Green pigments

Green pigments are the materials used to create the green colors seen in painting and the other arts. At one time, such pigments came from minerals, particularly those containing compounds of copper. Green pigments reflect the green portions of the spectrum of visible light, and absorb the others. Important green pigments in art history include Malachite and Verdigris, found in tomb paintings in Ancient Egypt, and the Green earth pigments popular in the Middle Ages.[1] More recent greens, such as Cobalt Green, are largely synthetic, made in laboratories and factories. Today, the main green pigment is Phthalocyanine Green G.

Phthalocyanine green

[edit]

The dominant green pigment is Phthalocyanine Green G, which is sold under many commercial names. It is a synthetic green pigment from the group of phthalocyanines, a complex of copper(II) with chlorinated phthalocyanine. It is a soft green powder, which is insoluble in water.[2] It is a bright, high intensity colour used in oil and acrylic based artist's paints, and in other applications.

Chrome oxide and viridian

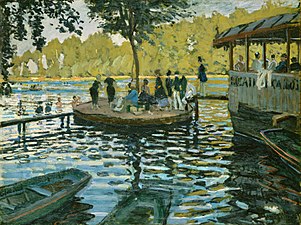

[edit]Chromium(III) oxide (or chromia) is one of the principal oxides of the element chromium. It is the dominant green pigment in industry, with an annual production of 28,000 tons in 1996.[3] Viridian is a blue-green synthetic pigment of medium saturation and relatively dark in value, created in the 19th century. It takes its name from "Viridis", the Latin word for green.[4] It became a particular favourite of the painters Paul Cézanne, Jean Renoir and Claude Monet.

-

Chomium(III)-oxide sample

-

La Grenouillére

Claude Monet (1869) -

Mountains in Provence

Paul Cézanne (c. 1890-92)

Minor or former green pigments

[edit]Verdigris

[edit]Verdigris or Vert-de-Gris, is a blue-green, copper-based pigment. Its name comes from the natural pigments that form a patina on copper, bronze, and brass as it ages.[5] Oneexample is the green patina that formed on the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor. In the Middle Ages, the patina was made by attaching copper strips to a wooden block with acetic acid, then burying the sealed block in dung. It would be dug up a few weeks later, the verdigris scraped off. Another method was to put copper plates in clay pots filled with distilled wine. The verdigris which formed was scraped off each week.[6]

In the 19th century and earlier, the pigment was also made by hanging copper plates over hot vinegar in a sealed pot until a green crust formed on the copper.[6] Today it is usually made by treating Copper(II) hydroxide with acetic acid.[7]

The pigment was used by the Romans, particularly in the murals at Pompeii.[8] The pigment had its weaknesses; it sometimes suffered from humidity and heat, and when mixed with other colors, sometimes altered them. Verdigris was particularly unstable when used to color an oil paint. It was sometimes mixed with lead white, giving it better opacity. Leonardo da Vinci, in his Treatise on Painting, advised artists to avoid it. Nonetheless, it was widely used in miniature painting, in Safavid art and the art of Mongolia. In the late 19th century, it was almost entirely replaced by the synthetic Chrome green.[9]

Paolo Veronese used verdigris with lead white and some yellow in The Adoration of the Magi, at the National Gallery in London. The color has largely retained its particular brilliance.[10]

-

Statue of Liberty, with verdigris patina

-

Verdigris pigment

-

Nativity Mistica

Botticelli (1500).

