Harrington v. Purdue Pharma L.P.

| Harrington v. Purdue Pharma L.P. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued December 4, 2023 Decided June 27, 2024 | |

| Full case name | William K. Harrington, United States Trustee, Region 2 v. Purdue Pharma L.P., et al. |

| Docket no. | 23-124 |

| Citations | 603 U.S. ___ (more) |

| Argument | Oral argument |

| Decision | Opinion |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Bankruptcy Court's Confirmation Order and related Advance Order vacated, In re Purdue Pharma, 635 B.R. 26 (S.D.N.Y., 2021), order affirmed in part, reversed in part, In re Purdue Pharma LP, 69 F. 4th 45 (2nd Cir., May 30, 2023); cert. granted (Aug. 10, 2023) |

| Questions presented | |

| Whether the Bankruptcy Code authorizes a court to approve, as part of a plan of reorganization under Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code, a release that extinguishes claims held by nondebtors against nondebtor third parties, without the claimants’ consent. | |

| Holding | |

| The bankruptcy code does not authorize a release and injunction that, as part of a plan of reorganization under Chapter 11, effectively seek to discharge claims against a nondebtor without the consent of affected claimants. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Gorsuch, joined by Thomas, Alito, Barrett, Jackson |

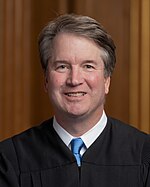

| Dissent | Kavanaugh, joined by Roberts, Sotomayor, Kagan |

| Laws applied | |

| Title 11 of the United States Code | |

Harrington v. Purdue Pharma L.P., 603 U.S. ___ (2024), is a United States Supreme Court case regarding Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code.[1] This case is about the settlement by Purdue Pharma for opioid victims who overdosed with the OxyContin drug produced by the company. The justices determined that the Bankruptcy Code does not authorize the claimant's order, blocking the bankruptcy plan.

Background

[edit]In 1995, Purdue Pharma developed and produced OxyContin, a semi-synthetic opioid. It was subsequently approved by the Food and Drug Administration. From 1996 to 2001, Purdue Pharma extensively marketed OxyContin to both doctors and patients, claiming the drug had little to no risk of addiction. During this period of outreach and marketing, six members of the Sackler family sat on the company's board, including Richard Sackler, who was closely associated with the implementation of the company's deceptive marketing strategy.[2] As a result, prescription and use of the drug increased drastically, coinciding with increased rates of abuse across the nation. This subsequently resulted in what is now known as the opioid epidemic in the United States.[3]

From 2000, the side effects of opioids were starting to be more prevalent, resulting in an influx of lawsuits in the years afterward.

Anticipating that they might be liable in these lawsuits, both civilly and criminally, the Sackler family decided to reallocate revenue from Purdue Pharma to their own trusts and holding companies. This reduced the financial standing of Purdue Pharma to fend off the lawsuits. Eventually, by 2019, all Sackler family members that were on the board of directors of Purdue Pharma had resigned.

In 2019, the Department of Justice (DoJ) brought criminal and civil charges against Purdue Pharma, alleging that its actions defrauded the United States and violated federal kick-back statutes.[3]

In the same year, Purdue Pharma filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, whereas the Sackler family did not.[3] As part of its bankruptcy proceedings, Purdue Pharma sought an injunctive stay on all the lawsuits, towards the company and the Sacklers.

Lower Courts

[edit]The United States Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York sided with Purdue Pharma and granted the stay. In accordance to the Bankruptcy Code, a mediation was opened to avoid the liquidation of the company. Eventually, a plan was agreed by the company, the Sacklers and 15 other non-consenting states. The $8.3 Billion settlement deal would oversee the restructuring of Purdue Pharma and the redistribution of financial relief to the families of opioid victims in payments ranging from $26,000 and $40,000.[4][5] In addition, the settlement would result in the enjoinment of any third-party lawsuits against the Sacklers and the protection of the Sacklers from disclosing certain internal information from creditors and state officials.[6]

| Bankruptcy in the United States |

|---|

|

| Bankruptcy in the United States |

| Chapters |

| Aspects of bankruptcy law |

This agreement was eventually agreed to by judge Robert Drain[7] as it was deemed to have satisfied 3 of the court's criteria.[8] Soon after, the bankruptcy plan was challenged by additional states, appealing to the District Court for the Southern District of New York, which reversed and vacated the Bankruptcy Court's ruling, deeming the Bankruptcy Code did not permit these "third-parties" releases.[9][10]

