Kaunas pogrom

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Polish. (December 2023) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

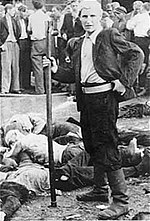

The Kaunas pogrom was a massacre of Jews living in Kaunas, Lithuania, that took place on 25–29 June 1941; the first days of Operation Barbarossa and the Nazi occupation of Lithuania. The most infamous incident occurred at the garage of NKVD Kaunas section, a nationalized garage of Lietūkis, an event known as the Lietūkis Garage Massacre.[1] There several dozen Jewish men, allegedly associates of NKVD, were publicly tortured and executed on 27 June in front of a crowd of Lithuanian men, women and children. The incident was documented by a German soldier who photographed the event as a man, nicknamed the "Death Dealer", beat each man to death with a metal bar. After June, systematic executions took place at various forts of the Kaunas Fortress, especially the Seventh and Ninth Fort.[2]

Background

[edit]

The Lithuanian Activist Front (LAF), a far-right underground organisation operating inside Soviet Lithuania, took control of the city[4] and much of the Lithuanian countryside on the evening of 23 June 1941. Nazi SS Brigadeführer Franz Walter Stahlecker arrived in Kaunas on the morning of 25 June. He visited the headquarters of the Lithuanian Security Police and delivered a long anti-Semitic speech encouraging Lithuanians to solve the "Jewish problem".[5] According to Stahlecker's report of 15 October, local Lithuanians were not enthusiastic about the pogrom and so he had to use Algirdas Klimaitis and his men.[5] Klimaitis controlled a paramilitary unit of approximately 600 men that was organized in Tilsit by SD and was not subordinated to the LAF.[5]

Massacre

[edit]

Starting on 25 June, Nazi-organized units attacked Jewish civilians in Slobodka (Vilijampolė), a Jewish suburb of Kaunas that hosted the world-famous Slabodka yeshiva. According to Rabbi Ephraim Oshry, Germans were present on the bridge to Slobodka, but it was the Lithuanian volunteers who killed the Jews. The rabbi of Slobodka, Rav Zalman Osovsky, was tied hand and foot to a chair, "then his head was laid upon an open volume of gemora (volume of the Talmud) and [they] sawed his head off", after which they murdered his wife and son. His head was placed in a window of the residence, bearing a sign: "This is what we'll do to all the Jews."[6]

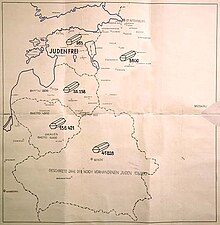

As of 28 June 1941, according to Stahlecker, 3,800 people had been killed in Kaunas and a further 1,200 in other towns in the immediate region.[4] Some believe Stahlecker exaggerated his murder tally.[7][8]

Karl Jaeger, the Nazi commander of the mobile killing squad Einsatzkommando 3, wrote on December 1, 1941, that Nazis and Lithuanian partisans killed 7,800 Jews in Kovno between June 24, 1941, and July 6, 1941.[9] Jaeger recorded 4,000 Jews in Kovno that were killed exclusively by Lithuanian partisans.[9] (See Jaeger Report).

Controversy

[edit]

The primary responsibility for initiating the massacres has been disputed, whether local Lithuanians or Nazi officials.

Memoirs of witnesses say that German Nazi soldiers in uniform participated in Lietūkis' sadistic tortures and massacres, but were also accompanied by Lithuanians recently freed from Kaunas Prison.[10]

Franz Walter Stahlecker's report of 15 October to Heinrich Himmler said that he had succeeded in covering up actions of the Vorkommando (German vanguard unit) and made it look like an initiative of the local population.[5][failed verification]

Other authors claim that massacres began even before the Germans arrived.[11] They point out that executions took place in the countryside and not just in the city of Kaunas. Photography experts have suggested that many pictures from the Kaunas pogrom might have been falsified by gluing multiple pictures into one because there are many discrepancies in the pictures (e.g., different walls, doors locations, illumination and perspectives do not match).[12] The infamous Death Dealer with blonde hair may not have been a Lithuanian. There is speculation that he was German SS officer Joachim Hamann. Hamann was commanding officer of Rollkommando Hamann, a mobile killing unit attached to Einsatzkommando 3 that was active in the territory at the time.[13] Historian Arvydas Anušauskas, an author of the film about the massacre, is sceptical about these theories, because, in addition to the photos, there are witness testimonies, as well as the testimony of the photographer, Wilhelmas Gunsilius (which his will made public 10 years after his death).[12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Dov Segal, "The Lietūkis Garage Massacre", The Jerusalem Post, August 8, 2017

- ^ Arvydas Anušauskas; et al., eds. (2005). Lietuva, 1940–1990 (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Lietuvos gyventojų genocido ir rezistencijos tyrimo centras. p. 203. ISBN 9986-757-65-7.

- ^ "The Death Dealer of Kovno - Beachcombing's Bizarre History Blog". 31 March 2011.

- ^ a b MacQueen, Michael (1998). "Nazi Policy towards the Jews in the Reichskommissariat Ostland, June–December 1941: From White Terror to Holocaust in Lithuania". In Gitelman, Zvi (ed.). Bitter Legacy: Confronting the Holocaust in the USSR. Indiana University Press. p. 97. ISBN 0-253-33359-8.

- ^ a b c d Bubnys, Arūnas (2003). "Lietuvių saugumo policija ir holokaustas (1941–1944)". Genocidas Ir Rezistencija (in Lithuanian). 13. ISSN 1392-3463. English translation of excerpts from Stahlecker's report available here: "The Einsatzgruppen: Report by Einsatzgruppe A in the Baltic Countries (October 15, 1941)". Jewish Virtual Library. American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise. Retrieved 2015-03-29.

- ^ Oshry, Ephraim (1995). Annihilation of Lithuanian Jewry. New York: Judaica Press, Inc. p. 3. ISBN 1-880582-18-X.

- ^ Budreckis, Algirdas M. (1968). The Lithuanian National Revolt of 1941. Boston: Lithuanian Encyclopedia Press. pp. 62–63. OCLC 47283.

Again for some unknown reason, Stahlecker exaggerates his statistics. The account by L. Shauss to the Soviet Extraordinary State Commission stated that in "the first pogrom on June 25–26, in the Kaunas suburb of Slobodka (Vilijampolė), 600 Jews were killed on Arbarski, Paverski, Vilyuski, Irogalski streets."

- ^ Sužiedėlis, Saulius (Winter 2001). "The Burden of 1941". Lituanus. 4 (47). ISSN 0024-5089. Archived from the original on 2012-09-15. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

On the other hand, notwithstanding a number of such incidents, the available evidence does not support the image of huge mobs of locals hunting down Jews by the thousands even before the arrival of the Germans as some have claimed.

- ^ a b Faitelson, Alex (2006). The Truth and Nothing But the Truth: Jewish Resistance in Lithuania. Gefen Books. p. 76. ISBN 965-229-364-4.

- ^ Valiušaitis, Vidmantas; Mošinskis, Algirdas (2021-06-27). ""Lietūkio" garažo žudynės – vienas kraupiausių ir mįslingiausių Lietuvos istorijos epizodų". Alkas.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ Greenbaum, Masha (1995). The Jews of Lithuania: A History of a Remarkable Community 1316–1945. Gefen Publishing House. p. 307. ISBN 9789652291325.

- ^ a b Varnauskas, Rimantas (2007-04-02). ""Lietūkio" garažas - klastočių pinklėse?". delfi.lt. Retrieved 2021-05-04.

- ^ "'Lietūkio' garažo tragedija". Lzinios.lt. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2007.