James Glencairn Burns

James Glencairn Burns | |

|---|---|

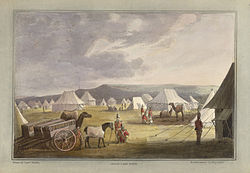

Lieutenant James Glencairn Burns in 1838 | |

| Born | 12 August 1794[1] |

| Died | 1865[1] |

| Occupation | East India Company |

| Spouse(s) | Sarah Robinson; Mary Becket |

| Children | Sarah, Robert, Jean, Isabella and Ann[2] |

| Parent(s) | Robert Burns Jean Armour[1] |

James Glencairn Burns (1794–1865) was the fourth son and eighth child born to the poet Robert Burns and his wife Jean Armour.[1] James was born at their home in Mill Brae Street, now Burns Street in Dumfries on 12 August 1794.[1] His first and middle name was added in honour of James Cunningham, 14th Earl of Glencairn, Robert's friend, patron and mentor.[2]

Life and family

[edit]James was born at the family home in what is now Burns Street, Dumfries, on 12 August 1794 as recorded in the family register in the Burns family Bible. The family had moved from Ellisland Farm to the 'Stinking Vennel' in Dumfries on 11 November 1791.[3] In late spring 1793 they made the move to a larger house in Millhole Brae (Burns Street), where James's mother lived for the remainder of her life following his father's death in 1796.[4]

James's siblings were Robert Burns Junior (b. 3 March 1788); Jean (b. 3 March 1788); William Nicol (b. 9 April 1791); Elizabeth Riddell (b. 21 November 1792); Francis Wallace (b. 1789) and Maxwell (b. 25 July 1796). Short lived un-named twin girls (b. 3 March 1788).[5]

Education

[edit]Educated at Dumfries Grammar School, James later studied at a Charity school, The Bluecoat School, Christ's Hospital, Horsham.[6] His admission papers to Christ's Hospital survive and reveal that he was accepted because his father had died about three years before. James went to Christ's Hospital from 1802 to 1809, entering at the age of eight, "his mother having been left with a family of four children and without sufficient means for their support". The admission papers to the charity school had to be certified by a minister, along with a completed petition by the parent and a copy of the baptism entry and marriage entry of the parents.[7]

Career

[edit]

Once James had completed his education at Christ's Hospital, he had to be 'discharged' and in James's case this was carried out by Sir James Shaw. James Shaw, when Sheriff of London, arranged for James to become a cadet in India in the military service of the Honourable East India Company.[8] James attended the East India Company Military Seminary, joining in 1815 the Bengal Presidency's army as an Ensign (Second Lieutenant). He had achieved the rank of Captain by 28 June 1817, attached to the Third Native Infantry Regiment as a Deputy Assistant Commissary.[9]

A rare letter written by James's mother in 1804, probably to Maria Riddell, was found by chance in New York in 2009 that records this assistance from James Shaw, a relative, to Francis Wallace as well.[8] Shaw was born at Riccarton in Ayrshire, the son of John Shaw, whose family had farmed the area of Mosshead for over 300 years. Shaw was a nephew of Gilbert Burns through his wife Jean Breckenridge.[10]

The Marchioness of Hastings and Sir John Reid also assisted James's career.[11] James joined the East India Company's Service as a cadet aged 16 in the 15th Bengal Native Infantry.[6] and rose to reach the rank of Major.

Sir James also wrote a testimonial as to Lieutenant James's abilities in languages as part of a wider report on his character and then sent this to Lady Hastings, wife of the then Governor General of India in 1816. James hoped to become an interpreter to the battalion or even to gain a position in the Commissariat, however in a letter from Jean Armour to Lady Hastings she states "A few days ago I had a letter from him dated in April in which he regrets deeply your Ladyship's leaving India – to this he ascribes his having been forgotten – and as the vacancies in the department are filled up, he has lost his hopes of advancement. As he is naturally of an eager disposition he feels his disappointment very keenly".[12] Another letter to Lady Hastings on 16 July 1818 was written in a more positive tone, indicating that Jean had met with the marchioness in Dumfries and suggesting that matters had been put right.[13]

Indeed in 1818 he was promoted to the Indian Commissariat and was able to assist his mother to the tune of £150 per year that was a very welcome assistance. Eventually he was unable to afford this and his brother William took over and gave the same sum per annum.[14]

James was involved in the third Mahratta War and the Nepal War as well as the capture of the Lamba Fort.[1] Following a visit home to Scotland, in 1833 he returned to India and was appointed Judge and Collector at Cahar in southern Assam.[2][6]

Marriage and family

[edit]James first married Sarah Robinson, daughter of James Robinson of Sunderland,[15] in Meerut, in 1818. They had children Jeanie Isabella and Robert who died in childhood and a daughter Sarah, born in Neemuch on 2 November 1821.[16] Sarah Robinson Burns, James's wife, died in 1821 at Neemuch, India, just three years after their 1818 marriage, shortly after Sarah Elizabeth Maitland Tombs, their second daughter, was born.[2] Previous offspring, as stated, were a son, Robert Shaw and a daughter, Jean Isabella[11] who died in their infancy,[2] Jean on 5 June 1823 aged four and Robert on 11 December 1821 aged only eighteen months.[11]

