Gabriel Boughton

Gabriel Boughton | |

|---|---|

| Died | unknown |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | East Indiaman surgeon |

| Medical career | |

| Institutions | East India Company |

Gabriel Boughton was an East India Company (EIC) ship surgeon who travelled to India in the first half of the seventeenth century and became highly regarded by Mughal royalty.

He became the centre of a legend surrounding the acquisition by the EIC of a licence to trade freely in India and establish the first EIC factories on the banks of the Hooghly River in Bengal. According to the legend, incorrectly retold for over a century, Boughton treated and cured emperor Shah Jahan's daughter Jahanara Begum of burns after her clothing caught fire, and in return the emperor granted the EIC a licence to trade freely and to open factories. Boughton was further credited with receiving concessions from the emperor's son Shah Shuja for treating one of the prince's concubines.

After being retold in a number of reputable sources mainly throughout the eighteenth century, EIC expansion in the Indian state of Bengal in the 1840s became attributed to Boughton's story. However, when historians examined its details, some details were found to be impossible due to inconsistencies in dates and the absence of evidence that the emperor's licence ever existed.

Background

[edit]In the early days of the EIC, doctors frequently travelled with traders who were on their way to establish factories. In addition to medical care for themselves and their ships, warehouses, and factories, these "Company ship surgeons" were found to be useful in trading medical treatment for concessions from rich rulers.[1] In India, EIC establishments included Bombay, Surat, Persia, Madras and the east coast, and Bengal and the Bay. Boughton was one of the early medical practitioners of this era, the others including John Woodall, William Hamilton, John Zephaniah Holwell, and William Fullerton.[2]

The English acquired a foothold in India in 1613 by establishing a factory at Surat under the reign of Jahangir and with Portuguese opposition. In 1631, by the order of Shah Jahan, the Portuguese were expelled from Hooghly, and seven years later the emperor appointed his son Shah Shuja to be Viceroy of Bengal. The capital of the province was changed from Gaur to Rajmahal in 1639.[3]

Life

[edit]Boughton entered Surat in 1644 and was appointed to Asalat Khan, the paymaster general of the Mughal empire, who was keen on having the services of a European surgeon. Subsequently, Boughton travelled to Agra. Following the death of Khan in 1647, Boughton was appointed to the emperor’s son, Shah Shuja, then the governor general of Bengal based at Rajmahal. When one of the prince's concubines developed a pain in her side, Boughton was able to cure her and, according to colonial administrator John Beard in 1685, in return received exemption from duty for personal trade but not for the EIC. In 1649, Captain Brookhaven's ship from London arrived in Bengal with duty-free goods "upon the account of Boughton's nishauns",[1] giving the British an advantage over other traders. Two years later, the British returned to establish a factory at Hooghly and obtain another exemption for the EIC. They obtained this by informing Shah Shujah that the previous privileges given by Shah Jahan were for the exemption of all duty.[1]

The legend

[edit]The traditional story differs and first appeared in the second volume of Robert Orme's History of the Military Transactions of the British Nation in Indostan from 1745[1] with a more detailed description in Stewart's book, amongst a number of other publications.[1][4][5] Their primary sources are likely to have been two accounts, one by EIC ship captain Thomas Bowrey and the other by John Beard.[1] It was also reiterated in the article "Surgeon in India: Past and Present", contributed by Dodwell and Miles to the Calcutta Review in 1854 (vol. xxiii).[3]

Appearance in India

[edit]Prior to 1639, as stated in Charles Stewart's 1813 book The History of Bengal, Sir Thomas Roe, who had been sent by James I as ambassador to Jahangir in 1615 and who remained in the Mughal courts for three years, made an entry regarding Boughton in his memoirs,[3] when he wrote that Boughton "had for his dinner three hens, with rice, his drink being water, and a black liquor called cahu [coffee], drank as hot as could be endured".[6] This story was found to be untrue and related to another Boughton.[7] For many years after there is no mention of him until 1636–1637, when he appears stationed in Surat in medical charge of the EIC's ship the Hopewell, as part of the Bombay establishment.[2]

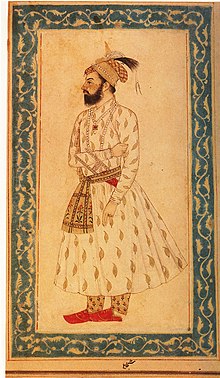

Jahanara Begum's burns

[edit]

In either 1636,[8] 1643, 1644,[7] or 1645,[9] Jahanara Begum, the favourite daughter of Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, was severely burnt when her clothing caught fire in an accident during a dance performance.[1][7] Local healers had failed to cure her, and, at the advice of vizier Assad Khan, the Emperor requested an English surgeon. The council of Surat recommended Boughton, the surgeon of the EIC ship the Hopewell, as best-qualified for attending to the Princess and sent him to the Deccan, where the emperor had his camp. Boughton was successful in healing her and, in return, was asked to name his reward. His request was for the EIC to be granted the privilege and licence of founding factories in Bengal and of trading there freely, without the requirement to pay duty.[3][10][11][12][13]

Sultan Shah Shuja

[edit]

Thereafter, to secure and begin trading, Boughton travelled to Rajmahal, where he became acquainted with the Viceroy of Bengal, Shah Shuja, one of the Emperor's sons, and where further privileges were granted after Boughton healed a lady from the Sultan's zenana.[1][3][7][14] With royal approval, Boughton sent for his EIC men, and subsequently factories were founded at Hooghly, Balasore, and Pipli.[1][3][7]

