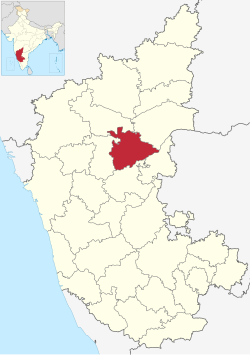

Koppal district

Koppala District | |

|---|---|

From top-left: Stone Ratha at Vittala Temple in Hampi, view of Hampi from Anjeyanadri Hill, Mahadeva Temple at Itagi, Koppal Fort, Navalinga Temple at Kuknur | |

Location in Karnataka | |

| Coordinates: 15°34′31″N 76°0′48″E / 15.57528°N 76.01333°E | |

| Country | |

| State | Karnataka |

| Division | Kalaburagi |

| Established | 24 August 1997 |

| Headquarters | Koppal |

| Taluk | Koppala, Gangavathi, Yelburga, Kushtagi, Kanakagiri, Kukanur, Karatagi |

| Government | |

| • Deputy Commissioner | Nalini Atul (IAS) |

| Area | |

• Total | 45.2 km2 (17.5 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

• Total | 1,389,920 |

| • Density | 31,000/km2 (80,000/sq mi) |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Kannada |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| PIN | 5832 |

| Telephone code | 08539 |

| ISO 3166 code | IN-KA |

| Vehicle registration |

|

| Website | koppal |

Koppala district, officially known as Koppala district is an administrative district in the state of Karnataka in India. In the past Koppal was referred to as 'Kopana Nagara'. Hampi, a World heritage center, covers some areas of Koppala District. It is situated approximately 38 km away. Anegundi, is also a famous travel destination.

History

[edit]Koppal, now a district headquarters, is ancient Kopana, a major Jain holy site. Palkigundu is described as the famous Indrakila parvata of mythology. There is an ancient Shiva temple called the Male Malleshwara. There are two Ashoka inscriptions at Palkigundu and Gavimatha. Koppal was the capital of a branch of Shilaharas under the Chalukyas of Kalyani. In Shivaji's times it was one of the eight prants or revenue divisions of Southern Maratha Country.[2] During India's First War of Independence, Mundargi Bheema Rao and Hammige Kenchanagouda died fighting the British here in June 1858. Kinhal 13 km away from Koppal is famous for its traditional colourful lacquerware.

Towns in Koppala District

[edit]- Gangavathi

- Kanakagiri

- Karatagi

- Koppala

- Kuknoor

- Kushtagi

- Munirabad

- Yalaburga

- Bhagyanagar

- Tavaragera

- Kinnal

- Shivapur

Geography

[edit]The district occupies an area of 7,190 km2 and has a population of 1,196,089, of which 16.58% was urban as of 2001.[3]

Koppal district was carved out of Raichur district in 1997.

Taluks

[edit]Koppal district has the following seven talukas: Koppal, Gangavathi, Yelburga, Kushtagi, Kanakagiri, Kuknoor and Karatagi.

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 284,184 | — |

| 1911 | 305,145 | +0.71% |

| 1921 | 290,083 | −0.50% |

| 1931 | 317,262 | +0.90% |

| 1941 | 355,851 | +1.15% |

| 1951 | 421,043 | +1.70% |

| 1961 | 465,545 | +1.01% |

| 1971 | 611,928 | +2.77% |

| 1981 | 748,222 | +2.03% |

| 1991 | 958,078 | +2.50% |

| 2001 | 1,196,089 | +2.24% |

| 2011 | 1,389,920 | +1.51% |

| source:[4] | ||

According to the 2011 census Koppal district has a population of 1,389,920,[1] roughly equal to the nation of Eswatini[6] or the US state of Hawaii.[7] This gives it a ranking of 350th in India (out of a total of 640).[1] The district has a population density of 250 inhabitants per square kilometre (650/sq mi).[1] Its population growth rate over the decade 2001-2011 was 16.32%.[1] Koppal has a sex ratio of 983 females for every 1000 males,[1] and a literacy rate of 67.28%. 16.81% of the population lives in urban areas. Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes make up 18.61% and 11.82% of the population respectively.[1]

At the time of the 2011 census, 84.09% of the population spoke Kannada, 7.34% Urdu, 4.17% Telugu, 1.64% Lambadi and 1.44% Hindi as their first language.[8]

Tourist attractions

[edit]

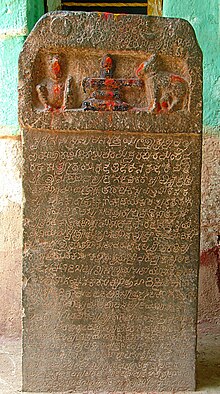

Most notable of the many buildings dating from this period[9] is the Mahadeva Temple at Itagi in the Yelabarga taluk.

