Gortyna

Gortyna /ɡɔːrˈtaɪnə/ (Ancient Greek: Γόρτυνα; also known as Gortyn (Γορτύν)) was a town of ancient Crete which appears in the Homeric poems under the form of Γορτύν;[1][2] but afterwards became usually Gortyna (Γόρτυνα). According to Stephanus of Byzantium it was originally called Larissa (Λάρισσα) and Cremnia or Kremnia (Κρήμνια).[3]

History

[edit]This important city was next to Knossos in importance and splendour; in early times[when?] these two great towns had entered into a league which enabled them to reduce the whole of Crete under their power; in after-times[when?] when dissensions arose among them they were engaged in continual hostilities.[4] It was originally[when?] of very considerable size, since Strabo reckons its circuit at 50 stadia (about 9 km (6 mi), implying an area of about 6.4 km2 (1,600 acres)); but when he wrote it was very much diminished.[4] He adds that Ptolemy Philopator had begun to enclose it with fresh walls; but the work was not carried on for more than 8 stadia (about 1.5 km (1 mi)).[4] In the Peloponnesian War, Gortyna seems to have had relations with Athens.[5] In 201 BC, Philopoemen, who had been invited over by the inhabitants, assumed the command of the forces of Gortyna.[6] In 197 BC, five hundred of the Gortynians, under their commander, Cydas, which seems to have been a common name at Gortyna, joined Quinctius Flamininus in Thessaly.[7]

Gortyna stood on a plain watered by the river Lethaeus, and at a distance of 90 stadia (about 16 km (10 mi)) from the Libyan Sea, on which were situated its two harbours, Lebena and Metallum,[4] and is mentioned by numerous ancient writers — Pliny the Elder,[8] the author of the Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax, Ptolemy,[9] and Hierocles, who commenced his tour of the island with this place.[10] In the neighbourhood of Gortyna, the fountain of Sauros is said to have been surrounded by poplars which bore fruits;[11] and on the banks of the Lethaeus was another famous spring, which the naturalists said was shaded by a plane-tree, which retained its foliage through the winter, and which the people believed to have covered the marriage-bed of Europa and the metamorphosed Zeus.[12]

The site of Gortyna is at modern Gortyn, where extensive ruins of the ancient town remain.[13][14] It is a major archaeological site in Crete.

Archaeology

[edit]Excavations of Gortyn were begun in 1884 by the Italian School of Archaeology at Athens. The excavations showed that Gortyn was inhabited from the Neolithic age. Ruins of a settlement on the citadel of Gortyn, were discovered and dated back to 1050 BC, their collapse dating to the seventh century BC. Later the area was fortified with a wall. At the top of the hill in the citadel a temple was found dating to the 7th century BC. In this area two embossed plates were found, along with several other sculptures and paintings. Daedalic plastic and many other clay figurines, black-figure and red-figure pottery, especially the type called kernos, were found in the temple. Graves dating to the Geometric age were found on the south side of the citadel. Regarding the lower town, the excavation uncovered the position of the agora (market) and the temple of Pythian Apollo, which is 600 meters from the agora. At the foot of Prophet Elias are traces of a sanctuary of Demeter.

Monuments

[edit]

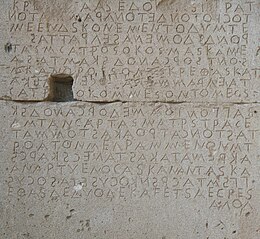

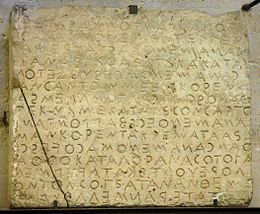

The heart of Roman Gortyn is the Praetorium, the seat of the Roman Governor of Crete. The Praetorium was built in the 1st century AD, but it was altered significantly over the next eight centuries. In the same area, between the Agora and the temple of Apollo are the ruins of the Roman baths (thermae), as well as the temple of Apollo, an honorary arch, and the temple of the Egyptian deities with the worship statues of Isis, Serapis, and Anubis. Parts of the Roman settlement, such as the theater (2nd century AD), have been unearthed during excavations. The theater has two entrances and a half-circular orchestra, the outline of which may still be seen today. Behind the Roman Theater are what has been called the "Queen of the Inscriptions". These inscriptions are the laws of the city of Gortyn, which are inscribed in the Dorian dialect on large stone slabs and are still plainly visible.

