Marchois (dialect)

| Marchois | |

|---|---|

| Marchés | |

Marchois speaking area | |

| Native to | France |

| Region | La Marche, Communities in Limousin |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAA-gk |

| |

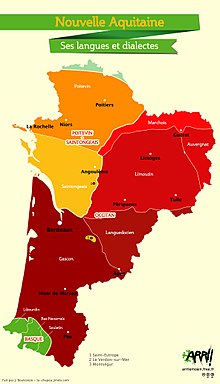

Marchois (French pronunciation: [maʁʃwa]) or Marchese (marchés in Occitan) is a transitional Occitan dialect between the Occitan language and the Oïl languages[1] spoken in the historical region of La Marche, in northern Limousin and its region. Occitan and Oïl dialects meet there.[2][3]

It covers the north-western borders of the Massif Central and forms the western part of the dialects of the Croissant which goes from Charente limousine to Montluçon.

Classification

[edit]

An occitan/oïl transitional dialect

[edit]Marchois is a transitional dialect between the Occitan language and the langues d'oïl.[4][5][6]

It forms the western two-third of the Croissant region where the languages oscillate between the Occitan language in the south and the Oïl languages in the north.[7][8]

Occitan traits

[edit]Concerning Occitan traits, they are closer to Limousin than Auvergnat, both North Occitan dialects. It is sometimes classified as a sub-dialect of Limousin characterized by its transition with French.[9]

It is more regularly mentioned as a full-fledged Occitan dialect,[10][11][12] due to the difficulties of mutual intercomprehension between the people of Limousin and southern La Marche,[13][14][15] and the many features that make it closer to the oïl languages.[16][17][18] In transition with the langues d'oïl, Marchois is also in transition between the Occitan dialects of Limousin and Auvergne, respectively to the west and to the east of the latter.[19][20]

It is sometimes considered a language in its own right, because of its intermediate position between Occitan language and Oïl languages, the same way as the Franco-Provençal language.[21][22][23]

The neighboring dialects of Oïl languages like Poitevin-Saintongeais have features in common with Marchois, which has interactions with the latter,[24] and shares an important common substrate.[25]

Distribution area

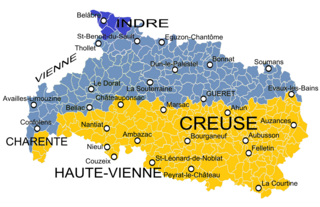

[edit]The area where Marchois is spoken does not coincide with the historical province of La Marche but extends beyond it.[26][27] Marchois is spoken in the north of Creuse,[28][29][30][31] and Haute-Vienne to which must be added the north of Charente Limousine around Confolens, some southern communes of Poitou[32] but also the south of Boischaut, at the southern tip of Berry in the southern parts of Indre[33] and Cher (Saint-Benoît-du-Sault,[34] Lourdoueix-Saint-Michel,[35][36] Culan), and finally Montluçon and its region in the Allier (Châtaigneraie).[37][38][39]

The rest of the department of Allier once out of the Cher valley and from the center of the Bocage bourbonnais forms the eastern part of the Croissant where the speech is Arverno-Bourbonnais (Bocage, Limagne and Bourbonnaise mountain, Vichy). Guéret and Montluçon are the two main towns in La Marche region, both radiating over half of the Creuse department.[40]

Internal varieties

[edit]The Marchois dialect is divided into three main varieties.[41]

- Southern Marchois which extends from the region of Bellac to Combrailles via Le Dorat, Magnac-Laval, Guéret.

- Central Marchois which extends from Availles-Limouzine to Néris-les-Bains via Arnac-la-Poste, La Souterraine then to Montluçon.

- Northern Marchois from Dun-le-Palestel to the south of the Tronçais forest via Bonnat, Châtelus-Malvaleix, Boussac, Treignat then the municipalities located north of Montluçon with the “Biachets” dialect (from Occitan biachés) .

Written forms

[edit]Three main writing systems can be used to write Marchois.[42] All three are encouraged by the research group on the dialects of the Croissant (CNRS):

- The international phonetic alphabet makes it possible to transcribe the language as well to record pronunciations.

- The French spelling can also be used and allows speakers to transcribe their dialects with the writing system of the French language with which they are also all familiar. Marchois being an intermediate dialect with the language of oïl it can therefore also be applied, especially since this spelling emphasises those pronunciations which are specific to it.