The District Court ruling was subsequently appealed to the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.[11] The Court of Appeals reversed the District Court's ruling, reaffirming the Bankruptcy Court ruling; and held that the approval of the releases was permissible as the Bankruptcy Court had "Statutory Authority" consistent with Second Circuit case law.[12] Representing the United States Bankruptcy Trustees, the Justice Department appealed the Circuit Court decision to the Supreme Court, urging for a stay on the lower court's decision and for a review of the entire bankruptcy proceeding, describing the settlement as an "unprecedented agreement" that would protect the Sackler's family from opioid-related civil claims.[13][14] On August 10, 2023, the Supreme Court granted a stay in the lower court's decision and granted certiorari; with oral arguments occurring on December 4, 2023.[15][16]

Supreme Court

[edit]Oral arguments

[edit]Oral arguments were heard December 3, 2023.[17] Representing the Federal Government, Former Deputy Solicitor General Curtis E. Gannon argued that Section 1123(b)(6) did not permit for the release of the Sacklers, as nonconsensual third-party releases are not authorized by the Bankruptcy Code given they extinguish property rights that do not belong to the bankruptcy estate.[18] Pratik A. Shah argued on behalf of The Official Committee of Unsecured Creditors of Purdue Pharma L.P. while Gregory Gare argued on behalf of Purdue Pharma.[19] In his argument, Gare contended that the notion that all non-consensual third-party releases are invalid was contradicted by Section 1123(b)(6), as it provides for "any other appropriate provision not inconsistent with" other bankruptcy laws to be used.[20][18] Shah provided similar arguments in favor of a broader reading of Section 1123(b)(6) and emphasized the direct effects such an interpretation would have on the victims.[21] In doing so, Shah noted that if such a determination was not adopted by the court, a vast majority of opioid victims would not receive financial compensation, as, given the $40 trillion worth of lawsuits that stood against Purdue and the Sacklers, the first successful lawsuit would likely result in such a large payout that it would eliminate any recovery for additional victims in future lawsuits.[22] Justice Kavanaugh appeared sympathetic towards the arguments presented by Gare, stating that such language appeared to be sufficiently broad and well-supported, as there had been 30 years’ worth of practice in the bankruptcy courts approving the release and indemnification from liability by a company of its officers or directors who are parties in such cases.[20][23] Justices Gorsuch and Jackson conversely questioned Gare's position on the broadness of the provision arguing that the terminology of 'appropriate' garnered some limitations in terms of what was applicable.[18]

Majority

[edit]

Writing for the majority, Justice Neil Gorsuch, joined by Justices Thomas, Alito, Barrett, and Jackson overturned the bankruptcy settlement.[24][25] In his opinion, Gorsuch contended that federal bankruptcy laws did not allow for the non-consensual third-party release and injunction of the Sackler family from criminal liability without the consent of the creditors and opioid victims.[26][27] According to Gorsuch, provision §1123(b)(6), which indicates a bankruptcy plan may "include any other appropriate provision not inconsistent with" other bankruptcy laws, does not give the bankruptcy courts broad powers in Chapter 11 bankruptcy reorganization.[28][29] As such, this "catchall" provision did not permit for any and all bankruptcy provisions to be inserted into a reorganization plan, but rather, only those applying to scenarios in the preceding subsections of §1123(b).[28] Given all similar preceding scenarios involved either debtors or responsibilities to creditors, only provisions relating to either were permissible.[29][30] Given this, whether or not the Sackler family were permitted to move forward with the non-consensual third-party release required an affirmative determination that they were considered to be 'debtors'.[31]

