Kazakhs in China

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Chinese. (January 2025) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,462,588 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Xinjiang (Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture, Aksai Kazakh Autonomous County, Barkol Kazakh Autonomous County, Mori Kazakh Autonomous County) | |

| Languages | |

| Kazakh, Mandarin | |

| Religion | |

| Majority Sunni Islam, minority Tibetan Buddhism or unaffiliated | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Uyghurs, Salar people, Kyrgyz in China, Uzbeks in China |

| Kazakhs in China | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中国哈萨克族 | ||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中國哈薩克族 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Dunganese name | |||||||

| Dungan | Җунгуй хазахзў | ||||||

| Kazakh name | |||||||

| Kazakh | جۇڭگو قازاقتارى Қытайда қазақтар Qytaida qazaqtar [qɤ̆tʰaɪtá qasaχtʰáɚ] | ||||||

| Part of a series on Islam in China |

|---|

|

|

|

Kazakhs in China form the largest community of Kazakhs outside Kazakhstan. They are one of the 56 ethnic groups officially recognized by the People's Republic of China. There is one Kazakh autonomous prefecture – Ili in Xinjiang – and three Kazakh autonomous counties – Aksay in Gansu, and Barkol and Mori in Xinjiang.

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

During the fall of the Dzungar Khanate in the mid-18th century, the Manchus of the Qing Dynasty massacred the native Dzungars of Dzungaria in the Dzungar genocide, and afterwards colonized the depopulated area with immigrants from many parts of their empire. Among the peoples that moved into the depopulated Dzungaria were the Kazakhs from the Kazakh Khanates.[1]

In the 19th century, the advance of the Russian Empire troops pushed the Kazakhs to neighboring countries. Russian settlers on traditional Kazakh land drove many over the border to China, causing their population to increase in China.[2]

During the Russian Revolution, when Muslims faced conscription, Xinjiang again became a sanctuary for Kazakhs fleeing Russia.[3] During the 1920s, hundreds of thousands of Kazakh nomads moved from Soviet Kazakhstan to Xinjiang to escape Soviet persecution, famine,[note 1] violence, and forced sedentarization.[4] Kazakhs that moved to China fought for the Soviet Communist-backed Uyghur Second East Turkestan Republic in the Ili Rebellion (1944–1949).

Toops[who?] estimated that 326,000 Kazakhs, 65,000 Kirghiz, 92,000 Hui, 187,000 Han, and 2,984,000 Uyghur (totaling 3,730,000) lived in Xinjiang in 1941. Hoppe[who?] estimated that 4,334,000 people lived in Xinjiang in 1949.[5]

In 1936, after Sheng Shicai expelled 30,000 Kazakhs from Xinjiang to Qinghai, Hui Chinese led by General Ma Bufang massacred Kazakhs, until there were only 135 of them left.[6]

Modern history

[edit]The arrival of the People's Republic of China at the end of The Civil War led to significant changes in Xinjiang. The Kazakhs and other ethnic groups in the region were granted autonomy around governance, language, and religion at first, but the end goal was for the Kazakhs to integrate into the new Chinese State.[7]

In the early stages, this meant high spending on infrastructure and education, aiming to boost agricultural output and literacy respectively.[7] The arrival of the Cultural Revolution saw the end of permissiveness and the beginning of a more hardline policy, as Kazakh party cadres were purged, Islamic practice restricted, and pastoralist herds collectivized.[7] The end of pastoralism was especially harmful, as the connection to the land and nomadic lifestyle remains an important part of the Kazakh identity.[8]

In more outward ways, Xinjiang began to change as well. The Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps began a series of projects aimed at urbanising the region.[8] This, combined with the arrival of Han settlers led to a demographic shift as Kazakh areas were no longer majority Kazakh.[7] This period also saw concerns over separatism, as worsening Sino-Soviet relations saw the USSR stirring up nationalist sentiments.[7]

