Julian Hawthorne

Julian Hawthorne | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | June 22, 1846 Salem, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | July 14, 1934 (aged 88) San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Spouse | Minne Amelung

(m. 1870; died 1925)Edith Garrigues (m. 1925) |

| Children | Hildegarde Hawthorne |

| Parents | Nathaniel Hawthorne Sophia Peabody |

| Signature | |

Julian Hawthorne (June 22, 1846 – July 14, 1934) was an American writer and journalist, the son of novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne and Sophia Peabody. He wrote numerous poems, novels, short stories, mysteries and detective fiction, essays, travel books, biographies, and histories.

Biography

[edit]Birth and childhood

[edit]Julian Hawthorne was the second child[1] of Nathaniel Hawthorne and Sophia Peabody Hawthorne. He was born June 22, 1846, at 14 Mall Street in Salem, Massachusetts.[2] It was shortly after sunrise[3] and his father wrote to his sister:

A small troglodyte made his appearance here at ten minutes to six o'clock, this morning, who claims to be your nephew and the heir of all our wealth and honors. He has dark hair and is no great beauty at present, but is said to be a particularly fine little urchin by everybody who has seen him.[4]

His parents had difficulty choosing a name for eight months. Possible names included George, Arthur, Edward, Horace, Robert, and Lemuel. His father referred to him for some time as "Bundlebreech"[4] or "Black Prince", due to his dark curls and red cheeks.[3] As a boy, Julian was well-behaved and good-natured.[5] He was raised in a loving household, later reflecting: "it was almost appalling to be the subject of such limitless devotion and affection."[6] Julian and his siblings were raised in a positive environment and his parents did not believe in harsh discipline or physical punishment.[7] His father used Julian as an inspiration for the character of Sweet Fern in his children's books A Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys and Tanglewood Tales.[8]

The Hawthorne family eventually lived in Concord, Massachusetts, at a home they called The Wayside. There, Julian attended a school run by Franklin Benjamin Sanborn. The school was coeducational, though Julian's sisters Una and Rose did not attend. His parents disapproved particularly of dances hosted by the school. His mother Sophia wrote: "We entirely disapprove of this commingling of youths and maidens at the electric age in school. I find no end of ill effect from it, and this is why I do not send Una and Rose to your school."[9] Young Julian was close friends with his neighbors at the Orchard House, the Alcott family, and pursued a relationship with the older Abigail May Alcott while he was a young teenager. He later spread the rumor that he inspired the character Laurie in Louisa May Alcott's 1868 novel Little Women, which she denied.[10]

Education and early career

[edit]

Hawthorne entered Harvard College in 1863, but did not graduate. He was tutored privately in German by James Russell Lowell, a professor and writer who encouraged Nathaniel Hawthorne's work.[11] It was during his freshman year at Harvard that he learned of his father's death, coincidentally the same day he was initiated into a fraternity. Years later, he wrote of the incident:

I was initiated into a college secret society—a couple of hours of grotesque and good-humored rodomontade and horseplay, in which I cooperated as in a kind of pleasant nightmare, confident, even when branded with a red-hot iron or doused head-over heels in boiling oil, that it would come out all right. The neophyte is effectively blindfolded during the proceedings, and at last, still sightless, I was led down flights of steps into a silent crypt and helped into a coffin, where I was to stay until the Resurrection ... Thus it was that just as my father passed from this earth, I was lying in a coffin during my initiation into Delta Kappa Epsilon.[12]

After his father's death, Hawthorne considered himself head of the household, quit Harvard, and abandoned his interest in joining the army. He took over his father's study in the tower of The Wayside and, his mother recalled, the difficult time "made a man of him, for he feels all the care of me and his sisters".[13]

Hawthorne studied civil engineering in the United States and Germany, was engineer in the New York City Dock Department under General McClellan (1870–72), spent 10 years abroad, and met Minne Amelung. She and Hawthorne were married in Orange, New Jersey, on November 15, 1870.[14]