The Mahadeva Temple

[edit]

The Mahadeva temple at Itagi dedicated to Shiva is among the larger temples built by the Western Chalukyas and perhaps the most famous. Inscriptions hail it as the 'Emperor among temples'.[10] Here, the main temple, the sanctum of which has a linga, is surrounded by thirteen minor shrines, each with its own linga. The temple has two other shrines, dedicated to Murthinarayana and Chandraleshwari, parents of Mahadeva, the Chalukya commander who consecrated the temple in 1112 CE.[11] Soapstone is found in abundance in the regions of Haveri, Savanur, Byadgi, Motebennur and Hangal. The great archaic sandstone building blocks used by the Badami Chalukyas were superseded with smaller blocks of soapstone and with smaller masonry.[12] The first temple to be built from this material was the Amrtesvara Temple in Annigeri in the Dharwad district in 1050 CE. This building was to be the prototype for later, more articulated structures such as the Mahadeva Temple at Itagi.[13] The 11th-century temple-building boom continued in the 12th century with the addition of new features. The Mahadeva Temple at Itagi and the Siddhesvara Temple in Haveri are standard constructions incorporating these developments. Based on the general plan of the Amrtesvara Temple at Annigeri, the Mahadeva Temple was built in 1112 CE and has the same architectural components as its predecessor. There are however differences in their articulation; the sala roof (roof under the finial of the superstructure) and the miniature towers on pilasters are chiseled instead of moulded.[14]

The difference between the two temples, built fifty years apart, is the more rigid modelling and decoration found in many components of the Mahadeva Temple. The voluptuous carvings of the 11th century were replaced with a more severe chiselling.[15]

In Karnataka their most famous temples are the Kashivishvanatha[16] temple and the Jain Narayana temple at Pattadakal, both of which are UNESCO World Heritage sites.[17] Other well known temples are the Parameshwara temple at Konnur, Brahmadeva temple at Savadi, the Settavva, Kontigudi II, Jadaragudi and Ambigeragudi temples at Aihole, Mallikarjuna temple at Ron, Andhakeshwara temple at Huli, Someshwara temple at Sogal, Jain temples at Lokapura, Navalinga Temple at Kuknur, Kumaraswamy temple at Sandur, at Shirival in Gulbarga and the Trikunteshwara temple at Gadag which was later expanded by Kalyani Chalukyas. Archeological study of these temples show some have the stellar (multigonal) plan later to be used profusely by the Hoysalas of Belur and Halebidu.[18] One of the richest traditions in Indian architecture took shape in the Deccan during this time and one writer calls it Karnata dravida style as opposed to traditional Dravida style.[19]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g "District Census Handbook: Koppal" (PDF). censusindia.gov.in. Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. 2011.

- ^ Chitnis, Krishnaji Nageshrao (1994). Glimpses of Maratha socio-economic history. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. p. 155. ISBN 81-7156-347-3. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ^ "Census GIS India". Archived from the original on 3 July 2007. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- ^ Decadal Variation In Population Since 1901

- ^ "Table C-01 Population by Religion: Karnataka". censusindia.gov.in. Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. 2011.

- ^ US Directorate of Intelligence. "Country Comparison:Population". Archived from the original on 13 June 2007. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

Swaziland 1,370,424

- ^ "2010 Resident Population Data". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

Hawaii 1,360,301

- ^ a b "Table C-16 Population by Mother Tongue: Karnataka". Census of India. Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India.

- ^ Western Chalukya architecture

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp 117–118

- ^ Rao, Kishan (10 June 2002). "Emperor of Temples' crying for attention". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 28 November 2007. Retrieved 9 November 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Cousens (1926), p 18

- ^ Foekema (2003), p 49

- ^ Foekema (2003), p 57

- ^ Foekema (2003), p 56

- ^ Rashtrakutas

- ^ Vijapur, Raju S. "Reclaiming past glory". Deccan Herald. Spectrum. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- ^ Sundara and Rajashekar, Arthikaje, Mangalore. "Society, Religion and Economic condition in the period of Rashtrakutas". 1998–2000 OurKarnataka.Com, Inc. Archived from the original on 4 November 2006. Retrieved 20 December 2006.

- ^ Sinha, Ajay J. (1999). "Reviewed work: Indian Temple Architecture: Form and Transformation, the Karṇāṭa Drāviḍa Tradition, 7th to 13th Centuries, Adam Hardy". Artibus Asiae. 58 (3/4): 358–362. doi:10.2307/3250027. JSTOR 3250027.