The end of the Cultural Revolution and rise of Deng Xiaoping led to a loosening of restrictions. The representation of Kazakhs rebounded, especially with the return of purged political leaders and Kazakhs who fled the country.[7] The collectivisation policies were also rolled back, but ethnic tensions between Kazakh and Han persist.[9]

But, there were limitations to the loosening of restrictions. The 1990s saw a wave of popular unrest and terrorist attacks that led to the Chinese Government instituting the Strike Hard campaign aimed at suppressing separatism and restoring security.[10] This and the political climate after 9/11 led to a change in policy away from cultural assimilation to securitization, as the Chinese state increasingly cracked down on separatists and Islamist terrorists.[10]

Distribution

[edit]

By province

[edit]By county

[edit](Only includes counties or county-equivalents containing >1% of county population.)

| Сounty/City | % Kazakh | Kazakh pop | Total pop |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xinjiang Uyghur autonomous region | 6.74 | 1,245,023 | 18,459,511 |

| Aksay Kazakh autonomous county | 30.5 | 2,712 | 8,891 |

| Ürümqi city | 2.34 | 48,772 | 2,081,834 |

| Tianshan district | 1.77 | 8,354 | 471,432 |

| Saybag district | 1.27 | 6,135 | 482,235 |

| Xinshi district | 1.06 | 4,005 | 379,220 |

| Dongshan district | 1.96 | 1,979 | 100,796 |

| Ürümqi county | 8.00 | 26,278 | 328,536 |

| Karamay city | 3.67 | 9,919 | 270,232 |

| Dushanzi district | 4.24 | 2,150 | 50,732 |

| Karamay district | 3.49 | 5,079 | 145,452 |

| Baijiantan district | 3.35 | 2,151 | 64,297 |

| Urko district | 5.53 | 539 | 9,751 |

| Hami city | 8.76 | 43,104 | 492,096 |

| Yizhou district | 2.71 | 10,546 | 388,714 |

| Barkol Kazakh autonomous county | 34.01 | 29,236 | 85,964 |

| Yiwu county | 19.07 | 3,322 | 17,418 |

| Changji Hui autonomous prefecture | 7.98 | 119,942 | 1,503,097 |

| Changji city | 4.37 | 16,919 | 387,169 |

| Fukang city | 7.83 | 11,984 | 152,965 |

| Midong district | 1.94 | 3,515 | 180,952 |

| Hutubi county | 10.03 | 21,118 | 210,643 |

| Manas county | 9.62 | 16,410 | 170,533 |

| Qitai county | 10.07 | 20,629 | 204,796 |

| Jimsar county | 8.06 | 9,501 | 117,867 |

| Mori Kazakh autonomous county | 25.41 | 19,866 | 78,172 |

| Bortala Mongol autonomous prefecture | 9.14 | 38,744 | 424,040 |

| Bole city | 7.10 | 15,955 | 224,869 |

| Jinghe county | 8.27 | 11,048 | 133,530 |

| Wenquan county | 17.89 | 11,741 | 65,641 |

| Ili Kazakh autonomous prefecture | 1.78 | 5,077 | 285,299 |

| Kuytun city | 1.78 | 5,077 | 285,299 |

| Ili prefecture direct-controlled territories | 22.55 | 469,634 | 2,082,577 |

| Ghulja city | 4.81 | 17,205 | 357,519 |

| Ghulja county | 10.30 | 39,745 | 385,829 |

| Qapqal Xibe autonomous county | 20.00 | 32,363 | 161,834 |

| Huocheng county | 7.96 | 26,519 | 333,013 |

| Gongliu county | 29.69 | 45,450 | 153,100 |

| Xinyuan county | 43.43 | 117,195 | 269,842 |

| Zhaosu county | 48.43 | 70,242 | 145,027 |

| Tekes county | 42.25 | 56,571 | 133,900 |

| Nilka county | 45.15 | 64,344 | 142,513 |

| Tacheng prefecture | 24.21 | 216,020 | 892,397 |

| Tacheng city | 15.51 | 23,144 | 149,210 |

| Usu city | 9.93 | 18,907 | 190,359 |

| Emin county | 33.42 | 59,586 | 178,309 |

| Shawan county | 16.23 | 30,621 | 188,715 |

| Toli county | 68.98 | 55,102 | 79,882 |

| Yumin county | 32.42 | 15,609 | 48,147 |

| Hoboksar Mongol autonomous county | 22.59 | 13,051 | 57,775 |

| Altay prefecture | 51.38 | 288,612 | 561,667 |

| Altay city | 36.80 | 65,693 | 178,510 |