Writing career

[edit]While in Europe Hawthorne wrote several novels: Bressant (1873); Idolatry (1874); Garth (1874); Archibald Malmaison (1879); and Sebastian Strome (1880). Hawthorne prepared an edition of his father's unfinished work Dr. Grimshawe's Secret (1883). His sister Rose, upon hearing of the book's announcement, had not known about the fragment and originally thought her brother was guilty of forgery or a hoax. She published the accusation in the New York Tribune on August 16, 1882, and claimed, "No such unprinted work has been in existence ... It cannot be truthfully published as anything but an experimental fragment". He defended himself from the charge, however, and eventually dedicated the book to his sister and her husband George Parsons Lathrop.[15]

In July 1883, Hawthorne was invited to participate as a lecturer at the Concord School of Philosophy by his former neighbors Amos Bronson Alcott and Sanborn. Hawthorne presented a version of a paper he had recently published, "Agnosticism in American Fiction", which criticized the emerging American Realism movement and took aim particularly at William Dean Howells and Henry James, whose works Hawthorne believed represented "life and humanity not in their loftier, but in their lesser manifestations". Hawthorne returned the following summer to present "Emerson as an American".[16]

Hawthorne published the first of two books about his parents, Nathaniel Hawthorne and His Wife, in 1884–85. The younger Hawthorne also wrote a critique of his father's novel The Scarlet Letter that was published in The Atlantic Monthly in April 1886.

Julian Hawthorne published an article in the October 24, 1886, issue of the New York World based on a long interview with James Russell Lowell, who had recently served as a U.S. diplomat to England. In the article, titled "Lowell in a Chatty Mood", Hawthorne reported that Lowell offered various negative comments on British royalty and politicians, like saying that the Prince of Wales was "immensely fat". Lowell angrily complained that the article made him seem like "a toothless old babbler".[11]

Between 1887 and 1888, Hawthorne published a series of detective fiction novels following the character Inspector Barnes, including The Great Bank Robbery, An American Penman, A Tragic Mystery, Section 558, and Another's Crime.[17] The character was strongly based on Hawthorne's friend and real-life detective Thomas F. Byrnes. In 1889 there were reports that Hawthorne was one of several writers who had, under the name of "Arthur Richmond", published in the North American Review devastating attacks on President Grover Cleveland and other leading Americans. Hawthorne denied the reports.

In 1895, Hawthorne was one of several authors and journalists wooed to work for William Randolph Hearst and his syndicate of newspapers, along with writers Stephen Crane, Richard Harding Davis, Murat Halstead, Alfred Henry Lewis, Edgar Wilson Nye, Julian Ralph, and Edgar Saltus.[18] Hawthorne published a second book about his father, Hawthorne and His Circle, in 1903. In it, he responded to a remark from his father's friend Herman Melville that Nathaniel Hawthorne had a "secret". Julian dismissed this, claiming Melville was inclined to think so only because "there were many secrets untold in his own career", causing much speculation.[19] As he wrote of his meeting with Melville,

When I was in New York, in 1884, I met him, looking pale, sombre, nervous, but little touched by age. He died a few years later. He conceived the highest admiration for my father's genius, and a deep affection for him personally; but he told me, during our talk, that he was convinced that there was some secret in my father's life which had never been revealed, and which accounted for the gloomy passages in his books. It was characteristic in him to imagine so; there were many secrets untold in his own career. But there were few honester or more lovable men than Herman Melville.[20]

As a journalist, he reported on the Indian Famine for Cosmopolitan magazine and the Spanish–American War for the New York Journal.

