Just Like a Woman

| "Just Like a Woman" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

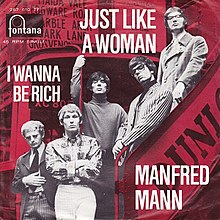

West German picture sleeve | ||||

| Single by Bob Dylan | ||||

| from the album Blonde on Blonde | ||||

| B-side | "Obviously 5 Believers" | |||

| Released | August 18, 1966 | |||

| Recorded | March 8, 1966 | |||

| Studio | Columbia, Nashville | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length |

| |||

| Label | Columbia | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Bob Dylan | |||

| Producer(s) | Bob Johnston | |||

| Bob Dylan singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Audio | ||||

| "Just Like a Woman" on YouTube | ||||

"Just Like a Woman" is a song by the American singer-songwriter Bob Dylan from his seventh studio album, Blonde on Blonde (1966). The song was written by Dylan and produced by Bob Johnston. Dylan allegedly wrote it on Thanksgiving Day in 1965, though some biographers doubt this, concluding that he most likely improvised the lyrics in the studio. Dylan recorded the song at Columbia Studio A in Nashville, Tennessee in March 1966. The song has been criticized for sexism or misogyny in its lyrics, and has received a mixed critical reaction. Some critics have suggested that the song was inspired by Edie Sedgwick, while other consider that it refers to Dylan's relationship with fellow folk singer Joan Baez. Retrospectively, the song has received renewed praise, and in 2011, Rolling Stone magazine ranked Dylan's version at number 232 in their list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time. A shorter edit was released as a single in the United States during August 1966 and peaked at number 33 on the Billboard Hot 100. The single also reached 8th place in the Australian charts, 12th place on the Belgium Ultratop Wallonia listing, 30th in the Dutch Top 40, and 38th on the RPM listing in Canada.

Though a relative success in the United States, Dylan's recording of "Just Like a Woman" was not issued as a single in the United Kingdom. However, British beat group Manfred Mann recorded a version of the song in June 1966 for their album As Is, during their first recording session together with producer Shel Talmy. In July, it became Manfred Mann's first single to be released through Fontana Records. It was a hit in several European countries, reaching number 10 in the UK Singles Chart and number 1 in Sweden. The song received positive reviews from critics, several of whom highlighted Mike d'Abo's vocal performance.

Background and recording

[edit]

Bob Dylan released his fifth studio album Bringing It All Back Home in March 1965, followed by Highway 61 Revisited in August of that year.[5] In October, he began recording sessions for this next album Blonde on Blonde.[6] After several sessions in New York,[7] the recording was relocated to Nashville following a suggestion by Dylan's producer Bob Johnston.[8] Two musicians from the New York sessions were retained; Dylan was accompanied by Al Kooper on his journey to Nashville and Robbie Robertson joined them there.[3]

The master take of "Just Like a Woman" was produced by Johnston and recorded at Columbia Studio A, Nashville, Tennessee on March 8, 1966.[9] Seven complete takes, and multiple rehearsals and partial takes were recorded. Take 18, the last of the session, was used on the album,[10] which was released on June 20, 1966.[11]

The song features a lilting melody, backed by delicately picked nylon-string guitar and piano instrumentation, resulting in what Bill Janovitz wrote was arguably the most "radio-friendly" track on the album.[12] The musicians backing Dylan on the track are Charlie McCoy, Joe South, and Wayne Moss on guitar, Henry Strzelecki on bass guitar, Hargus "Pig" Robbins on piano, Kooper on organ, and Kenneth Buttrey on drums.[12][10] Although Dylan's regular guitar sideman Robertson was present at the recording session, he did not play on the song.[12]

