Good Tsar, bad Boyars

"Good Tsar, bad Boyars" (Russian: Царь хороший, бояре плохие, romanized: Tsar khorosiy, boyarie plokhiye), sometimes also known as Naïve Monarchism, is a Russian political phenomenon in which positive actions taken by the Russian government are viewed as being the result of the leader of Russia, while negative actions taken by the government are viewed as being caused by lower-level bureaucrats unbeknownst to the leader. Originating from the Russian Empire, the term has since been used to refer to the leaders of the Soviet Union and post-Soviet Russian Federation, particularly during the rule of Vladimir Putin.

Development

[edit]The concept that would later become known as "Good Tsar, bad Boyars" originates from the Russian Empire. As part of the divine right of kings, the image of a kind and caring Tsar was deliberately cultivated by Russian authorities. This was assisted by the disparate nature of Russia, as much of the population was located in rural areas far from the Russian capital. By contrast, Boyars, members of the aristocracy who served bureaucratic functions, were located closer to the peasantry and thus more tangible to the broader population. As a result, popular dissent was directed primarily at Boyars, rather than the Tsar.[1]

History

[edit]Russian Empire

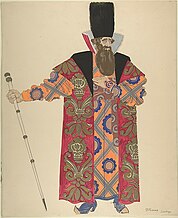

[edit]During the Russian Empire, the concept of "Good Tsar, bad Boyars" was practiced by several Russian tsars, including Ivan the Terrible and Peter the Great. Symbolic actions were taken to reinforce this view, such as the public humiliations or executions of members of the nobility and bureaucracy.[2]

The phenomenon was put to a serious test during the rule of Nicholas II, beginning with the Khodynka Tragedy, a stampede that occurred during his coronation. Undermined by continued instability in the Empire, the belief that the bureaucracy was to blame for the disasters was seriously damaged as a result of the 1905 Bloody Sunday protests. During the protests, a group led by Father Georgy Gapon marched on the Winter Palace in an effort to provide evidence of bureaucrats' misdeeds to the Emperor. The protesters were subsequently fired upon by members of the Russian Imperial Guard, leading to mass casualties and the beginning of widespread, violent protests aiming to overthrow the government. Following Bloody Sunday, support for Nicholas II seriously declined and eventually led to the Russian Revolution that toppled the monarchy.[3]

Soviet Union

[edit]The concept of naïve monarchism was revived following the Russian Revolution, and was applied to Soviet leader Joseph Stalin during the Great Purge.[4] Individuals who had fallen victim to the purges frequently wrote letters to Stalin, believing that he would correct the error upon being informed of the miscarriage of justice.[2] The concept was later applied by Leonid Brezhnev, who sought to be memorialised in such a fashion.[5]

The phenomenon was also found in the Soviet government's treatment of previous leaders; the phrase "Good Tsar, bad Boyars" was used by Russian writer Viktor Nekrasov in an analysis of Sergei Eisenstein's 1944 film Ivan the Terrible.[6]

Russian Federation

[edit]Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the image of a good Tsar and bad Boyars has been applied to Russian President Vladimir Putin, and forms an important part of his public image. Putin has deliberately established the image of himself as a "good Tsar", including via publicly humiliating local officials and demonstrating his ability to bypass local bureaucracy in solving local problems.[7] Swedish Institute of International Affairs research fellow Natalia Mamontova, in her studies of the phenomenon, has argued that the majority of Russians no longer completely believe in the concept, but publicly express their belief in it either out of fear of being targeted by the government or in order to increase pressure on local officials.[8]

The concept gained renewed attention following the 2023 Wagner Group rebellion, when Wagner Group commander Yevgeny Prigozhin marched towards the Russian capital of Moscow. Prigozhin's comments that Putin had been manipulated into invading Ukraine by generals and oligarchs were interpreted by some sources, such as Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty correspondent Steve Gutterman, as reflecting sentiments of naïve monarchism.[9]

Outside Russia

[edit]Besides Russia, the phenomenon has been applied by leaders in other post-Soviet states, and the term has occasionally been used as a pejorative phrase. A 2015 study by the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs found that the concept also exists in Azerbaijan, where Ilham Aliyev is largely popular despite the unpopularity of other government institutions.[1] In Ukraine, the phrase has been used in a negative to refer to politicians' efforts to shield themselves from blame for controversial political actions by casting other, lower-ranking politicians as responsible. Such an accusation has been described in reference to Petro Poroshenko[10] and Volodymyr Zelenskyy,[11][unreliable source?] both presidents of Ukraine.

In World War 2 Germany, a similar saying circulated: If the Führer knew. People widely believed that incompetent and/or malevolent bureaucrats would withhold important information from Adolf Hitler. If Hitler learned about suffering and shortcomings, so the people believed, he would swiftly issue orders to rectify the problem. As in Good Tsar, bad Boyars, pleas for help were directed at the Führer in Berlin, while criticism was leveled at the lower level bureaucrats and officers.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Goble, Paul (18 February 2015). "'Good Tsar, Bad Boyars': Popular Attitudes and Azerbaijan's Future". Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ a b "Good Tsar / Dobryy Tsar". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ Guzvica, Stefan (18 May 2022). "Peasant Letters to the Tsar: A Forgotten Russian Tradition". The Collector. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ Radzikhovsky, Leonid (10 December 2022). "Почему Сталин поставил Фадеева руководителем советских писателей" [Why Stalin placed Fadeyev as head of the Soviet Writers]. Rossiyskaya Gazeta. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ Zamostyanov, Arseny (9 November 2012). ""Добрый царь"" ["Good Tsar"]. Century (in Russian). Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ Nekrasov, Viktor (16 November 1983). "«Иван Грозный» С. Эйзенштейна" [S. Eisenstein's "Ivan the Terrible"]. Viktor Nekrasov Writer's Memorial Website. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ Weir, Fred (1 July 2019). "Putin flexes as 'good czar,' but can he remake Russia?". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ Mamontova, Natalia (23 April 2018). "Vladimir Putin – a tsar without loyal subjects?". Swedish Institute of International Affairs. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ Gutterman, Steve (24 June 2023). "Prigozhin's 'Mutiny' And The Challenge To Putin". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ "Poroshenko plays "good tsar, bad boyars" - MP". LB.ua. 4 October 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ Serdiuk, Vladyslav (15 October 2020). ""Царь хороший, бояре плохие". Зачем Зеленскому понадобился опрос на выборах" ["Good Tsar, bad Boyars": Why Zelenskyy needed an election survey]. LIGA.net (in Russian). Retrieved 17 January 2024.