Meillet's principle

In comparative linguistics, Meillet's principle (/meɪ.ˈjeɪz/ may-YAYZ), also known as the three-witness principle or three-language principle, states that apparent cognates must be attested in at least three different, non-contiguous daughter languages in order to be used in linguistic reconstruction. The principle is named after the French linguist Antoine Meillet.

History

[edit]

In 1903, the French linguist Antoine Meillet published his Introduction à l'étude comparative des langues indo-européennes ('An Introduction to the Comparative Study of Indo-European Languages'). In it, he argued that any etymon purported to be a part of the larger proto-language should only be reconstructed if there are at least three different reflexes in the daughter languages.[1] Meillet viewed typological arguments for the relatedness of languages as extremely weak. He wrote:

Chinese and a language of Sudan or Dahomey such as Ewe [...] may both use short and generally monosyllabic words, make contrastive use of tone, and base their grammar on word order and the use of auxiliary words, but it does not follow from this that Chinese and Ewe are related, since the concrete detail of their forms does not coincide; only coincidence of the material means of expression is probative.[2]

Meillet used this principle to articulate relationships found in grammatical features, morphological features, or suppletive agreement. He believed that the strongest pieces of evidence for affinity were shared "local morphological peculiarities, anomalous forms, and arbitrary associations", which he referred to collectively as "shared aberrancy".[3]

Overview

[edit]Meillet's principle states that cognates – referred to as "witnesses" – must be attested in at least three different daughter languages before the word in the parent language can be reconstructed.[4] The cognates must be non-contiguous; that is, none of the languages being used in the reconstruction may be descended from another language being used.[5] A commonly cited example of suppletive agreement, a kind of shared aberrancy, is found in the copulae used across the Indo-European languages; even though the copulae in each of the individual Indo-European languages are irregular, the irregular forms are cognate with each other across the related language families.[3] Relationships between cognates are often most stable in commonly used terms or expressions and this is also sometimes referred to as Meillet's principle as well since Meillet also identified this trend.[6][7] Although the principle is commonly associated with Meillet, it has also been referred to as the three-witness principle or three-language principle.[8]

Application

[edit]

The use of Meillet's principle to identify linguistic affinity by analyzing grammatical features and shared suppletive agreement is standard practice in historical linguistics.[3] Meillet's principle serves to assist comparative linguists in avoiding the conflation of taxonomic relationships with relationships in language contact or coincidence.[9] The process also avoids the issues associated with phonological typology, since languages with strongly established cognates may not have cognates which are superficially similar phonologically. Examples of this include the word for 'five' in English, French (cinq), Russian (пять pyat'), and Armenian (հինգ hing); although none of these words sound like each other, all of them mean the same thing and are derived from the Proto-Indo-European word *penkʷe meaning 'five' as well.[10]

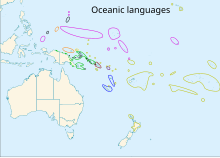

Alexandre François has argued that the principle should also be applied to interpreting the original definition of the reconstructed form.[1] For example, François suggests several definitions for the Proto-Oceanic word *tabu ('off-limits, forbidden, sacred due to fear or awe of spiritual forces') based only on the comparative evidence of semantic relations between other Oceanic languages.[11] Other linguists, such as Lyle Campbell, have supported the principle's utility in identifying strictly linguistic relationships when other evidence, such as archeological or genetic, suggest that groups intermingled.[12]

The original formulation has been subject to some criticism. Scott DeLancey and Henry M. Hoenigswald have both argued that two witnesses may be sufficient if borrowing and linguistic innovation can be ruled out. They argue that if neither of these exceptions apply, the only logical conclusion is that the shared feature must be descended from an earlier common parent language.[13][14] DeLancey, however, admits that while "two witnesses make a case for reconstructing a feature to the proto-language [...] by Meillet's Principle, three witnesses constitute a conclusive case".[15]

See also

[edit]- Classification of the Indigenous languages of the Americas

- Classification of Thracian

- Linguistic typology

- Loanword § Linguistic classification

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b François 2022, p. 32.

- ^ Campbell 1997, p. 232.

- ^ a b c Campbell 1997, p. 217.

- ^

- Campbell 1997, p. 104.

- DeLancey 2023, p. 108.

- Dunkel 1978, p. 14.

- Evans 2005, p. 268.

- Trask 2000, p. 209.

- ^ Dunkel 1978, p. 14.

- ^ Hackstein & Sandell 2023, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Hackstein 2020, pp. 16–17.

- ^

- Dunkel 1978, p. 14.

- Trask 2000, p. 209.

- DeLancey 2023, p. 108.

- ^ François 2022, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Campbell 1997, p. 212.

- ^ François 2022, pp. 32–35.

- ^ Campbell 1997, p. 104.

- ^ DeLancey 2023, p. 108.

- ^ Hoenigswald 1950, pp. 357–358.

- ^ DeLancey 2023, p. 115.

Sources

[edit]- Campbell, Lyle (1997). American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America. New York City: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514050-8.

- DeLancey, Scott (2023). "The antiquity of verb agreement in Trans-Himalayan (Sino-Tibetan)". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 86 (1): 101–119. doi:10.1017/S0041977X23000162. ISSN 0041-977X.

- Dunkel, George (1978). "Preverb Deletion in Indo-European?". Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung. 92 (1/2). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: 14–26. ISSN 0044-3646. JSTOR 40848548.

- Evans, Nicholas (2005). "Australian Languages Reconsidered: A Review of Dixon (2002)". Oceanic Linguistics. 44 (1): 242–286. doi:10.1353/ol.2005.0020. hdl:1885/31199. ISSN 0029-8115.

- François, Alexandre (2022). "Awesome forces and warning signs: Charting the semantic history of *tabu words in Vanuatu". Oceanic Linguistics. 61 (1): 212–255. doi:10.1353/ol.2022.0017. ISSN 0029-8115.

- Hackstein, Olav [in German] (2020). "The System of Negation in Albanian: Synchronic Constraints and Diachronic Explanations". In Demiraj, Bardhyl (ed.). Altalbanische Schriftkultur. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 13–32. ISBN 978-3-447-19975-9.

- Hackstein, Olav [in German]; Sandell, Ryan (26 January 2023). "The rise of colligations: English can't stand and German nicht ausstehen können". International Journal of Corpus Linguistics. 28 (1): 60–90. doi:10.1075/ijcl.20022.hac. ISSN 1384-6655.

- Hoenigswald, Henry M. (1950). "The Principal Step in Comparative Grammar". Language. 26 (3). Linguistic Society of America: 357–364. doi:10.2307/409730. ISSN 0097-8507. JSTOR 409730.

- Trask, R. L. (2000). Dictionary of Historical and Comparative Linguistics. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-4744-7331-6. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctvxcrt50.