The album version is 4 minutes and 53 seconds long.[4][a] A single version, edited down to 2 minutes and 56 seconds, was released in the United States on August 18, 1966, and in other countries, not including the United Kingdom, in the same year.[13][14] Musicologist Larry Starr noted that Dylan employed a traditional AABA structure in the song, and that, unusually for him, the bridge literally bridges over into the next section of the song: "Ain't it clear that –[new section] I just can't fit."[15]

Composition and lyrical interpretation

[edit]In the album notes of his 1985 compilation Biograph, Dylan related that he wrote the lyrics of "Just Like a Woman" in Kansas City on Thanksgiving Day, November 25, 1965, while on tour.[16] However, after listening to the recording session tapes of Dylan at work on the song in the Nashville studio, historian Sean Wilentz has written that he improvised the lyrics in the studio by singing "disconnected lines and semi-gibberish". Dylan was initially unsure what the person described in the song does that is just like a woman, rejecting "shakes", "wakes", and "makes mistakes". The improvisational spirit extends to the band attempting, in their fourth take, a "weird, double-time version", somewhere between Jamaican ska and Bo Diddley.[17]

Clinton Heylin has analyzed successive drafts of the song from the so-called Blonde On Blonde papers, documents that Heylin believes were either left behind by Dylan or stolen from his Nashville hotel room.[18] The first draft has a complete first verse, a single couplet from the second verse, and another couplet from the third verse. There is no trace of the chorus of the song. In successive drafts, Dylan added sporadic lines to these verses, without ever writing out the chorus. This leads Heylin to speculate that Dylan was writing the words while Kooper played the tune over and over on the piano in the hotel room, and the chorus was a "last-minute formulation in the studio".[19] Kooper has explained that he would play piano for Dylan in his hotel room, to aid the song-writing process, and then would teach the tunes to the studio musicians at the recording sessions.[20]

Dylan's exploration of female wiles and feminine vulnerability was widely rumored—"not least by her acquaintances among Andy Warhol's Factory retinue"—to be about Edie Sedgwick.[21][22] The reference to Baby's penchant for "fog, amphetamine and pearls" suggests Sedgwick or someone similar, according to Heylin.[19] "Just Like a Woman" has also been rumored to have been written about Dylan's relationship with fellow folk singer Joan Baez.[12] In particular, it has been suggested that the lines "Please don't let on that you knew me when/I was hungry and it was your world" may refer to the early days of their relationship, when Baez was more famous than Dylan.[12] Ralph J. Gleason of the San Francisco Examiner considered that the song was "achingly autobiographical".[23]

The subject of the song is said by the narrator to have lost "ribbons and bows" from her hair. Timothy Hampton suggested that this references songs such as "Buttons and Bows" and "Scarlet Ribbons (For Her Hair)" that use the image as one of femininity, although "these traces of an earlier age of innocent song and wholesome girlhood are modernized when they are juxtaposed with the 'hip' images of amphetamines and 'fog'" in "Just Like a Woman".[24]

Alleged sexism

[edit]The song, like others by Dylan, has been criticized for sexism or misogyny in its lyrics.[25][26][27] Alan Rinzler, in his book Bob Dylan: The Illustrated Record, describes the song as "a devastating character assassination...the most sardonic, nastiest of all Dylan's putdowns of former lovers".[28] In 1971, Marion Meade wrote in The New York Times that "there's no more complete catalogue of sexist slurs", and went on to note that in the song Dylan "defines women's natural traits as greed, hypocrisy, whining and hysteria".[27][29] Dylan biographer Robert Shelton noted that "the title is a male platitude that justifiably angers women," although Shelton believed that "Dylan is ironically toying with that platitude".[27]

Countering allegations of misogyny, music critic Paul Williams, in his book Bob Dylan: Performing Artist, Book One 1960–1973, pointed out that Dylan sings in an affectionate tone from beginning to end.[30] He further comments on Dylan's singing by saying that "there's never a moment in the song, despite the little digs and the confessions of pain, when you can't hear the love in his voice".[31] Williams also contends that a central theme of the song is the power that the woman described in the lyrics has over Dylan, as evidenced by the line "I was hungry and it was your world".[32]

