Gender and webcomics

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (August 2021) |

In contrast with mainstream American comics, webcomics are primarily written and drawn by women and gender variant people. Because of the self-published nature of webcomics, the internet has become a successful platform for social commentary, as well as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) expression.

Statistics

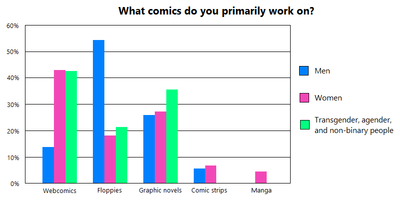

[edit]A 2015 study by David Harper concluded that webcomics were vastly more popular format to female, transgender, and non-binary comic artists than for men. More than 40% of the women, transgender, and non-binary comic artists reported to work primarily in webcomics in this study, while only 15% of men did. Harper suggested that this may be because the self-published nature of webcomics form a lower barrier to entry, while traditional mediums such as comic books are gatekept by cisgender men, though he also suggested that this disparity may just be a difference in interest between the groups.[2]

According to a study by Erik Melander in 2005, at least 25% of webcomic creators were female. This percentage was significantly larger than the number of successful women creating print comics at the time, and the number may have been even higher, as a certain percentage of contributors were unknown.[3] In 2015, 63% of the top 30 comic creators on webcomic conglomerate Tapastic were female.[4] In 2016, 42% of the webcomic creators on WEBTOON were female, as was 50% of its 6 million active daily readers.[5][6]

Women in webcomics

[edit]

Girls with Slingshots creator Danielle Corsetto stated that webcomics are probably a female-dominated field because there is no need to go through an established publisher. ND Stevenson, creator of Nimona and Lumberjanes, noticed that webcomics predominantly feature female protagonists, possibly to "balance out" the content of mainstream media. Corsetto noted that she has never encountered sexism during her career, though Stevenson described some negative experiences with Reddit and 4Chan, websites outside of their usual channels.[8]

Oliver Sava of The A.V. Club pointed out in 2016 that there exists a growing community of black women cartoonists creating webcomics.[9]

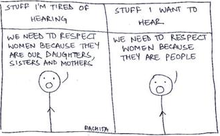

In India, where rape of women has been a big issue in the 2010s, Indian webcomics formed a platform for artists to poke fun at patriarchy, feminism, and various other gender-related topics. According to human rights activist and webcomic creator Rachita Taneja, humor aids in communicating complex subjects to large groups of people, and the inclusiveness of webcomics makes it an excellent medium for said communication.[7][10]

Girlamatic was a subscriber-based webcomic site founded by Joey Manley in 2003. The website's purpose was to syndicate webcomics created primarily by women and marketed primarily to women. Girlamatic included webcomics created by various well-known female webcomic artists, including Shaenon Garrity and Lea Hernandez. The syndicate had won various Lulu awards for being among the "most women-friendly and reader- friendly work in comics."[11] Writing for Comixpedia, Eric Burns voiced his worries that initiatives like Girlamatic section off and divide the webcomic community, making it less likely for male readers to come across the works of female webcartoonists.[12]

LGBT in webcomics

[edit]

There exist a large amount of openly gay and lesbian comic creators that self-publish their work on the internet. These include amateur works, as well as more "mainstream" works, such as Kyle's Bed & Breakfast.[13] According to Andrew Wheeler from ComicsAlliance, webcomics "provide a platform to so many queer voices that might otherwise go undiscovered,"[14] and Tash Wolfe of The Mary Sue has a similar outlook on transgender artists and themes.[15]

For some transgender creators, webcomics can also double as autobiographies or autobiografiction. Some of these webcomics are written and illustrated by transgender individuals, accurately depicting their thoughts and reality.[16] An example of such would be Rooster Tails.

Impact

[edit]LGBT representation in webcomics is also thought to be a form of participatory media, since it may "encourage users to contribute voices and resources, such as time and money, toward shared projects".[17] Readers of webcomics primarily containing LGBT topics also have the opportunity to undergo transformative learning.[18]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Harper, David (2015-06-16). "SKTCHD Survey: Is Gender a Determinant for How Much a Comic Artist Earns?". SKTCHD.

- ^ a b Guzdam, de, Jennifer (2015-06-23). "Where's the Money in Comics? This Survey Breaks it Down by Gender". ComicsAlliance. Archived from the original on 2016-01-10.

- ^ Bovri, Bart (2011). 'man, You Split Wood Like a Girl.' Gender Politics In 'y: The Last Man' (Thesis).

- ^ Rosser, Emma (2015-12-17). "A comic book revolution from the man that brought Google to Korea". The Sociable.

- ^ MacDonald, Heidi (2016-02-29). "WEBTOON: readership is 50% female". Comics Beat.

- ^ Johnston, Rich (2016-02-29). "42% Of WEBTOON's Comic Creators Are Female – And Half Are Read By Women". Bleeding Cool.

- ^ a b Sanyal, Pathikrit (2016-03-01). "Stick-figure activism: A clever webcomic that talks about everything that's wrong with our country". IBN Live.

- ^ Campbell, Josie (2013-03-29). "Women in Comics: Stevenson & Corsetto on Webcomics and the Future". Comic Book Resources.

- ^ Sava, Oliver (2016-02-19). "Agents Of The Realm, M.F.K., and the ascent of black women in webcomics". The A.V. Club.

- ^ Choksi, Nidhi (2015-12-13). "A new superhero has emerged, the web comic". Hindustan Times.

- ^ "Lulu Awards". Friends of Lulu. 8 March 2009.

- ^ Burns, Eric (2005-04-17). "Feeding Snarky". Comixpedia. Archived from the original on 2005-04-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Palmer, Joe (2006-10-16). "Gay Comics 101". AfterElton.com. p. 3. Archived from the original on 2007-10-15.

- ^ Wheeler, Andrew (2012-06-29). "Comics Pride: 50 Comics and Characters That Resonate with LGBT Readers". ComicsAlliance. Archived from the original on 2014-03-26.

- ^ Wolfe, Tash (2015-02-23). "Visual Representation: Trans Characters In Webcomics". The Mary Sue.

- ^ Nayek, Debanjana (2016). "(Mis) Representations of The Transgender Identity: the DominantPopular Narrative Culture Versus the Webcomics". Colloquium. 3: 15–20.

- ^ Hatfield, Nami Kitsune (2015). "TRANSforming Spaces: Transgender Webcomics as a Model for Transgender Empowerment and Representation within Library and Archive Spaces". Queer Cats Journal of LGBTQ Studies. 1 (1). doi:10.5070/Q511031151.

- ^ Shin, Kyoung Wan Cathy (2018). Transcending Boundaries with LGBTQ Webtoons: An Alternative Platform for Democratic Discourse (Thesis). ProQuest 2135269046.[page needed]