Harry Collingwood

Harry Collingwood | |

|---|---|

| Born | 23 May 1843 Weymouth, Dorset |

| Died | 10 June 1922 (aged 79) Chester |

| Nationality | British |

| Other names | William Joseph Cosens Lancaster |

| Occupation(s) | Civil enginineer and novelist |

| Years active | 1860–1922 |

| Known for | Writing boys' adventure stories |

| Notable work | The Pirate Island |

Harry Collingwood was the pseudonym of William Joseph Cosens Lancaster (23 May 1843 – 10 June 1922),[1] a British civil engineer and novelist who wrote over 40 boys' adventure books, almost all of them in a nautical setting.

Early life

[edit]Collingwood was the eldest son of master mariner Captain William Lancaster (1813 – (1861 – 1871))[2] and Anne, née Cosens (c. 1820 – 9 October 1898).[3] His birth certificate shows that he was born in Weymouth, Dorset on 23 May 1843 at 9:30am at Concord Place. The Oxford Dictionary Of National Biography notes that most references, except his birth certificate, give his date of birth as 1851.[4] His application for Associate Membership of the Institution of Civil Engineers gives his birth date as 23 May 1846.[5]

Collingwood was the first of three children for the couple. He was eight when his sister Ada Louise (c. 1852 – 8 January 1929)[6] was born and 12 when his sister Sarah Anne (1 June 1853 – 27 December 1941) was born.[7] Both women were shown as drapers assistants in the 1871 census. By then Collingwood's father had died, and his mother continued to live with her daughters until her death. Ada never married and lived with her sister after leaving the paternal home. Sarah Anne married Mathew Smellie in St Michaels, Toxteth, Liverpool, Lancashire on 30 June 1880.[8] The couple had one child, Harold Ernest Smellie (11 April 1881 – 30 April 1961).[9][10] Harold was the nephew who registered Collingwood's death in 1922.[4][note 1] Collingwood's mother died at his home in Norwood on 9 October 1898, with her daughter Ada Louise as the executrix of her effects of £1,308 11s 11d.[3] When Ada Louise died on 8 January 1929, her widowed sister Sarah Ann (with whom she was living) was the executrix for her effects of £1,907 16s 8d.[6] Harold was the executor for the effects (£4,574, 15s 1d) of his mother Sarah Ann when she died on 27 December 1942.[7]

Most sources[4][12][13][14] state that he attended the Royal Naval College, Greenwich and distinguished himself there by carrying off many prizes.[13] However, this college closed in 1837,[15] and when it reopened it was only for those who had passed the exam for lieutenant. Kirk states that Collingwood attended the Royal Naval School, which was at New Cross, near Greenwich.[16][17] This school had over 210 boys destined for careers at sea on the rolls by 1865[18] and trained officers and men for both the Royal Navy and Merchant Marine.[19] In Collingwood's first book The Secret of the Sands the hero, called Harry Collingwood, was educated at the Royal Naval School at Greenwich.[20]

Collingwood joined the Royal Navy as a midshipman at 15.[4] However, his severe near-sightedness forced him to abandon his chosen career. Kitzen states that Collingwood traveled widely in both his short naval and much longer civilian career.[21] Kirk states that it was during his civilian career that Collingwood traveled widely.[16]

Work as an engineer

[edit]In September 1860, at age 17, he began working as a pupil in the architectural office of G R Crickmay RIBA in Dorset.[5] That architectural practice continues today under the name of John Stark and Crickmay.[22] He continued in Dorset until March 1864 and then moved to Durban in South Africa. He worked there in a range of posts until the end of 1870, by which time he was the Government Engineer and Surveyor for the Port District of Natal.

He returned to the UK in 1871 and worked on an eight-mile section of the Devon to London Railway for two years (the section of the London and South Western Railway from Okehampton to Lydford was under construction at this time). He continued in the UK, working on a range of projects including harbour works in the Isle of Man, as well as work at Burntisland on the Firth of Forth, where he lived in 1880, while advertising in Coleraine in Northern Ireland, for accommodation for himself, his wife, and infant son.[23] In 1888 he spent a year on the island of Trinidad, surveying for a deep-water port and associated railway.[5] He also travelled to the Baltic, Mediterranean, and the East Indies.[4] His wide travels provided accurate backgrounds for many of his works.

