James Skinner (East India Company officer)

James Skinner | |

|---|---|

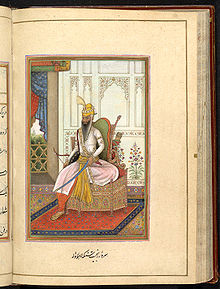

James Skinner, from his Tazkirat al-Umara (Account of the Nobles of Delhi and its neighbourhood) | |

| Nickname(s) | Sikandar Sahib |

| Born | 1778 Calcutta, Bengal Presidency |

| Died | 4 December 1841 (aged 62–63) Hansi, Bengal Presidency |

| Service | Maratha Army (1796–1803) Bengal Army (1803–1841) |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Unit | Skinner's Horse |

| Battles / wars | Second Anglo-Maratha War Third Anglo-Maratha War Battle of Malpura |

| Signature |  |

Colonel James Skinner (1778 – 4 December 1841)[1] was an Anglo-Indian military adventurer and soldier of the East India Company of British India. Prior to this he also served briefly as a mercenary in the Maratha Army. He became known as Sikandar Sahib later in life and is most known for two cavalry regiments he raised for the British at Hansi in 1803, known as 1st Skinner's Horse and 3rd Skinner's Horse (formerly 2nd Skinner's Horse), which are still units of the Indian Army.[2]

Born to a Scottish father and an Indian mother from the Bhojpur region, he was fluent in Persian, the court and intellectual language of India in his day.[3] Skinner composed several works in the language, including an extensively illustrated manuscript Kitāb-i Tashrīḥ al-Aqvām (History of the Origin and Distinguishing Marks of the Different Castes of India), now held by the Library of Congress.[4][5]

He is sometimes referred to as the "father of the Indian cavalry".[6] The historian Mildred Archer said: "Among military adventurers who have served in India, none was more dashing than the half-Indian leader of the famous Irregular Cavalry Corps known as Skinner's Horse."[7]

Early life

[edit]Skinner was born in 1778 in Calcutta (now Kolkata), India. His father was Lieutenant-Colonel Hercules Skinner (c. 1735 – 12 July 1803),[1] an officer in the East India Company Army of Scottish origin. Skinner claimed that his mother Jeany[1] was an Indian aristocrat, daughter of a Rajput zamindar from the "Bojepoor country" (standard spelling is Bhojpuri) around Bejaghur in what was then part of Benares district and later part of Mirzapur district.[8][9] She was taken prisoner at the age of fourteen by Maharaja Chait Singh of Benares State, and later came under the care of his father, then an ensign, who treated her with much regard. Subsequently, they had seven children, two girls and five boys, Joseph, James, Hercules, Alexander, Thomas, Louisa and Elizabeth.[5][10][11] When he was 12 years old, his mother Jeany committed suicide because her daughters were sent to a school for children of mixed heritage.[1]

Skinner was first educated at an English school in Calcutta, and then in 1794 sent to a boarding school.[1][12]

Career

[edit]His father originally apprenticed him to a printer in Calcutta but hating the life he ran away after three days.[13] Because of his Indian heritage, Skinner was unable to serve as an officer in the East India Company army[14] and, at the age of sixteen, he entered the Maratha army as an ensign under Benoît de Boigne,[15] the French commander of Maharaja Scindia's forces of Gwalior State. Boigne was impressed by his family ancestry, Skinners having served William the Conqueror in the 11th century. Once taken in, Skinner soon showed military talent.[16] He remained in the same service under Pierre Cuillier-Perron, who became commander-in-chief of Sindhia's army after Boigne's retirement, until 1803,[15] when, on the outbreak of the Second Anglo-Maratha War, all Anglo-Indians were dismissed from Maratha service.[14]

Eventually, he joined the Bengal Army of the East India Company where Lord Lake had become Commander-in-Chief of British India in 1801. Subsequently, on 23 February 1803, Skinner raised a regiment of irregular cavalry called "Skinner's Horse" or the "Yellow Boys"[15] because of the colour of their uniform.[5] Later it became a famous regiment of light cavalry in the British Indian Army[15] and still exists today as part of the Indian Army. Commanding his regiment of irregular cavalry in 1805 he was present at the Siege of Bharatpur and took part in the Pindari War (1817–18).[1] For his services he was granted a jagir of Hansi (Hisar district, Haryana), yielding Rs 20,000 a year.[15]