The verdigris green glaze of the angels' costumes, painted over gold leaf, has degraded and darkened with time. -

Adoration of the Magi

Veronese (1573). Verdigris with lead white

Malachite

[edit]Large deposits of malachite were mined by the Egyptians in the eastern desert and the west of Sinai. [11] Cleopatra is recorded to have used malachite to color her eyelids. It was mixed with egg or with the sap of the acacia plant, and used to paint papyrus manuscripts and the walls of tombs.[12]

It was also widely used in China from antiquity, first in painting landscapes, and then, from the 5th century BC until the 3rd century AD, to make green inks, when the official palette of colors, under the influence of Confucianism, was reduced to blues made with azurite, and greens made with malachite.[13]

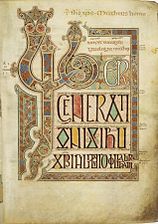

Artists in India imported malachite from Turkestan for murals, and monks in Tibet ground it coarsely to preserve the intensity of the color in manuscripts. In Europe, and particularly in Ireland, it was widely used for intense greens in illumination and miniature painting. They avoided mixing it with other colors, because in a mixture it became unstable.[14]

It was (and is) extremely expensive (more than 100 Euros for 100 grams in 2000),[citation needed] so it was usually only used on limited surfaces. It was largely replaced in the early 19th century by chrome green, though it is still frequently used in China for fine greens. A synthetic form of malachite, verditer, has also been used.

In Latin America, the Teotihuacan civilisation, which ruled in Mexico between 300 and 650, AD, made murals using crushed malachite, which was mixed with chalk for lighter shades, or mixed with blue from azurite or lapis-lazuli to make blue greens, or with yellow ochre to make yellow-greens.[15]

Classical painters made extensive use of the color. The wedding gown in the Arnolfini Portrait, by Jan van Eyck (1434), was painted with malachite.[16]

-

Arnolfini Portrait

Jan van Eyck, (1434)

(National Gallery, London)

Green earth (Terre Verte)

[edit]Green earth was an olive-green natural pigment widely used in the 14th and 15th centuries. It was often used in Italian painting as an under layer beneath flesh colors, particularly in painting by Duccio. In some of Ducco's paintings the upper flesh colors deteriorated, and the green under layer has become visible. Green earth pigments in the Middle Ages supplemented the more expensive malachite pigment. In Europe, they came from Verona, the South of France, and Cyprus. During the Roman Empire they were widely used in frescoes decorating villas. They were used either pure or mixed with other pigments, such as Egyptian Blue. They also were used Egypt in portraits at Fayoum, and in the Buddhist temples at Ajanta in India. In the Middle Ages, since the color by itself was somber, it was sometimes brightened with lead white.

They were also used by Native American artists in North America, particularly the Hopis, who used them to color their ceremonial sand paintings.[17]

-

Green earth pigment

-

Murals in the Ajanta Caves in India (5th century)

-

Mural of Tawa, the symbol of the Sun, from the Hopi tribe, Painted Desert Inn, Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona

Emerald Green

[edit]Emerald Green, also known as Paris Green, Scheele's Green, Schweinfurt green and Vienna Green, is a synthetic inorganic compound, made by a reaction of sodium arsenite with copper(II) acetate. While it makes a beautiful rich green, the color of the emerald stone, it is highly toxic, due to a main ingredient, arsenic.[18] It was invented as 'emerald green' in 1814 by two chemists, Russ and Sattler, at the Wilhelm Dye and White Lead Company of Schweinfurt, Bavaria, who were trying to improve another similar synthetic pigment, Scheele's green, so that it would not darken around sulfides. Because of its toxic arsenic content, it became a popular rodenticide and insecticide,[19]

Emerald green was particularly popular with the Impressionists, including Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh, both of whom in 1888 placed vivid reds next to Emerald green to create jarring contrasts in their paintings Arlésiennes (Mistral) and The Night Cafe. Van Gogh wrote of the Night Cafe: "The café is one of the most horrible I have every painted. But was intentional, because I tried to express the terrible passions of humanity by means of the red and green".[20]

-

Emerald green pigment

-

Arlesiennes (Mistral)

Paul Gauguin (1888) -

The Night Café

Vincent van Gogh (1888)

Chemical composition of natural and synthetic non-organic green pigments

[edit]- Cadmium green: mixture of cadmium yellow (CdS) and chrome green (Cr2O3).