A daughter Ann or Annie was born to James and his second wife Mary Becket on 21 September 1830 at Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India.[17][2] She was the daughter of Captain Beckett of Enfield.[15] Mary died, aged 52, at Gravesend, 13 November 1844.[18] Sarah and Annie are buried under an ornate headstone at Charlton Kings churchyard in Cheltenham.[19]

Retirement

[edit]Retiring in 1839 James moved from India and lived in London for four years. His second wife Mary Becket, who he had married in 1828 at Nasirabad in India,[2] died on 13 November 1844 aged 54.[6][11] and then to Berkely Street in Cheltenham where he lived with his brother, the widower William Nicol Burns and his daughters Annie and Sarah.[2] In 1855 James was appointed brevet Lieutenant-Colonel.[6] This was a warrant that gave a commissioned officer a higher rank, as a reward for meritorious conduct or gallantry, but may not necessarily confer the precedence, authority, or pay of the real rank. James taught Hindustani and was involved in amateur theatricals.[1]

On 6 August 1844 a 'Burns Festival' attended by around 80,000 people took place at Ayr and the Burns Monument at Alloway with James Glencairn, William Nicol and Robert Burns Junior in attendance, the three surviving sons of the poet.[20] Their aunt Isabella Burns was also in attendance. They sadly refused to meet Robert, their nephew, their father's natural son by Elizabeth 'Betty' Burns at the festival.[21]

On 15 August 1844 James and his brother William Nicol were entertained in the Kings Arms Hotel, High Street, Irvine by the Irvine Burns Club.[22]

In 1831 James was a guest of Sir Walter Scott at Abbotsford House[6] and he visited his mother in 1834 and a few times in Dumfries, where his daughter Sarah lived for twelve happy years with her grandmother Jean,[11] James paying a small allowance for her 'room and board'.[16] Later Sarah rejoined her father, living with her stepmother and half-sister Annie.[23]

Paintings and photographs exist of James Glencairn, one taken by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson calotype, 1843-1848.[24]

James had been in poor health for some years and suffered from rheumatism.[15] His death was hastened by a fall on the stairs at his home.[15] died in Cheltenham on 18 November 1865 and was buried in the Burns Mausoleum in the churchyard of St Michael's in Dumfries, Scotland.[2]

His oldest brother Robert Burns Junior married Anne Sherwood when he was 22 and had a daughter, Eliza, who went out to India with James Glencairn Burns and married a Dr Everitt of the East India Company, dying in 1878.

Elizabeth 'Betty' Burns had a son named James Glencairn Thomson. 'Betty' was excluded from the 1844 festival[25] and, as stated, her son Robert Thomson was rejected upon trying to greet his father's sons, his uncles, at the Ayr Festival.[21]

James Glencairn, together with his brothers William Nicol and Robert junior, was made an Honorary Member of the Lodge St James on 9 August 1844 at a meeting held in the old Cross Keys Inn at Tarbolton.[26]

Correspondence

[edit]Robert Burns, James's father, wrote to Mrs Frances Dunlop in September 1794 saying "Apropos, the other day, Mrs Burns presented me with my fourth son, whom I have christened James Glencairn; in grateful memory of my lamented patron. I shall make all my children's names, altars of gratitude."[1]

On 29 October 1794 Robert wrote again to Frances Dunlop "I would without hesitation have crossed the country to wait on you, but for one circumstance – a week ago I gave my little James the small-pox & he is just beginning to sicken. In the meantime, I will comfort myself, that you will take Dumfries in your way; I will be mortally disappointed if you do not."[27]

On 7 July 1796 Robert Burns wrote to Alexander Cunningham "... Mrs Burns threatens in a week or two to add one more to my Paternal charge, which, if of the right gender, I intend shall be introduced to the world by the respectable designation of Alexr Cunningham Burns. My last was James Glencairn, so you can have no objection to the company of Nobility."[28]

On 16 July 1818 Jean wrote to James, enclosing a silver watch as an engagement present, kindly taken to India by Lady Hastings. She expressed her original reservations at his engagement announcement but went on to say "I believe you have maturely considered it and from the account you gave me of the objects of your choice, I can have no objections – I am thankful that she possesses such affections as you describe, you deserve a good wife and I trust you will not be disappointed [sic] in each other – remember in the married state there is much to bear and much to forbear."[13]