Janovitz, in his AllMusic review, noted that in the context of the song, Dylan "seems on the defensive... as if he has been accused of causing the woman's breakdown. But he takes some of the blame as well". Janovitz concluded by noting, "It is certainly not misogynist to look at a personal relationship from the point of view of one of those involved, be it man or woman. There is nothing in the text to suggest that Dylan has a disrespect for, much less an irrational hatred of, women in general."[12] Similarly, literary critic Christopher Ricks asks, "could there ever be any challenging art about men and women where the accusation just didn't arise?"[33] Moreover, Gill has argued that the key "delimitation" in the song is not between man and woman, but between woman and girl, so the issue is one "of maturity rather than gender".[21]

Critical reception

[edit]David F. Wagner, in The Post-Crescent, found "Just Like a Woman" to be a "tender, melodic ballad with punch", that he felt would be the most-covered track from the album.[34] The critic for the Runcorn Weekly News preferred Dylan's original to the cover by Manfred Mann, and wrote that "it has more meaning when Dylan sings it".[35] The Asbury Park Press columnist Don Lass described the song as "an evocative, lyrical, almost painful love song".[36] A Billboard reviewer considered Dylan in "top-form with this much recorded bluesy ballad".[37] A staff writer for Cash Box described the song as "a slow-shufflin' laconic ode which underscores just how much men need woman [sic]".[38] The staff writer for Record World believed that Dylan went after a more relaxed "musical background than usual on this ditty", calling the lyrics "perceptive".[39]

The Sun-Herald's reviewer dismissed what they referred to as the "pop songs" on Blonde on Blonde, including "Just Like a Woman": "the fancy words are inclined to hide the fact that there is nothing there at all".[40] Craig McGregor of The Sydney Morning Herald found the song "overly sentimental".[41] "The Arizona Republic reviewer Troy Irvine described the single release version as "a bright mover with good folk appeal".[42]

Retrospectively, critic Michael Gray likewise called the song "uncomfortably sentimental. The chorus is trite and coy and the verses aren't strong enough to compensate."[43] Gray highlights the lines "...she aches just like a woman/But she breaks just like a little girl", commenting that "What parades as reflective wisdom... is really maudlin platitude".[43] He did, however, praise the middle eight due to Dylan's delivery of the words.[44] In 2011, Rolling Stone magazine ranked Dylan's version of the song at number 232 in their list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.[45] In 2013, Jim Beviglia rated it as the 17th-best of Dylan's songs, and praised the instrumental performances as "just about perfect [for] a studio recording".[46]

Live versions and later releases

[edit]According to his official website, Dylan played the song live in concert 871 times from 1966 to 2010.[47] In his 1966 tour performances, Dylan chose to play the song solo rather than with the band that accompanied him on the tour.[48] Starr commented that although the original album version is "notable for its understated accompaniment to Dylan's subtle and expressive vocals", in his performance at Manchester on May 17, 1966, Dylan "seem[ed] intent, if anything, to exceed the sense of intimacy he had achieved in the studio".[49]

In addition to its appearance on Blonde on Blonde, "Just Like a Woman" also appears on several Dylan compilations, including Bob Dylan's Greatest Hits (1967), Masterpieces (1978), Biograph (1985), The Best of Bob Dylan, Vol. 1 (1997), The Essential Bob Dylan (2000), and Dylan (2007).[12] The "Just Like a Woman" recording session was released in its entirety on the 18-disc Collector's Edition of The Bootleg Series Vol. 12: The Cutting Edge 1965–1966 in 2015, with highlights from the outtakes appearing on the 6-disc and 2-disc versions of the album.[50]