- Chrome green (PG17): anhydrous chromium(III) oxide (Cr2O3).

- Viridian (PG18): hydrated chromium(III) oxide Cr2O3 • xH2O.

- Cobalt green: (CoZnO2).

- Malachite: cupric carbonate hydroxide (Cu2CO3(OH)2).

- Scheele's Green (also called Schloss green): cupric arsenite (CuHAsO3).

- Green earth: also known as terre verte and Verona green (K[(Al,Fe3+),(Fe2+,Mg](AlSi3,Si4)O10(OH)2).

Notes and citations

[edit]- ^ Varichon (2005), pp. 205-211

- ^ Löbbert, Gerd (2000). "Phthalocyanines". Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a20_213. ISBN 3527306730..

- ^ Buxbaum, Gunter; Printzen, Helmut; Mansmann, Manfred; Räde, Dieter; Trenczek, Gerhard; Wilhelm, Volker; Schwarz, Stefanie; Wienand, Henning; Adel, Jörg; Adrian, Gerhard; Brandt, Karl; Cork, William B.; Winkeler, Heinrich; Mayer, Wielfried; Schneider, Klaus (2009). "Pigments, Inorganic, 3. Colored Pigments". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.n20_n02. ISBN 978-3-527-30385-4.

- ^ Maerz and Paul (1930), A Dictionary of Color. McGraw-Hill, New York. Page 18 See: "Table--Polyglot Table of Principle Color Names" Pages 18-19

- ^ "Verdigris" Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ a b Darnton, Robert. "A Bourgeois Puts His World in Order" in The Great Cat Massacre --and other Episodes in French Cultural History. New York: Vintage Books, 1985. p. 114.

- ^ Solomon, Sally D.; Rutkowsky, Susan A.; Mahon, Megan L.; Halpern, Erica M. (2011). "Synthesis of Copper Pigments, Malachite and Verdigris: Making Tempera Paint". Journal of Chemical Education. 88 (12): 1694–1697. doi:10.1021/ed200096e.

- ^ Varichon (2005), pp. 214-215

- ^ Bomford and Roy, "A Closer Look at Colour" (2009), p. 38-39

- ^ Charanay and De Givry, Comment Regarder Les Couleurs Dans la Peinture, (2017), p. 97

- ^ Gettens, R.J. and Fitzhugh, E. W. (1993) "Malachite and Green Verditer", pp. 183–202 in Artists’ Pigments. A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, Vol. 2: A. Roy (Ed.) Oxford University Press. ISBN 0894682601

- ^ Varichon (2005), p. 212

- ^ Varichon (2005), p. 212

- ^ Varichon (2005) p. 212-213

- ^ Varichon (2005), pg. 198

- ^ Varichon, Couleurs- Pigments et Teintures dans les mains des Peuples, p. 213

- ^ Varichon, Anne, Couleurs - Pigments et Teintures dans les Mains des Peuples, (2000), p. 210-211

- ^ "Hazardous Substance Fact Sheet" (PDF). NJ Dept. of Health and Senior Services. Retrieved 2011-02-07.

- ^ "Dangers in the Manufacture of Paris Green and Scheele's Green". Monthly Review of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 5 (2): 78–83. 1917. JSTOR 41829377.

- ^ Ball, Philip, "Histoire Vinvante des Couleurs" (2005), p. 353-353

Bibliography

[edit]- Pastoureau, Michel (2013). Vert: Histoire d'une couleur (in French). Paris: Éditions du Seuil. ISBN 978-2-7578-6731-0.

- Varichon, Anne (2005). Couleurs: pigments et teintures dans les mains des peuples (in French). Paris: Editions du Seuil. ISBN 978-2-02-084697-4.

- Bomford, David; Roy, Ashok (2009). A Closer Look - Colour. London: National Gallery. ISBN 978-185709-442-8.