List of King Crimson members

King Crimson were an English progressive rock band from London. Formed in November 1968 (officially January 1969), the group originally included bassist and vocalist Greg Lake, guitarist and later keyboardist Robert Fripp, keyboardist and woodwind musician Ian McDonald, lyricist Peter Sinfield, and drummer Michael Giles. After a number of personnel changes, the group disbanded in 1974 but have since reformed on a number of occasions. As of the latest lineup change in 2020, King Crimson consisted of Fripp (the sole constant member of the band), saxophonist and flautist Mel Collins (who first joined in 1970), bassist Tony Levin (who first joined in 1981), drummers Pat Mastelotto (who first joined in 1994) and Gavin Harrison (since 2007), guitarist and vocalist Jakko Jakszyk (since 2013), and drummer and keyboardist Jeremy Stacey (since 2016).

History

[edit]1969–1974

[edit]After some initial rehearsals starting in late November 1968, King Crimson were officially formed on 13 January 1969 with a lineup of Greg Lake on bass and vocals, Robert Fripp on guitar, Ian McDonald on woodwind and keyboards, Michael Giles on drums, and Peter Sinfield as the band's lyricist and operator of the band's light shows on stage (Sinfield later expanded his role to also playing synthesizer).[1] After the recording of the band's debut album In the Court of the Crimson King, McDonald and Giles left King Crimson in January 1970 after playing their last show on 16 December 1969.[2]

Fripp, Lake and Sinfield began recording the band's second album In the Wake of Poseidon, with the sessions also featuring Giles and his brother Peter Giles on drums and bass respectively, as well as saxophonist Mel Collins. Lake then departed to form Emerson, Lake & Palmer,[3][4] while Fripp and Sinfield rebuilt the group with Collins, Gordon Haskell and Andy McCulloch in place of McDonald, Lake and Giles, respectively.[1] After recording Lizard, both Haskell and McCulloch departed.[5]

Ian Wallace replaced McCulloch in December 1970,[1] and Raymond "Boz" Burrell took over from Haskell the following February. The group released Islands and returned to regular touring over the next year, Burrell, Collins and Wallace all left to join Alexis Korner's new group Snape in April 1972.[6] Sinfield had left the group in January 1972.

After the release of the live album Earthbound, Fripp rebuilt King Crimson again in July 1972 with the additions of former Family bassist and vocalist John Wetton, violinist and keyboardist David Cross, former Yes drummer Bill Bruford, and percussionist Jamie Muir.[1][7] After the first of two live shows scheduled upon completion of the group's new album Larks' Tongues in Aspic, Muir abruptly left King Crimson to pursue Buddhism.[8] The remaining four-piece issued Starless and Bible Black in March 1974.[9]

By the time the group began recording the follow-up Red in July 1974, King Crimson were a trio following Cross's departure at the end of the previous tour.[10] Later, on 25 September, Fripp announced that King Crimson had officially disbanded,[1] claiming that the group were "completely over for ever and ever".[11]

1981–2008

[edit]After several years of side projects, Fripp formed a group called Discipline in April 1981 with former King Crimson drummer Bruford, as well as vocalist and guitarist Adrian Belew, and bassist and Chapman stick player Tony Levin. By the time the band's debut album Discipline was released in October, they had adopted the King Crimson name.[12] This lineup remained stable for three years, releasing follow-up albums Beat and Three of a Perfect Pair, before disbanding again upon the conclusion of a promotional touring cycle in July 1984.[13]

After a ten-year break, King Crimson reformed again in 1994, with Fripp, Belew, Levin and Bruford joined by second bassist/Chapman stick player Trey Gunn and second drummer Pat Mastelotto.[1] This lineup, dubbed the "Double Trio", began rehearsing in April 1994 and released its only studio effort THRAK the following year.[14] After touring extensively, the group returned to the studio in May 1997 for the recording of their twelfth studio album, but faced difficulties making progress with the sessions.[15] Instead of disbanding again, Fripp decided to initiate a process of "fraKctalisation", splitting the six band members into four "ProjeKcts" of various lineups.[16] Each ProjeKct performed several live shows and wrote together, serving as "research and development" units for the full King Crimson incarnation.[15]