- The classic Occitan spelling with a precise local adaptation for Marchois.[43] In Marchois the final Occitan “a” does not exist, it is replaced by a silent “e” as in French (e.g. jornade ("day") in place of the form jornada found in other Occitan dialects). This specific codification of this dialect is recommended by the Institute of Occitan Studies and its local sections (IEO Lemosin, IEO Marcha-Combralha).

History

[edit]Early francization

The vast county of Marche experienced earlier francization than the rest of the Occitan-speaking countries. From the thirteenth century, an aristocratic class speaking langues d'oïl, e.g. the Lusignans, settled locally in the midst of an endogenous Occitanophone nobility. The region of Montluçon became linked in this period to the seigneury of Bourbon and to a territory whose lords were very close to the kings of France. They also originated in Champagne and brought—as was the case in Poitou and Saintonge—settlers from Champagne who spoke the local langue d'oïl variety. These settlers exerted a notable influence on the Bourbonnais d'Oïl but also on the Occitan dialects of Marche and Arverno-Bourbonnais.

The Bourbons arrived thereafter in the rest of the Marche (e.g., the famous count Jacques de La Marche) and influenced even more the language of the nobles. Neighboring Berry (strongly francized, even if significant parts of Occitan still remain) also influenced from the end of the Middle Ages on the towns and villages of the north of La Marche as in the region of Boussac.

The masons of La Creuse

The masons of La Creuse originating in the northern half of this department use Marchois even when displaced to other regions. They play on influences if they do not wish to be understood in certain "foreign" regions: they sometimes use the Occitan features so as not to make themselves understood in a territory where French is spoken, as in Paris, or vice versa, in other Occitan-speaking regions, they rely on langue d'oïl traits.

Distinctive features

[edit]Marchois is linked to Limousin (dialect) (north-Occitan) but also to its northern neighbors, the southern dialects of oïl (Poitevin-Saintongeais, berrichon, bourbonnais d'oïl).[44] The distinctive features of the rest of the Occitan dialects were in part established by Maximilien Guérin[45] or Jean-Pierre Baldit, founder of the Institut d'études occitanes section La Marche and Combrailles.

Distinctive features vis-à-vis other Occitan dialects

- The phonology is close to French: "chabra" is pronounced "chabre" and no longer "chabro".

- Retention of the personal pronoun in front of each verb: "I chante" instead of "chante" or "chanti", as in North Occitan.

- The use as in French of the silent "e" while all other Occitan dialects, including Arverno-Bourbonnais, maintain the final Latin "a" in the feminine.

Distinctive features of Arverno-Bourbonnais

- General preservation of the intervocalic "d" which is lost in Arverno-Bourbonnais: chantada in Marchois (“sang” - pronounced chantade) and chantaa in Arverno-Bourbonnais.

- Maintaining the determiner and its elision in front of a verb that partially disappears in Arverno-Bourbonnais: Qu'es finite in Marchois ("It is finished" - pronounced "kou'i finite") and u'es chabat in Arverno-Bourbonnais (pronounced "é chaba", which is similar to the Franco-Provençal ou est “c'est”).

Occitan traits nevertheless remain very strong in La Marche, which remains attached to Occitan.

Texts

[edit]- Nadau, collected by Marcel Rémy, a Christmas carol from La Souterraine. Transcription in classical Marchois script:

A l'ore de las legendas, quand le clhocher sone mineut, rendam nos dins las eglesias, per i passar le moment pieus.

Vos, las fennas que siatz prias, mesme quos qui que cresan pas. Anatz remplir las eglesias. Las eglesias seran plenas. E tos los cuers sauran chantar, e mesme en plhurant, esperar... Las prieras par le païs, par los absents, par los amics, s'envoleran au Paradis; le petiot Jesus sau escotar; On sau veire le Nadau de guèrre, las misèras, la paubre tèrre.

O sau tot veire e pardonar, Oc-es, raluman nostres amas, a l'ore de las legendas, a l'ore de las prieras.

Authors

[edit]This is a non-exhaustive list of Marchois authors:

- Paul-Louis Grenier, historian and poet from Chambon-sur-Voueize, wrote both in Marchois and Limousin .

- Maximilien Guérin (CNRS), a linguist and also a writer, wrote Mes mille premiers mots en bas-marchois (2020) with Michel Dupeux.[46]

- Marie-Rose Guérin-Martinet has notably published Le Pitit Prince, a translation of The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry into Marchois (2020).[47][48]

- Jean-Michel Monnet-Quelet.