| Burqin county | 57.31 | 35,324 | 61,633 |

| Koktokay county | 69.68 | 56,433 | 80,986 |

| Burultokay county | 31.86 | 24,793 | 77,830 |

| Kaba county | 59.79 | 43,889 | 73,403 |

| Qinggil county | 75.61 | 40,709 | 53,843 |

| Jiminay county | 61.39 | 21,771 | 35,462 |

Language and culture

[edit]

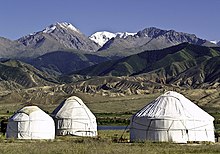

The Kazakh population in China has a distinct culture, mostly based on a series of genealogical records that in addition to stipulating lineage, keep the traditional ways of life alive.[11] Some Kazakhs are nomadic herders and raise sheep, goats, cattle, and horses. These nomadic Kazakhs migrate seasonally in search of pasture for their animals. During the summer the Kazakhs live in yurts, while in winter they settle and live in modest houses made of adobe or cement blocks. Others live in urban areas and tend to be highly educated and hold much influence in integrated communities. The Islam practiced by the Kazakhs in China contains many elements of shamanism, ancestor worship, and other traditional beliefs and practices.[12]

Kazakh is still spoken in the community, although unlike Kazakh varieties in Kazakhstan, it takes influences from Mandarin and is written in the Arabic script. Chinese Kazakhs almost always speak Uyghur or Mandarin in addition, both of which are used for interethnic communication.[13] Thus, Kazakh remains important but is seldom spoken outside the home, with the exception of Kazakh-majority areas.[13] Many Kazakhs feel ethnically distinct from other groups in Xinjiang and connected to Kazakhs across the border in Kazakhstan.[14] However, the rollback of Kazakh-medium education and the Russification of post-Soviet Kazakhs across the border means this feeling is not quite universal.[14]

Surveillance in Xinjiang

[edit]Types of surveillance

[edit]The Chinese surveillance apparatus employs extensive data collection and advanced artificial intelligence to create a more agile version of authoritarian governance, enabling it to exert unparalleled social control.[15] Chinese leaders are confident that by collecting large amounts of data, they can foresee potential threats and issues before they manifest.[16] The Chinese Communist Party has been integrating traditional surveillance techniques with cutting-edge technological innovations and biometric information to create a substantial surveillance system in Xinjiang.[17] This surveillance system includes measures such as biometric data collection (facial and iris recognition), vehicle and drone surveillance, and smartphone applications.[18] These surveillance measures extend to all aspects of life in Xinjiang, pressuring ethnic minorities to conform to government standards.[18]

Impact of surveillance

[edit]Social and cultural impact on Kazakhs

[edit]Historically, the cultural landscape allowed traditional Kazakh shrines, festivals, and religious observances, such as the annual pilgrimage to the Imam Asim shrine.[19] However, anti-terrorism and social stability policies have limited Kazakhs' freedom to express religious beliefs and participate in cultural practices.[20] This surveillance infrastructure also monitors community gatherings and religious practices, impacting the ability to openly practise Islam.[18] Since 2017, the CCP adopted a preventative approach, allegedly detaining over one million people in re-education facilities.[18] Testimonies from minority Kazakhs describe the experiences of detention, detailing physical and emotional abuses.[21] Gulbahar Haitiwaji, a detainee, recounted military-style exercises and enforced silence in the camps.[22]