Returned to England, and now living in Norwood, London, Collingwood applied for associate membership of the Institution of Civil Engineers on 31 July 1889 and was elected on 3 December 1889. Associated membership is the grade of membership open to engineers who are not academically qualified Civil Engineers,[24] but have learned to engineer by another route.

In 1893 Collingwood was one of the three short-listed candidates from the 89 applicants for Resident Engineer at Llanelli Harbour, Carmarthenshire[25] but was unsuccessful.[26] From 1894 to 1896 he was the engineer, working out of London, for works on the River Bann for the Coleraine Harbour Commissioners.[27] In 1906, Collingwood moved to Mutley in Plymouth. By 1908 he was back in London, at New Bushey in Watford, London.

Marriage and son

[edit]On 10 July 1878, at Conisborough near Doncaster,[28] Collingwood married Kezia Hannah Rice Oxley (1848 – 18 April 1928),[29] the fourth child of George Oxley, a provisions dealer, and Mary Rice.[30] Like Collingwood's two sister, Kezia worked as a draper's assistant in Liverpool. The Oxley's were a large family and Kezia had two sisters and seven brothers. One of her brothers, Sir Alfred James Rice-Oxley (25 January 1856 – 10 August 1941) was a physician to members of the Royal Family.[31]

Her nephew Alan Rice-Oxley was a flying ace in World War I,[32] and Alan's sister married Kezia's only son (her first-cousin) in 1906. Kezia's family were close and both the 1891 and 1901 census show relatives staying with her. The couple had a son William Arthur Percy Lancaster, generally known as Percival Lancaster, (1880-1937) born at Park House in Burntisland, Scotland, on 24 February 1880 at 8:30am.[28] He followed his father's example, not only becoming a Civil Engineer but also a novelist.[33]

Death

[edit]Collingwood died suddenly at his sister Sarah's house at 40 Liverpool Road, Chester on 10 June 1922,[34] only five days after the death of Sarah's husband. Collingwood left the relatively modest sum of £866 11s. 8d. to his widow.[35] Kezia died in London on 18 April 1928, leaving £1,028 18s. 7d. to her son William Arthur Percy, then described as a Surveyor rather than a Civil Engineer.[29]

Alleged inspiration for Swallows and Amazon

[edit]Sutherland states of Collingwood that "His most enduring monument is that his yacht Swallow inspired his friend Arthur Ransome's children's book Swallows and Amazons."[14] However, Ransome did not write the book until 1929 - seven years after Collingwood's death. The Swallow that served as Ransome's inspiration was the sailboat belonging to W. G. Collingwood, who was no relation.

Ransome learned to sail, at age 12, in W. G. Collingwood's boat Swallow at Coniston in 1896.[36] He then repaid the favour by teaching W. G. Collingwood's grandchildren, the five Altouyans, to sail in "Swallow II" in 1928.[37]

Writing

[edit]

Collingwood's first novel in 1878, the year of his marriage, was The Secret of the Sands, a tale of the sea with piracy and buried treasure thrown in. The hero and pseudonymous author of this tale was “Harry Collingwood”. This pseudonym was chosen by the author in homage to Vice-Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood (whom Thackeray described as a virtuous Christian knight). This was clearly intended as an adult book. At the time, adult books were typically produced in three volumes, whereas books for the juvenile market were typically produced in a single volume with illustrations.[38]

In the preface to his first novel, Collingwood stated that ". . . my purpose has simply been to combine a little information with, I hope, a great deal of interest and amusement; and if my book serves but to while pleasantly away an idle hour or two for the general reader, or conveys a scrap of useful information to the young yachtsman, that purpose will be fully accomplished." Collingwood was well considered as a story teller, and especially as a teller of sea stories. Reviewers at the time wrote:

- "As a story-teller Mr Collingwood is not surpassed. — Spectator[39]

- "Mr. Harry Collingwood, we need hardly say, does know how to tell a story..." — Academy[40]

- "...well known as the writer of tales of adventure by sea..." — Athenaeum[41]

- "Mr. Collingwood writes of the sea with a sympathy and understanding which are all too rare in writers of boys’ books, and his hero is a fine character, well drawn." — The Academy[42]

- "His descriptions of adventure at sea are not surpassed by those of any other writer for boys, while his plots are of an exciting nature" — Morning Post[43]

- "In sea stories this talented author excels, and this is one of his best. It is full of wonderful adventure told in a style which holds the reader spell-bound" — Practical Teacher[44]