Sample text

[edit]Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Marchois.

- Classic Marchois standard:

Totes las persones naissan lieures e egales en dignitat e en dret. Als son dotades de rason e de consciénçe més i leur fau agir entre als dins une aime de frairesse.

- French standard:

Toutes las persones naissant lieures et égales en dignitat et en dret. Als sont dotades de rason et de conscience mais i leur faut agir entre als dins une aime de frairesse.

References

[edit]- ^ Guérin, Maximilien (2017). " Le marchois : Une langue entre oc et oïl ", Séminaire de l'équipe Linguistique du FoReLL (EA 3816). Poitiers: University of Poitiers.

- ^ Brun-Trigaud, Guylaine (1992). "" Les enquêtes dialectologiques sur les parlers du Croissant : corpus et témoins ", Langue française, vol. 93, no 1". Langue Française. 93 (1): 23–52. doi:10.3406/lfr.1992.5809.

- ^ Brun-Trigaud, Guylaine (2010). " Les parlers marchois : un carrefour linguistique ", Patois et chansons de nos grands-pères marchois. Haute-Vienne, Creuse, Pays de Montluçon (dir. Jeanine Berducat, Christophe Matho, Guylaine Brun-Trigaud, Jean-Pierre Baldit, Gérard Guillaume). Paris: Éditions CPE. ISBN 9782845038271.

- ^ Caubet, Dominique; Chaker, Salem; Sibille, Jean (2002). « Le marchois : problèmes de norme aux confins occitans », Codification des langues de France. Actes du colloque Les langues de France et leur codification organisé par l'Institut national des langues et civilisations orientales (Inalco, Paris, Mai 2000). Paris: L'Harmattan. pp. 63–76. ISBN 2-7475-3124-4.

- ^ Baldit, Jean-Pierre (1982). Les parlers creusois. Guéret: Institut d'Estudis Occitans.

- ^ Brun-Trigaud, Guylaine (1990). Le Croissant: le concept et le mot. Contribution à l'histoire de la dialectologie française au XIXe siècle [thèse], coll. Série dialectologie. Lyon: Centre d’Études Linguistiques Jacques Goudet.

- ^ Guérin, Maximilien (2019). "" Le parler marchois : une particularité du patrimoine linguistique régional ", D'onte Ses". D'Onte Ses. Limoges: Cercle de généalogie et d'histoire des Marchois et Limousins.

- ^ Guérin, Maximilien (2017). " Les parlers du Croissant : une aire de contact entre oc et oïl ", XIIe Congrès de l'Association internationale d'études occitanes. Albi.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Grenier, Paul-Louis (2013). "" Abrégé de grammaire limousine (bas-limousin, haut-limousin, marchois) "". Lemouzi. 208. Limoges.

- ^ Pasty, Gilbert (1999). Glossaire des dialectes marchois et haut limousin de la Creuse. Châteauneuf-sur-Loire. p. 253. ISBN 2-9513615-0-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Vignaud, Jean-François (2016). Atlas de la Creuse-Le Creusois (PDF). Limousin: Institut d'Estudis Occitans. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-09-10. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- ^ "La Marche, apsects lingusitiques; Le Croissant marchois, domaine linguistique".

- ^ Cavaillé, Jean-Pierre (2013). "" " Qu'es chabat ". Une expérience de la disparition entre présence et rémanence. Situation de l'occitan dans le nord limousin : " Qu'es chabat ". An Experience of Disappearance Between Presence and Remanence: Situation of Occitan in the North Limousin ", Lengas - revue de sociolinguistique". Lengas. Revue de Sociolinguistique (73). Montpellier: Presses universitaires de la Méditerranée (Paul Valéry University Montpellier 3). doi:10.4000/lengas.99.

- ^ "En Lemosin: La croix et la bannière" (in French and Occitan). « Nous avons suivi la procion en 2014, guidés par de vieux habitués, qui nous ont fait partager, en occitan limousin et en marchois (car Magnac se trouve tout au nord de l'aire culturelle occitane), leur longue expérience de dévotion et d’observation participante. ». 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "L'occitan a sa plaça a la Bfm dempuei sa dubertura : La langue limousine présente depuis l'origine de la Bfm" (PDF). Vivre à Limoges (revue officielle de la ville de Limoges) (in Occitan and French). Vol. 142. October 2019.