Live recordings of the song have been included on Before the Flood (1974), Bob Dylan at Budokan (1979), The Bootleg Series Vol. 4: Bob Dylan Live 1966, The "Royal Albert Hall" Concert (1998), The Bootleg Series Vol. 5: Bob Dylan Live 1975, The Rolling Thunder Revue (2002).[47] In June 2019, five live performances of the song from the 1975 Rolling Thunder Revue tour were released in the box set The Rolling Thunder Revue: The 1975 Live Recordings.[47] Dylan performed the song at George Harrison and Ravi Shankar's The Concert for Bangladesh in 1971, and his performance is featured on the Concert for Bangladesh album.[51]

Credits and personnel

[edit]The details of the personnel involved in making Blonde on Blonde are subject to some uncertainty.[52] The credits below are adapted from the Bob Dylan All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Track book.[4]

Musicians

- Bob Dylan – vocals, guitar, harmonica

- Charlie McCoy – guitar

- Joe South – guitar

- Wayne Moss – guitar

- Al Kooper – organ

- Hargus "Pig" Robbins – piano

- Henry Strzelecki – bass guitar

- Kenneth Buttrey – drums

Technical

- Bob Johnston – record producer

Manfred Mann version

[edit]| "Just Like a Woman" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Dutch picture sleeve | ||||

| Single by Manfred Mann | ||||

| from the album As Is | ||||

| B-side | "I Wanna Be Rich" | |||

| Released | July 29, 1966 | |||

| Recorded | June 30, 1966 | |||

| Studio | Philips, Marble Arch, London | |||

| Length | 2:46 | |||

| Label | Fontana | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Bob Dylan | |||

| Producer(s) | Shel Talmy | |||

| Manfred Mann singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Audio | ||||

| "Just Like a Woman" on YouTube | ||||

Background and recording

[edit]

English beat group Manfred Mann formed in December 1962 (originally as the Mann-Hugg Blues Brothers), and signed to record label His Master's Voice in May 1964.[53] By mid-1966, the group had started to break up.[54] They enjoyed the success of their single "Pretty Flamingo", which had become their second song to reach number-one on the Record Retailer chart.[55] However, internally, Manfred Mann had begun splitting.[54] Vocalist Paul Jones gave the group a year's notice that he would be leaving to pursue a solo career.[56][57] After a car accident in early 1966, which left Jones unable to perform, Manfred Mann hired bassist Jack Bruce along with brass players and cut some instrumental songs.[57][58] However, during the success of "Pretty Flamingo", Jones convinced the record label about recording solo in May of that year, when the group's three-year contract expired.[57] His Master's Voice decided to sign Jones as a solo artist in June 1966, leaving the other members without a record label or contract.[58][59]

Bruce had by this point also left to form Cream with Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker, also leaving Manfred Mann without a bassist.[60] The solution came when they hired bassist Klaus Voormann, and singer Mike d'Abo after seeing him perform on the show There's a Whole Scene Going.[61][62] d'Abo, who had recently quit his band, accepted the offer to join.[57] In June 1966, the group signed a contract with Fontana Records and on June 8, recorded their first two tracks with Voormann and d'Abo, "I Wanna Be Rich" and "Let It Be Me".[57][63] This collaboration proved fruitful, with them staying on the label for the rest of their career.[57]

Producer Shel Talmy had previously helped Manfred Mann secure an audition for Decca Records in 1963, though that ultimately went nowhere.[64] Talmy, who had produced for such artists as the Kinks, the Who, and David Bowie,[65] was aware that the members were fans of Dylan's music. The group had scored a hit with another Dylan composition, "If You Gotta Go, Go Now" the previous year, and Talmy suggested that they record another Dylan song.[64] Additionally, Manfred Mann's previous manager Kenneth Pitt was Dylan's British publicist, giving them access to demos and otherwise unavailable material.[66] The song features the signature steel guitar playing by Tom McGuinness,[67] though notably lacks any significant keyboard parts unlike much of their earlier material.[54] The group recorded it on June 30, 1966, at Phillips Studio in Marble Arch with Talmy producing.[64][63]