Fraud and imprisonment

[edit]

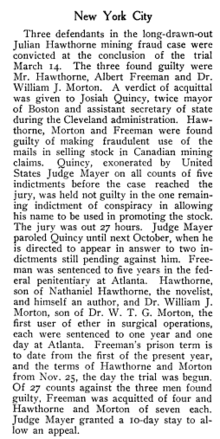

In 1908, Hawthorne's old Harvard friend William J. Morton (a physician) invited Hawthorne to join in promoting some newly created mining companies in Ontario, Canada. Hawthorne made his writing and his family name central to the stock-selling campaigns. After complaints from shareholders, both Morton and Hawthorne were tried in New York City for mail fraud, and convicted in 1913.[21] Hawthorne was able to sell some three and a half million shares of stock in a nonexistent silver mine and served one year in the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary.[22]

Upon his release from prison, he wrote The Subterranean Brotherhood (1914), a nonfiction work calling for an immediate end to incarceration of criminals.[23] Hawthorne argued, based on his own experience, that incarceration was inhumane and should be replaced by moral suasion. Of the fraud with which he was charged he always maintained his innocence.

Final years and death

[edit]After his release from prison on October 15, 1913, Hawthorne returned to work as a journalist in Boston for the Boston American, for which he covered baseball spring training and interviewed George Stallings and Babe Ruth.[24] He resigned from the publication in November and moved to California, where he contributed to publications like the Los Angeles Herald and pitched movie screenplays which were never produced. He also shared a home with his lover Edith Garrigues.[25] His wife Minne was living with family in Redding, Connecticut. After her death on June 25, 1925, Hawthorne and Garrigues officially married on July 6 after nearly two decades as a couple.[26] In the summer of 1933, Hawthorne suffered from a flu, after which he was never fully healthy again. He suffered two heart attacks before dying on July 14, 1934. His funeral was private and, after his body was cremated, his ashes were scattered along Newport Beach, California.[27]

Works

[edit]- Bressant (1873)

- Idolatry: A Romance (1874)

- Garth (1874)

- Saxon Studies (1876)

- Archibald Malmaison (1879)

- Sebastian Strome (1880)

- Dust (1882)

- Beatrix Randolph (1883)

- Nathaniel Hawthorne and His Wife (1884)

- The Great Bank Robbery (1887)

- An American Penman (1887)

- A Tragic Mystery (1887)

- Section 558 (1888)

- Another's Crime (1888)

- The Golden Fleece (1892)

- An American Monte Cristo (1893)

- American Literature: A Text Book for the Use of Schools and Colleges (1896, with Leonard Lemmon)

- A Fool of Nature (1896)

- One of Those Coincidences and Ten Other Stories (1899)

- Hawthorne and His Circle (1903)

- The Subterranean Brotherhood (1914)

- The Cosmic Courtship (1917)

- A Goth From Boston (1919)

- Sara Was Judith (1920)

- Rumpty-Dudget's Tower: A Fairy Tale (1924)

- The Memoirs of Julian Hawthorne (1938; edited by Edith Garrigues Hawthorne and published posthumously)[28]

References

[edit]- ^ McFarland, Philip. Hawthorne in Concord. New York: Grove Press, 2004: 132. ISBN 0-8021-1776-7

- ^ Wright, John Hardy. Hawthorne's Haunts in New England. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2008: 47. ISBN 978-1-59629-425-7

- ^ a b Wineapple, Brenda. Hawthorne: A Life. Random House: New York, 2003: 197. ISBN 0-8129-7291-0

- ^ a b Miller, Edwin Haviland. Salem Is My Dwelling Place: A Life of Nathaniel Hawthorne. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1991: 259. ISBN 0-87745-332-2

- ^ Wineapple, Brenda. Hawthorne: A Life. Random House: New York, 2003: 200. ISBN 0-8129-7291-0

- ^ McFarland, Philip. Hawthorne in Concord. New York: Grove Press, 2004: 184. ISBN 0-8021-1776-7

- ^ Miller, Peggy J. and Grace E. Cho. Self-Esteem in Time and Place: How American Families Imagine, Enact, and Personalize a Cultural Ideal. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2018: 7. ISBN 9780199959723

- ^ Scharnhorst, Gary. Julian Hawthorne: The Life of a Prodigal Son. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2014: 13. ISBN 978-0-252-03834-1

- ^ Mellow, James R. Nathaniel Hawthorne in His Times. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 190: 537. ISBN 0-395-27602-0

- ^ Scharnhorst, Gary. Julian Hawthorne: The Life of a Prodigal Son. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2014: 34. ISBN 978-0-252-03834-1

- ^ a b Duberman, Martin. James Russell Lowell. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1966: 488.