The ProjeKcts spawned several studio and live recordings, which were issued in 1999 as part of The ProjeKcts box set.[17] By this time the lineup of King Crimson was a "Double Duo" consisting of Belew, Fripp, Gunn and Mastelotto, following the departures of Bruford and Levin.[1] The band released two new studio albums, The ConstruKction of Light and The Power to Believe, before Gunn announced in November 2003 that he was leaving to explore new musical opportunities.[18] Levin returned to take his place.[1] Rehearsals subsequently began for planned new material, with a string of rehearsal sessions taking place in September 2004,[19] before the group was placed "on hold" once again.[1]

In June 2007, Fripp announced that a new lineup of King Crimson had been finalised for the band's 40th anniversary tour the following year.[20] In addition to the members of the 2004 incarnation, Gavin Harrison of Porcupine Tree was added as a second drummer.[21] The tour took place in August 2008,[22] after which members returned to focus on other projects.[1]

In December 2010, Fripp wrote that the King Crimson "switch" had been set to "off" since October 2008, citing several reasons for this decision.[23] This was followed by Fripp's announcement of his retirement from the music industry in August 2012.[24]

2013 onwards

[edit]In September 2013, despite claiming the previous year that he was retiring, Fripp announced another reformation of King Crimson.[25] In addition to Levin, Mastoletto and Harrison, the eighth lineup was confirmed to include returning saxophonist and flautist Mel Collins, new guitarist and vocalist Jakko Jakszyk, and third drummer Bill Rieflin.[26] In March 2016, Jeremy Stacey replaced Rieflin for the year's touring,[27] becoming a full member during the winter leg of the tour.[28] Rieflin switched over to being the band's first full-time keyboardist upon his return in January 2017.[29]

Rieflin was temporarily replaced again for an autumn 2017 tour by Chris Gibson.[30] For the band's 50th anniversary tour in 2019, it was announced that Rieflin would once more be temporarily replaced, this time by Theo Travis.[31] However, after a day of rehearsal, the band opted instead to do the 2019 tour as a seven-piece.[32] Rieflin's parts were divided among other band members, with Jakszyk and Collins adding keyboards to their on-stage rigs, and Levin once again using the synthesizer he used during the 1980s tours.[33] Rieflin died of cancer on March 23, 2020, reducing the line-up to a septet.[34]

On December 8, 2021, the band played the last show of their "Music Is Our Friend" tour, after which Fripp tweeted out that the band had "Moved from sound to silence",[35] Levin published in his blog “Tonight is the final concert of the tour, and quite possibly the final King Crimson concert.".[35] No announcements have been heard from the band since December, though Harrison has said that he in unsure whether the band is over.[36] The band was not musically active in 2022, with Fripp re-stating that the band is unlikely to tour again.[37]

Members

[edit]- Note: Release contributions do not include albums issued as part of the King Crimson Collector's Club, or other limited releases.

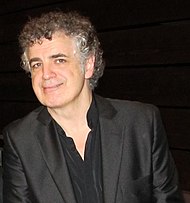

| Image | Name | Years active | Instruments | Release contributions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robert Fripp |