Psychological and behavioural Impacts

[edit]With no strict guidelines for assessing 'transgressions,' local authorities are given discretion in interpreting and enforcing rules, solidifying Beijing's 'preventative approach' towards separatist activism.[23] The 'Grid Management System' divides communities into administrative zones with party members tasked with surveillance to maintain 'social stability.'[24] This has led to mistrust within the Kazakh community as residents are encouraged to report 'suspicious' activity among neighbours, weakening communal bonds.[24]

Surveillance and re-education camps

[edit]Impact of re-education camps

[edit]In 2017, a new policy targeted 'three threats'—terrorism, separatism, and religious radicalism.[25] Kazakhs were sent to re-education centres, temporarily removing them from the workforce.[26] This strategy enforced ideological 'development' within the centres, limiting individual liberties and reinforcing self-censorship.[26] Families faced financial strain as primary earners were detained.[26]

Financial and labour market surveillance

[edit]Surveillance heavily impacts Kazakhs, especially those involved in cross-border commerce or the local labour market. Being flagged by the state increases unemployment risk.[27] Business transactions are closely monitored, limiting economic opportunities.[28]

Mobility surveillance

[edit]Increased monitoring since 2016 has restricted ethnic Kazakhs' travel, particularly for passport acquisition, hindering their ability to leave China.[26] Surveillance checkpoints requiring ID and biometric scans further limit freedom of movement, affecting access to work, education, and family connections.[26]

Grassroots movements in Kazakhstan

[edit]Grassroots movements advocating anti-Chinese sentiment are not an unfamiliar phenomenon in Kazakhstan [29] Despite heavy Chinese investment into the relationship between Kazakhstan and China through the establishment of several Confucius institutes - non-profit organisations promoting Chinese language and culture - and a range of student exchange programs, the catalogue of anti-Chinese grievances appears to have expanded significantly since the 1990s [29] These grievances have only expanded further following the detention of ethnic Kazakhs in Xinjiang.[29]

These grassroots movements resulted in the formation of Atajurt in 2006, founded by Kazakh activist Serikzhan Bilash, which operates primarily out of Almaty in southern Kazakhstan [29] Atajurt successfully galvanised international support through collecting testimonies from those imprisoned, translating documents, and advocating on behalf of family members of detainees [30] This support was bolstered by regular press conferences held by Atajurt [31] Although the Kazakh population detained in these ‘re-education facilities’ is significantly smaller than the Uighur population,it is estimated that in the initial stages of its activism, seventy percent of the information on the facilities and its detainees came directly from Atajurt [30]

However, attempts by Atajurt to be officially recognised by Kazakh authorities were continually denied, and Serikzhan Bilash was detained in Kazakhstan in March 2019 and charged with ‘inciting ethnic hatred,’ a common means by which critics of the Kazakh government are censored.[31] Therefore, the extent to which these grassroots movements have effected change in the region is questionable.

Implications of surveillance on China's relationship with Kazakhstan and Central Asia

[edit]Xinjiang is in many respects the “main arena of the Sino-Central Asian relationship”.[29] Kazakhstan, the initial stage of China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), has cemented its relations with China over the past decade through various energy and infrastructure projects, enlarging its Gross Domestic Product by 6.5 percent [32] The reduction of trade tariffs along BRI corridors is projected to add another fifteen percent to this figure.[32]

However, these congenial relations, built on ideas of political non-interference and China's support of the Kazakh economy seems to be under increasing threat.[33] Investment into the nation has halved to $4 billion USD from the figure in 2011-2014, which was estimated at $8.1 billion USD.[34] Furthermore, China's deflating economy, paired with its ageing population, stagnating real estate market, and weakened relations with both Europe and the United States could present a challenge to relations with Central Asia, further bolstering grassroots anti-China movements within Kazakhstan.[33] Despite this, the Kazakh government has not publicly condemned nor acted against Beijing's policy in Xinjiang, and sixty-nine of China's political and economic partners have co-sponsored a statement urging for the United Nations Human Rights Commissioner to consider events in Xinjiang “China's internal affairs,” and further “opposing the politicization of human rights” [35]