- "... in our opinion the author is superior in some respects as a marine novelist to the better-known Mr. Clark Russell" — The Times[45]

- "Another excellent yarn-spinner, and one who rivals Mr. Clark Russell in his ability to get the “whiff of the briny” into his pages, is Mr. Harry Collingwood" — St. James's Gazette[46]

Collingwood was popular, and his novels remained in print for a long time. In 1913, Blackie was still offering 18 novels by Collingwood they had published over the previous two decades, and only one, An Ocean Chase was not included.[47] Ellis noted that in the 1920's, adventures stories were represented by the work of Harry Collingwood, Captain W.E. Johns, and Percy Westerman.[48] Sternlicht list him as one of the four standard boys' novelists of C. S. Forester's childhood.[49][note 2] Collingwood was one of the authors of children's fiction that D. H. Lawrence recommended for translation into Russian.[50] Sampson Low were still advertising all 6 titles by Harry Collingwood that they had published in an advertisement published in the late 1930s.[51] Dizer notes that Collingwood's books were being re-issued in England through at least 1939.[52]: 131

Dizer notes that apart from the three science fictions stories about the Flying Fish Collingwood's books are mainly sea stories of young English heroes.[52]: 142 Unlike G. A. Henty, whose heroes are often public schoolboys,[53] Collingwoods heroes are usually from the Merchant Navy or Royal Navy, and public schools are rarely referred to. Unlike G. A. Henty who has occasional Scottish and Irish heroes, Collingwood's heroes, with very few exceptions, are English.[note 3]

Collingwood's professional background occasionally appears in the novels. The hero in Harry Escombe; a tale of adventure in Peru (1910) was an engineering surveyor. The eponymous hero of Geoffrey Harrington's Adventures was a manager of an engineering company, and the hero of The Cruise of the Thetis was the head of a marine engineering and shipbuilding enterprise. Engineers also appear as strong secondary characters in such stories as The Pirate Island (1884) and The Missing Merchantman (1888).

Ferreira examines some of the underlying prejudices displayed by Collingwood in Harry Escombe; a tale of adventure in Peru.[54] In With Airship and Submarine (1908) he describes anarchists as "enemies of society and of the human race".[55]

Almost all of Lancaster's novels have a predominantly nautical theme. Even those that don't often include a long sea-voyage. Three, featuring a flying submarine, are frank science fiction. Several of the works, most especially Geoffrey Harrington's Adventure (1907), include a lost white tribe in the story. Other recurrent themes in Lancaster's novels include storms, shipwreck, being castaway, piracy, slavery, buried treasure, long voyages in open boats, disasters at sea, derelict ships, and pearl fishing. Lancaster excelled at swimming, rifle-shooting, and horse-riding and these skills can sometime be found among the heroes of his novels. Lancaster was a keen yachtsman and yacht designer and the design of small craft to escape from isolated islands is a recurring theme in the novels.