The obtainment of a release of a debtor's debt liability requires "virtually all [of its] assets" to be put on the table"; an action which Gorsuch determined to not have been taken by the Sackler family as they maintained billions of dollars in profit accrued from Purdue Pharma and avoided personal Bankruptcy.[29][30] Additionally, such a discharge also typically operated only for a debtor's benefit against its creditors and didn't extend to additional creditor claims of fraud or willful or malicious injury.[31] Given such actions were, respectively, not taken by or accurate of the Sackler family, the family were not determined to be 'debtors' but rather 'nondebtors', and were therefore not subject to the benefit of the non-consensual non-debtor claim extinguishment permitted by Chapter 11.[32][31] As such, Gorsuch determined that the subsequent "catchall" provision "cannot be fairly read to endow a bankruptcy court with the 'radically different' power to discharge the debts of a nondebtor without the consent of affected nondebtor claimants".[28][29] Gorsuch again contended that the non-consensual release of nondebtor liability by bankruptcy laws was only utilized in asbestos-related bankruptcies, and whose limited authorized use "makes it all the more unlikely" that such a "catchall" provision would be interpreted to approve such releases in all scenarios.[29][33] Such a release could therefore not move forward as, even the 'broad equitable powers' of the bankruptcy courts that would allow for such a release, could only move forward when such actions were deemed "necessary or appropriate to carry out the provisions of" the bankruptcy code, which was determined not to be the case.[30]

Dissent

[edit]

Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote the dissenting opinion joined by Chief Justice Roberts alongside Justices Sotomayor and Kagan.[34][35] In his opinion, Kavanaugh wrote that federal bankruptcy law provides bankruptcy courts with the "broad discretion to approve 'appropriate' plan provisions" to ensure that a bankrupt company’s assets are distributed fairly among its creditors rather than going to whoever can file a lawsuit first.[29] Given a company such as Purdue typically pays for claims against company officials, Kavanaugh reasoned that those officials may be shielded from liability as part of the bankruptcy plan, particularly when the officials are willing to contribute money to settle the bankruptcy.[29] In addition, Kavanaugh emphasized the real-world effects of the abrogation of such a settlement, writing: "The opioid victims and their families are deprived of their hard-won relief. And the communities devastated by the opioid crisis are deprived of the funding needed to help prevent and treat opioid addiction [...] As a result of the Court's decision, each victim and creditor receives the essential equivalent of a lottery ticket for a possible future recovery for (at most) a few of them".[36][37]

References

[edit]- ^ "Justices put Purdue Pharma bankruptcy plan on hold". SCOTUSblog. 2023-08-10. Retrieved 2023-08-11.

- ^ Totenberg, Nina (December 4, 2023). "Purdue Pharma, Sacklers' OxyContin settlement lands at the Supreme Court". NPR. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ a b c "In re: Purdue Pharma L.P., No. 22-110 (2d Cir. 2023)". Justia Law. Retrieved 2023-08-11.

- ^ Mann, Brian (October 21, 2020). "Purdue Pharma Reaches $8B Opioid Deal With Justice Department Over OxyContin Sales". NPR. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ Bebinger, Martha (September 28, 2021). "The Purdue Pharma Deal Would Deliver Billions, But Individual Payouts Will Be Small". NPR. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ Hafen, Nick (December 4, 2023). "Purdue Pharma's Bankruptcy Case, Explained". The Dispatch. Retrieved August 8, 2024.

- ^ "Purdue Pharma and the Sackler family reach $6 billion OxyContin settlement : NPR". npr.org. Retrieved 2024-06-29.

- ^ "Harrington v. Purdue Pharma (In re Purdue Pharma ), 21 cv 7969 (CM) | Casetext Search + Citator". casetext.com. Retrieved 2023-09-10.

- ^ Ochsner, Evan (November 29, 2023). "Purdue Confronts Supreme Court Skeptical of Bankruptcy Power". Bloomberg Law. Retrieved August 8, 2024.

- ^ Quinn, Melissa (December 4, 2023). "Purdue Pharma bankruptcy plan that shields Sackler family faces Supreme Court arguments". CBS News. Retrieved August 8, 2024.

- ^ Laise, Eleanor (December 1, 2023). "Supreme Court set to hear Purdue Pharma case that could shake up opioid settlement — and the bankruptcy process". Market Watch. Retrieved August 8, 2024.