Broader international impact of the surveillance of Kazakhs in Xinjiang

[edit]However, the wider global response has been remarkably different.[35] Several nations including the United States, United Kingdom and Canada have publicly asserted that Beijing's policy in Xinjiang constitutes a ‘genocide,’ and most recently, the United States has sanctioned five Chinese companies, four of which are affiliated with the surveillance device manufacturer Hikvision.[36] However, in a recent victory for China, the United Nations Human Rights Council has voted down a motion to debate and investigate Beijing's actions in Xinjiang.[37] Thus, the record is highly mixed on how China's policy in Xinjiang has impacted its relationship with Kazakhstan, Central Asia and its position on the global stage more broadly.

Notable people

[edit]- Osman Batur (1899–1951) – Kazakh chieftain who fought both for and against the Nationalist Chinese government in the 1940s and early 1950s

- Dalelkhan Sugirbayev (1906–1949) – Kazakh chieftain who fought against the Nationalist Chinese government and sought to join the Chinese Communists in 1949

- Qazhyghumar Shabdanuly (Kazakh: Қажығұмар Шабданұлы; 1925–2011) – Kazakh Chinese political activist and author writing in Kazakh language. For more than forty years, Shabdanuly was imprisoned by the People's Republic of China for his political views.

- Ashat Kerimbay (Асхат Керімбай) – Chinese politician

- Mukhtar Kul-Mukhammed (Мұхтар Абрарұлы Құл-Мұхаммед) – politician and public figure of Kazakhstan; First Deputy Chairman of "Nur Otan" party

- Janabil Jänäbil Smağululı (Жәнәбіл Смағұлұлы) – Chinese politician

- Mayra Muhammad-kyzy (Kazakh: Maıra Muhamedqyzy; Maira Kerey) – opera singer. She was the first Kazakh at the Parisian Grand Opera, and is an Honored Artist of the Republic.

- Mamer – folk singer

- Rayzha Alimjan (Риза Әлімжан; رايزا ٴالىمجان) – Kazakh Chinese actress and model

- Xiakaini Aerchenghazi (Шакен Аршынғазы) – speed skater who competed in the 2018 Winter Olympics

- Rehanbai Talabuhan – speed skater who competed in the 2018 Winter Olympics

- Adake Ahenaer (Ақнар Адаққызы) – speed skater

- Yeljan Shinar (Елжан Шынар) – footballer currently playing as a defender for Shenzhen

- Yerjet Yerzat – Chinese footballer for Chongqing Dangdai Lifan FC

- Yeerlanbieke Katai (Ерланбек Кәтейұлы) – freestyle wrestler; bronze medals winner at the 2014 Asian Games, and competed in the 2016 Summer Olympics

- Jumabieke Tuerxun – mixed martial arts fighter; he previously fought as a Bantamweight in the Ultimate Fighting Championship[38]

- Kanat Islam – boxer who won bronze medals at the 2008 Summer Olympics, 2007 World Championships, and the 2006 Asian Games

- Yushan Nijiati – amateur boxer; bronze medal winner at the 2007 World Amateur Boxing Championships in the 91 kg division

- Tuohetaerbieke Tanglatihan (Тоқтарбек Танатхан) – amateur boxer; competed in the men's middleweight event at the 2020 Summer Olympics

- Walihan Sailike (Уалихан Сайлық) – Greco-Roman wrestler; bronze medal winner in the 60 kg event at the 2018 World Wrestling Championships, and bronze medal winner in the 2020 Summer Olympics

- Ahenaer Adake (Ақнар Адақ) – speed skater; competed in the women's 1,500 meters, 3,000 meters, and team pursuit events at the 2022 Winter Olympics

- Sayragul Sauytbay (Сайрагүл Сауытбай) - doctor, headteacher, political activist & whistleblower about the Xinjiang internment camps

See also

[edit]- Kazakh exodus from Xinjiang

- Kyrgyz in China

- Dungans

- 2020 Dungan–Kazakh ethnic clashes

- Uzbeks in China

Notes

[edit]- ^ This included the Kazakh famine of 1919–1922 and Kazakh famine of 1930–1933.