Release and reception

[edit]Fontana Records released "Just Like A Woman" as Manfred Mann's debut single on their label on July 29, 1966.[64][68] Coincidentally, a version by Jonathan King was released on the same day by Decca Records,[69] which led to a feud in the charts over whose version would be more successful.[70] Another coincidence is the fact that both these versions were released on the same day Dylan crashed his motorcycle, effectively putting him out of the spotlight for well over a year.[71] Manfred Mann's version was backed by "I Wanna Be Rich", which was written by the group's drummer Mike Hugg.[67][72] Though Hugg thought that it was most likely a safe choice for their debut single with d'Abo, the band's eponym and keyboard player Manfred Mann disagreed, stating that the release of the single was "the most stressful moment in my whole musical career", and recounted that he was depressed when it initially did not receive any radio play.[67] The song was included on the band's album As Is, released in October 1966.[57]

The song entered the Record Retailer chart on August 10, at a position of 37.[55] It peaked at number 10 for the week of September 21, before exiting the chart on October 12, at a position of 38.[55] The song spent 10 weeks on the Record Retailer chart.[55] King's version however, only reached number 56,[55] which, according to Bruce Eder of AllMusic, meant that Manfreds chart success "establish[ed] the new lineup's commercial credibility".[57] It reached number nine in Disc and Music Echo,[73] number 12 in Melody Maker and eight in the New Musical Express chart.[74][75] It was also a number one in Sweden[76][77] and a top ten hit in both Denmark and Finland.[78][79] In the US however, it barely dented the charts, only reaching number 101 on the Billboard Bubbling Under Hot 100 chart.[80]

The track was well received by critics upon release. In Disc and Music Echo, Penny Valentine reviewed both Manfred Mann's and King's versions, but preferred the former, calling it more "subtle" and "far more pretty".[81] She attributed this to d'Abo's "breathing away sexily", though she believed the song would do better in the charts if Jones had been the lead vocalist.[81] Norman Jopling and Peter Jones of Record Mirror felt that the song would be a big hit, stating that d'Abo's vocals "work perfectly" within the frame of the song, while comparing the group backing to Dylan's work.[82] They concluded by stating that it was a "fine-tempoed arrangement".[82] In Billboard magazine, the reviewer called the track a "strong debut" and predicted to reach the Billboard Hot 100.[83] A Cash Box staff writer described it as a "harsh, funk-filled reading", which the reviewer thought would generate sales for the single.[84]

Charts

[edit]

|

|

Notes

[edit]- ^ Some sources vary slightly on the timing, e.g. the Searching for a Gem site gives 4:54

References

[edit]Books

- Beviglia, Jim (2013). Counting Down Bob Dylan: His 100 Finest Songs. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-8824-1.

- Clapton, Eric (2007). Clapton: The Autobiography. New York City: Broadway Books. pp. 74, 77. ISBN 978-0-385-51851-2.

- Brown, Tony (2000). The Complete Book of the British Charts. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-7670-2.

- Gill, Andy (1998). Classic Bob Dylan: My Back Pages. Carlton. ISBN 978-1-85868-599-1.

- Gray, Michael (2004). Song and Dance Man III: The Art of Bob Dylan. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-6382-1.

- Hampton, Timothy (2020). Bob Dylan: How the Songs Work (Kindle ed.). Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-942130-36-9.

- Heylin, Clinton (1995). Dylan: Behind Closed Doors – the Recording Sessions (1960–1994). Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-025749-6.

- Heylin, Clinton (2009). Revolution in the Air: The Songs of Bob Dylan, Volume One: 1957–73. Constable & Robinson. ISBN 978-1-84901-051-1.

- Heylin, Clinton (2016). Judas!: From Forest Hills to the Free Trade Hall: A Historical View of Dylan's Big Boo (Kindle ed.). Route Publishing. ISBN 978-1-901927-68-9.