|

|

all King Crimson releases | |

| Peter Sinfield | 1968–1972 (died 2024) |

|

| |

| Michael Giles | 1968–1970 |

|

| |

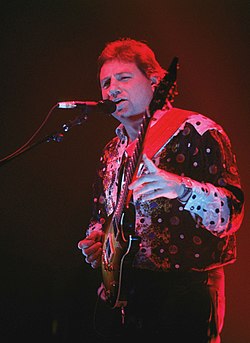

| Greg Lake | 1968–1970 (died 2016) |

| ||

| Ian McDonald | 1968–1970 (session contributor in 1974) (died 2022) |

|

| |

| Mel Collins |

|

|

| |

| Peter Giles | 1970 | bass | In the Wake of Poseidon (1970) | |

| Gordon Haskell | 1970 (session contributor earlier in 1970) (died 2020) |

|

||

| Andy McCulloch | 1970 | drums |

| |

| Ian Wallace | 1970–1972 (died 2007) |

|

| |

| Raymond "Boz" Burrell | 1971–1972 (died 2006) |

| ||

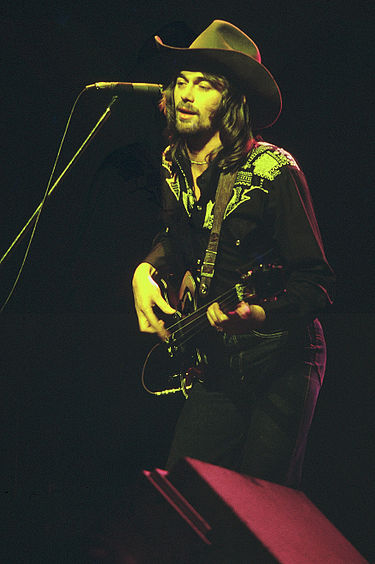

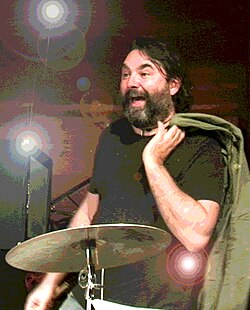

| Bill Bruford |

|

|

| |

| John Wetton | 1972–1974 (died 2017) |

|

| |

| David Cross | 1972–1974 |

| ||

| Jamie Muir | 1972–1973 |

|

Larks' Tongues in Aspic (1973) | |

| Adrian Belew |

|

|

| |

| Tony Levin |

|

|

| |

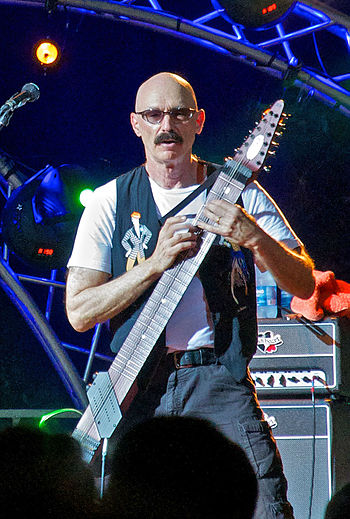

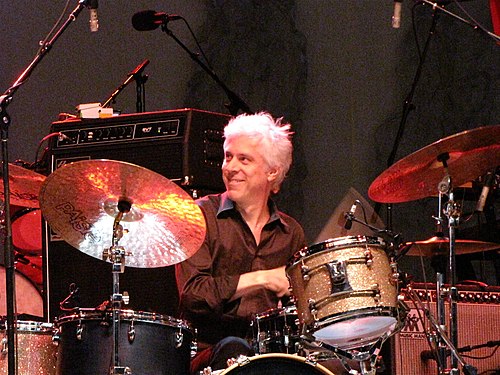

| Pat Mastelotto |

|

|

| |

| Trey Gunn | 1994–2003 |

|

| |

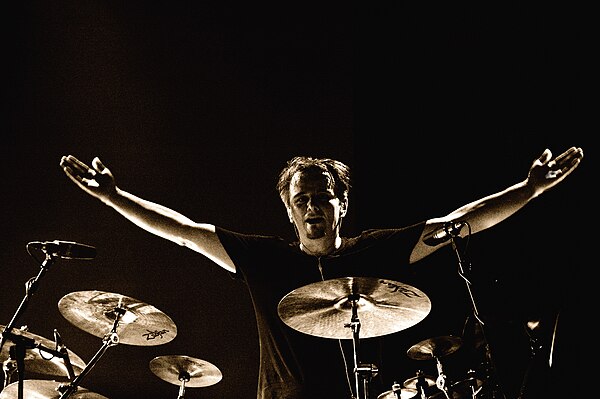

| Gavin Harrison |

|

|

all releases from Live at the Orpheum (2015) onwards | |

| Jakko Jakszyk | 2013–2021 |

|

all releases from Live at the Orpheum (2015) onwards | |

| Bill Rieflin |

|

|

| |

| Jeremy Stacey | 2016–2021 |

|

all releases from Heroes (2017) onwards |

Touring musicians

[edit]| Image | Name | Years active | Instruments | Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chris Gibson | 2017 |

|

Gibson temporarily replaced Bill Rieflin during an autumn 2017 concert tour.[30] He appears on the second half of the 2017 disc of Audio Diary 2014-2018. |