References

[edit]- ^ Smagulova, Anar. "XVIII – XIX Centuries. In the Manuscripts of the Kazakhs of China". academia.edu. East Kazakhstan State University.

- ^ Alexander Douglas Mitchell Carruthers; Jack Humphrey Miller (1914). Unknown Mongolia: A Record of Travel and Exploration in North-west Mongolia and Dzungaria. Hutchinson & Company. p. 345.

- ^ Andrew D. W. Forbes (9 October 1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949. CUP Archive. pp. 17–. ISBN 978-0-521-25514-1.

- ^ Genina, Anna (2015). Claiming Ancestral Homelandsː Mongolian Kazakh migration in Inner Asia (PDF) (A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in The University of Michigan). p. 113.

- ^ Bellér-Hann, Ildikó (2008). Community Matters in Xinjiang, 1880–1949: Towards a Historical Anthropology of the Uyghur. BRILL. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-90-04-16675-2.

- ^ "Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science". American Academy of Political and Social Science. 277. A.L. Hummel: 152. 1951. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

A group of Kazakhs, originally numbering over 20000 people when expelled from Sinkiang by Sheng Shih-ts'ai in 1936, was reduced, after repeated massacres by their Chinese coreligionists under Ma Pu-fang, to a scattered 135 people.

- ^ a b c d e f Benson, L; Svanberg, I. (1988) 'The Kazakhs in Xinjiang', in L. Benson; I. Svanberg (eds.) The Kazakhs of China: Essays on an Ethnic Minority. Uppsala: Uppsala Universitet, pp. 1-107.

- ^ a b Tazhibayeva, S.Zh; Nevskaya, I.A; Mutali, A.K; Kadyskyzy, A; Absady, A.A; (2023) 'Lexical Peculiarities of Kazakh Spoken in China', Turkic Studies Journal, 5(4), pp. 130-145.

- ^ Zhang, Z; Tsakhirmaa, S, (2022) 'Ethnonationalism and the Changing Pattern of Ethnic Kazakhs’ Emigration from China to Kazakhstan', China Information, 36(3), pp. 318-343. doi:10.1177/0920203X221092686

- ^ a b Lee, M., & Yazici, E. (2023) China's Surveillance and Repression in Xinjiang. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Myunghee-no Lee-4/publication/368724121_China's_Surveillance_and_Repression_in_Xinjiang/links/64ea09400453074fbdb448cc/Chinas-Surveillance-and-Repression-in-Xinjiang.pdf -

- ^ Salimjan, Guldana (15 November 2020). "Mapping loss, remembering ancestors: genealogical narratives of Kazakhs in China". Asian Ethnicity. 22 (1): 105–120. doi:10.1080/14631369.2020.1819772. ISSN 1463-1369.

- ^ Elliot, Sheila Hollihan (2006). Muslims in China. Philadelphia: Mason Crest Publishers. pp. 62–63. ISBN 1-59084-880-2.

- ^ a b S.Zh. Tazhibayeva, S.Zh. Tazhibayeva; I.A. Nevskaya, I.A. Nevskaya; A.K. Mutali, A.K. Mutali; A. Kadyskyzy, A. Kadyskyzy; A.A. Absady, A.A. Absady (2023). "Lexical Peculiarities of Kazakh Spoken in China". Turkic Studies Journal. 5 (4): 130–145. doi:10.32523/2664-5157-2023-4-130-145. ISSN 2664-5157.

- ^ a b Zhang, Zhe; Tsakhirmaa, Sansar (11 May 2022). "Ethnonationalism and the changing pattern of ethnic Kazakhs' emigration from China to Kazakhstan". China Information. 36 (3): 318–343. doi:10.1177/0920203x221092686. ISSN 0920-203X.