- Heylin, Clinton (2021). The Double Life of Bob Dylan. Vol. 1 1941-1966, A Restless, Hungry Feeling. London: The Bodley Head. ISBN 978-1-84792-588-6.

- McGuinness, Tom (1997). Manfred Mann - The Fontana Years (CD). Spectrum Music. 552 375-2.

- Larkin, Colin (2006). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music: Grenfell, Joyce – Koller, Hans. MUZE. ISBN 978-0-19-531373-4.

- Margotin, Philippe; Guesdon, Jean-Michel (2022). Bob Dylan All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Track (Expanded ed.). New York: Black Dog & Leventhal. ISBN 978-0-7624-7573-5.

- Miles, Barry (2009). The British Invasion. Sterling Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4027-6976-4.

- Rees, Dafydd; Crampton, Luke, eds. (1991). Book of Rock Stars (2nd ed.). Enfield: Guinness. ISBN 978-0-85112-971-6.

- Russo, Greg (2011). Mannerisms: The Five Phases of Manfred Mann. Crossfire Publications. ISBN 978-0-9791845-2-9.

- Sanders, Daryl (2020). That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound: Dylan, Nashville, and the Making of Blonde on Blonde (epub ed.). Chicago: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-61373-550-3.

- Savage, Jon (2015). 1966: The Year the Decade Exploded. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-27764-3.

- Shelton, Robert (1997) [1986]. No Direction Home. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80782-4.

- Sounes, Howard (2001). Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-1686-4.

- Starr, Larry (2021). Listening to Bob Dylan. Music in American Life (Kindle ed.). Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-05288-0.

- Tobler, John (1992). NME Rock 'N' Roll Years (first ed.). London: Reed International Books. CN 5585.

- Trager, Oliver (2004). Keys to the Rain: The Definitive Bob Dylan Encyclopedia. Billboard Books. ISBN 978-0-8230-7974-2.

- Wilentz, Sean (2009). Bob Dylan in America. The Bodley Head. ISBN 978-1-84792-150-5.

- Wilentz, Sean (2010). "4: The Sound of 3:00 am: The Making of Blonde on Blonde, New York City and Nashville, October 5, 1965 – March 10 (?), 1966". Bob Dylan in America. London: Vintage Digital. ISBN 978-1-4070-7411-5. Retrieved August 21, 2022 – via PopMatters.

- Williams, Paul (2004) [1990]. Bob Dylan, Performing Artist: The Early Years, 1960–1973. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84449-095-0.

- Yaffe, David (2011). Like a Complete Unknown. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12457-6.

Citations

- ^ "10 Greatest Bob Dylan Songs". Rolling Stone. August 29, 2019.

- ^ "Bob Dylan - Blonde on Blonde :: Le Pietre Miliari di OndaRock".

- ^ a b Heylin 2021, pp. 388–392.

- ^ a b c Margotin & Guesdon 2022, p. 232.

- ^ Williams 2004, p. 284.

- ^ Heylin 1995, p. 46.

- ^ Heylin 1995, p. 45-46.

- ^ Heylin 2021, pp. 388–389.

- ^ Sanders 2020, p. 99.

- ^ a b Björner, Olof (June 3, 2011). "1966 Blonde on Blonde sessions and world tour". Still on the Road. Archived from the original on October 26, 2019. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ^ Heylin 2016, 7290: a Sony database of album release dates ... confirms once and for all that it came out on June 20, 1966"..

- ^ a b c d e f g Janovitz, Bill. "Just Like a Woman". AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 15, 2017. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ^ Fraser, Alan. "Rarities Alphabetical Listing by Song Title: F-J". Searching for a Gem. Archived from the original on February 14, 2022. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ Fraser, Alan. "Audio: 1966 – Just Like A Woman". Searching for a Gem. Archived from the original on March 24, 2022. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ Starr 2021, 1443.