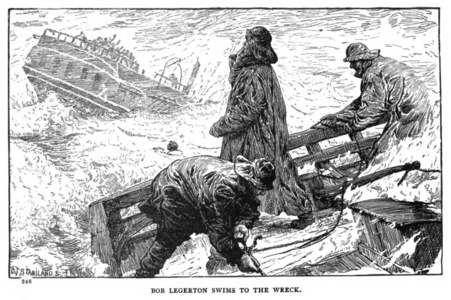

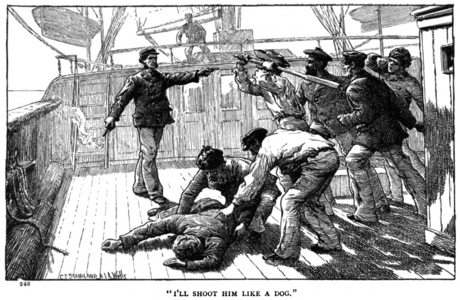

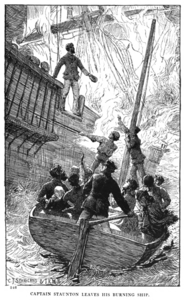

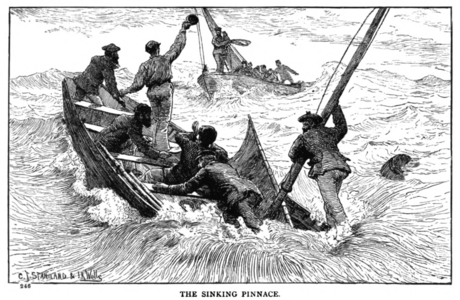

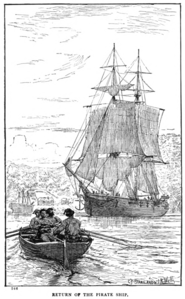

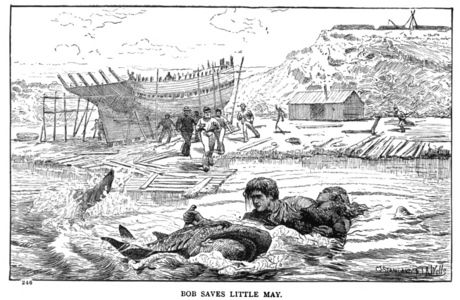

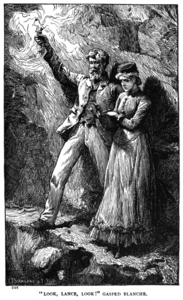

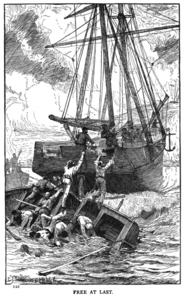

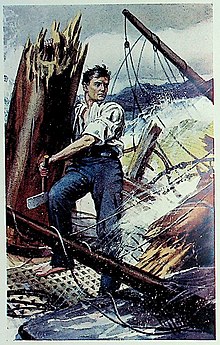

Sample illustrations from a Collingwood book

[edit]The following illustrations by C. J. Staniland[note 4] and J. R. Wells[note 5] were for The Pirate Island, a story of the South Pacific (1884, Blackie, London) by Collingwood. The illustrations cover common themes in Collingwood's works: personal bravery, swimming, mutiny, fires at sea, piracy, treasure, voyages in open boats, and fighting sharks.

-

Page 20

-

Page 97

-

Page 113

-

Page 126

-

Page 175

-

Page 222

-

Page 247

-

Page 328

Background to the books

[edit]Nield, speaking of historical fiction, says that among the most deservedly popular of recent imaginative writers ... Of those who cater for young people, ... Harry Collingwood ... may be mentioned as having come well to the fore.[61] However, The Athenaeum noted that of The Log of a Privateersman, that The book, as such a book has a right to do, sets history, chronology, and law at defiance ; but the story is told with life and vigour which carry it swimmingly over the most absolute impossibilities.[41]

The novels set in a particular historical context include:

- The three novels set in the late 16th Century are set in the context of the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) with one The Cruise of the 'Nonsuch' Buccaneer set in the context of the aftermath of the Battle of San Juan (1595).

- The four books and one short story set in the West Africa Squadron deal with the blockade of Africa for the suppression of the Atlantic Slave Trade. However, Kitzan stated that: The slaves are but a vehicle to provide a rationale for a series of rousing and deadly adventures.[62]

- Under the Chilian Flag (1909) is set in the context of the War of the Pacific of 1879-1884 between Chile and a Bolivian-Peruvian alliance.

- Under the Ensign of the Rising Sun was set in the context of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1908.

- A Chinese Command (1915) is set against the context of the Donghak Peasant Revolution for whom the hero is smuggling arms, and the resulting First Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895, and the story effectively ends with the signing of the Treaty of Shimonoseki.

- Under the Meteor Flag (1884) is set in the French Revolutionary Wars.

- Blue and Grey is set in the American Civil War and specifically around the events of the Battle of Cherbourg (1864).

- The Cruise of the 'Thetis' (1910) is set during the Cuban War of Independence 1895–1998.

However, the novels should not be taken as accurate portrayals of historical fact, as Lancaster changes event to suit the plot. In The Cruise of the 'Nonsuch' Buccaneer for example, Drake's attack on San Juan is presented as Spanish treachery in violation of a truce rather than the blatant attempt to sack the city. In Warship International, Sturton, commenting about the description of the Battle of Yalu in A Chinese Command, said: The book's account of the battle is not factual; only three Chinese and three Japanese ships are named correctly and certain lurid episodes are entirely fictional.[63]

