Indraprastha

Indraprastha (lit. "Plain of Indra"[1] or "City of Indra") is a city cited in ancient Indian literature as a constituent of the Kuru Kingdom. It was designated the capital of the Pandavas, a brotherly quintet in the Hindu epic Mahabharata. Under the Pali form of its name, Indapatta, it is also broached upon in Buddhist texts as the capital of the Kuru Mahajanapada. The topography of the medieval fort Purana Qila on the banks of the river Yamuna matches the literary description of the citadel Indraprastha in the Mahabharata; The city is sometimes also referred to as Khandavaprastha or Khandava Forest, the epithet of a forested region situated on the banks of Yamuna river which, going by the Hindu epic Mahabharata, was cleared by Krishna and Arjuna to build the city.[2]

History

[edit]Indraprastha is referenced in the Mahabharata, an ancient Sanskrit text penned by the author Vyasa. It was one of the five places sought for the sake of peace, and, to avert a disastrous war, Krishna proposed that if Hastinapura consented to give the Pandavas only five villages, namely, Indraprastha, Svarnaprastha (Sonipat), Panduprastha (Panipat), Vyaghraprastha (Baghpat), and Tilaprastha (Tilpat),[3] then they would be satisfied and would make no more demands. Duryodhana vehemently refused, commenting that he would not part with land even as much as the point of a needle. Thus, the stage was set for the great war for which the epic of Mahabharata is known most of all. The Mahabharata records Indraprastha as being home to the Pandavas, whose wars with the Kauravas it describes.

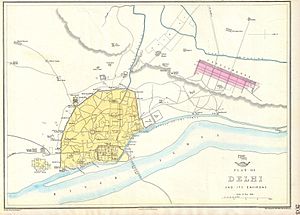

In Pali Buddhist literature, Indraprastha was known as Indapatta. The location of Indraprastha is uncertain, but the Purana Qila in present-day New Delhi is frequently cited[a][5] and has been noted as such in texts as old as the 14th-century CE.[6] The modern form of the name, Inderpat, continued to be applied to the Purana Qila area into the early 20th century;[7] in a study of ancient Indian place-names, Michael Witzel considers this to be one of many places from the Sanskrit Epics whose names have been retained into modern times, such as Kaushambi/Kosam.[8]

Location

[edit]Purana Qila is certainly an ancient settlement but archaeological studies performed there since the 1950s[b][c] have failed to reveal structures and artefacts that would confirm the architectural grandeur and rich lives in the period that the Mahabharata describes. The historian Upinder Singh notes that despite the academic debate, "Ultimately, there is no way of conclusively proving or disproving whether the Pandavas or Kauravas ever lived ...".[6] However, it is possible that the main part of the ancient city has not been reached by excavations so far, but rather falls under the unexcavated area extending directly to the south of Purana Qila.[d] Overall, Delhi has been the center of the area where the ancient city has historically been estimated to be. Until 1913, a village called Indrapat existed within the fort walls.[11] As of 2014, the Archaeological Survey of India is continuing excavation in Purana Qila.[12]

Historical significance

[edit]Indraprastha is not only known from the Mahabharata. It is also mentioned as "Indapatta" or "Indapattana" in Pali-language Buddhist texts, where it is described as the capital of the Kuru Kingdom,[13] situated on the Yamuna River.[14] The Buddhist literature also mentions Hatthinipura (Hastinapura) and several smaller towns and villages of the Kuru kingdom.[13] Indraprastha may have been known to the Greco-Roman world as well: it is thought to be mentioned in Ptolemy's Geography dating from the 2nd century CE as the city "Indabara", possibly derived from the Prakrit form "Indabatta", and which was probably in the vicinity of Delhi.[15] Upinder Singh (2004) describes this equation of Indabara with Indraprastha as "plausible".[16] Indraprastha is also named as a pratigana (district) of the Delhi region in a Sanskrit inscription dated to 1327 CE, discovered in Raisina area of New Delhi.[17]

D. C. Sircar, an epigraphist, believed Indraprastha was a significant city in the Mauryan period, based on analysis of a stone carving found in the Delhi area at Sriniwaspuri which records the reign of the Mauryan emperor Ashoka.[citation needed] Singh has cast doubt on this interpretation because the inscription does not actually refer to Indraprastha and although

"... a place of importance must certainly have been located in the vicinity of the rock edict, exactly which one it was and what it was known as, is uncertain."