- ^ Biograph, Bob Dylan, 1985, Liner notes & text by Cameron Crowe.

- ^ Wilentz 2009, p. 122

- ^ Heylin 2009, p. 299

- ^ a b Heylin 2009, pp. 303–304

- ^ Gill 1998, p. 94.

- ^ a b Gill 1998, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Yaffe 2011, p. 9.

- ^ "Dylan's 'Blonde' broke all the rules". San Francisco Examiner. July 31, 1966. p. TW.31.

- ^ Hampton 2020, p. 103.

- ^ "Was Bob Dylan's 'Just Like A Woman' misogynistic?". faroutmagazine.co.uk. March 23, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ March, Anna (May 17, 2016). "Just like a woman: I'm a feminist and I love Bob Dylan—even though I know I shouldn't". Salon. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ a b c Shelton 1997, p. 323.

- ^ Williams 2004, p. 190.

- ^ Trager 2004, pp. 347–348.

- ^ Williams 2004, pp. 190–192.

- ^ Williams 2004, pp. 191.

- ^ Williams 2004, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Ricks, Christopher (January 30, 2009). "Just Like a Man? John Donne, T.S. Eliot, Bob Dylan, and the Accusation of Misogyny". MBL. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ^ Wagner, David F. (July 31, 1966). "Bob Dylan is 20th century romantic". The Post-Crescent. p. S10.

- ^ C. H. (August 18, 1966). "Your LP corner". Runcorn Weekly News. p. 5.

- ^ Lass, Don (December 24, 1966). "Ella – queen of song". Asbury Park Press. p. 7.

- ^ "Spotlight Singles" (PDF). Billboard. No. September 3, 1966. p. 16. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 3, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ "CashBox Record Reviews" (PDF). Cash Box. September 3, 1966. p. 18. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 13, 2022. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- ^ "Single Picks Of The Week" (PDF). Record World (September 3, 1966): 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 11, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ Downbeat (October 9, 1966). "Bob Dylan – pop poet of the dump". Sun-Herald. p. 126.

- ^ McGregor, Craig (October 8, 1966). "Pop Scene". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 19.

- ^ Irvine, Troy (August 28, 1966). "Shades of swing". The Arizona Republic. p. 65.

- ^ a b Gray 2004, p. 149.

- ^ Gray 2004, p. 149-150.

- ^ "Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Songs of All Time". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 1, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ^ Beviglia 2013, p. 155.

- ^ a b c "Just Like a Woman". Bob Dylan's official website. Archived from the original on September 9, 2022. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ Starr 2021, 1445.

- ^ Starr 2021, 2012.

- ^ "Bob Dylan – The Cutting Edge 1965–1966: The Bootleg Series Vol. 12". Bobb Dylan's official website. Archived from the original on February 7, 2016. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ^ Cannon, Geoffrey (January 4, 2022). "The Concert for Bangladesh album review – archive, 1972". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 13, 2022. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ Wilentz 2010.

- ^ Rees & Crampton 1991, p. 323.

- ^ a b c Tobler 1992, p. 160.

- ^ a b c d e f Brown 2000, p. 545.

- ^ Rees & Crampton 1991, p. 324.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Eder, Bruce. "Manfred Mann Biography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ a b Russo 2011, p. 35.

- ^ Miles 2009, p. 130.

- ^ Clapton 2007, pp. 74, 77.

- ^ Russo 2011, p. 37.

- ^ Eder, Bruce. "Michael d'Abo Biography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on February 7, 2022. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ a b Russo 2011, p. 257.

- ^ a b c d McGuinness 1997, p. 1.

- ^ Tamarkin, Jeff (September 7, 2020). "The Mighty Manfred Mann: From 'Do Wah Diddy Diddy' to 'Blinded By the Light'". BestClassicBands. Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ Russo 2011, p. 32.

- ^ a b c Russo 2011, p. 43.

- ^ Russo 2011, p. 54.