- ^ Matthews, Jack (August 15, 2010). "Nathaniel Hawthorne's Untold Tale". The Chronicle Review. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

- ^ Scharnhorst, Gary. Julian Hawthorne: The Life of a Prodigal Son. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2014: 42. ISBN 978-0-252-03834-1

- ^ Scharnhorst, Gary. Julian Hawthorne: The Life of a Prodigal Son. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2014: 55. ISBN 978-0-252-03834-1

- ^ Valenti, Patricia Dunlavy. To Myself a Stranger: A Biography of Rose Hawthorne Lathrop. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1991: 67–68. ISBN 978-0-8071-2473-4

- ^ Scharnhorst, Gary. Julian Hawthorne: The Life of a Prodigal Son. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2014: 111. ISBN 978-0-252-03834-1

- ^ Panek, LeRoy Lad. The Origins of the American Detective Story. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc.: 2006: 21. ISBN 978-0-7864-2776-5

- ^ Procter, Ben. William Randolph Hearst: The Early Years, 1863-1910. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998: 81. ISBN 0-19-511277-6

- ^ Miller, Edwin Haviland. Salem Is My Dwelling Place: A Life of Nathaniel Hawthorne. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1991: 35. ISBN 0-87745-332-2; Hawthorne, Julian. Hawthorne and His Circle. New York and London: Harper & Brothers, 1903:33.

- ^ Hawthorne, Julian. Hawthorne and His Circle. New York and London: Harper & Brothers, 1903:33.

- ^ Julian Hawthorne

- ^ Nelson, Randy F. The Almanac of American Letters. Los Altos, California: William Kaufmann, Inc., 1981: 259. ISBN 0-86576-008-X

- ^ Dirda, Michael (July 23, 2014). "'Julian Hawthorne: The Life of a Prodigal Son,' by Gary Scharnhorst". Washington Post. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ Scharnhorst, Gary. Julian Hawthorne: The Life of a Prodigal Son. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2014: 200–201. ISBN 978-0-252-03834-1

- ^ Scharnhorst, Gary. Julian Hawthorne: The Life of a Prodigal Son. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2014: 203–204. ISBN 978-0-252-03834-1

- ^ Scharnhorst, Gary. Julian Hawthorne: The Life of a Prodigal Son. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2014: 209. ISBN 978-0-252-03834-1

- ^ Scharnhorst, Gary. Julian Hawthorne: The Life of a Prodigal Son. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2014: 212–213. ISBN 978-0-252-03834-1

- ^ "Books: Hawthorne's Line". Time. April 25, 1938. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

Further reading

[edit]- Plazak, Dan. A Hole in the Ground with a Liar at the Top: Fraud and Deceit in the Golden Age of American Mining. University of Utah Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-87480-840-7 — includes a chapter on Julian Hawthorne, concentrating on his mine promotion activities

- Scharnhorst, Gary. "'I didn't like his books': Julian Hawthorne on Whitman". Walt Whitman Quarterly Review 26(3) (2009), pp. 151-156.

External links

[edit]- Works by Julian Hawthorne at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Julian Hawthorne at the Internet Archive

- Works by Julian Hawthorne at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Guide to the Hawthorne Family Papers at The Bancroft Library

- Harvard College alumni

- 19th-century American novelists

- 20th-century American novelists

- American male novelists

- American mystery writers

- American travel writers

- American male biographers

- 19th-century American historians

- American male journalists

- American people convicted of fraud

- 1846 births

- 1934 deaths

- Journalists from Boston

- Writers from New Rochelle, New York

- American male short story writers

- 20th-century American poets

- American male poets

- 20th-century American biographers

- American male essayists

- 19th-century American short story writers

- 20th-century American short story writers

- 19th-century American essayists

- 20th-century American essayists

- 19th-century American male writers

- Journalists from New York (state)

- 20th-century American male writers

- Novelists from New York (state)

- Novelists from Massachusetts

- Historians from New York (state)