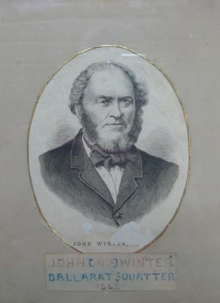

Jock Winter

John Winter (c. 1800 – August 1875), familiarly known as Jock Winter, was a Scottish squatter and pastoralist in Ballarat, Victoria. Winter emigrated to Australia in 1841. He became a wealthy shepherd at Buninyong, buying a run from Henry Anderson and renaming it Bonshaw for his wife, daughter of the laird of Bonshaw. One of his employees struck gold in 1850.

Winter later sold Bonshaw and earned a great profit. After his wife's death, he remarried and lived frugally on a secluded house at the top of Stuart St, said to be the richest man in Ballarat. The suburb of Winter Valley and a Redan street is named for Winter, and Bonshaw his estate. His third son was politician William Winter-Irving.

Biography

[edit]John Winter was born in Lauder, Scotland. After attending the village school, he was apprenticed as a butcher in Edinburgh before working as a stockbroker in the Scottish Highlands. In 1825, Winter married Janet Margaret (née Irving). She was the daughter of the laird of the Barony of Bonshaw. Winter worked as a butcher for sixteen years and earned a considerable amount of money buying "Queen of Spain bonds" after the First Carlist War.[1]

In 1841 Winter emigrated to Australia. Impressed by the beef in John O'Shanassy's shop, he became a shepherd in Buninyong where it was raised. He was paid his wages in sheep after his employer got into difficulties and his flock tripled. He bought a run from Henry Anderson and George Russel, originally named Waverley Park, but named it Bonshaw after his wife's birthplace. Kemp, a shepherd in his employ, first discovered gold in the colony between Winter's Flat and Buninyong Rd. in 1850. By this point, he had a large tract of country and around 20,000 sheep and made "enormous profit" selling to diggers and butchers.[1]

From 1852 to 1854 Winter earned a great amount of money and bought sheep stations for his two sons. In his well-known selling of Bonshaw, he earned £23,000 for a portion of the 640 acres, which he purchased at £1 per acre, and obtained £50,000 from the Winters Freehold Company for 1359 acres. He purchased a great amount of land from nearby colonies. After his first wife's death, he remarried and lived frugally on a secluded house at the top of Stuart St., reputed to be a millionaire. He died in August 1875.[1][2] An obituary in the Melbourne Leader said of him: "Jock Winter has retired from this world of wool and weariness, money and muddle [...] Of Mr. Winter it might fairly be said that he never said a wise thing and never did a foolish one."[3] He was said to be the richest man in Ballarat.[4][5]

While an 1875 obituary says he was born 1803,[1] the website for the William-Irving clan gives his birth at 30 June 1794, to Thomas and Betty Winter (née Yellowlees). It dates his first marriage 26 April 1825, his emigration 17 June 1841, and says he had six sons and three daughters by his first wife and three sons and one daughter by his second wife, Mary Cowie, who he married in 1850. The website also gives his date of death at 12 August 1875.[6]

Legacy

[edit]Winter had many children who all possessed stations of their own, including two sons from his second wife.[1] His third son was politician William Winter-Irving.[7] Winter built the Lauderdale Homestead (7 Prince Street, Alfredton), designed by architect J. A. Doane, in 1863. It is listed on the Victorian Heritage Register and the National Trust of Australia.[8][9] In The Courier in 2015, Winter "was said to be a pioneer who gave generously to those less fortunate". The suburb of Winter Valley and Winter St., Redan is named for Winter,[10][11] while Bonshaw is named for his wife's birthplace.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "SUDDEN DEATH OF MR. JOHN WINTER". Gippsland Times. 31 August 1875. p. 4. Retrieved 18 December 2022 – via Trove.

- ^ "BALLARAT". Hamilton Spectator. 13 July 1878. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ "INTERCOLONIAL". Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser. 18 September 1875. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ Strange, A.W. (1982). Ballarat: The Formative Years. Ballarat, Victoria: B. & B. Strange. p. 43. ISBN 9780959680232.

- ^ Newton, Janice (September 2016). "Rural Autochthony? The Rejection of an Aboriginal Placename in Ballarat, Victoria, Australia". Cultural Studies Review. 22 (2). University of Technology Sydney: UTS ePress. doi:10.5130/csr.v22i2.4478.

- ^ "Our Forefathers". Clan Winter-Irving. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ Mennell, Philip (1892). . The Dictionary of Australasian Biography. London: Hutchinson & Co – via Wikisource.

- ^ "Lauderdale Homestead". Victorian Heritage Database. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ Sobey, Emily (2 November 2012). "Historic Alfredton home on the market". The Courier. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ "City of Ballarat Roads & Open Space Index" (PDF). ballarat.vic.gov.au. 1998. Revised 21 January 2017. pp. 4, 53. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Cunningham, Melissa (17 June 2015). "'Mullawallah' dropped as name for new suburb". The Courier. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

General sources

[edit]Winters, W.B. (1980) [1887]. History of Ballarat, from the first pastoral settlement to the present time (2nd ed.). Carlton, Victoria: Queensberry Hill Press.

Strange, A.W. (1982). Ballarat: The Formative Years. Ballarat, Victoria: B. & B. Strange. ISBN 9780959680232.

External links

[edit]- Jock Winter at the Redanopedia

- Ancestry articles at Clan Winter-Irving