- ^ "Names in the News" (PDF). Melody Maker. No. July 23, 1966. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 23, 2022. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ Larkin 2006, p. 850.

- ^ Sounes 2001, p. 217.

- ^ Savage 2015, p. 253.

- ^ a b "Disc Top 50". Disc and Music Echo. No. September 10, 1966. p. 5.

- ^ a b "Melody Maker Pop 50". Melody Maker. No. September 3, 1966. p. 2.

- ^ a b "NME Top 30". New Musical Express. No. September 23, 1966. p. 5.

- ^ a b Hallberg, Eric (1993). Eric Hallberg presenterar Kvällstoppen i P3: Sveriges Radios topplista över veckans 20 mest sålda skivor. Drift Musik. ISBN 978-91-630-2140-4.

- ^ a b Hallberg, Eric; Henningsson, Ulf (1998). Eric Hallberg, Ulf Henningsson presenterar Tio i topp med de utslagna på försök: 1961–74. Premium Publishing. ISBN 978-91-972712-5-7.

- ^ a b "Salgshitlisterne Top 20 - Uge 39". Danske Hitlister. February 19, 1967. Archived from the original on April 14, 2016. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ a b Nyman, Jake (2005). Suomi soi 4: Suuri suomalainen listakirja (in Finnish) (1st ed.). Helsinki: Tammi. p. 201. ISBN 978-951-31-2503-5.

- ^ a b "Bubbling Under The Hot 100" (PDF). Billboard. September 17, 1966. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 23, 2022. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ a b Valentine, Penny. "Manfred, King in Dylan song chart fight" (PDF). Disc and Music Echo. No. July 30, 1966. p. 15. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 23, 2022. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ a b Jopling, Norman; Jones, Peter. "Battle between Manfreds and Jon King over Dylan" (PDF). Record Mirror. No. July 30, 1966. p. 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 23, 2022. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ "Pop Spotlights" (PDF). Billboard. No. August 13, 1966. p. 18. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 8, 2022. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ "CashBox Record Reviews" (PDF). Cash Box. August 13, 1966. p. 24. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- ^ a b Kent, David (2009). Australian Chart Book: Australian Chart Chronicles (1940–2008). Turramurra: Australian Chart Book. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-646-51203-7.

- ^ "Bob Dylan – Just Like a Woman" (in French). Ultratop 50.

- ^ "RPM 100" (PDF). RPM. October 24, 1966. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 6, 2021. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ "Nederlandse Top 40 – week 39, 1966" (in Dutch). Dutch Top 40.

- ^ "Bob Dylan Chart History: Hot 100". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ "Bob Dylan Billboard Singles". AllMusic. Archived from the original on September 13, 2022. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ^ "Cash Box Top 100" (PDF). Cash Box. October 15, 1966. p. 4. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ "100 Top Pops" (PDF). Record World. October 15, 1966. p. 19. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 30, 2021. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ "Go-Set's National Top 40". Go-Set. October 26, 1966.

- ^ Kimberley, C (2000). Zimbabwe: Singles Chart Book. p. 15.

- ^ "SA Charts 1965 – March 1989". Rock.co.za. June 4, 1965. Archived from the original on September 27, 2018. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Cashbox Top 100" (PDF). Cash Box. September 10, 1966. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 26, 2021. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ "100 Top Pops" (PDF). Record World. September 17, 1966. p. 17. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 30, 2021. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

External links

[edit]- Lyrics at Bob Dylan's official website

- 1966 songs

- 1966 singles

- Bob Dylan songs

- Van Morrison songs

- Jeff Buckley songs

- Nina Simone songs

- Joe Cocker songs

- Jonathan King songs

- Songs written by Bob Dylan

- Song recordings produced by Bob Johnston

- Columbia Records singles

- Fontana Records singles

- Manfred Mann songs

- Number-one singles in Sweden

- Country rock songs