- ^ Kuo, M.A. (2022) "Surveillance State: Social control in China," The Diplomat, 3 October. Available at: https://thediplomat.com/2022/10/surveillance-state-social-control-in-china/

- ^ Kuo, 2022

- ^ Lee, M., & Yazici, E. (2023) "China’s Surveillance and Repression in Xinjiang." Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/368724121_China's_Surveillance_and_Repression_in_Xinjiang

- ^ a b c d Lee & Yazici, 2023

- ^ Dillon, M. (2018) Xinjiang in the Twenty-First Century: Islam, Ethnicity and Resistance. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315749341

- ^ Dillon, 2018

- ^ Kaşikçi, 2020

- ^ Haitiwaji, G., & Morgat, M. (2021) Gulbahar Haitiwaji's account

- ^ Hasmath, R. (2022) "Future Responses to Managing Muslim Ethnic Minorities in China," International Journal, 77(1), pp. 51-67. doi:10.1177/00207020221097991

- ^ a b Hasmath, 2022

- ^ Zhang, Z., & Tsakhirmaa, S. (2022) "Ethnonationalism and the Changing Pattern of Ethnic Kazakhs’ Emigration from China," China Information, 36(3), pp. 318-343. doi:10.1177/0920203X221092686

- ^ a b c d e Zhang & Tsakhirmaa, 2022

- ^ Karimova, R., & Khajiyeva, G. (2018) "Examining ethno-political and socio-economic transformation of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region", News of the National Academy of Sciences of Kazakhstan, Series of Social and Humanities, 6(322), pp. 176–184.

- ^ Karimova & Khajiyeva, 2018

- ^ a b c d e Proń, E. & Szwajnoch, E. (2020) ‘KYRGYZ AND KAZAKH RESPONSES TO CHINA’S XINJIANG POLICY UNDER XI JINPING’, Asian Affairs, 51(4), pp. 761–778. doi:10.1080/03068374.2020.1827547.

- ^ a b Kaşıkçı, M. V. (2020), ‘Documenting the Tragedy in Xinjiang: An Insider's View of Atajurt’, The Diplomat

- ^ a b Standish, R. & Toleukhanova, A. (2021), ‘Kazakh Activism Against China's Internment Camps Is Broken, But Not Dead’, RadioFreeEurope RadioLiberty

- ^ a b World Bank. (2020), ‘South Caucasus and Central Asia: The Belt and Road Initiative -Kazakhstan Country Case Study’, pp. 1–21

- ^ a b Nelson, H. (2023) ‘The Hidden Costs of Kazakhstan's Engagement with China: A Decade of the Belt and Road’, Caspian Policy Centre

- ^ • Umarov, T. (2019) ‘What's Behind Protests Against China in Kazakhstan?’, Carnegie Endowment For International Peace

- ^ a b Maizland, L. (2022), ‘China's Repression of Uyghurs in Xinjiang’, Council on Foreign Relations

- ^ Al Jazeera. (2023), ‘US sanctions Chinese firms over alleged repression of Uighurs’

- ^ Farge, E. (2022), ‘U.N. body rejects debate on China's treatment of Uyghur Muslims in blow to West’, Reuters

- ^ "Jumabieke Tuerxun: From The Rural Edges of China to the UFC". Fightland. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- Benson, L; Svanberg, I. (1988) The Kazakhs in Xinjiang, in L. Benson; I. Svanberg (eds.) The Kazakhs of China: Essays on an Ethnic Minority. Uppsala: Uppsala Universitet, pp. 1–107.

- Tazhibayeva, S.Zh; Nevskaya, I.A; Mutali, A.K; Kadyskyzy, A; Absady, A.A; (2023) "Lexical Peculiarities of Kazakh Spoken in China", Turkic Studies Journal, 5(4), pp. 130–145. Available at:

- Salimjan, G. (2021) "Mapping Loss, Remembering Ancestors: Genealogical Narratives of Kazakhs in China," Asian Ethnicity, 22(1), pp. 105–120. doi:10.1080/14631369.2020.1819772