Books with son

[edit]As well as his solo writing Lancaster wrote one published work In the Power of the Enemy (1925) together with his son. This was originally published as a serial in an English magazine in 1912.[64] Collingwood and his son wrote another unpublished manuscript: The Fourth Temptation. The Love Story of Mary Magdalene.[65] This may have been the manuscript that Percival referred to as being taken to England by the Managing Director of Sampson Low in 1912. Collingwood was in Toronto with his son at the time.[64]

Percival wrote two book himself, Captain Jack O'Hara R.N. (1908) and Chaloner of the Bengal Cavalry: a Tale of the Indian Mutiny (1915). The Serpent, was set in New Zealand and was due for publication in 1913.[33] The Ship of Silence is referenced on the title page of In the Power of the Enemy[66] – Percival wrote a short story under this name for MacLeans.[67]

List of works

[edit]Please see Works by Harry Collingwood for a list of works by the author.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Collingwood died at the house of Harold's parents, so it is not surprising that Harold rather than Collingwood's son Percival registered the death. Additionally, Harold must have been familiar with the procedure as his father had died only five days before.[11]

- ^ The other three were G. A. Henty, R. M. Ballantyne, and Robert Leighton.[49]

- ^ The hero of Blue and Grey about the American Civil War is American, and the hero of The Rover's Secret had an Italian mother.

- ^ Charles Joseph Staniland RI ROI (19 June 1838 – 16 June 1916) was a marine painter and illustrator, and a frequent contributor to first the Illustrated London News and then The Graphic.[56]: 44 Van Gogh was an admirer of Staniland's Work.[57] Staniland was a prolific illustrator of juvenile fiction,[58]: 462-267 in some cases working with J. R. Wells.

- ^ Josiah Robert Wells (1849–1897) was an artist and illustrator specialising in maritime topics. He was the Special Artist for marine subject for the Illustrated London News.[59] He boarded in London with C. J. Staniland, for whose family his sister Rosa acted as governess.[60]

References

[edit]- ^ "Wrote Boys' Stories; W. J. C. Lancaster (Harry Collingwood) Dead", The Gazette (Montreal), 4 July 1922 p. 4

- ^ "England, Sussex, Parish Registers, 1538-1910". FamilySearch. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Wills and Probates 1858-1996: Pages for Lancaster and the year of death 1898. p.62". Find a Will Service. p. 62. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Arnold, Guy (23 September 2004). "Lancaster, William Joseph Cosens [pseud. Harry Collingwood] (1843–1922), children's writer / Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/58983. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b c Lancaster, William Joseph Cosens (31 July 1889). Summary of experience in application for Associate Membership of the Institution of Civil Engineers. Ancestry.com. UK, Civil Engineer Records, 1820-1930 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, US: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2013.: Institution of Civil Engineers.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ a b "Wills and Probates 1858-1996: Pages for Lancaster and the year of death 1929. p.14". Find a Will Service. p. 14. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Wills and Probates 1858-1996: Pages for Smellie and the year of death 1942, p. 216". Find a Will Service. p. 216. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ Liverpool Record Office (30 June 1880). "Liverpool Record Office; Liverpool, England; Reference Number: 283 HAM/3/15". Liverpool, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1932. Liverpool: Liverpool Records Office. p. 27.

- ^ Liverpool Record Office (30 June 1880). "Liverpool Record Office; Liverpool, England; Reference Number: 283 AND/2/2". Liverpool, England, Church of England Baptisms, 1813-1917. Liverpool: Liverpool Records Office. p. 39.

- ^ "Wills and Probates 1858-1996: Pages for Smellie and the year of death 1961". Find a Will Service. p. 420. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ "Wills and Probates 1858-1996: Pages for Smellie and the year of death 1922". Find a Will Service. p. 301. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ^ Hayes, David. "Harry Collingwood". Historic Naval Fiction. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ a b Doyle, Brian (1968). The Who's Who of Children's Literature. London: Hugh Evelyn Limited. p. 55. ISBN 0238788121.

- ^ a b John Sutherland (13 October 2014). The Longman Companion to Victorian Fiction. Routledge. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-317-86333-5. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ Pack, S. W. C. (1966). Brittania at Dartmouth (The Beginning ed.). London: Alvin Redman Limited. p. 27.

- ^ a b Kirk, John Foster; Allibone, Samuel Austin (1899). A supplement to Allibone's Critical dictionary of English literature and British and American authors: Containing over thirty-seven thousand articles (authors), and enumerating over ninety three thousand titles. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company. p. 969. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ The Naval and military sketch book, and history of adventure by flood and field. 1845. pp. 147–149.