Sarah Hutchinson

[edit]Sarah Elizabeth Maitland Tombs Burns became Mrs Hutchinson, marrying Dr Berkely Westrop Hutchinson.[6] Berkely was born in Galway, Ireland and his father was Captain John Francis Hutchinson of the 69th Regiment.[23] Sarah wrote on 27 October 1893 from Cheltenham to Dr. Duncan McNaught, editor of the Robert Burns Federation's 'Burns Chronicle' saying: "I was only 12 years old at my grandmother's death (ie Jean Armour's) consequently I have little recollection of incidents or anecdotes about my grandfather... My father often said it was disgraceful the statements made out by people who lived in the Poet's time, continuing, as they did, so much falsehood and exaggeration of the events of his life. Dr Currie had all the letters and papers sent to him by my grandfather when he wrote the Poet's life, but he never returned them to her, and her sons were too young then to ask for them; so other people became possessed of lettrs and poems of the Poet which ought to have been given back to the family. The copyright of Currie's Life of Burns ought to have been conferred upon his widow, but it was not' — an interesting comment on the methods employed by Dr Currie."[1]

Sarah owned the water-colour of 'The Cotter's Saturday Night' painted by David Allan, saying that Allan had given it to gave to her grandfather. Sarah also had the Burns family Bible and her grandfather's desk.[1]

Mrs Hutchinson's son, Robert Burns Hutchinson, was the only direct male descendant of the poet. He lived in America at Chicago, where he was a clerk in a shipping office and died in Vancouver, British Columbia in 1944.[29]

See also

[edit]- Agnes Burns (aunt)

- Annabella Burns (aunt)

- Isabella Burns (aunt)

- John Burns (uncle)

- Gilbert Burns (uncle)

- William Burns (uncle)

- Francis Wallace Burns (brother)

- William Nicol Burns (brother)

- Elizabeth Riddell Burns (sister)

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l McQueen, p.33

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Westwood (2008). p.21

- ^ Mackay, p.486

- ^ Mackay, p.531

- ^ Westwood (2008), Appendix

- ^ a b c d e f g Purdie, p.62

- ^ West Sussex County Times

- ^ a b Purdie, p.61

- ^ Wargaming Miscellany

- ^ McKay, Page 319

- ^ a b c d e Mackay, p.684

- ^ Westwood (1996), p.146

- ^ a b Westwood (1996), p.148

- ^ Westwood (1996), p.106

- ^ a b c d Sulley (1896), p.61

- ^ a b Westwood (1996), p.159

- ^ Westwood (1996), p160

- ^ The Family of Robert Burns

- ^ Westwood (1996), p.168

- ^ Williams, p.86

- ^ a b Westwood (1996), p.180

- ^ Boyle, p.69

- ^ a b Westwood (1996), p.161

- ^ National Portrait Gallery

- ^ Westwood (1996), p.178

- ^ Boyle, p.41

- ^ Ferguson, p.270

- ^ Ferguson, p.325

- ^ Purdie, p.93

- Sources and further reading

- Boyle, A.M. (1996). The Ayrshire Book of Burns-Lore. Darvel : Alloway Publishing. ISBN 0-907526-71-3.

- Douglas, William Scott (1938). The Kilmarnock Edition of the Poetical Works of Robert Burns. Glasgow : Scottish Daily Express.

- Ferguson, J. De Lancey (1931). The Letters of Robert Burns. Oxford : Clarendon Press.

- Hogg, Patrick Scott (2008). Robert Burns. The Patriot Bard. Edinburgh : Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84596-412-2.

- Hosie, Bronwen (2010). Robert Burns. Bard of Scotland. Glendaruel : Argyll Publishing. ISBN 978-1-906134-96-9.

- Lindsay, Maurice (1954). Robert Burns. The Man, his Work, the Legend. London : Macgibbon.

- Mackay, James (2004). A Biography of Robert Burns. Edinburgh : Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 1-85158-462-5.

- McIntyre, Ian (1995). Dirt & Deity. London : HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-215964-3.

- McQueen, Colin Hunter & Hunter, Douglas (2008). Hunter's Illustrated History of the Family, Friends and Contemporaries of Robert Burns. Published by Messrs Hunter Queen and Hunter. ISBN 978-0-9559732-0-8

- Purdie, David; McCue Kirsteen and Carruthers, Gerrard. (2013). Maurice Lindsay's The Burns Encyclopaedia. London : Robert Hale. ISBN 978-0-7090-9194-3.

- Sulley, Philip (1896). Robert Burns and Dumfries. Dumfries : Thos. Hunter.

- Westwood, Peter J. (1996). Jean Armour, Mrs Robert Burns: An illustrated Biography. Dumfries: Creedon Publications.

- Westwood, Peter J. (1997). Genealogical Charts of the Family of Robert Burns. Kilmarnock : The Burns Federation.

- Westwood, Peter J. (2004). The Definitive Illustrated Companion to Robert Burns. Scottish Museums Council.

- Westwood, Peter J. (Editor). (2008). Who's Who in the World of Robert Burns. Kilmarnock : Robert Burns World Federation. ISBN 978-1-899316-98-4

- Williams, David (2013). Robert Burns and Ayrshire. Catrine : Alloway Publishing. ISBN 978-09-07526-95-7