In 1828, Skinner was finally given the rank of lieutenant-colonel in the British service, and his brother Robert that of major. Later James became a colonel,[16] having already been appointed Companion of the Order of the Bath on 26 December 1826.[17]

Other works

[edit]Skinner had an intimate knowledge of the characters of the people of India, and his advice was highly valued by successive governor-generals and commanders-in-chief.[15] He commissioned paintings in the Company style on a large scale. Additionally, Skinner wrote a volume of memoirs in Persian of his military expeditions, titled Tazkirat al-umara which contained family biographies, of princely families in the Sikh and Rajput territories and 37 portraits of their current representatives.[18] It was first translated from the original Persian by James Fraser.[citation needed]

St. James' Church

[edit]

St. James' Church, also known as Skinner's Church, was commissioned by Skinner after he had vowed while lying wounded on the battlefield of Uniara in 1800,[10] to build one if he survived. It was built at his own expense and at a cost of Rs 95,000. Designed by Major Robert Smith it was built between 1826–36 to a cruciform plan, with three porticoed porches and a central octagonal dome.[19] It was consecrated on 21 November 1836 by the Right Reverend Daniel Wilson, the Bishop of Calcutta, making it the oldest church in Delhi.[16] Skinner is also reported to have built a temple and a mosque, though details of them are unknown.

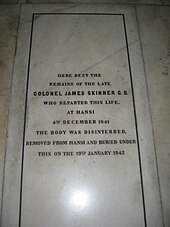

He had also lived at Jahaj kothi in Hisar after the defeat of Irish mercenary adventurer George Thomas (c. 1756 – 22 August 1802). Skinner, while serving Maratha, had earlier fought against George Thomas. Skinner died at Hansi (in Hisar district, Haryana), on 4 December 1841, at the age of 64. He was first buried in the Cantonment Burial Ground at Hansi and after a period of 40 days was disinterred, and his coffin brought to Delhi, escorted by 200 men of Skinner's Horse. Subsequently, he was buried in Skinner's Church on 19 January 1842 in a vault of white marble immediately below the Communion table.[16][20]

Personal life

[edit]

All of his three sisters married gentlemen in the East India Company's service, while his elder brother, David, went to sea, and his younger brother, Robert, also became a soldier. Emily Eden, sister of Governor-General George Auckland records in 1838 that Major Robert Skinner, was "the same sort of melodramatic character" as his elder brother and made a tragic end. Suspecting his wife of infidelity he killed several of his servants and then shot himself.[21]

It is said that James Skinner had fourteen wives and many children, one of whom was Mrs Wagentreiber, who managed to escape the Indian Rebellion of 1857 because he was greatly revered by the Indian Army regiments.[22] His eldest son, Hercules Skinner, was commissioned into the Nizam's Contingent; another son, James Skinner, became an officer in Skinner's Horse and was killed in action during the First Anglo-Afghan War. Many of his family members and their descendants are buried in Skinner's family plot, north of St. James' Church, Delhi.[23]

Skinner was a close friend of William Fraser, and was buried next to him in Skinner’s Church,[23] and of his brother James Baillie Fraser, the author of Military Memoirs of Col. James Skinner (1851).[24]

Descendants

[edit]A grandson is mentioned, also called James Skinner, who erected a statue of Queen Victoria upon her death, at his own expense at Chandni Chowk, Delhi.[25]

In 1960, Lt-Col Michael Skinner, a great-great-grandson, took command of Skinner's Horse, and was the first Skinner to command the Skinner's Horse regiment since its founder's death.[26] In 2003, when a special service was held at St. James' Church, Delhi to commemorate 200 years of Skinner's Horse, the cavalry regiment raised by Skinner in 1803, amongst those present was Patricia Sedwards (née Skinner), niece of Lt-Col Michael Skinner.[27]

In popular culture

[edit]Vikram Chandra's debut novel, Red Earth and Pouring Rain (1995), was inspired by the autobiography of James Skinner. In 1979, Philip Mason published Skinner of Skinner’s Horse: a fictional portrait, based upon Skinner's life.

Works

[edit]- Skinner, James (1825). Kitab-i tasrih al-aqvam [History of the origin and distinguishing marks of the different Castes of India] (in Persian).