- ^ Barbier, Laurène (2019). "« Le parler de Genouillac. Les particularités d'un patois dit « francisé » et ses enjeux descriptifs », 2èmes rencontres sur les parlers du Croissant 15-16 mars 2019 Montluçon" (PDF). Montluçon.

- ^ "Le marchois, un patois encore utilisé au quotidien dans la Creuse". LCI. 2018.

- ^ Christophe, Marianne (2012). Le fonds de l'IEO Lemosin. Aménagement de la bibliothèque d'une association (PDF). Limoges: University of Limoges.

- ^ Von Wartburg, Walther; Keller, Hans-Erich; Geuljans, Robert (1969). Bibliographie des dictionnaires patois galloromans. Geneva: Librairie Droz. p. 376. ISBN 978-2-600-02807-3.

- ^ Goudot, Pierre (2004). Microtoponymie rurale et histoire locale : dans une zone de contact français-occitan, la Combraille : les noms de parcelles au sud de Montluçon (Allier). Montluçon: Cercle archéologique de Montluçon, coll. « études archéologiques ». p. 488. ISBN 978-2-915233-01-8.

- ^ Martho, Christophe (2010). " Préface ", Patois et chansons de nos grands-pères marchois (Haute-Vienne, Creuse, pays de Montluçon). Paris. ISBN 9782845038271.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Monnet-Quelet, Jean-Michel (2013). Le Croissant marchois entre oc et oïl (Charente, Vienne, Indre, Haute-Vienne, Creuse, Cher, Allier, Puy-de-Dôme). Cressé: Editions des Régionalismes. p. 216. ISBN 978-2-8240-0146-3.

- ^ Monnet-Quelet, Jean-Michel (2017). Glossaire marchois des animaux ailés : insectes, oiseaux, gallinacés et autres volailles de basse-cou. Cressé: Editions des Régionalismes. p. 183. ISBN 978-2-8240-0798-4.

- ^ Boula de Mareüil, Philippe; Adda, Giles. Comparaison de dialectes du Croissant avec d'autres parlers d'oïl (berrichon, bourbonnais et poitevin-saintongeais) et d'oc (PDF). Laboratoire d'informatique pour la mécanique et les sciences de l'ingénieur.

- ^ Dussauchaud, Olivier (2017). Synthèse sur l'étude de la part d'occitan limousin en poitevin-saintongeais (mémoire en langue occitane) (PDF). Toulouse: University of Toulouse-Jean Jaurès.

- ^ The Linguasphere Register : The indo-european phylosector (PDF). Linguasphere Observatory. 1999–2000. p. 402.

- ^ Quint, Nicolas (1997). " Aperçu d'un parler de frontière : le marchois ", Jeunes chercheurs en domaine occitan. Montpellier: Presses universitaires de la Méditerranée (Uninversité Paul-Valéry). pp. 126–135.

- ^ Quint, Nicolas (1996). "" Grammaire du parler occitan nord-limousin marchois de Gartempe et de Saint-Sylvain-Montaigut (Creuse) : Étude phonétique, morphologique et lexicale ", La Clau Lemosina". La Clau Lemosina. Limoges: Institut d'Estudis Occitans. ISSN 0339-6487.

- ^ Quint, Nicolas (1991). "" Le parler marchois de Saint-Priest-la-Feuille (Creuse) ", La Clau Lemosina". La Clau Lemosina. Limoges: Institut d'Estudis Occitans. ISSN 0339-6487.

- ^ Pasty, Gilbert (1999). Glossaire des dialectes marchois et haut limousin de la Creuse. Châteauneuf-sur-Loire: G.Pasty. p. 253. ISBN 2-9513615-0-5.

- ^ Brun-Trigaud, Guylaine (2016). " Les formes de parlers marchois en Creuse ", Le Croissant linguistique et le Parler marchois (3ème Colloque).

- ^ Sumien, Domergue (2014). En explorant lo limit lingüistic, Jornalet (in Occitan). Toulouse, Barcelona: Associacion entara Difusion d'Occitània en Catalonha (ADÒC). ISSN 2385-4510.

- ^ "Sur le parler marchois et le croissant linguistique". La Montagne. Clermont-Ferrand: La Montagne, Groupe Centre France. 2019. ISSN 2109-1560.

- ^ Lavalade, Yves (2019). "Journée d'échanges sur la Marche occitan". La Nouvelle République. Tours, Châteauroux: La Nouvelle République du Centre-Ouest. ISSN 2260-6858.