- ^ Hurley, Lawrence (August 10, 2023). "Supreme Court puts Purdue Pharma bankruptcy deal on hold". NBC News. Retrieved August 8, 2024.

- ^ Martin, Craig; Ehrlich Albanese, Rachel. "Limiting chapter 11 as a tool for collective resolution of mass tort liabilities". DLA Piper. Retrieved August 8, 2024.

- ^ Cole, Devan; de Vogue, Ariane (2023-08-10). "Supreme Court blocks $6 billion opioid settlement that would have given the Sackler family immunity | CNN Politics". CNN. Retrieved 2023-08-11.

- ^ Stohr, Greg (August 10, 2023). "Supreme Court Halts Purdue's Opioid Pact, Will Hear Appeal (2)". Bloomberg Law. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "HARRINGTON, WILLIAM K. V. PURDUE PHARMA, L.P., ET AL. (CERTIORARI GRANTED)" (PDF). Supreme Court of the United States.

- ^ "The Supreme Court is torn over Purdue Pharma's opioid settlement". The Economist. December 5, 2023. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ a b c Howe, Amy (December 4, 2023). "Court conflicted over Purdue Pharma bankruptcy plan that shields Sacklers from liability". SCOTUSblog. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ Dwyer, Devan (December 4, 2023). "Supreme Court wrestles with Purdue Pharma settlement and legal shield for Sackler family". ABC News. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ a b Gumport, Leonard. "SUPREME COURT HEARS ORAL ARGUMENT IN PURDUE PHARMA CASE". California Lawyers Association. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ Quinn, Melissa (December 4, 2023). "Supreme Court wrestles with legal shield for Sackler family in Purdue Pharma bankruptcy plan". CBS News. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ Fritze, John (December 4, 2023). "Supreme Court split on whether the Sackler family can be sued over opioid crisis". USA Today. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ Barnes, Robert; Ovalle, David (December 4, 2023). "Supreme Court appears torn during Purdue opioid settlement arguments". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ Fritze, John; Cole, Devan (June 27, 2024). "Supreme Court rejects multibillion-dollar Purdue Pharma opioid settlement that shielded Sackler family". CNN. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ Sherman, Mark (June 27, 2024). "The Supreme Court rejects a nationwide opioid settlement with OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma". The Associated Press. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ VanSickle, Abbie (June 27, 2024). "Supreme Court Jeopardizes Opioid Deal, Rejecting Protections for Sacklers". The New York Times. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ Ovalle, David; Jouvenal, Justin (June 27, 2024). "Supreme Court blocks controversial Purdue Pharma opioid settlement". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c Kanute, Nathan (July 18, 2024). "SCOTUS Decides Against Sacklers' Release in Purdue Pharma". Snell & Wilmer. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Howe, Amy (June 27, 2024). "Supreme Court blocks OxyContin bankruptcy plan". SCOTUSblog. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Harrington v. Purdue Pharma L.P. and the Future of Nonconsensual Third-Party Releases in Bankruptcy". O'Melveny & Myers. July 2, 2024. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c Harrell, Alex; Taticchi, Mark (June 27, 2024). "Supreme Court Decides Harrington v. Purdue Pharma L.P." Faegre Drinker. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ Mole, Beth (June 17, 2024). "SCOTUS tears down Sacklers' immunity, blowing up opioid settlement". Ars Technica. Retrieved June 28, 2024.

- ^ McGreal, Michelle; Fung, Katherine; Deutsch, Douglas (July 10, 2024). "Purdue Pharma Bankruptcy Ruling Sidesteps Chapter 15 Implications". Bloomberg Law. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ Mann, Brian; Totenberg, Nina (June 27, 2024). "Supreme Court rejects controversial Purdue Pharma bankruptcy deal". NPR. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ "Purdue Pharma and the Supreme Court". The Wall Street Journal. June 28, 2024. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ Janson, Bart; Groppe, Maureen (June 27, 2024). "Supreme Court throws out multi-billion dollar settlement with Purdue over opioid crisis". USA Today. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ Quinn, Melissa (June 27, 2024). "Supreme Court rejects Purdue Pharma bankruptcy plan that shielded Sackler family". CBS News. Retrieved July 29, 2024.