- ^ G. F. Cruchley (1865). Cruchley's London in 1865: A Handbook for Strangers, Etc. p. 217. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ Various authors (1876). "Royal Naval School, Greenwich". The Nautical Magazine for 1876. Cambridge University Press. pp. 128–130. ISBN 9781108056557.

- ^ Collingwood, Harry (1879). The Secret of The Sands. Vol. 1. London: Griffith and Farran. p. 36.

- ^ Kitzan, Laurence (2001). Victorian Writers and the Image of Empire: The Rose-colored Vision. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-313-31778-1. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ John Stark and Crickmay (2012). "John Stark and Crickmay:History". Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ Lancaster, W. J. C. (4 September 1880). "Apartments, Comfortably, Wanted in Coleraine". Coleraine Chronicle (Saturday 04 September 1880): 5.

- ^ Institution of Civil Engineers. "Grades of ICE membership". ICE Institution of Civil Engineers. Archived from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ^ "Llanelly Harbour Commission: The Post of Resident Engineer". Western Mail (Saturday 12 August 1893): 7. 15 August 1893.

- ^ "Llanelly's New Harbour Master". South Wales Daily News (Thursday 24 August 1893): 4. 24 August 1893.

- ^ The Harbour Commissioners of the Port of Coleraine (18 June 1994). "Bann Navigation (call for Tenders for the construction of a Training Bank)". Northern Whig (Monday 18 June 1894).

- ^ a b National Records of Scotland. "1880 Lancaster William Arthur (Statutory registers Births 411/ 34)". ScotlandsPeople. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ^ a b "Probate records for the name Lancaster in 1928". Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ "Kexia Hannah Alice Oxley 1848-". Main Blackett Tree. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ "Obituary: Sir Alfred Rice-Oxley, C.B.E. M.D.". British Medical Journal. 1941 (2): 286–7. 23 August 1941.

- ^ "Determined to be in the Fight". Sheffield Daily Telegraph (Tuesday 05 November 1918): 2. 5 November 1918.

- ^ a b The Bookman. Vol. XLII (No 253 ed.). Hodder and Stoughton. 1913. pp. 4–5. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ "News in Brief: Interesting News from all Quarters". Shields Daily News (Friday 16 June 1922): 4. 16 June 1922.

- ^ "Probate records for the name Lancaster in 1922". Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ Dearden, James (23 September 2010). "Collingwood, William Gershiom (1854-1932) / Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/39918. Retrieved 27 January 2020. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Avery, Gillian (23 September 2004). "Ransome, Arthur Michell (1884–1967) / Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35673. Retrieved 27 January 2020. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Newbolt, Peter (1996). "Appendix IV: Illustration and Design: Notes on Artists and Designers: Overend, William Heysham, ROI, 1851-1898". G.A. Henty, 1832-1902 : a bibliographical study of his British editions, with short accounts of his publishers, illustrators and designers, and notes on production methods used for his books. Brookfield, Vt.: Scholar Press. p. 612. ISBN 9781859282083. Retrieved 26 April 2020 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ Blackie (1990). Advertisement in the catalogue Blackie and Son's Books for Young People annexed to Won by the Sword: A tale of the Thirty Years War by G.A. Henty. p. 13. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ "The Academy: July-December 1892, Vol 42: Gift Books, Dec 17, 1892, page 563". Internet Archive. 17 December 1892. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ a b "Christmas Books". The Athenaeum. 3607: 836. 12 December 1896. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ "The Academy: July-December 1906, Vol 71: Christmas Books for Boys, December 1, 1909, page 548". Internet Archive. 1 December 1906. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ "Advertisement by Messers Methuen on page 520 of The Academy: July-December 1892, Vol 42, Dec 10, 1892". Internet Archive. 10 December 1892. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ Blackie (1890). Advertisement in the catalogue Blackie and Son's Books for Young People annexed to Won by the Sword: A tale of the Thirty Years War by G.A. Henty. p. 23. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ Charles Scribner's Sons (1894). Popular Book for Young People in the Catalogue for Charles Scribner's Sons annexed to With Wolf in Canada, or, or The Winning of a Continent by G.A. Henty. p. 11. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ "Tales of the Sea". St James's Gazette (Saturday 30 October 1897): 12. 30 October 1897.