- ^ Aubrun, Michel (1983). "La terre et les hommes d'une paroisse marchoise. Essai d'histoire régressive". Études Rurales. 89. Études rurales, École des hautes études en sciences sociales: 247–257. doi:10.3406/rural.1983.2918. ISSN 0014-2182.

- ^ Aubrun, Michel (2018). Lourdoueix-Saint-Michel : études historiques sur une paroisse marchoise et ses environs. p. 147.

- ^ Berducat, Jeanine; Matho, Christophe; Brun-Trigaud, Guylaine; Baldit, Jean-Pierre; Guillaume, Gérard (2010). Patois et chansons de nos grands-pères marchois : Haute-Vienne, Creuse, Pays de Montluçon (in French and Occitan). Paris: Éditions CPE. p. 160. ISBN 978-2-84503-827-1.

- ^ Linguasphere register: Le marchois est enregistré sous le numéro 51-AAA-gk et comprend deux sous dialectes : le marchois creusois (51-AAA-gkb - Cruesés) et le marchois montluçonnais (51-AAA-gkc - Montleçonés).

- ^ Roux, Patrick (2014). Guide de survie en milieu occitan (in French and Occitan). Rodez: Estivada. pp. 8–9.

- ^ Monnet-Quelet, Jean-Michel (2019). "Entre oïl et oc, la perception du Croissant marchois. Charente -Vienne -Indre -Haute Vienne -Creuse -Cher -Allier -Puy de Dôme". Études marchoise.

- ^ Baldit, Jean-Pierre (2010). Les parlers de la Marche. Extension et caractéristiques », Patois et chansons de nos grands-pères marchois. Haute-Vienne, Creuse, Pays de Montluçon (dir. Jeanine Berducat, Christophe Matho, Guylaine Brun-Trigaud, Jean-Pierre Baldit, Gérard Guillaume). Paris: Éditions CPE. pp. 22–35. ISBN 9782845038271.

- ^ Guérin, Maximilien; Dupeux, Michel (2020). "Comment écrire le bas-marchois ?". Mefia te ! Le journal de la Basse-Marche. 5. Archived from the original on 2021-05-18. Retrieved 2021-04-29.

- ^ Baldit, Jean-Pierre (2010). " Quelle graphie utilisée pour le marchois ? ", Patois et chansons de nos grands-pères marchois. Haute-Vienne, Creuse, Pays de Montluçon (dir. Jeanine Berducat, Christophe Matho, Guylaine Brun-Trigaud, Jean-Pierre Baldit, Gérard Guillaume). Paris: Éditions CPE. pp. 84–87. ISBN 9782845038271.

- ^ Baldit, Jean-Pierre (2010). " Les parlers de la Marche. Extension et caractéristiques. Caractéristiques oïliques ", Patois et chansons de nos grands-pères marchois. Haute-Vienne, Creuse, Pays de Montluçon (dir. Jeanine Berducat, Christophe Matho, Guylaine Brun-Trigaud, Jean-Pierre Baldit, Gérard Guillaume). Paris: Éditions CPE. pp. 28–29. ISBN 9782845038271.

- ^ Guérin, Maximilien (2017). Description du parler marchois de Dompierre-les-Églises : phonologie, conjugaison et lexique (communication). Le Dorat: 1ères Rencontres sur les parlers du Croissant.

- ^ Guérin, Maximilien; Dupeux, Michel (2020). Mes mille premiers mots en bas-marchois. Edition Tintenfaß & La Geste Éditions. ISBN 979-1-03-530735-6.

- ^ "Petit Prince collection : « Les deux dialectes du Croissant sont représentés : le marchois par Marie-Rose Guérin-Martinet et l'arverno-bourbonnais par Henri Grosbost".

- ^ Es pareguda una nòva version del Pichon Prince en parlar del Creissent : Entitolat Le Pitit Prince, es estat traduch dins lo parlar de Furçac per Marie-Rose Guérin-Martinet (in Occitan). Toulouse, Barcelona: Association de Diffusion Occitane en Catalogne (ADÒC), Jornalet. 2020. ISSN 2385-4510.

External links

[edit]- Authority control:

- https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb169289936 : Bibliothèque nationale de France

- Notices related to university research:

- IdRef [Marchois (dialecte)]

- Notices related to local studies:

- Société des Sciences de la Creuse; Amis de Montluçon - Ouvrages de références

- Linguistic authority notcies:

- Observatoire Linguistique, Colloque parlers du Croissant, Maximilien Guérin (Université de Poitiers)