Session contributors

[edit]| Image | Name | Years active | Instruments | Release contributions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keith Tippett | 1970–1971 (died 2020) | piano |

| |

| Mark Charig |

|

cornet |

| |

| Robin Miller |

| |||

| Nick Evans | 1970 |

|

Lizard (1970) | |

| Jon Anderson |

| |||

| Paulina Lucas | 1971 | Islands (1971) | ||

| Wilf Gibson | 1971 (died 2014) |

| ||

| Harry Miller | 1971 (died 1983) |

| ||

| Richard Palmer-James | 1973–1974 |

|

| |

| Eddie Jobson | 1975 |

|

USA (1975) (studio overdubs only) |

Timeline

[edit]

Line-ups

[edit]King Crimson

[edit]| Period | Members | Releases |

|---|---|---|

| November 1968 – January 1970 |

|

|

| January – April 1970 |

|

|

| August – November 1970 |

|

|

| February – December 1971 |

|

|

| December 1971 – April 1972 |

|

|

| July 1972 – February 1973 |

|

|

| February 1973 – July 1974 |

|

|

| July – September 1974 |

|

|

| Band inactive September 1974 – April 1981 | ||

| April 1981 – July 1984 |

|

|

| Band inactive July 1984 – April 1994 | ||

| April 1994 – December 1999 (The Double Trio) |

|

|

| December 1999 – December 2003 (The Double Duo) |

|

|

| December 2003 – June 2007 |

|

|

| June 2007 – August 2008 |

|

|

| Band inactive August 2008 – September 2013 | ||

| September 2013 – March 2016 |

|

|

| March 2016 – January 2017 |

|

|

| January 2017 – April 2019 |

|

|

| April 2019 – December 2021 |

|

|

Spin-off bands

[edit]| Period | Members | Releases |

|---|---|---|

| ProjeKct One (December 1997) |

|

|

| ProjeKct Two (November 1997 – July 1998) |

|

|

| ProjeKct Three (March 1999 and March 2003) |

|

|

| ProjeKct Four (October – November 1998) |

|

|

| ProjeKct X (December 1999 – May 2000) |

|

|

| 21st Century Schizoid Band (2002–2004) |

|

|

| ProjeKct Six (October 2006) |

|

none – Collector's Club releases only |

| Jakszyk, Fripp and Collins: A King Crimson ProjeKct (2010–2011) |

|

|

| The Crimson ProjeKct (2011–2014) |

|

|

| Beat (September - November 2024) |

|

|

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Eder, Bruce. "King Crimson: Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Fripp, Robert (7 November 2016). "King Crimson 1969: A Personal Throughview from the Guitarist". Discipline Global Mobile. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Fuller, Graham (28 September 2009). "Why King Crimson are still prog-rock royalty". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Smith 2019, pp. 77–78