He was described "with that liberality which distinguishes Britons, sought not for any private emolument, but solicited that his nation might have liberty to trade free of all duties in Bengal and to establish factories in that country",[14] and had therefore been credited with the beginnings of the EIC's trade in Bengal.[15]

Inconsistencies

[edit]An alternative account based on evidence from the historian Firishta is given in Alexander Dow's book The History of Hindostan, from the death of Akbar to the complete settlement of the empire under Aurangzebe (1772).[5][16]

There is enough evidence to show that Boughton pleased his royal patients and had much "influence in high places",[3] important enough that the legend gained popularity and was retold in reputable sources for over a hundred years, gaining its acceptance as true.[1][2] The legend was first scrutinised by historiographer Sir William Foster.[1]

A number of dates have been found to be incompatible. Boughton was not near any royal residence or Agra at the time of Jahanara's injuries.[2] On 3 January 1644, an official letter to the directors of the EIC in London, addressed by its president and council, discloses that Boughton was not sent to Shah Shuja until several years later than the legend tells.[3] Therefore, when further royal concessions were obtained, he was not in Rajmahal as stated in the legend. In addition, Jahanara's burns occurred in 1643–1644, while Boughton's mission to Agra occurred a year later. Her burns had in the meantime been treated and cured by Hakim Anitulla of Lahore. It is also not possible to credit the founding of the factory at Balasore to the further concessions, as it had already been established 12 years before Boughton's visit to Agra.[2] In Stewart's book, he leaves a footnote regarding the concessions given by the emperor, saying "I was not able to find a copy of this firman among the Indian records."[1]

Death

[edit]Gabriel Boughton died in India shortly after the opening of the ports.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Kochhar, Rajesh (September 1999). "The truth behind the legend: European doctors in pre-colonial India". Journal of Biosciences. 24 (3): 259–268. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.623.1442. doi:10.1007/BF02941239. S2CID 23226012. Archived from the original on 17 January 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2019 – via Indian Academy of Sciences.

- ^ a b c d e "The Passing of the I.M.S". The Indian Medical Gazette: 411. July 1947. S2CID 32191279.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "British Medicine in India". British Medical Journal. 1 (2421): 1245–1253. 25 May 1907. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.2421.1245. ISSN 0007-1447. PMC 2357439.

- ^ Charles Stewart (1813). The History of Bengal. Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ a b Beatson, William Burns; Royal College of Physicians of London (1902). Indian Medical Service past and present. London Royal College of Physicians. London : Simpkin and Marshall.

- ^ Kerr, Robert (1824). A General History and Collection of Voyages and Travels (Complete) Arranged in Systematic Order: Forming a Complete History of the Origin and Progress of Navigation, Discovery and Commerce by Sea and Land from the Earliest Ages to the Present Time. Library of Alexandria. ISBN 9781465516121.

- ^ a b c d e Crawford, D. G. (January 1909). "The Legend of Gabriel Boughton". The Indian Medical Gazette. 44 (1): 1–7. ISSN 0019-5863. PMC 5167919. PMID 29005236.

- ^ McDonald, Donald (2 November 1955). "The Indian Medical Service. A Short Account of its Achievements 1600–1947". Section of the History of Medicine. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 49 (1): 13–17. doi:10.1177/003591575604900103. PMC 1889015. PMID 13289828.

- ^ Bhattacherje, S. B. (2009). Encyclopaedia of Indian Events & Dates. New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. pp. A69. ISBN 9788120740747.

- ^ Brown, Andrew Cassels (April 1907). "Two Forgotten Medical Worthies". Edinburgh Medical Journal. 21 (4): 339–351. ISSN 0367-1038. PMC 5280178.

- ^ Hansen, Waldemar (1972). "7. The smell of apples". The Peacock Throne: The Drama of Mogul India. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 127. ISBN 9788120802254.

- ^ Ritchie, Leitch (1848). A History of the Indian Empire and the East Indian Company from the Earliest Times to the Present: Together with Accounts of Beloochistan, Affghanistan, Cashmere ... London: W.H. Allen. p. 103.

- ^ Crooke, William (2017). A New Account of East India and Persia. Being Nine Years' Travels, 1672–1681, by John Fryer. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781317187417.

- ^ a b O'Malley, L. S. S. (1917). "XXI – The roll of honour". Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa Sikkim. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107600645.

- ^ Evan Cotton (1907). Calcutta, Old and New: A Historical & Descriptive Handbook to the City. New York Public Library. W. Newman. pp. 4.

- ^ Dow, Alexander (1772). "The History of Hindostan, from the death of Akbar to the complete settlement of the empire under Aurangzebe". digital.lb-oldenburg.de. Archived from the original on 14 July 2019. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- The English in western India. Anderson, Phillip. Bombay, Smith, Taylor and co. 1854

- The History of Hindostan, from the death of Akbar to the complete settlement of the empire under Aurangzebe, Alexander Dow, T. Beket and P. A De Hondt, London (1772)

- The History Of Bengal, Charles Stewart, Basilisks Press (1813)

- The Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Ed. by James Prinsep, Volumes 2–3, James Prinsep, Calcutta, 1834, p.157

- “Surgeons in India – Past and Present”, Dodwell and Miles Calcutta Review (1854), Vol.XXIII, pp. 241–243