- ^ Collingwood, Harry (1913). Through Veld and Forest. London: Blackie. p. opp. Title page. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ Alec Ellis (16 May 2014). A History of Children's Reading and Literature: The Commonwealth and International Library: Library and Technical Information Division. Elsevier Science. p. 161. ISBN 978-1-4831-3814-5.

- ^ a b Sternlicht, Sanford (1999). C. S. Forester and the Hornblower Saga (Rev. ed.). Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. p. 18. ISBN 9780815606215. Retrieved 16 October 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Burwell, Rose Marie (1970). "A Catalogue of D. H. Lawrence's Reading from Early Childhood". The D.H. Lawrence Review. 3 (3): iii–330. JSTOR 44233338. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ Sampson Low (1937). Page 2 of Sampson Low's Junior Books for Boys and Girls, annexed to Sailing Alone Around the World by Joshua Slocum. London: Sampson Low, Marston and Co., Ltd. p. 7. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ a b Dizer, John (1997). Tom Swift, the Bobbsey Twins, and Other Heroes of American Juvenile Literature: Studied in American Literature Vol. 25. New York: The Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0-7734-8641-0.

- ^ Jeffrey Richards (1989). Imperialism and Juvenile Literature. Manchester University Press. pp. 78–. ISBN 978-0-7190-2420-7.

- ^ Ferreira, Nair María Anaya (2001). La Otredad del mestizaje: América Latina en la literatura inglesa. UNAM. pp. 86–88. ISBN 978-968-36-8526-1.

- ^ Harry Collingwood (1908). "One". With Airship and Submarine: A Tale of Adventure. Library of Alexandria. ISBN 978-1-4655-3758-4.

- ^ Thorpe, James (1935). English Illustration: The Nineties. London: Faber and Faber.

- ^ Newbolt, Peter (1996). "Appendix IV: Illustration and Design: Notes on Artists and Designers: Staniland, Charles Josepth, RI, ROI, 1838-1916". G.A. Henty, 1832-1902 : a bibliographical study of his British editions, with short accounts of his publishers, illustrators and designers, and notes on production methods used for his books. Brookfield, Vt.: Scholar Press. p. 639. ISBN 9781859282083. Retrieved 19 May 2020 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, Robert J. The Men Who Drew For Boys (And Girls): 101 Forgotten Illustrators of Children's Books: 1844-1970. London: Robert J. Kirkpatrick.

- ^ "Our Artists: Past and Present". Illustrated London News (Saturday 14 May 1892): 16. 14 May 1892. Retrieved 3 August 2020 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Well, Josiah Robert". Suffolk Artists. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ Nield, Jonathan (1911). A guide to the Best Historical Novels and Tales (4th ed.). London: Elkin Mathews. p. xii. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ Laurence Kitzan (2001). Victorian Writers and the Image of Empire: The Rose-colored Vision. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-313-31778-1.

- ^ Sturton, I.A. (1993). "Comments and Corrections, Ask Infouser". Warship International. 30 (4). International Naval Research Organization: 423–426. ISSN 0043-0374. JSTOR 44889561.

- ^ a b "A Sketch of Percival Lancaster". Bookseller & Stationer and Office Equipment Journal. 28 (7). Montreal: 27. 1 July 1912. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- ^ "The Fourth Temptation. The Love Story of Mary Magdalene: Original Manuscript". AbeBooks.com. Hyraxia Books. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ Lancaster, Percival; Collingwood, Harry. In The Power of the Enemy. Sampson Low, Marston & Co., Ltd. p. Title page.

- ^ Lancaster, Percival (1 October 1909). "The Ship of Silence: A Tale of the New Canadian Navy". Busy Man's Magazine. MacLeans. pp. 52–56. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

External links

[edit]- Works by Harry Collingwood at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Harry Collingwood at the Internet Archive

- The Online Books Page for Harry Collingwood

- British Library Catalogue listing for Harry Collingwood (i.e. William Joseph Cosens Lancaster)

- Historic Naval Fiction page for Harry Collingwood

- Works by Harry Collingwood at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by G.A. Henty at Project Gutenberg

- 1843 births

- 1922 deaths

- British civil engineers

- People from Weymouth, Dorset

- English historical novelists

- 19th-century English novelists

- Maritime writers

- Writers about the Age of Sail

- Nautical historical novelists

- Victorian novelists

- Writers of historical fiction set in the Middle Ages

- Writers of historical fiction set in the early modern period

- Writers of historical fiction set in the modern age