- ^ Lynch, Dave. "Lizard - King Crimson: Songs, Reviews, Credits". AllMusic. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Smith, Sid (9 June 2018). "46 Years Ago Today". Discipline Global Mobile. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Fripp, Robert (31 August 1999). "Robert Fripp's Diary: World Central Held A Mass". Discipline Global Mobile. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Singleton, David (3 November 2016). "Larks Tongues in Aspic - The Long View". Discipline Global Mobile. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Eder, Bruce. "Starless and Bible Black - King Crimson: Songs, Reviews, Credits". AllMusic. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ DeRiso, Nick (6 October 2015). "Revisiting King Crimson's Implosion on 'Red'". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Hughes, Rob (31 October 2014). "Robert Fripp, interview: 'I'm a very difficult person to work with'". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Singleton, David (3 November 2016). "Discipline - The Long View". Discipline Global Mobile. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Smith, Sid (14 March 2019). "A Perfect Trio". Discipline Global Mobile. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Fripp, Robert (23 March 2012). "Robert Fripp's Diary: DGM HQ: A Sunny Day". Discipline Global Mobile. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ a b Planer, Lindsay. "Nashville Rehearsals - King Crimson: Songs, Reviews, Credits". AllMusic. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ "Nashville Rehearsals". Discipline Global Mobile. 10 October 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Hayes, Kelvin. "The ProjeKcts - King Crimson: Songs, Reviews, Credits". AllMusic. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Gunn, Trey (21 November 2003). "An Amazing Journey". Trey Gunn. Archived from the original on 2 April 2004. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ "Sept 1, 2004: Ex Uno Plures". Discipline Global Mobile. 11 June 2008. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Smith, Sid (28 June 2007). "King Crimson Confirmed For 40th Anniversary Celebrations". Discipline Global Mobile. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Smith, Sid (19 November 2007). "The Return of King Crimson". Discipline Global Mobile. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Kelman, John (4 September 2008). "King Crimson: King Crimson: Park West, Chicago, Illinois August 7, 2008". All About Jazz. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Fripp, Robert (5 Dec 2010). "Robert Fripp's Diary: Marriot Downtown, 85, West Street, NYC". dgmlive.com. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 7 Mar 2021.

- ^ Coplan, Chris (26 September 2013). "King Crimson announce reunion for 2014". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on 25 September 2021. Retrieved 7 Mar 2021.

- ^ Giles, Jeff (25 September 2013). "Robert Fripp Resurrects King Crimson". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ "King Crimson unveil new-line up and 2014 tour plans". Uncut. 25 September 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Munro, Scott (7 March 2016). "King Crimson call up drummer Jeremy Stacey". Prog. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Fripp, Robert (3 January 2017). "Robert Fripp's Diary: Bredonborough". Discipline Global Mobile. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ Lifton, Dave (7 January 2017). "King Crimson Will Tour The U.S. In 2017". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ a b Smith, Sid (13 October 2017). "Chris Gibson joins Crim". Discipline Global Mobile. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Shteamer, Hank (8 April 2019). "King Crimson's 50th Anniversary Press Day: 15 Things We Learned". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Fripp, Robert (4 May 2019). "Robert Fripp's Diary: Bredonborough". Discipline Global Mobile. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ Levin, Tony (9 June 2019). "Tony Levin's Road Diary: Leipzig Warmup".

- ^ "Bill Rieflin, Drummer for King Crimson, R.E.M., Ministry, Dead at 59". Rolling Stone. March 24, 2020. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- ^ a b "Have King Crimson suddenly ended – or are they on the cusp of a new cycle?". Guitar.com | All Things Guitar. 2021-12-13. Retrieved 2022-05-08.

- ^ Kielty, Martin (29 April 2022). "Gavin Harrison Says He's Unsure if King Crimson Is Finished". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 2022-05-08.

- ^ Kennelty, Greg (2022-07-16). "KING CRIMSON Is Likely Done Touring". Metal Injection. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- ^ Smith 2019, p. 84

- ^ a b "King Crimson, Greens Playhouse, 1972". DGM Live. 2018-11-27. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- ^ Live, D. G. M. (2017-04-28). "King Crimson, Heroes, 2017". DGM Live. Retrieved 2022-06-01.

- ^ "King Crimson – Formentera Lady (Instrumental Edit)". YouTube. 2 November 2020.

Although his work on the album is uncredited, Wilf [...] was the leader for the small string orchestra that appeared on Prelude Of The Gulls.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 46>

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 112–116>

- ^ "Steve Vai and Tool's Danny Carey Unite with King Crimson Musicians for 'BEAT' Tour". Rolling Stone. April 2024.

Works Cited

[edit]- Smith, Sid (2002). In The Court of King Crimson. Helter Skelter Publishing.

- Smith, Sid (2019). In The Court of King Crimson: An Observation over Fifty Years. Panegyric Publishing.