-Singh[18]

Similarly, remains, such as an iron pillar, that have been associated with Ashoka are not indubitably so: their composition is atypical and the inscriptions are vague.[6]

See also

[edit]- Swarnprastha

- Ashokan Edicts in Delhi

- Hastinapura

- Mayasabha

- History of Delhi

- Historicity of the Mahabharata

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ For instance, Indologist J. A. B. van Buitenen, who translated the Mahabharata, wrote in 1973 that "there can be no reasonable doubt about the locations of Hastinapura, of Indraprastha (Delhi's Purana Qila [...]), and of Mathura

- ^ Archaeological surveys were carried out in 1954-1955 and between 1969 and 1973.[9]

- ^ The 1954-1955 sessions revealed pottery of the Painted Grey Ware (before c.600 BCE), Northern Black Polished Ware (c.600-200 BCE), Shunga, and Kushan Empire periods. The 1969-1973 sessions failed to reach the PGW levels, but found continuous occupation from the NBPW period to the 19th century: the Maurya-period settlement yielded mud-brick and wattle-and-daub houses, brick drains, wells, figurines of terracotta, a stone carving, a stamp seal impression, and a copper coin.[7]

- ^ Historian William Dalrymple quotes archaeologist B. B. Lal's suggestion, "the main part of the city must probably have been to the south – through the Humayun Gate towards Humayun's Tomb [...] where the Zoo and Sundernagar are now."[10]

Citations

- ^ Upinder Singh (25 September 2017). Political Violence in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. p. 401. ISBN 978-0-674-98128-7.

- ^ C. N. Nageswara Rao (13 November 2015). Telling Tales: For Rising Stars. Partridge Publishing India. pp. 105–. ISBN 978-1-4828-5924-9.

- ^ Kapoor, Subodh (2002). Encyclopaedia of Ancient Indian Geography. Cosmo Publications. p. 516. ISBN 978-81-7755-297-3.

- ^ "1863 Dispatch Atlas Map of Delhi(Indraprastha), India". Geographicus Rare Antique Maps. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ J. A. B. van Buitenen; Johannes Adrianus Bernardus Buitenen; James L. Fitzgerald (1973). The Mahabharata, Volume 1: Book 1: The Book of the Beginning. University of Chicago Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-226-84663-7.

- ^ a b c Singh, Upinder, ed. (2006). Delhi: Ancient History. Berghahn Books. pp. xvii–xxi, 53–56. ISBN 9788187358299.

- ^ a b Amalananda Ghosh (1990). An Encyclopaedia of Indian Archaeology, Volume 2. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. pp. 353–354. ISBN 978-81-215-0089-0.

- ^ Witzel, Michael (1999). "Aryan and non-Aryan Names in Vedic India. Data for the linguistic situation, c. 1900-500 B.C.". In Bronhorst, Johannes; Deshpande, Madhav (eds.). Aryan and Non-Aryan in South Asia (PDF). Harvard University Press. pp. 337–404 (p.25 of PDF). ISBN 978-1-888789-04-1.

- ^ Singh, Upinder, ed. (2006). Delhi: Ancient History. Berghahn Books. p. 187. ISBN 9788187358299.

- ^ William Dalrymple (2003). City of Djinns: A Year in Delhi. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 370. ISBN 978-1-101-12701-8.

- ^ Delhi city guide. Eicher Goodearth Limited, Delhi Tourism. 1998. p. 162. ISBN 81-900601-2-0.

- ^ Tankha, Madhur (11 March 2014). "The discovery of Indraprastha". The Hindu. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ a b H.C. Raychaudhuri (1950). Political History of Ancient India: from the accession of Parikshit to the extinction of the Gupta dynasty. University of Calcutta. pp. 41, 133.

- ^ Moti Chandra (1977). Trade and Trade Routes in Ancient India. Abhinav Publications. p. 77. ISBN 978-81-7017-055-6.

- ^ J. W. McCrindle (1885). Ancient India as Described by Ptolemy. Thacker, Spink, & Company. p. 128.

- ^ Upinder Singh (2004). The discovery of ancient India: early archaeologists and the beginnings of archaeology. Permanent Black. p. 67. ISBN 978-81-7824-088-6.

- ^ Singh (ed., 2006), p.186

- ^ Singh (2006), p.186

External links

[edit] Media related to Indraprastha at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Indraprastha at Wikimedia Commons