.626..280L. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06975-9. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 38326592. S2CID 267546453.

- ^ "Pioneer 11 Full Mission Timeline". Dmuller.net. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ^ Young, Kelly (11 February 2005). "Saturn's moon is Death Star's twin". New Scientist. Retrieved 21 August 2008.

Saturn's diminutive moon, Mimas, poses as the Death Star – the planet-destroying space station from the movie Star Wars – in an image recently captured by NASA's Cassini spacecraft.

- ^ Cook, Jia-Rui C. (29 March 2010). "1980s Video Icon Glows on Saturn Moon". NASA. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ^ "Bizarre Temperatures on Mimas". NASA. 29 March 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ^ "Saturn moon looks like Pac-Man in image taken by Nasa spacecraft". The Daily Telegraph. 30 March 2010. Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

External links

[edit]- Cassini mission page – Mimas

- Mimas Profile at NASA's Solar System Exploration site

- The Planetary Society: Mimas

- Google Mimas 3D, interactive map of the moon

- Mimas page at The Nine Planets

- Views of the Solar System – Mimas

- Cassini images of Mimas

- Images of Mimas at JPL's Planetary Photojournal

- 3D shape model of Mimas (requires WebGL)

- Paul Schenk's Mimas blog entry and movie of Mimas's rotation on YouTube

- Mimas global and polar basemaps (June 2012) from Cassini images

- Mimas atlas (July 2010) from Cassini images

- Mimas nomenclature and Mimas map with feature names from the USGS planetary nomenclature page

- Figure "J" is Mimas transiting Saturn in 1979, imaged by Pioneer 11 from here