- ——————— (1830). Tazkirat al-umara [Account of the Nobles of Delhi and its neighbourhood] (in Persian).

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Wheeler 2004.

- ^ "'Dhana/Colonel Skinner's Farm', with Colonel James Skinner CB riding in an open carriage, 1828". National Army Museum. Archived from the original on 18 December 2010.

- ^ Dalrymple, William (2021). The Company Quartet. Bloomsbury. p. 89. ISBN 9781526644909.

- ^ "Manuscript Book on History of Castes in India" Rosenwald Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, by James S. Collins of Pennsylvania

- ^ a b c 1st Horse / Skinner’s Horse Global Security."Eight hundred men on horses offered their services on one condition wished to be led by James Skinner."

- ^ Pearse, Colonel H.W (1907). "Fathers of the Indian Cavalry". The Cavalry Journal. 2: 287.

- ^ Archer, Mildred (1960). "The Two Worlds of Colonel Skinner, 1778-1841". HistoryToday. 10 (9): 608–615.

- ^ Dalrymple, William (2009). The Last Mughal The Fall of Delhi, 1857. Bloomsbury. p. 72. ISBN 9781408806883.

- ^ Holman, Dennis (1961). Sikander Sahib; Life Of Colonel James Skinner 1778 - 1841. Heinemann. p. 5.

- ^ a b Now St. James's Church in Kashmere Gate is the oldest church in Delhi The Hindu, Monday, 5 March 2007.

- ^ MEMORIES... Army Children Archive (TACA).Sikander Sahib: The Life of Colonel James Skinner, 1778-1841, London, 1961, pp.213-14.

- ^ Indian cavalry - 1st Skinners - History britishempire.co.uk

- ^ "Military Memoir of Lieut.-Colonel James Skinner"

- ^ a b Dalrymple, William (1993). City of Djinns: A Year in Delhi. HarperCollinsPublishers. ISBN 9780002157254.

- ^ a b c d e f Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 192.

- ^ a b c d Skinner's Tomb, St. Jame's Church, Delhi Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine British Library.

- ^ "No. 18319". The London Gazette. 2 January 1827. p. 2.

- ^ "An illustration of Maharaja Ranjit Singh". British Library. Archived from the original on 6 March 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ No.3. Skinner's Church, Delhi. Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine British Library.

- ^ St Jame's Church, with tomb of William Fraser Archived 10 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine British Library.

- ^ Chapter XII, "Up the Country" Emily Eden, Delhi, 20 February 1838

- ^ "Cemetery Details - St. James' Church". Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- ^ a b Herbert Compton A Particular Account of the European Military Adventurers of Hindustan (Unwin, 1893), pp. 396–397

- ^ Falk, Toby (December 1988). "The Fraser Company Drawings". RSA Journal. 137 (5389): 27–37. JSTOR 41374777.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Notes # 16 Indigenous modernities: negotiating architecture and urbanism, by Jyoti Hosagrahar. Published by Routledge, 2005. ISBN 0-415-32375-4. Page 207.

- ^ Lt-Col Michael Skinner The Independent (London), 17 May 1999.

- ^ Skinner's Horse... the memory lives on The Hindu, Monday, 24 November 2003.

Further reading

[edit]- Archer, Mildred (1982). Between Battles: The Album of Colonel James Skinner. London: Al-Falak and Scorpio. ISBN 9780905906348.

- Fraser, James Baillie (1851). Military Memoir of Lieut.-Col. James Skinner, C.B. Vol. I. London: Smith, Elder and Co. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139199148. ISBN 9781139199148.

- Fraser, James Baillie (1851). Military Memoir of Lieut.-Col. James Skinner, C.B. Vol. II. London: Smith, Elder and Co. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139199155. ISBN 9781139199155.

- Holman, Dennis (1961). Sikander Sahib: The Life of Colonel James Skinner, 1778–1841. London: Heinemann. ISBN 9780598460745.

- Mason, Philip (1986). "A meditation on the life of Colonel James Skinner". In Frykenberg, Robert Eric (ed.). Delhi Through the Ages: Essays in Urban History, Culture, and Society. Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 278–286. ISBN 978-0195617283.

- Wheeler, Stephen Edward (1885–1900). . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Wheeler, Stephen Edward (2004). "Skinner, James (1778–1841)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/25676. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)