Law code

[edit]

Among archaeologists, ancient historians, and classicists Gortyn is known today primarily because of the 1884 discovery of the Gortyn code, which is both the oldest and most complete known example of a code of ancient Greek law.[15][16] The code was discovered on the site of a structure built by the Roman emperor Trajan, the Odeon, which for the second time, reused stones from an inscription-bearing wall that also had been incorporated into the foundation of an earlier Hellenistic structure. Although portions of the inscriptions have been placed in museums such as the Louvre in Paris, a modern structure at the site of the mostly ruined Odeon now houses many of the stones bearing the famous law code."

A copy of the code has been returned to Athens by the Italian Museum in Taranto and is now housed in the Greek Vouli. The curator of the Taranto Museum spoke in Greek and told the famous and political guests that, "Greece is not part of Europe, it is Europe."

Myth of Europa and Zeus

[edit]Classical Greek mythology has it that Gortyn was the site of one of Zeus' many affairs. This myth features the princess Europa, whose name has been applied to the continent, Europe. Disguised as a bull, Zeus abducted Europa from Phoenicia and they had an affair under a plane tree (platanus),[17] a tree that may be seen today in Gortys. Following this affair three children were born, Minos, Rhadamanthys and Sarpedon, who became the kings of the three Minoan Palaces in Crete. The identification of Europa in this myth gives weight to the claim that the civilization of the European continent was born on the island of Crete. A colossal statue of Europa sitting on the back of a bull was discovered at the amphitheatre in Gortyna in the nineteenth century and is now in the collections of the British Museum.[18] Many coins were found with Europa representations on the back, showing that the people honored Europa as a great goddess.[19]

The Odyssey

[edit]According to Book III of Homer's Odyssey, Menelaus and his fleet of ships, returning home from the Trojan War, were blown off course to the Gortyn coastline. Homer describes stormy seas that pushed the ships against a sharp reef, ultimately destroying many of the vessels but sparing the crew.

Notable people

[edit]- Thaletas[20] (7th century BC), musician

- Saint Titus (d. 107), Bishop of Crete and saint

- Philip of Gortyna (d. 180), Bishop of Gortyn and saint

References

[edit]- ^ Homer. Iliad. Vol. 2.646.

- ^ Homer. Odyssey. Vol. 3.294.

- ^ Stephanus of Byzantium. Ethnica. Vol. s.v. Γόρτυνα.

- ^ a b c d Strabo. Geographica. Vol. x. p.478. Page numbers refer to those of Isaac Casaubon's edition.

- ^ Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War. Vol. 2.85.

- ^ Plutarch Phil. 13.

- ^ Livy. Ab urbe condita Libri [History of Rome]. Vol. 33.3.

- ^ Pliny. Naturalis Historia. Vol. 4.20.

- ^ Ptolemy. The Geography. Vol. 3.17.10.

- ^ Hierocles. Synecdemus.

- ^ Theophrast. H. P. 3.5.

- ^ Theophrast. H. P. 1.15; Varr. de Re Rustic. 1.7; Pliny. Naturalis Historia. Vol. 12.1.

- ^ Richard Talbert, ed. (2000). Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. Princeton University Press. p. 60, and directory notes accompanying. ISBN 978-0-691-03169-9.

- ^ Lund University. Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire.

- ^ Ι.Α. Typaldos - Interpretation of the Gortyn inscription discovered at 1884 (Athens 1887)

- ^ Marg. Guarducci, Gortyniarum legum titulus maximus (page 123, 4th book - Inscriptiones creticae)

- ^ Yves Bonnefoy, Greek and Egyptian Mythologies (1992) University of Chicago Press

- ^ British Museum Collection

- ^ In general cf. Davaras, Costis (2001). Führer zu den Altertümern Kretas, Athens, pp. 201–205.

- ^ Επίτομο Γεωγραφικό Λεξικό της Ελλάδος (Geographical Dictionary of Greece), Μιχαήλ Σταματελάτος, Φωτεινή Βάμβα-Σταματελάτου, εκδ. Ερμής, ΑΘήνα 2001